Infantile Brachial Plexus Injury

Top Contributors - Robin Tacchetti, Jess Bell and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

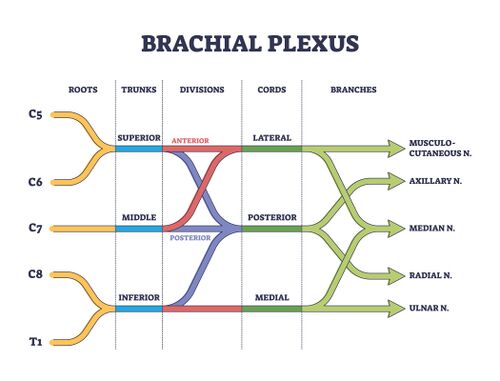

Neonatal brachial plexus palsy (NBPP) is a closed nerve traction injury of the brachial plexus (C5-T1). It predominately occurs during labour and it can limit arm function.[1] [2] [3] NBPP presents with flaccid paralysis or weakness in the upper extremity and is diagnosed soon after birth. The global incidence of NBPP is reported to be between 1-4 cases per 1000 live births with rates varying depending on study setting and availability of foetal and maternal care.[4] The overall incidence of NBPP is decreasing.[2]

Mechanism of Injury[edit | edit source]

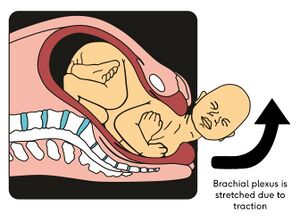

In neonatal brachial plexus injury, obstetric, maternal and infant factors result in the application of traction to the brachial plexus.[2] The most common cause of NBPP is shoulder dystocia - i.e. the "delivery of the anterior shoulder of the baby is hampered by mother’s pubic symphysis".[5] This traction force widens the angle between the baby's shoulder and neck, resulting in an overstretched ipsilateral brachial plexus.[5]

Many infants spontaneously recover or gain close to normal upper extremity function. For those whose motor recovery is incomplete, close monitoring and expert interventions are critically important to optimising outcomes.[4] Prognosis depends on the level of nerve root involvement and the severity of injury.[3] Within the first year of life, 80-96% of individuals with NBPP will recover completely.[5]

Risk factors[edit | edit source]

The risk factors for NBPP include neonatal, materal and labour-related issues.

1. Neonatal

- Large birth weight

- Breech presentation (caesarean section appears as a protective factor)[2]

- Congenital anomalies

2. Maternal

- Age > 35 years

- Cephalopelvic disproportion

- Obesity

- Gestational diabetes mellitus (macrosomia - i.e. babies who are large for their gestational age[6])

- Previous child with NBPP

3. Labour-related factors

- Shoulder dystocia

- Increased duration of second stage of labor (>60 minutes)

- Operative vaginal deliveries

- Vacuum extraction

- Direct compression of the foetal neck during delivery by forceps[5][2][4]

Classification[edit | edit source]

There are several ways to classify NBPP. One classification system is based on which portion of the brachial plexus is injured. The "upper trunk" refers to nerves C5-C6 and is referred to as Duchenne-Erb syndrome. The lower trunk affects nerves C7-T1 and know as Dejerine-Klumpke syndrome. If there is a complete severing of the brachial plexus, then all nerve roots between C5-T1 would be disturbed - this is known as Horner's syndrome.[3]

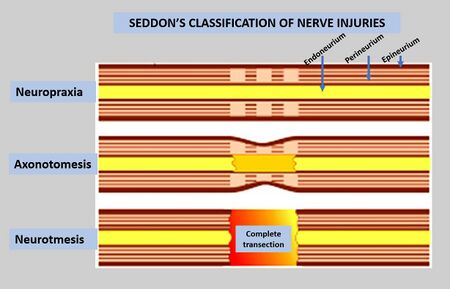

Another classification system is based on the degree of lesion of the nerve. For example:

- neurotmesis: complete tear of the axon and connective tissue with no chance of recovery

- axonotmesis: axon interruption with no, or only partial, interruption to myelin and connective tissue with gradual recovery

- neuropraxic: transient physiological blockage with spontaneous recovery; no nerve rupture with full recovery

- neuroma: blocking of nerve impulse to muscle by injured nerve scar tissue[3][5]

Mallet Classification[edit | edit source]

The Mallet classification system is an assessment tool used with children who have brachial plexus birth injuries. The examination assesses the performance of six upper extremity functional movements. Administrators score the test based on observation of the movement on a scale from V (full function) to I (no function). This test is easy to administer in a clinical setting and has been found to have good internal consistency, inter-observer reliability and intra-observer reliability.[7]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Infantile brachial plexus injury is generally detected by parents or healthcare workers in the immediate neonatal period - they generally observe an absence of motor function in the arm or hand.[3] These motor deficits should be painless. If there is pain during passive range of motion, a fracture should be suspected.[4]

The table below highlights common presentations based on which nerve root is injured:

| Segment Involved | Muscular Deficits | Arm Position |

|---|---|---|

| C5 - deltoid | Abduction of shoulder | Adducted |

| C5 - supra and infraspinatus | External rotation of shoulder | Internally rotated |

| C5 C6 - bracioradialis | Flexion of elbow | Extended |

| C5 C6 - supinators | Supination of forearm | Pronated |

| C6 C7 - extensors of wrist | Wrist extensors | Flexed |

| C6 C7 - extensors of fingers | Finger extensors | Flexed |

NBPP may occur with other conditions including:

- humeral and clavicular fractures

- flexion contracture of the elbow

- progressive glenohumeral dysplasia

- torticollis[4]

Assessment[edit | edit source]

A NBPP assessment should include the following components:

- detailed maternal and delivery history

- musculoskeletal examination

- neurological examination

- active and passive range of motion

- reflex testing: unable to perform Moro reflex and the asymmetrical tonic neck reflex

- respiratory status

- symmetry of chest movements

- determine if there is a need for an x-ray to rule out bony injury[1]

Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Regardless of the type of injury with NBPP, conservative treatment is always initiated as early as possible. Conservative treatment with a multidisciplinary team can include the following interventions:

- passive and active mobilisation exercises

- stretches

- sensory stimulation

- tactile stimulation with varying textures

- brushing and vibration techniques

- bimanual activities

- electrical stimulation to increase muscle strength and inhibit atrophy

- botulinum toxin injections into healthy antagonist muscles

- splints for infants with impaired wrist function to facilitate increased hand function

- constraint induced movement therapy

Therapy should occur several times a week. The family should be involved in the rehabilitation programme and there should be a home programme to achieve the best outcome.[3]

Surgery[edit | edit source]

Children are considered suitable candidates for surgery if they have not shown spontaneous recovery during the first few months of life.[3] Infants with Horner syndrome should have surgery as early as possibly, within 2-3 months of birth if possible.[5]

There are two types of surgery for NBPP: primary and secondary.

- Primary reconstruction: for children who do not have spontaneous recovery within the first three months of life. This type of surgical management may include nerve grafting, nerve transfers, direct repair and/or soft tissue procedures.

- Secondary reconstruction: recommended for children who have had some spontaneous recovery but continue to have significant functional deficit or children who have undergone a primary surgery but continue to have limitation in limb function. Secondary surgery may include osseous procedures and soft tissue reconstructions.[5]

Post surgery, the infant will be placed in a prefabricated cast to limit movement of the neck and affected arm for 1-2 weeks. After 2-3 weeks, gentle range of motion can be initiated. Regular follow-up by a rehabilitation team for a minimum of 5 years is recommended for assessment of recovery and to identify if any secondary reconstructions may be needed to improve function.[5]

** Due to the rate of nerve regeneration (i.e. 1 mm/day or 1 inch/month), clinical changes may not be evident until 1-2 years after surgery. Regular physiotherapy should be provided while waiting for reinnervation to prevent contractures.[5]

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Shah V, Coroneos CJ, Ng E. The evaluation and management of neonatal brachial plexus palsy. Paediatrics & Child Health. 2021 Dec;26(8):493-7.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Van der Looven R, Le Roy L, Tanghe E, Samijn B, Roets E, Pauwels N, Deschepper E, De Muynck M, Vingerhoets G, Van den Broeck C. Risk factors for neonatal brachial plexus palsy: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2020 Jun;62(6):673-83.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Frade F, Gómez-Salgado J, Jacobsohn L, Florindo-Silva F. Rehabilitation of neonatal brachial plexus palsy: integrative literature review. Journal of clinical medicine. 2019 Jul 5;8(7):980.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Heyworth BE, Fabricant PD. BRACHIAL PLEXUS BIRTH PALSY. Rockwood and Matsen's The Shoulder E-Book. 2021 Jun 12:39.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 Meena R, Doddamani RS, Sawarkar DP, Agrawal D. Current Management Strategies in Neonatal Brachial Plexus Palsy. Journal of Peripheral Nerve Surgery Vol. 2021;5(1).

- ↑ Akanmode AM, Mahdy H. Macrosomia. [Updated 2022 Sep 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557577/

- ↑ Russo SA, Topley MT, Richardson RT, Richards JG, Chafetz RS, van Roden EA, Zlotolow DA, Mulcahey MJ, Kozin SH. Assessment of the relationship between Brachial Plexus Profile activity short form scores and modified Mallet scores. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2022 Jan 1;35(1):51-7.