Internal disc disruption

Original Editors - Alexander Chan

Top Contributors - Alexander Chan, Dorien De Strijcker

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Internal disc disruption is a degradation of nucleus pulposus content of intervertebral disc without developing disc herniation, it develops forming radial fissure extend from the nucleus to annulus causing annular tearing and irritation of the free nerve endings if it reaches the outer third of the annulus fibrosis, the radial fissure stimulate chemical and mechanoreceptors causing pain[1]. Repetitive shearing, axial load, and disc compression is believed to be related to the development of fissure, this leads to vertebral endplate fracture where the fissures can develop containing nuclear material of the degraded disc[2]. This could initiate an autoimmune response[3].

IDD was first proposed by Crock (1970), has been defined as lumbar spinal pain, with or without referred pain, stemming from an intervertebral disc, caused by internal disruption of the normal structural and biochemical integrity of the symptomatic disc[4][3].

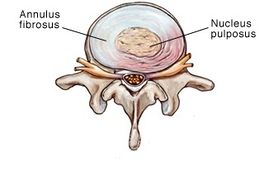

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Click on the link for more specific details about intervertebral disc.

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Internal disc disruption is a subgroup of discogenic pain. Compressive load of the intervertebral disc results in fracture of the vertebral endplate if the fracture doesn't heal it will trigger disc degradation (IDD)

The prevalence of IDD has been estimated to be 39% (95% CI: 29% to 49%) in ninety-two patients with chronic LBP.[5] In a more recent study, it has been estimated at 42% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 35% to 49%).[6]

Classification of IDD[1][edit | edit source]

| Grades | Description[7] |

|---|---|

| grade 1 | Early annular tear extends to the inner third of the disc |

| grade 2 | More annular tear extends to middle third |

| grade 3 | The tear extends to the outer third of the disc |

| grade 4 | The same as grade 3 + circumferential spread in the outer third |

This classification according to the modified Dallas Discograme Scale. Where Grade 0 is the normal disc. Often grade 1, 2 don't associate with pain, and grade 3, 4 presented with pain. [8][9]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The ideal patient symptoms will present with central low back pain without radiation or minimal radiation to one or both limbs describe the pain as it's deep dull aching pain decreases with extension or lying flat. Sitting, driving, twisting, flexion, coughing, and Valsalva maneuver aggravate symptoms[1].

Crock's description of IDD included the following features:

- Low spinal mobility with physical exercise, intractable back pain with pain aggravation

- Leg pain

- Marked weight loss

- Profound depression

- Loss of energy[10]

In the IASP’s Classification of Chronic Pain, IDD has the features of:

- Lumbar spinal pain, with or without referred pain in the lower limb girdle or lower limb;

- Aggravated by movements that stress the symptomatic disk[4]

According to Sehgal (2000), most of the patient’s experience:

- Diffuse, dull ache

- a deep-seated, burning, lancinating pain in the back

- Sensation of a weak, unstable back

- Referral of pain into the hips and lower limbs is not uncommon.

- a varying degree of sitting intolerance

- Lumbar spine movements are slow, guarded and restricted

- History of lifting trauma precedes the back pain in acute cases

- Pain and muscle spasm are less dramatic and more nondescript in persistent cases[11]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Disc herniation:

Extension of disc material near to intervertebral disc space causing a mechanical compression of the nerve root. In which the herniated nucleus pulposus is capable of generating back/leg pain.

Ruptured disc:

Fernston observed that a simple, ruptured disc without herniation can have a clinical presentation similar to herniated nucleus pulposus[12].

Degenerative disc disease:

The intervertebral disc transitions from being asymptomatic to pain generating as a result of degenerative changes. Although altered disc morphology may be asymptomatic, various mechanisms that may give rise to asymptomatic degenerative disc exist.[13][14] IDD is seen to be not dependant on degenerative disc that associated with aging and is most often asymptomatic.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Physical examination alone is insufficient to establish a diagnosis of IDD. Diagnostic imaging, however, has contributed to the understanding of IDD.

- Plain Xrays and Computerized Tomograms (CT) are generally normal.[11]

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the lumbosacral spine can identify areas of high-intensity zone/high signal of the posterior annulus in T2 image, with a loss of signal intensity correlating with abnormal disc morphology on discography.[15][4]

- Provocative discography the gold standard for the diagnosis of lumbar discogenic pain it is a physiologic test that explicitly determines whether a disc is painful. The disc suspected of causing pain is injected with radiolucent dye. The aim is to provoke clinical symptoms and reveal morphological abnormalities in the annulus fibrosis.[3]The test is considered positive if the individual’s concordant pain is reproduced upon stimulating the suspected painful disc, and injection of adjacent discs does not reproduce the typical symptoms.[5] In asymptomatic individuals, discography is not painful, but is frequently painful in those with low back pain. A post-discography CT scan can be used to evaluate the extent of internal disruption within the disc.

Despite the clinical use of discography, its utility has been questioned due to high false positive rates.[3][6][10] It is also associated with procedural risks, is expensive, and can be difficult to access.[11] Discography has also been shown to result in accelerated disc degeneration compared to match-controls.[12]

The criteria for diagnosing IDD from the International Association for the Study of Pain’s Taxonomy Working Group is:[edit | edit source]

1. Lumbar spinal pain, with or without referred pain in the lower limb girdle or lower limb

2. Aggravated by movements that stress the symptomatic disc

3. MRI or CT don't show a visible disc herniation

4. Injection of the disc above or below the suspected disc mustn't elicit pain

5. Diagnostic criteria for lumbar discogenic pain must be satisfied including either:

a) Selective anesthetization of the putatively symptomatic intervertebral disc completely relieves accustomed pain, or save that whatever pain persists can be ascribed to some other coexisting source or cause

b) Provocative discography of the putatively symptomatic disc reproduces the patient’s accustomed pain, but not at least two adjacent discs, and the pain cannot be ascribed to some other source innervated by the same segments as the symptomatic disc

6. CT-discography must demonstrate a grade 3 or greater grade of annular disruption

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Examination[edit | edit source]

It is very difficult to establish a clinical diagnosis only based on history and physical examination when there are no objective clinical findings. There is no clinical test that can make a distinction between IDD patients and patients with other conditions.[5] The only convincing means to establish IDD is provocative discography as described above.

Medical Management [edit | edit source]

1) Pharmacological management

Pharmacological management if for analgesic purposes and may include the use of Acetaminophen (Paracetamol), non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, muscle relaxants, or opioids.[13]

2) Minimally invasive interventional procedures:

- Intradiscal steroid injection

- Radiofrequency denervation

- Intradiscal Electrothermal (IDET) Therapy

3) Surgical treatment:

Internal disc disruption can be managed surgically by fusing the vertebrae at the level of disc disruption.

Disadvantages of surgical fusion include:

- Failure to maintain the height of the intervertebral disc

- Less segmental motion at the fused levels, which may contribute cephalocaudal neuro foraminal stenosis and overloading of adjacent disc levels [11]

Most causes will respond to conservative treatment of medication, relative rest, and physical therapy intervention[16]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

The main goals of treatment are improving function and quality of life, treat pain and in long term, prevent future back injury and disability.

1) Dynamic lumbar stabilisation (core stability):

Traditionally core stability has referred to the active component to the stabilizing system. This includes local muscles that provide segmental stability (eg transversus abdominis, lumbar Multifidus) and/or the global muscles (eg rectus abdominis, erector spinae) that enable trunk movement/torque generation and assistance in the stability in more physically demanding tasks.[14]

2) Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy (McKenzie Method) [15]:

The McKenzie method utilizes the patient’s response to repeated lumbar movements to assess which movements reduce the individual’s most peripheral symptoms. These movements are then combined into an individualized exercise regimen.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Simon J, McAuliffe M, Shamim F, Vuong N, Tahaei A. Discogenic low back pain. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics. 2014 May 1;25(2):305-17.

- ↑ Pezowicz CA, Schechtman H, Robertson PA, Broom ND. Mechanisms of anular failure resulting from excessive intradiscal pressure: a microstructural-micromechanical investigation. Spine. 2006 Dec 1;31(25):2891-903.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Crock, H.V., A reappraisal of intervertebral disc lesions. Med J Aust, 1970. 1(20): p. 983-9.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 IASP Taxonomy Working Group, Classification of Chronic Pain: Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms, 2011.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Schwarzer, A.C., et al., The prevalence and clinical features of internal disc disruption in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1995. 20(17): p. 1878-83.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 DePalma, M.J., J.M. Ketchum, and T. Saullo, What is the source of chronic low back pain and does age play a role? Pain Med, 2011. 12(2): p. 224-33.

- ↑ https://freinlazzara.medicalillustration.com/generateexhibit.php?ID=3102&ExhibitKeywordsRaw=&TL=&A=

- ↑ Aprill C, Bogduk N. High-intensity zone: a diagnostic sign of painful lumbar disc on magnetic resonance imaging. The British journal of radiology. 1992 May;65(773):361-9.

- ↑ Vanharanta H, Sachs BL, Spivey MA, Guyer RD, Hochschuler SH, Rashbaum RF, Johnson RG, Ohnmeiss D, Mooney V. The relationship of pain provocation to lumbar disc deterioration as seen by CT/discography. Spine. 1987 Apr;12(3):295-8.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Crock, H., Internal disc disruption: A challange to disc prolapse fifty years on. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1986. 11(6): p. 650-3.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Sehgal, N. and J.D. Fortin, Internal disc disruption and low back pain. Pain Physician, 2000. 3(2): p. 143-157

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Fernstrom, U., A discographical study of ruptured lumbar intervertebral discs. Acta Chir Scand Suppl, 1960. Suppl 258: p. 1-60.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Roberts, S., et al., Histology and pathology of the human intervertebral disc. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2006. 88 Suppl 2(Supplement 2): p. 10-4.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Bogduk, N., Clinical anatomy of the lumbar spine and sacrum. 4th ed. 2005, New York: Churchill Livingstone.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Milette, P., et al., Differentiating lumbar disc protrusions, disc bulges, and disc with normal contour but abnormal signal intensity. Magnetic resonance imaging with discographic correlations. Spine, 1999. 24(1): p. 44-53.

- ↑ Raj PP. Intervertebral disc: anatomy‐physiology‐pathophysiology‐treatment. Pain Practice. 2008 Jan;8(1):18-44.