Differentiating Buttock Pain and Sacroiliac Joint Disorders: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

Buttock pain can be caused by a referred pain from the lumbar spine in the respective dermatome<ref name=":2" />, A study <ref>Eubanks JD, Lee MJ, Cassinelli E, Ahn NU. Prevalence of lumbar facet arthrosis and its relationship to age, sex, and race: an anatomic study of cadaveric specimens. Spine. 2007 Sep 1;32(19):2058-62.</ref> by Eubanks reported significant improvement in buttock pain following facet joint block. | Buttock pain can be caused by a referred pain from the lumbar spine in the respective dermatome<ref name=":2" />, A study <ref>Eubanks JD, Lee MJ, Cassinelli E, Ahn NU. Prevalence of lumbar facet arthrosis and its relationship to age, sex, and race: an anatomic study of cadaveric specimens. Spine. 2007 Sep 1;32(19):2058-62.</ref> by Eubanks reported significant improvement in buttock pain following facet joint block. | ||

{| width="800" border="1" cellpadding="1" cellspacing="1" | |||

|- | |||

! scope="col" | History | |||

! scope="col" | Physical Examination | |||

! scope="col" | Range of Sensitivity/Specificity | |||

|- | |||

| Low back pain | |||

Pain may radiate down to the leg | |||

Electric character of pain | |||

Sitting, standing, changing posture, coughing or sneezing may exacerbate pain | |||

| Lasegue sign (or Straight Leg Raise test) | |||

Inverted lasegue sign (or Cross Straight Leg Raise test) | |||

Femoral nerve stretch test | |||

Slump test | |||

Bowstring sign | |||

Trendelenburg test (L5 radiculopathy) | |||

Sensory deficits | |||

Motor deficits | |||

Altered reflexes | |||

|- | |||

|} | |||

=== Ruling Out the Sacroiliac Joint === | === Ruling Out the Sacroiliac Joint === | ||

Revision as of 22:19, 21 September 2020

Original Editors - Jessie Tourwe

Top Contributors - Mariam Hashem, Kim Jackson, Tarina van der Stockt, Lucinda hampton, Ewa Jaraczewska and Jess Bell

What Is Causing the Pain?[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis of Gluteal or buttock pain is complicated due to the overlapping symptoms of many conditions such as [1]:

- Radicular pain from Lumbar spine origin

- Sciatic nerve entrapment

- Obturator internus/gemellus syndrome

- Piriformis Syndrome

- Quadratus femoris/ischiofemoral pathology

- Problems at the hamstrings

- Gluteal muscles disorders

There are no fixed guidelines for the diagnosis of buttock pain[2].

The complicated anatomy of the Sacroiliac joint, the Lumbar spine and the buttock area makes the differential diagnosis of pain and dysfunction a challenging task.

It is also difficult to use objective assessment measures to differentiate the source of the problem. Imaging such as MRI scans provides valuable information but can often mislead the management since the findings are not always consistent with LBP history and symptoms[3].

Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The Sacroiliac joint is the joint connection between the spine and the pelvis formed by the fusion of the three bones of the pelvis: the ilium, ischium, and pubic bone[4]. The sacroiliac joint has different functions:

- Load transfer between the spine and the lower extremities

- Shock absorption

- Converts torque from the lower extremities into the rest of the body[5].

This region is surrounded by and covered with the dorsal sacral nerve, the iliolumbar ligament, the dorsal sacral ligaments, the erector spinae fascia, which is part of the thoracolumbar fascia and makes palpating specific structures difficult[6].

The subgluteal space is located between the middle and deep gluteal aponeurosis layers. It contains Superior/Inferior gluteal nerves, blood vessels, Ischium, Sacrotuberous/sacrospinous ligaments, Sciatic nerve and Piriformis.

The piriformis muscle is innervated by the branches of the L5, S1, and S2 spinal nerves.

The sciatic nerve has a complicated relationship with the piriformis muscle, passing above, below and through the muscle before and after dividing[1].

Considerations[edit | edit source]

When a patient presents with persisting chronic pain that is not responding to treatment, biopsychosocial factors are often thought to be the reason for chronicity. The development of chronic pain might have been the result of catastrophisation and fear avoidance as a result of a missed primary structural pain.

Impingement of the sciatic nerve occurs mostly in the deep gluteal space and around the piriformis muscle than in the lumbar spine level.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Ruling Out the Lumbar Spine[edit | edit source]

Red Flags are serious pathologies and should be spotted on the first contact.

Spondyloarthropathies and other inflammatory conditions at the lumbar spine level could possibly refer pain to the buttock area. Patients with Ankylosing spondylitis or Reiter's syndrome may present with inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Diverticulitis or Chrohn's disease, prolonged severe morning stiffness, bilateral enthesopathies such as Achilles tendinopathy or Plantar fasciitis.

Gynaecological problems, potential infectious diseases, possible malignancies and patients not responding to physiotherapy management can possibly reflect the presence of serious pathologies[6].

Buttock pain can be caused by a referred pain from the lumbar spine in the respective dermatome[2], A study [7] by Eubanks reported significant improvement in buttock pain following facet joint block.

| History | Physical Examination | Range of Sensitivity/Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Low back pain

Pain may radiate down to the leg Electric character of pain Sitting, standing, changing posture, coughing or sneezing may exacerbate pain |

Lasegue sign (or Straight Leg Raise test)

Inverted lasegue sign (or Cross Straight Leg Raise test) Femoral nerve stretch test Slump test Bowstring sign Trendelenburg test (L5 radiculopathy) Sensory deficits Motor deficits Altered reflexes |

Ruling Out the Sacroiliac Joint[edit | edit source]

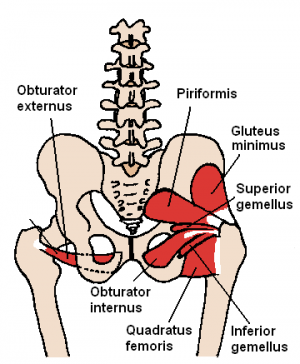

The thoracolumbar fascia, sacroiliac joint, Gluteus max, Gluteus minimus, Piriformis, Obturator Externus and Internus, Gemelli's Superior and Inferior, ischio-gluteal bursa, the long dorsal ligament, sacrotuberous ligament, sacrospinous ligament and the posterior capsule of the hip are all nociceptive structures that can trigger posterior hip pain[6].

Numerous neural structures can also be involved such as the dorsal sacral nerve, the lumbosacral plexus, including the sciatic nerve and the pudendal nerve which can be highly implicated in sexual dysfunction and pelvic floor dysfunction.

Any pain from the sacroiliac joints or the surrounding myofascial, nerve or neural structures, connective tissues and ligament structures is considered Sacroiliac dysfunction.

This pain could be gradual, due to maladaptive postures, seronegative spondyloarthropathies, osteoarthritis, pregnancy-related pain, or sudden often due to sudden movement, strain or trauma, for example, missing a step or unilateral loading with a twist which can be accompanied by a click. Pain can refer to the pubic symphysis, the groin, the coccyx , and the posterior thigh.

Symptoms vary from difficulties with standing, walking, walking up the stairs, squatting getting out of the car, turning in bed which causes sleep disturbance.

Psychosocial factors can influence the presentation and the symptoms.

Other associated symptoms: pelvic organ dysfunction, such as urinary incontinence, prolapse, or constipation and sexual dysfunction, It can also be associated with respiratory distress such as aberrant breathing patterns. There is some suggestion of links of the lateral erector spinae, such as iliocostalis linking T12 to L1 down onto the sacrum.

Special Tests

March test was validated by Hungerford in 2004. The validation study was published before much was known about other nociceptive structures or pathological structures in the lumbar spine or in the buttock. The March test is a load transfer test of the ability of the pelvic girdle to transfer a load when lifting the opposite leg, A positive test however doesn't show where the failure of load transfer happened (on which level).

Active straight leg raise test. Is used clinically to isolate the sacroiliac joint however, it's not specific and cannot be relied on in determinning the cause of the pain. The active straight leg raise test is a validated test but doesn't rule out other pelvic girdle dysfunctions

Same applies to Laslett's composite tests and tests that are based on palpation or positional faults

The one-legged squat test, femoral glide test. passive accessory tests: AP glide and the longitudinal glide to assess stability at the joint. However, these tests are unvalidated but you can compare glide within the same patient between the right and left sides.

The Pelvic joint compression with the use of a sacroiliac belt can be very helpful to help control and increase force closure across that lumbar-pelvic area.

Imaging

X-rays don't rule out which tissue is involved.

Sacroiliac Joint Infiltration can ease the symptoms when injecting an anesthetic, it doesn't differentiate what the pathological structure is.

Management

The language we use is important. Diagnosing the joint as locked, out of alignment, or positional fault which is not supported by evidence. Patients often develop fears and anxieties in response to the beliefs explained by the physiotherapists and consequently catastrophise their symptoms. of the patient.

A suggested alternative is explaining the symptoms to the patient using motor control examples, for example, here is a little bit of less control around this region and we need to restore it.

Ruling Out Deep Gluteal pathology[edit | edit source]

Gluteal Tendinopathy is characterized by chronic, intermittent pain over the buttock and lateral aspect of the thigh.

Symptoms are mainly located in the inferior gluteal aspect '' retro-trochanteric'' between the ischial tuberosity and the surrounding structures radiating onto the back of the greater trochanter.

The pain might also be originating at the lesser trochanter which could possibly reflect ischio-femoral impingement,

The definition of greater trochanteric pain syndrome has now been expanded upon to include the insertional region of the Gemelli's and the Obturators.

Patients with Gluteal tendinopathy present with sleep disturbance and difficulties with physical activity and quality of life affected similarly to those awaiting a hip replacement for severe osteoarthritis (Angie Fearon). Up to 70% of people suffering from gluteal tendinopathy are menopausal or peri-menopausal females so it's important to rule out gynaecological pathologies.

Pain can refer to the groin, the coccyx, the anterior thigh, the lateral thigh around the sacroiliac joint, the buttock and down to the insertion of the iliotibial tract on the proximal tibia[8] which makes it more difficult to differentiate it from SIJ.

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Carro LP, Hernando MF, Cerezal L, Navarro IS, Fernandez AA, Castillo AO. Deep gluteal space problems: piriformis syndrome, ischiofemoral impingement and sciatic nerve release. Muscles, ligaments and tendons journal. 2016 Jul;6(3):384.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Shim DM, Kim TG, Koo JS, Kwon YH, Kim CS. Is it radiculopathy or referred pain? Buttock pain in spinal stenosis patients. Clinics in orthopedic surgery. 2019 Mar 1;11(1):89-94.

- ↑ Tonosu J, Oka H, Higashikawa A, Okazaki H, Tanaka S, Matsudaira K. The associations between magnetic resonance imaging findings and low back pain: A 10-year longitudinal analysis. PLoS One. 2017 Nov 15;12(11):e0188057.

- ↑ Dutton M. Orthopaedic Examination, Evaluation, and Intervention. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 2008.

- ↑ Sacroiliac Joint. Physiopedia Page (last accessed 20/09/2020) Available from: https://physio-pedia.com/Sacroiliac_Joint#cite_note-Dutton-2

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Bell-Jenje T. Differentiating Buttock Pain and Sacroiliac Joint Disorders. Physioplus Course 2020

- ↑ Eubanks JD, Lee MJ, Cassinelli E, Ahn NU. Prevalence of lumbar facet arthrosis and its relationship to age, sex, and race: an anatomic study of cadaveric specimens. Spine. 2007 Sep 1;32(19):2058-62.

- ↑ Zibis AH, Mitrousias VD, Klontzas ME, Karachalios T, Varitimidis SE, Karantanas AH, Arvanitis DL. Great trochanter bursitis vs sciatica, a diagnostic–anatomic trap: differential diagnosis and brief review of the literature. European Spine Journal. 2018 Jul 1;27(7):1509-16.