Heterotopic Ossification: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(Undo revision 163405 by Elaine Lonnemann (talk)) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| | ||

'''Original Editors '''- Bruce Tan [[Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems|from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.]] | |||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} </div> | |||

== Definition/Description == | == Definition/Description == | ||

Revision as of 03:18, 22 February 2017

Original Editors - Bruce Tan from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Bruce Tan, Morgan Yoder, Hannah McCabe, Naomi O'Reilly, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Elaine Lonnemann, 127.0.0.1, Wendy Walker, WikiSysop and Kim Jackson </div>

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Heterotopic Ossification (HO) refers to the formation of lamellar bone inside soft tissue structures where bone does not normally exist. This process can occur in structures such as the skin, subcutaneous tissue, skeletal muscle, and fibrous tissue adjacent to bone. In more rare forms, HO has also been described in the walls of blood vessels and intra-abdominal sites such as the mesentery.[1]

Research suggests four factors which contribute to formation of heterotopic bone: 1) inciting event (usually trauma), 2) a signal from the site of injury, 3) a supply of mesenchymal cells whose genetic machinery is not fully committed, 4) an environment which is conducive to the continued formation of new bone.[1] These factors are discussed more indepth in the Etiology/Causes section.

HO was fisrt described by by Patin in 1692 while working with children diagnosed with myositis ossificans progressiva.[2] In 1918, Dejerine & Ceillier detailed the anatomical, clinical, and histological features of ectopic bone formation in soldiers who sustained spinal injuries during World War I.[3]

Following the work of Dejerine & Ceillier, Marshall Urist described the osteoinducive properties of bone morphogenic protein in ectopic areas such as muscle. This was and still is considered a "landmark discovery" in orthopedic research.[4] Two of the original reasearch articles by Urist can be found below:

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

The reported prevelance of heterotrophic ossification is extremely variable. One of the main reasons for this is the fact that not all forms of HO are clinically significant and some patients live with the condition without ever knowing. Recent evidence reports the prevalence of HO as:

- Following lower extremity amputee→ about 7%[4]

- Following traumatic brain injuries→ 11% (ranges reported from 10-20%)[4]

- Following spinal cord injuries→ 20% (ranges reported from 20-40%)[4]

- Following THA→ 53% (ranges reported from 0.6-90%)[5]

- Following TKA→ 15% (ranges reported from 1-42%)[6]

- As of 2005, there were 400 patients known in the U.S. with genetic forms of heterotopic ossification.[1]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Clinical signs and symptoms of HO may appear as soon as 3 weeks or up to 12 weeks after initial musculoskeletal trauma, spinal cord injury, or other precipitating event.[5]

Findings which may suggest the presence of HO are as follows:[3]

- joint swelling and warmth (initial phase)

- joint pain

- palpable mass, firm (late stage)

- decreased ROM of effected joint

Clinical note: the initial inflammatory phase of HO may mimic other pathologies such as cellulitis, thrombophlebitis, osteomyelitis, or a tumorous process.[2]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

The most common conditions found in conjuction with heterotopic ossification include:[2][1]

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Rhuematoid arthritis[7]

- Hypertrophic osteoarthitis

- Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

- Paget's disease

- Quadraplegia and paraplegia

Medications[2][edit | edit source]

Medications are prescribed to patients who are at risk for developing heterotopic ossification for preventative measures and also to aid in the treatment after formation of heterotopic lesions. The two types of medications shown to have both prophylactic and treatment benefits are as follows:

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: NSAIDS

Indomethacin more specifically-two fold action

- inhibition of the differentiation of mesenchymal cells into osteogenic cells (direct)

- inhibition of post-traumatic bone remodelling by supression of prostoglandin-mediated response (indirect)

Anti-inflammatory properties

- Biphosphonates:

Three-fold action

- inhibition of calcium phosphate precipitation

- slowing of hydroxyapatite crystal aggregation

- inhibition of the transformation of calcium phosphate to hydroxyapatite

Clinical Note: clinicians must be aware of potential complications (mainly GI related) with patients taking NSAIDS on a routine basis.

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[2][edit | edit source]

Three-phase bone scinitigraphy:

- both diagnostic and therapeutic follow-up purposes

- most sensitive imaging modality for early detection

- Phases 1 and 2 are indicative of hyperaemia and blood pooling (precursors to process of HO)

- Usually positive after 2-4 weeks

- Serial bone scans used to monitor metabolic activity of HO to determine optimal timing for surgical resection and to predict postoperative occurrence.

Radiography, MRI, CT Scan:

- all have low specificity in early stage of disease process

- better for detection in later stages when ossification is more pronounced

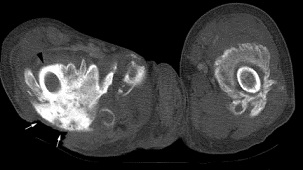

- MRI and CT are valuable pre-operative tools to determine relationship to blood vessels and peripheral nerve structures File:HO MRI.jpgMRI showing heterotopic ossification (arrows)

- HO demonstrable on radiographs 4-6 weeks post-injury

- MRI better than radiograph at detecting HO in early phases

- Plain film radiographs are most commonly used due to their simplicity and low cost.

- Typical radiologic presentation of HO is circumfrential ossification with a lucent center[5]

Prostoglandin E2: (PGE2)

- monitior PGE2 excretion in 24-hour urinalysis

- PGE2 felt to be reliable bone marker for early detection and determining treatment efficacy

- A sudden increase is an indication for bone scintigraphy

Alkaline Phosphatase: (ALP)[4]

- frequently used in early detection of HO

- High sensitivity, low specificity

- Serum ALP levels can be dependent on renal and hepatic function, so they are not always useful.

Ultrasonography:

- earlier detection than conventional ragiograph

- local signs of inflammation in SCI patients are suggestive of HO

- high sensitivity and specificity for early detection of HO 1-week post-THR.

Clinical Note: the lack of simple objective measures in detecting heterotopic bone formation causes HO to be misdiagnosed in the early stages, leading to delayed treatment.[4]

Etiology/Causes[edit | edit source]

There is no uniform agreement concerning the etiology and pathogenesis of heterotopic ossification. The transformation of primitive mesenchymal cells in connective tissue into osteoblastic tissue and osteoid involve diverse and poorly understood triggers. These triggers range from bone morphogenic protein and human skeletal growth factors to genetic, neurologic, and traumatic factors.[8]

HO has been described to occur in five clinical settings:[1]

- Genetic

- Post-traumatic

- Neurogenic

- Post-surgical

- Reactive lesions of hands and feet

Genetic forms include two types:Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressive (FOP) and Progressive Osseous Heteroplasia (POH). These two types are decribed as massive deposits of heterotopic bone around multiple joints in the absence of an inciting event (i.e. trauma).[1]

Post-traumatic HO is generally classified as Myositis Ossificans Circumscripta. It is described as localized self-limited proliferation of fibroblasts and heterotopic bone formation in skeletal muscle following trauma.[1]

Neurogenic HO occurs in patients who have sustained head trauma and spinal cord injuries. Muscles and periarticular fibrous tissues at multiple sites develop heterotopic bone formation.[1]

Post-surgical HO most commonly develops after procedures which require open reducion, internal fixation and joint relacement surgeries, with THA being the most common.[1]

Reactive lesions of the hands and feet are usually associated with the periosteum or periarticular fibrous tissue, which differentiates the category from myositis ossificans. These lesions occur in three clinico-radiologic settings: 1) bizzare parosteal osteochondromatous, 2) florid reactive periositis, and 3) subungual exostoses.[1]

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

Evidence shows that there are no systemic effects secondary to the formation of heterotopic ossification. The most common sites where this condition presents are the hips, knees, spine, elbow, wrists, hands, and any site which is involved in a traumatic event.

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

The treatment of heterotopic ossification is largely dependent on the amount of ectopic bone formation, the location and the associated functional limitations of the patient.

The first goal of medical management is to identify those patients at risk for developing HO and treating them prophylactically (see medications section). Research supports two other approaches for the medical management of HO: 1)surgical excision and 2) radiation therapy.

Sugical intervention:

The two main goals of sugical intervention are to alter the position of the affected joint or improve its range of motion (ROM).[3]. Through his work, Garland has created a recommended timetable for surgical intervention:[9]

- 6 months following traumatic development of HO

- 1-year following development of HO secondary to a spinal cord injury

- 18 months following development of HO secondary to head injury

The above timetables were established to determine the most optimal timing of surgical intervention. Clinicians must determine if the lesion has reached maturation before surgical excision to decrease the risk of intraoperative complcations such as hemorrhage, and the reoccurance of the ectopic lesion.[5] The use of bone scans to determine metabolic activity of the lesion and serum ALP levels are common aids in this decision making process.

Shehab et al. also describe a criteria for recommending surgical removal of heterotopic ossification. The criteria are as follows:[5]

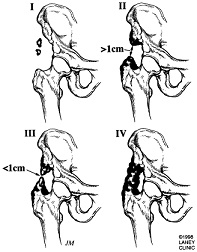

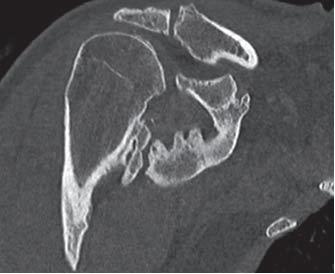

- significantly limited ROM of involved joint (e.g., hip should have < 50o ROM); for most patients, progression to joint ankylosis is the most serious complication of heterotopic ossification.File:Shoulder HO CT3D 2.JPG3D CT reconstruction of same shoulder (Chao et al.)

- Absence of local fever, swelling, erythema, or other clinical findings of actue heterotopic ossification.

- Normal serum alkaline phosphate levels.

- Return of bone scan findings to normal or near normal; if serial quantitative bone scans are obtained, there should be a sharply decreasing trend followed by a steady state for 2-3 months.

Radiotherapy:

- The use of radiotherapy as a prophylactic treatment comes mainly from the literature concerning total hip arthroplasty.[4]

- Radiating pluripotential mesenchymal cells may effectively prevent the development of HO.[7]

- A dose of 700-800 cGy of local radiation in the first four post-operative days has shown to prevent HO formation in patients who are at high risk.[4]

<span id="fck_dom_range_temp_1301766677195_863" /><span id="fck_dom_range_temp_1301766677195_498" />

<span id="fck_dom_range_temp_1301766773393_61" /><span id="fck_dom_range_temp_1301766773393_201" />

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy has been shown to benefit patients suffering from heterotopic ossification. Pre-operative PT can be used to help preseve the structures around the lesion. ROM exercises (PROM, AAROM, AROM) and strengthening will help prevent muscle atrophy and preserve joint motion.

Clinical note: caution must be taken when working with patients with known heterotopic lesions. Therapy which is too aggressive can aggrevate the condition and lead to inflammation, erythema, hemorrhage, and increased pain.

Post-operative rehabilitation has also shown benefit patients with recent surgical resection of heterotopic ossification. The post-op management of HO is similar to pre-op treatment but much more emphasis is placed on edema control, scar management, and infection prevention. Calandruccio et al. outlined a rehabilitation protocol for patients who underwent surgical excision of heterotopic ossification of the elbow. The phases of rehab and goals for each phase are as follows:[10]

Phase I (Week 1)

- Goals

- Prevent infection

- Protect and decrease stress on surgical site

- Decrease pain

- Control and decrease edema

- ROM to 80% of affected joint

- Maintain ROM of joint proximal and distal to surgical site

Phase II (2-8 weeks)

- Goals

- Reduce pain

- Manage edema

- Encourage limited ADL performances

- Promote scar mobility and proper remodeling

- Promote full ROM of affected joint

- Encourage quality muscle contractions

Phase III (9-24 weeks)

- Goals

- Self-manage pain

- Prevent flare-up with functional activities

- Improve strength

- Improve ROM (if still limited)

- Return to previous levels of activity

Casavant and Hastings also provide great insight into the evaluation and management of heterotopic ossification in their article titled Heterotopic Ossification about the Elbow: A Therapist’s Guide to Evaluation and Management.[11]

Clinical Note: The two studies used above were primarily focused on rehabiliatation of the elbow secondary to heterotopic ossification. However, the goals and stages of the rehabilitation process can be used as a guide when treating at other sites.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Since radiography is the most common form of imaging used to diganose heterotopic ossification, the presence of an opaque lesion can mislead the clinician initially. Important categories to consider when contemplating a differential diagnosis for HO include the following:[2],[5]

- Tumors→ osteosarcoma, osteochondroma

K. Liu et al. discuss a variety of tumorous processes which have been assosiated with sites developing HO.[12]

- Infection→osteomyelitis

- Inflammation→ cellulitis

- Circulatory complications→ deep vein thrombosis, thrombophlebitis

Case Reports/ Case Studies[edit | edit source]

Tibiofibular Syndesmosis and Ossification. Case Report: Sequelae of Ankle Sprains in an Adolescent Football Player.

Heterotopic Mesenteric Ossification ("intraabdominal myositis ossificans): A Case Report.

A Case of Psoas Ossification from the use of BMP-2 for Posterolateral Fusion at L4-L5.

- Brower RS, Vickroy NM. A case of psoas ossification from the use of BMP-2

for posterolateral fusion at L4–L5.Spine 2008; 18: 653-655.<span id="fck_dom_range_temp_1299789628126_629" />

Infrapatellar Heterotopic Ossification after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction.

- Valencia H, Gavín C. Infrapatellar heterotopic ossification after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy: Official Journal Of The ESSKA [serial on the Internet. (2007, Jan), [cited March 31, 2011]; 15(1): 39-42. Available from: MEDLINE.]

Heterotopic Ossification of the Ulnar Collateral Ligament: A Description of a Case in a Top Level Weightlifting Athlete.

- A Giombini, L Innocenzi, G Massazza, F Fagnani, et al. Heterotopic ossification of the ulnar collateral ligament: a description of a case in a top level weightlifting athlete. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 2005 Sep 1;45(3): 370-80. In: ProQuest Medical Library [database on the Internet [cited 2011 Mar 31]. Available from: ProQuest; Document ID: 942792311]

Resources

[edit | edit source]

The Mystery of Heterotopic Ossification and How it Affected My Life

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1NOY_AEF8gNY3HRCwoXdtFZj9G-OSG0TNDAFjiqNOh_xvySEXY|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 McCarthy EF, Sundaram M. Heterotopic ossification: a review. Skeletal Radiol 2005; 34: 609-619.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Bossche LV, Vanderstraeten G. Heterotopic ossification: a review. J Rehabil Med 2005; 37: 129-136.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Pape HC et al. Current concepts in the development of hetetrotopic ossification. Journ Bone and Joint Surg 2004; 86: 783-787.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Hsu JE, Keenan MA. Current review of heterotopic ossification. UPOJ 2010; 20: 126-130.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Shehab D, Elgazzar AH, Collier BD. Heterotopic ossification. Jour of Nuclear Medicine 2002; 43: 346-353.

- ↑ Dalury DF, Jiranek WA. The incidence of heterotopic ossification after total knee arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty 2004; 19: 447-457.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Chao ST, Joyce, MJ, Suh JH. Treatment of heterotopic ossification. Ortho 2007; 30: 457-464.

- ↑ Chua K, Kong K. Acquired heterotopic ossification in the settings of cerebral anoxia and alternative therapy: two cases. Brain Injury: [BI] [serial on the Internet]. (2003, June), [cited March 31, 2011]; 17(6): 535-544. Available from: MEDLINE.

- ↑ Garland DE. A clinical perspective on common forms of acquired heterotopic ossification. Clin Orthop 1991; 263: 13-29.

- ↑ Pho C, Godges J. Heterotopic ossification about the elbow: repair and rehabilitation. KPSoCal Ortho PT Residency.

- ↑ Casavant AM and Hasting H. Heterotopic ossification about the elbow: a therapist’s guide to evaluation and management. Journal of Hand Therapy 2006; 19: 255-267.

- ↑ Liu K, Tripp S, Layfield LJ. Heterotopic ossification: review of histological findings and tissue distribution in a 10-year experience. Research and Practice 2007; 203: 633-640.