Congenital Spine Deformities

Top Contributors - Ine Van de Weghe, Gertjan Peeters, Lucinda hampton, Scott Cornish, Kim Jackson, Admin, WikiSysop, Mande Jooste, Chelsea Mclene, De Maeght Kim and Mila Andreew

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Congenital spine deformities are disorders of the spine that develop in an individual prior to birth. The vertebrae do not form correctly in early fetal development and in turn cause structural problems within the spine and spinal cord. These deformities can range from mild to severe and may cause other problems if left untreated, such as developmental problems with the heart, kidneys and urinary tract, problems with breathing or walking, and paraplegia (paralysis of the lower body and legs).

Medical researchers are still unsure of what actually causes the defects responsible for congenital spine deformities. In these disorders, the vertebrae are often missing, fused together and/or misshapen or partially formed.[1]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The causes of congenital vertebral anomalies are likely to be genetic factors, including defects in the Notch signalling pathways. The Notch 1 gene has been shown to coordinate the process of somitogenesis by regulating the development of vertebral precursors in mice. Chromosome 13 and 17 translocations have been associated with the development of hemivertebrae. Genetic theories are supported by molecular, animal, and twin population studies, including several demonstrations of abnormal HOX gene expression. Environmental factors have also been suggested, and these include exposure to toxins including carbon monoxide, the use of antiepileptic medication, and maternal diabetes.[2]

Types[edit | edit source]

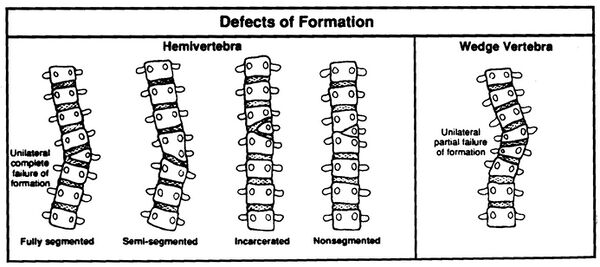

The spectrum of congenital deformities of the spine includes a range of conditions that blend gradually from scoliosis through kyphoscoliosis to pure kyphosis. These deformities occur when an asymmetric failure of development of one or more vertebrae results in a localized imbalance in the longitudinal growth of the spine and an increasing curvature affecting the coronal and/or sagittal plane, with a risk for progression during skeletal growth.

- The consequence of unbalanced growth of the spine can be the development of a benign curve with slow or no progression, in which case observation may be the only treatment required.

- There are types of vertebral abnormalities that can produce considerable asymmetry in spinal growth and the development of very aggressive deformities with consequent functional, cosmetic, respiratory, and neurologic complications. Understanding the anatomical features of the individual vertebral anomalies and their relation to the remainder of the spine makes it possible to predict those abnormalities that are likely to produce a severe curve. Recognizing the natural history of the deformity at an early stage can in turn allow appropriate surgical treatment, with the aim of preventing the development of severe spinal curvature and trunk decompensation that would require much more complex and dangerous treatment with a suboptimal clinical outcome.[2]

Examples of a failure of segmentation are:

- Congenital Thoracic Hyperkyphosis

- Congenital Scoliosis

Examples of a failure of formation are:

- Klippel-Feil syndrome [3]

- Congenital kyphosis

- Congenital Scoliosis

The anomaly is present at birth, so a curvature is noted much earlier than patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Large deformities can result due to the number of years of growth remaining. [4]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Congenital abnormalities of the spine have a range of clinical presentations. Some congenital abnormalities may be benign, causing no spinal deformity and may remain undetected throughout a lifetime.

Some deformities will result in sagittal plane abnormalities, for eg kyphosis or lordosis, whereas others will primarily affect the coronal plane eg scoliosis. The resultant spinal deformity is often a complex, three-dimensional structure with differences in both the coronal and sagittal plane, along with a rotational component along the axis of the spine.[5]

Symptoms of Congenital Spine Deformities:

Doctors often detect any spine deformity at birth if there is any abnormal curvature in the back. However, some spine deformities until later in childhood and/or adolescence when symptoms worsen. Physical signs of congenital spine deformities typically include:

- Tilted pelvis

- Difficulty walking

- Difficulty breathing

- Abnormal curvature or twisting in the back, left or right, forward or backward

- Uneven shoulders, hips, waist or legs

Treatment[edit | edit source]

In most cases, nonoperative treatment options are recommended before surgery is considered. Nonoperative treatment options typically include pain medication, certain braces and physical therapy (that includes gait and posture training).

Surgery Is Considered If:

- The spinal deformity is progressing

- The condition has caused unbearable physical deformity

- The patient experiences chronic pain that cannot be relieved by nonoperative treatment options

- The condition has caused compression of the nerve roots or spinal cord

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Most congenital spine deformities are diagnosed in the uterus, and if not, at birth. as they are clearly present e.g. Spina Bifida, scoliosis. Some disorders, however, might not become symptomatic until childhood or even adulthood [6] In these cases, MRI scans or ultrasound can be used to diagnose the specific disorder, [7] therefore, for many conditions there is not a differential diagnosis as the deformity/anomaly will be clear on an MRI

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

There are several different procedures that can be used to carry out the imaging of the spine. The choice of imaging depends on what is required to be analysed, such as bone vs spinal canal. In children, it is important to start with less invasive procedures such as the United States, due to their cartilage and non-ossified bones. [7]

X-Rays are useful for showing structural deformities such as hemivertebrae, butterfly vertebra, or incomplete fusion of posterior elements. X-ray is used if no imaging of the spinal cord is required. For scoliosis, erect posterior-anterior frontal and/or lateral views (with breast shielding) are usually obtained. [8]

MRI is most frequently used for imaging of the spine in adults as the spinal canal and its content can be analysed.

Basu et al. suggest that MRI and echocardiography should be an essential part of any evaluation of patients with congenital spinal deformity, [9] with numerous other studies demonstrating the high degree of confidence with MRI use. [10] [11] [7] [12] [13]

CT Scans continue to be the preferred method for the assessment of localised bony abnormalities, or a calcified component, of the spinal canal, foramina, neural arches, and articular structures. [8]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

These are the most commonly used questionnaires with patients who have undergone spinal surgery, the most common treatment for congenital spine deformities.

- The Balanced Inventory for Spinal Disorders [14]

- Owestry Disability Index [15] [16] [17]

- The physical component summary [15]

- The Short Form of the Medical Outcomes Study [15] [17]

- Brief Pain Inventory [16]

- Roland–Morris disability questionnaire [16] [17]

- SRS-22 Questionnaire [18]

Examination[edit | edit source]

The physical examination of a patient with kyphosis has various components: [19]

- Postural analysis, which may reveal a gibbus deformity or a round back.

- Palpation to assess for spinal abnormalities and may identify tenderness of the paraspinal musculature, which is often present.

- Range of motion during flexion, extension, side bending and spinal rotation of the back. Asymmetry is be noted. Adam’s forward bend test may reveal a thoracolumbar kyphosis, although Karachalios et al suggested that this test is not a sure diagnostic criterion for the early detection of scoliosis due to the unacceptable number of false-negative findings. [20] Rather, the combined back-shape analysis methods is recommended.

Côté Pierre et al. however, suggested that the Adam’s forward band test is more sensitive compared to the scoliometer and consider it to be the best non-invasive clinical test to evaluate scoleosis. [21]

A complete neurologic evaluation should also be carried out to rule out in the presence of intraspinal anomalies [19]. Patients with congenital spondylolisthesis show deficits in their neurological examinations. [22] A neurological evaluation includes an evaluation of pain, numbness, paresthesia, tingling, extremity sensation and motor function, muscle spasm, weakness and bowel/bladder changes. [17]

For the examination of spina bifida oculta, X-ray examination is the only valid test to confirm this type of neural tube defect. [23]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

The natural history, the character and location of the deformity ultimately influence the choice of treatment.[24] Spinal instrumentation for congenital spine deformity cases is safe and effective, [25] [26] as is growing rod surgery for selected patients with congenital spinal deformities. [27] [28] The size and weight of the patient determines the size of the spinal implants, whereas the surgical fixation anchors are determined by the anatomy of the patient and the anomalies present. [26] The complications associated with the use of this spinal instrumentation are infrequent and the curve correction, length of immobilisation and fusion rate is improved.[26]

Growing Rod Surgery[edit | edit source]

Growing rod surgery is one of the options for the correction of scoliosis, a modern alternative treatment for young children with early onset scoliosis. Elsebai HB et al. focused on its use in progressive congenital spinal deformities. The incidence of complication remained relatively low [27] [28] and is also recommended for patients where the primary problem is at the vertebral column.

Expansion Thoracostomy and VEPT[edit | edit source]

For severe congenital spine deformations, when a large amount of growth remains, expansion thoracostomy and VEPTR (a curved metal rod designed for many uses), are the most appropriate choice. These methods are used when the primary problems involve the thoracic cage, for example when there are rib fusions and/or with developing Thoracic Insufficient Syndrome, [28] but the incidence of complications using VEPTR is, however, relatively high.[29]

Resection and Fusion[edit | edit source]

For treating congenital scoliosis caused by hemivertebra posterior hemivertebra, resection and monosegmental fusion appears to be effective. This treatment results in an excellent correction in both the frontal and sagittal planes. [30] Early surgery is typically prescribed as a treatment for children with congenital scoliosis, even though there is little evidence for its long term results. Evidence base is also lacking to confirm the hypothesis that spinal fusion surgery for children with congenital scoliosis is effective Additionally, there are conflicting data about the safety of hemivertebra resection and segmental fusion which uses pedicle screw fixation. [29]

Physical Therapy Management [edit | edit source]

Physical therapy helps patients to continue with daily activities. There are various interventions for congenital spine deformities, such as bracing and postural training and surgical, as described under medical management.

Scoliosis[edit | edit source]

Various approaches for conservative management of scoliosis can be considered, although opinions are divided for early treatment. Braces cannot correct a spinal curve, but they can be used for preserving the spine's shape and delaying early surgery. [31] [32]. It is important, therefore, that conservative management is considered before surgery. External support with casts or braces is considered to be successful in only a small percentage of cases and that surgery is the definitive treatment [33], although this is refuted by Fender et al. who claim that surgical intervention during infancy is the aim of the treatment before compensatory curves can develop. [34]

Few cases have been reported on the influence of conservative treatment. Kaspiris et al claim that segmentation failure should be treated with early surgery before growth in puberty. For scoliosis due to failure of formation, further investigation is needed to determine whether a conservative approach would be necessary.[35] . More research is needed to prove the effectiveness of conservative treatment in congenital scoliosis.

Numerous brace designs have been developed for the spine. The type of brace chosen depends on different factors such as:

- Location of the curve

- Flexibility of the curve

- Number of curves and position and rotation of some of the vertebrae.

Braces have to be worn until the patient stops growing, then surgery can take place. [36]

Milwaukee brace: used for scoliosis. The brace is initially worn for a limited number of hours until the patient is can comfortably wear it all day and night to eventually lead a normal life. The brace may only be removed once a day.

Creswell suggested 2 exercises that the patient should do while wearing this brace:

- Standing, displace the trunk away from the primary lateral pressure pad.

- Standing, breathe in and expand chest posteriorly on the side opposite to primary pressure pad. [36]

When the brace can be discarded, the patient should gradually reduce its use, so long as their posture remains unchanged. During periods where the brace is not worn, it is recommended that the patient is as active as possible. [36]

Until surgery takes place exercise has to be done twice daily to maintain and improve mobility in multiple directions, especially for spinal extension and strength of the trunk muscles. There are different sorts of exercises for every age.

Creswell suggests the Klapps' protocol: [36]

- Teach correct pelvic tilting in supine lying, prone lying, standing, and kneestanding.

- Teach the patient to correct their posture infront of a mirror, so that the shoulders are directly above the pelvis.

- If the primary curve is deteriorating or measures 25° or more, patients aged 2 1/2 years upwards are fitted with a Milwaukee Brace. Once this is fitted, it is worn day and night and is removed only once daily for bathing and exercises.

- If at any time the curve continues to deteriorate rapidly even with a Milwaukee Brace, the patient may have a corrective localised plaster jacket applied for a period of 3 to 4 months. This is put on with the patient lying on a frame, with traction. Jacket use usually considerably improves the scoliosis. When the jacket is removed, Milwaukee Brace use is resumed immediately and exercises are again done regularly.

- The patient stays in the Milwaukee Brace for a number of years, until surgery is undertaken, or until all the following criteria are satisfied:

- They are no longer growing

- They are able to easily maintain the same posture out of the brace as in it

- X-rays of the pelvis show that the iliac apophyses have closed posteriorly. [36]

Post surgery rehabilitation is essential. Children who undergo anterior and posterior hemivertebral excision have to wear a plaster for 3 months to maintain the spinal correction. After 3 months of immobilisation, retraining of the postural muscles is crucial to maintain the stability of the spine. [37]

Kyphosis[edit | edit source]

If kyphosis isn't treated, the curve will continue to progress at approximately 7 degrees each year. During the adolescent growth spurt, the curve will reach its maximum orientation and brace treatment during this period was seen to be ineffective. [38]

When operative treatment doesn't take place, patients with myelomeningocele and congenital kyphosis can be managed by modified wheelchairs and orthoses. Patients are able to function with reasonable comfort with these wheelchair modifications.

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Congenital spine deformities are identified in the uterus or at birth which are the result of anomalous vertebral development in the embryo. They can classified into three groups:

- Due to neural tube deformities/defects,

- Due to failure of segmentation

- Due to failure of formation.

Numerous factors such as environmental factors, genetic factors, vitamin deficiency, chemicals and drugs, singly or in combination, have been implicated in the development of congenital abnormalities during the embryonic period. Diagnose imaging is used to confirm a deformity, such as ultrasound, X-rays, MRI and CT scans.

With children, it is important to start with a less invasive procedure due to their cartilage and non-ossified bones, such as ultrasound. Diagnose is completed with observation, palpation, assessment of range of motion of the spine and a neurological evaluation. If the patient has an open deformity due to a tube defect, surgery is done directly after birth or surgery can be delayed in the case of a closed deformity due to neural tube defect. There is some debate over the treatment of congenital spine deformities due to a failure of segmentation/formation with some clinicians recommending surgery during infancy, whereas others would initially treat using conservative management techniques, such as braces and exercise, before considering surgery.

Congenital scoliosis presents a major challenge to the clinician due the wide variety of primary and secondary abnormalities. These abnormalities develop during fetal development and treatment often necessitates numerous tests and thorough, repetitive examinations.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Khavkinckinic Congenital spinal deformities Available:https://khavkinclinic.com/congential-spine-deformities/ (accessed 10.10.2021)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Musculoskeletalkey 6 Congenital Deformities of the Spine Available: https://musculoskeletalkey.com/6-congenital-deformities-of-the-spine/ (accessed 10.10.2021)

- ↑ Klemme WR et al. (2001). Hemivertebral excision for congenital scoliosis in very young children. J Pediatr Orthop. 21 (6), pp761-764.

- ↑ Lonstein J.E. (1999). congenital spine deformaties: scoliosis, kyphosis, and lordosis. orthopedic clinics of north america, 30 (3), pp387-405

- ↑ Kawakami N, et al. (2009). Classification of congenital scoliosis and kyphosis: a new approach to the three-dimensional classification for progressive vertebral anomalies requiring operative treatment, Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 34 (17), pp1756-65

- ↑ SCHWARTZ E.S. and ROSSI A., 2015 “Congential spine anomalies: the closed spinal dysraphisms“, Advances in Pediatric Neuroradiology, vol. 45, supp. 3, p. 413-419,

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 SORANTIN E. et al., 2008 “MRI of the Neonatal and Paediatric Spine and Spinal Canal“, European Journal of Radiology, vol. 68, nr. 2, p. 227 – 234

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Patrick D Barnes. (2009). Pediatric radiology : chapter 9, spine imaging. (3). Mosby

- ↑ Basu S.et al., 2002 “Congenital Spinal Deformity: A Comprehensive Assessment at Presentation“, Spine, Vol 27, nr 2, pp 2255-2259

- ↑ Fabry G. (2009). Clinical practice: the spine from birth to adolescence, Eur J Pediatr, 168 (12), pp1415-1420

- ↑ Durand D.J., Huisman T.A., Carrino J.A. (2010). MR imaging features of common variant spinal anatomy, Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am, 18 (4), pp717-726

- ↑ . Grimme J.D. (2007). Castillo M. Congenital anomalies of the spine. Neuroimaging Clin N Am, 17 (1), pp 1-16

- ↑ Brophy JD et al. (1989). Magnetic resonance imaging of lipomyelomeningocele and tethered cord, Neurosurgery, 25 (3), pp336-340

- ↑ SVENSSON E. et al., 2009 “The Balanced Inventory for Spinal Disorders: The validity of a Disease Specific Questionnaire for Evaluation of Outcomes in Patients With Various Spinal Disorders“, Spine, vol. 34, nr. 18, p. 1976 – 1983

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 COPAY A.G. et al.2008 “Minimum Clinically important difference in lumbar spine surgery patients: a choice of methods using the Oswestry Disability Index, Medical Outcomes Study Questionnaire Short Form 36, and Pain Scales“, The Spine Journal, vol. 8, nr. 6, p. 968 – 974, .

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 DEVIN C.J. and McGIRT M.J.2015, “Best evidence in multimodal pain management in spine surgery and means of assessing postoperative pain and functional outcomes“, Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, vol. 22, nr. 6, p. 930 – 938,

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 BOOS N. and AEBI M. (2008) Spinal Disorders, Fundamentals of Diagnosis and Treatment, Springer, p. 311, 434, 695-696

- ↑ FARLEY F.A. M.D. et al .2014, “Congenital Scoliosis SRS-22 Outcomes in Children Treated With Observation, Surgery, and VEPTR“, Spine, vol 39., nr. 22. p. 1868 – 1874,

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Chaén G., Dormans J.P. (2009). Update on congenital spinal deformities: preoperative evaluation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1;34(17), pp1766-1774

- ↑ Karachalios Theofilos et al.,1999 “Ten-Year Follow-Up Evaluation of a School Screening Program for Scoliosis: Is the Forward-Bending Test an Accurate Diagnostic Criterion for the Screening of Scoliosis? “, Spine, Vol 24, nr22, pp 2318

- ↑ . Côté Pierre et al., “A Study of the Diagnostic Accuracy and Reliability of the Scoliometer and Adam's Forward Bend Test“, Spine, Vol. 23, nr. 7, pp 796–802, 1 April 1998

- ↑ Kaplan K.M et al. (2005). Embryology of the spine and associated congenital abnormalities. Spine J, 5 (5), pp 564-576.

- ↑ AKBARNIZ B. A. et al. (2011). The Growing Spine, Management of Spinal Disorders in Young Children. Springer, p. 247, 263, 318.

- ↑ Alexander PG. and Tuan RS. (2010). Role of environmental factors in axial skeletal dysmorphogenesis. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today, 90 (2), pp 118-132

- ↑ Hedequist D.J. (2009). Instrumentation and fusion for congenital spine deformities, Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1;34 (17), pp1783-90

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Hedequist D.J. et al. (2004). The safety and efficacy of spinal instrumentation in children with congenital spine deformities, Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 15;29 (18), pp 2081-2086

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Elsebai HB et al.,2011 “Safety and Effficacy of Growing Rod Technique for Pediatric Congenital Spinal Deformities“, J Pediatr Orthop, vol 31, nr 1, pp 1-5. Jan-Feb,

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Yazici M. and Emans J.2009, “Fusionless Instrumentation Systems for Congenital Scoliosis: Expandable Spinal Rods and Vertical Expandable Prosthetic Titanium Rib in the Management of Congenital Spine Deformities in the Growing Child“, Spine, Vol 34, Nr 17, pp 1800-1807

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Moramarco M and Weiss HR. (2015). Congenital Scoliosis, Curr Pediatr 2015 Nov 17

- ↑ Zhu X. et al. 2014, “Posterior hemivertebra resection and monosegmental fusion in the treatment of congenital scoliosis. “, Article from Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of England, Vol 96, Nr5, pp. 41-44

- ↑ Götze HG. (1978). Prognosis and therapy of the congenital scoliosis, Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb., 116 (2), pp258-266 LoE 5

- ↑ Rolton D. et al. 2014, “Scoliosis: a review Paediatrics and Child Health“, Vol 24, nr 5, pp 197–203, LoE 2a

- ↑ Leatherman K. et al. Two-stage corrective surgery for congenital deformities of the spine. journal of bone and joint surgery, pp 324-328 LoE 2b

- ↑ Fender, D. et al. 2014 “Spinal disorders in childhood II: spinal deformity“, Surgery (Oxford), Vol. 32, Nr1, pp 39–45, LoE 5

- ↑ Kaspiris A., Theodoros B. Grivas, Weiss H-R. and Turnbull D.2011, “Surgical and conservative treatment of patients with congenital scoliosis: a search for long-term results“, Scoliosis, Vol. 6, nr. 12, pp. 1-17, . LoE 2b

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 Creswell E.J.1969, “The conservtaive managment of scoliosis in children and adolescents, and the use of the milwaukee brace “, Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, Vol. 15, Nr.4, pp 149–152, LoE 5

- ↑ Klemme WR et al. (2001). Hemivertebral excision for congenital scoliosis in very young children. J Pediatr Orthop. 21 (6), pp761-764 LoE 2b

- ↑ Winter R.B, Moew J.H, Wang J.F,(1973). Congenital Kyphosis its natural history and treatment as observed in a study of one hunderd and thirthy patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 55 (2), PP 223 -274 LoE 5