Colorectal Cancer

Original Editors - Jacqueline Lopez Abby Schnur from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Jacqueline Lopez, Abigail Schnur, Lucinda hampton, Elaine Lonnemann, Kirenga Bamurange Liliane, Kim Jackson, Vidya Acharya, Admin, Aminat Abolade, Michelle Laine, Evan Thomas and George Prudden

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a rapid abnormal cell growth that affects the large intestines and/or rectum.

- These clusters of cells are called adenomatous polyps and develop from the tissue membrane of glandular tissue.

- Polyps can start as benign and non-cancerous but with time can develop and become cancerous.[1]

Colorectal cancer

- Third most common cancer diagnosed in both men and women in the U.S.

- Death rate from colorectal cancer has been dropping for the past 30 years but still the second leading cause of cancer death in the U.S.

- Overall lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer is: 1 in 21 for men and 1 in 23 for women.

- There are currently more than one million colorectal cancer survivors in the U.S[2].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common cancers

- CRC is one of the leading causes of cancer death worldwide - it is the second most common cause of cancer death in Europe and the United States

- Worldwide in 2008, 1.23 million cases of CRC were reported to be responsible for 9.7% of the total cancer burden, after lung (1.61 million cases) and breast cancer (1.38 million cases)

- It is the first frequently diagnosed cancer in Europe

- It is the 4th most frequently diagnosed cancer in the USA[3]

Approximately 20-25% of patients with CRC present with metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis and 20-25% of patients will develop metastases after treatment, resulting in a relatively high overall mortality rate of 40-45%[3]

- The lifetime risk of developing CRC is 1/20 or 4.96%.[4]

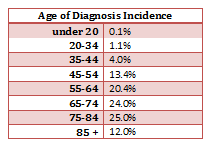

- The mean age of CRC diagnosis is 69 years of age. [5]

- The mean mortality age of CRC is 74 years of age. [5]

- Studies between 1991 and 2005 show that survival rates from CRC have increased by 30%. [6]

- The risk of getting CRC increases with age and is greater in men than women. [7]

- The most common area of diagnosis is the rectum and the rectosigmoid junction, with the sigmoid resulting the most favorable outcome. [8]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Multifactorial etiology including: genetic factors; lifestyle; environmental risk factors (all have substantial effects on CRC development).

- Several risk factors have been identified for CRC (low-fibre and high-fat diet, sedentary lifestyle, diabetes, obesity, smoking, alcohol, advanced age and inflammatory bowel disease).

- In recent years, the increase in CRC incidence is attributed to the increase in the elderly population, changes in dietary habits and increased risk factors such as smoking, low physical activity and obesity[9].

- Lifestyle factors and obesity affect the development of various types of cancer, particularly CRC.

- Colon cancer originates from rapid cell proliferation of the epithelial cells called colonocytes that line the bowel, and somatic mutations in the p53 tumor-suppressor gene. The majority of CRCs are believed to occur sporadically leaving only about 10% to 20% of CRCs to have a known hereditary component

- A synergistic association is observed between physical inactivity and obesity. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has reported that 25% of all the cancer cases worldwide are caused by obesity and sedentary lifestyle[9]

Pathology[edit | edit source]

Colorectal cancers:

- 98% are adenocarcinomas, arising in the vast majority of cases from pre-existing colonic adenomas (neoplastic polyps), which progressively undergo a malignant transformation as they accumulate additional mutations ie the multihit hypothesis

- Metastases may be widespread in advanced disease, although the liver is by far the most common site involved.[10].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Clinical presentation is typically insidious:

- altered bowel habit (constipation and/or diarrhoea)

- iron deficiency anaemia (chronic occult blood loss)

However initial manifestation may be acute:

- bowel obstruction

- intussusception (a painful form of bowel blockage in which one part of the intestine slides inside another part. It can cause swelling that can lead to intestinal damage).

- heavy rectal bleeding

Occasionally metastatic disease may be the first sign.

Positive blood cultures or bacterial endocarditis with Streptococcus bovis is strongly suggestive of underlying colorectal cancer.

In general:

- right sided tumours are larger and present with a mass, distant disease or iron deficiency anaemia

- left sided tumours present earlier with altered bowel habit [10]

Common systemic symptoms of CRC include:

- Unexplained weight loss

- Unexplained loss of appetite

- Nausea or vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Anemia

- Jaundice

- Weakness or fatigue[11]

In many cases colorectal cancer is not discovered until it has become metastatic to other locations in the body. CRC most commonly metastasizes to the liver. It will also commonly metastasize to the lung, brain and bone, but it is uncommon to find one of these metastasis without the presence of a metastatic spread to the liver as well. [8]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Approximately 51-59% of individuals with a diagnosis of CRC who are under the age of 70 do not also suffer from co-morbidities; however, in the individuals who are greater than 70 years of age, only 26-24% of them do not suffer from co-morbidities. Of this group greater than 70 years of age, the men have the highest prevalence of complicating co-morbid conditions. These conditions can have a marked impact on the treatment of the individual’s CRC diagnosis. The short-term survival is also worsened in the presence of co-morbid conditions, especially cardiovascular co-morbidities.

- Cardiovascular disease

- Previously diagnosed CA

- Male – Large Bowel, Urinary Tract, Lung, and Prostate

- Female – Large Bowel, Breast, and Female Genital System

- Hypertension (F>M)

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Diabetes[12]

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[4][edit | edit source]

In addition to a physical examination, the following tests may be used to diagnose colorectal cancer.

- Colonoscopy.

- Allows the doctor to look inside the entire rectum and colon while a patient is sedated. If colorectal cancer is found, a complete diagnosis that accurately describes the location and spread of the cancer may not be possible until the tumor is surgically removed.

- Biopsy removal of a small amount of tissue for examination under a microscope).

- Molecular testing of the tumor. Results of these tests can help determine your treatment options.

- All colorectal cancers should be tested for problems in mismatch repair proteins, called a mismatch repair defect (dMMR).

- For metastatic or recurrent colorectal cancer, a sample of tissue from the area where it spread or recurred is preferred for testing, if available.

- Blood tests.

- CRC often bleeds into the large intestine or rectum, people with the disease may become anemic. A test of the number of red cells in the blood, which is part of a complete blood count (CBC), can indicate that bleeding may be occurring.

- Another blood test detects the levels of a protein called carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). High levels of CEA may indicate that a cancer has spread to other parts of the body.

- Computed tomography (CT or CAT) scan.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI is the best imaging test to find where the colorectal cancer has grown.

- Ultrasound.

- Endorectal ultrasound is commonly used to find out how deeply rectal cancer has grown and can be used to help plan treatment. However, this test cannot accurately detect cancer that has spread to nearby lymph nodes or beyond the pelvis. Ultrasound can also be used to view the liver, although CT scans or MRIs (see above) are better for finding tumors in the liver.

- Chest x-ray - An x-ray of the chest can help doctors find out if the cancer has spread to the lungs.

- Positron emission tomography (PET) or PET-CT scan.

- A PET scan is usually combined with a CT scan (see above), called a PET-CT scan. A PET scan is a way to create pictures of organs and tissues inside the body.[13]

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health

Cancer Advances in Focus: Colorectal Cancer

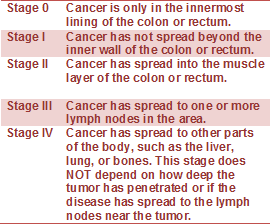

Staging of Colorectal Cancer

If cancer is detected, it will be categorized in a stage to enable the doctor to determine the best type of treatment for the patient. Tumor size does not directly correlate with the stage of cancer.

| Colonoscopy | Scopes the entire colon to look for any polyps or abnormal findings, can also be an opportunity for a biopsy | |

| Proctocolectomy with ileostomy |

(with possible ileum pouch to preserve bowel function) The large intestine and rectum is removed. Lymph nodes may be removed if needed. |

|

| Colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis (IRA) | Part or all of the large intestine is removed and the iluem is joined with the rectum. |

|

|

Proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA)

|

Also called a J-pouch

a pouch is created from the end of a patient’s small intestine and attached to the anus

|

|

| Colostomy |

Permanent. When bowel resection is not possible or colon & rectum are removed. It is a surgical procedure where an opening is made in the abdomen called a stoma or colostomy. A disposable colostomy pouch is attached for disposal of wastes. Hygiene is important to decrease risk of infection. |

|

| Protoscopy | (scope of the rectum): follows post 6 months colectomy to reevaluation and check for polyps. | |

| Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA) |

Intense heat to burn away tumors within the liver. Guided by a CT scan, a doctor inserts a needle-like device that delivers heat directly to a tumor and the surrounding area. This offers an alternative for destroying tumors that cannot be surgically removed. Chemotherapy is sometimes combined with RFA for tumor destruction. |

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy is used after a diagnosis of CRC to help build strength and endurance to continue to perform daily activities. This is used when patients are not receiving treatment, as well as, during chemotherapy and radiation therapy. The main concept that is used is energy conservation to be able to complete tasks without becoming so fatigued that when completed they aren't able to do any more activities. A cross-sectional study in patients recently diagnosed with colorectal cancer comparing their muscle mass, core strength, and physical fragility with those of healthy subjects showed reduced muscle mass and power in the abdominal and lumbar muscles suggesting better outcomes in these patients with an early introduction of strength-enhancing programs[14].

An oncology rehabilitation therapist is usually either an occupational or physical therapist; they have an expertise when treating people with cancer. These therapists create patient-specific exercise programs. The goals of these treatment programs include:

- Minimizing fatigue

- Optimizing physical function

- Boost their immune system

- Improve bowel habits

- Improve flexibility [15]

- Reduce stress and anxiety

- Minimize depression

- Enhance self-image

Research shows better outcomes with preoperative supervised home-based physiotherapy intervention (respiratory, strength, and aerobic)[16]. After a CRC surgery, PT helps you through the recovery process by regaining strength, mobility, and independence. With CRC and chemotherapy/radiation, physical therapy will help maintain hip and spine ROM and strength because they are areas of negative impact for these treatments.

Evidence suggests that physical activity prevents the recurrence of colon cancer and Physical Therapists are able to provide an individualized exercise program based on this evidence with an understanding of the current treatments for cancer and how they affect a person's ability to stay active and exercise.

Read more in the article: Impact of Physical Activity on Cancer Recurrence and Survival in Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer: Findings From CALGB 89803.

Physical therapists also refer to other clinical treatments to help offset side effects of the CRC medical treatment. Some of these treatment strategies include:

Lymphadema Management[edit | edit source]

Some lymph nodes may be removed during surgery and that can interrupt the flow of lymph back to the center of the body. This treatment is used to decrease the swelling caused by this and also the pain and discomfort associated with this problem.

ReBuilder[edit | edit source]

This is a treatment to treat chronic neuropathic pain that is a side effect from CRC chemotherapy. This treatment sends mild electrical pulses to your feet and legs. This treatment helps to reduce this pain so the limbs function better.

Physical therapy is an important piece of treatment to the independence and recovery of patients with CRC. Many times aggressive medical treatment is needed and the patient's independence, strength, range of motion, and fatigue levels are negatively impacted. Physical therapists, with an expertise in this population can have a positive functional impact on their life.[11]

Alternative/Holistic Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Nutrition Therapy[edit | edit source]

There are steps you can take to dramatically reduce your odds of developing colorectal cancer. Researchers estimate that eating a nutritious diet, getting enough exercise, and controlling body fat could prevent 45% of colorectal cancers.

The National Cancer Institute recommends a low-fat diet that includes plenty of fiber and at least five servings of fruits and vegetables per day.

Solid food may not be an option, depending on the stage and treatment.

==Pain management[edit | edit source]

Naturopathic therapy: nontoxic therapy creating a healthy environment inside and out. My include clinical nutrition, botanical medicine, homeopathy, classical Chinese medicine, hydrotherapy, manipulative therapy, environment medicine and minor surgery

Mind Body Medicine[edit | edit source]

Acupuncture:this treatment helps promote the natural healing and functioning of the body. The acupuncturist inserts very small thin needles into points that stimulate energy flow in the body to promote the patient’s immune system.

Auriculotherapy:this treatment is similar to acupuncture but electrical stimulation is used instead of needles. The electrical stimulation is used on specific areas of the ear that correspond to locations on your body.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Colorectal cancer may present and be mistaken as other medical conditions. Some of those are including in the following list and the most common are included in the chart below, with signs and symptoms of the condition, as well as, testing that would be conducted to determine if what the patient is experiencing is colorectal cancer or the differential diagnosis.

- Colon lymphoma

- Colon polyps, benign

- Crohn’s disease

- Diverticular disease

- Gastrointestinal tuberculosis

- Hemorrhoids

- Infectious colitis

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Ischemic colitis

- Ulcerative colitis

| Condition |

Differentiating signs/symptoms |

Differentiating tests |

|---|---|---|

| Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) |

A clinical diagnosis is based on the Rome III Criteria that specify at least 3 months' duration, with onset at least 6 months previously, of recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort associated with 2 or more of: improvement in abdominal pain with defecation, change in frequency of stool, change in form (appearance) of stool. |

• There is no specific diagnostic test for IBS. • Patients who fulfil the clinical criteria for IBS and have no alarm features have a very low probability of organic disease. Colonoscopy or colonic imaging is recommended for patients older than 50 years of age due to higher pre-test probability of colorectal cancer. |

| Ulcerative colitis |

Average age of onset of inflammatory bowel disease (20 to 40 years) is younger than with colorectal cancer. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease frequently have watery diarrhoea. However, patients with colitis are at higher risk of colorectal cancer and may need reassessment if symptoms are atypical or do not respond to treatment. |

• Colonoscopy will show rectal involvement, continuous uniform involvement, loss of vascular marking, diffuse erythema, mucosal granularity, normal terminal ileum (or mild 'backwash' ileitis in pancolitis). |

| Crohn's disease |

Average age of onset of inflammatory bowel disease (20 to 40 years) is younger than with colorectal cancer. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease frequently have watery diarrhoea. Patients with colitis are at higher risk of colorectal cancer and may need reassessment if symptoms are atypical or do not respond to treatment. |

• Colonoscopy with intubation of the ileum is the definitive test to diagnose Crohn's disease and will show mucosal inflammation and discrete deep superficial ulcers located transversely and longitudinally, creating a cobblestone appearance. The lesions are discontinuous, with intermittent areas of normal-appearing bowel (skip lesions). |

| Hemorrhoids |

Causes bright red rectal bleeding that is separate from the stool. There is no abdominal discomfort or pain, altered bowel habits, or weight loss. |

• Colonoscopy or colonic imaging is recommended in patients with abdominal symptoms in addition to rectal bleeding and in those older than 50 years of age. |

| Anal fissure |

Severe pain on defecation. Blood is usually on wiping. There is no abdominal discomfort or pain, altered bowel habits, or weight loss. |

• Colonoscopy or colonic imaging is recommended in patients with abdominal symptoms in addition to rectal bleeding and in those older than 50 years of age. |

| Diverticular disease |

Diverticular stricture or inflammatory mass may be clinically indistinguishable from colorectal cancer. |

• Colonoscopy with biopsies and CT imaging will usually differentiate. |

Case Reports/ Case Studies[edit | edit source]

Case Study #1: From the Cancer Therapy & Supportive Care from John Hopkins Advanced Study in Nursing

• 52yo F presented to her PCP with c/o weakness & fatigue.

• Attributed changes due to menstrual cycle/menopause

• Rapid wt loss of 10lbs with in the past 6 months

PMHx:

• Chronic constipation & hemorrhoids

• Mild dyspnea on exertion

• Chronic arthritis in knees/hands

• No screening for colposcopy or sigmoidscopy

• Not currently receiving hormone therapy, took contraceptives for 10yrs

Family/social Hx:

• Father died age 60 of MI.

• Owns & manages interior design firm

• Divorced, 2 grown children & lives alone

• Active tennis player

Physical examination

• Body type, thing 5’6” 128lbs

• Normal BP, HR, RR

Lab work:

• Found she was anemic and prescribed iron pills

• Anemia was unresolved, she became constipated, denied melena

• Unable to take a stool sample for fecal occult blood testing due to constipation

• Later referred for a colonoscopy which a mass was found (6cm in ascending colon) and a biopsy was taken

• Mass was found to be poorly differentiated invasive adenocarcinoma with ulceration. A CT scan later confirmed the lesion found from the colonoscopy

Treatment:

• With a prior blood transfusion she had a Right hemicoloectomy followed by 6 months of chemo

• Patient was diagnosed with Stage 3C colon cancer

• Issue was resolved and her iron levels were carefully monitored and normalized

Case Study #2: Cardiac metastasis from colorectal cancer: A case report

• 70 yo F presented with bloody stools & admitted to hospital

• Experienced SOB and lost 8.8lbs in the past 3 months

• Colonoscopy showed an adenocarcinoma mass of the sigmoid colon

Lab work:

• All lab work was normal except a routine transthoracic echocardiography showed an enlargement of the right atrium and a mass adjacent to the right atrium.

• A chest x-ray and CT confirmed supporting findings of the echo

Treatment:

• Planned surgery of colon followed by cardiac surgery 4 weeks post

• Anterior Resection with colorectal anastomosis was performed, diagnosed with T4N2 (Stage 3)

• 2wks post op SOB became worse, and immediate cardiac surgery took place

• Mass was removed and identified as adenocarcinoma identical to the one found in the colon.

• Due recurrent cardiac bleeding, pt did not survive treatment 3 days post op

Conclusion:

• Cardiac metastais is more common than what is discovered and documented

• Further evaluation and diagnostic testing due to predicted increase in colorectal cancer metastasizing in the cardiac region is needed.

Case Study #3: Colonic Carcinoma in a Young Adult Presenting as an Intussusception

- 32 yo F presented with a 15 day history of intermittent abdominal pain and nausea

- One episode of diarrhea with no blood or mucus

- initial examination revealed diffuse tenderness in the epigastrium and left upper quadrant

Lab Work:

- Patient developed tachycardia and pain that had to be controlled with analgesia

- Patient had developed anemia

- Ultrasound scan was unremarkable

- CT scan suggested a large bowel intussesception with a probable mass lesion

Treatment:

- An extended right hemicolectomy was performed

- Histology revealed an intussusception around a tubulovillous adenoma with moderately differentiated adencarcinomatous changes

- She was discharged without complications 10 days after surgery

Conclusion:

- Clinical presentation may include a palpable mass, nausea and vomiting, abdominal colic, change in bowel habit and occult blood per rectum.

- It is important during a patient's initial visit to ask challenging questions if they present with an abnormal presentation.

- Early referral for these patients is critical because this cancer is repidly progressive.

- MD's in this report that though this women was referred and diagnosed quickl, she would have benefited more had she been diagnosed even quicker.

- A high index of suspicion and an early CT scan may prevent delayed diagnosis and the development of complications.

Resources[edit | edit source]

Cancer Treatment Centers of America

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Colorectal cancer Available from:https://www.nfcr.org/blog/blog9-must-know-facts-colorectal-cancer/ (30.8.2020)

- ↑ National foundation for cancer research Colorectal cancer Available from:https://www.nfcr.org/blog/blog9-must-know-facts-colorectal-cancer/ (last accessed 29.8.2020)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Nakayama G, Tanaka C, Kodera Y. Current options for the diagnosis, staging and therapeutic management of colorectal cancer. Gastrointestinal tumors. 2014;1(1):25-32.Available from:https://www.karger.com/Article/Fulltext/354995 (last accessed 30.8.2020)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Colorectal Cancer Overview [Internet]. American Cancer Society. 2013 [updated 2013 Jan 17]. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/cancer/colonandrectumcancer/overviewguide/colorectal-cancer-overview-key-statistics.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Seer Stat Facts Sheets: Colon and Rectum [Internet]. National Cancer Institute. 2012 [updated 2011 Nov]. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html.

- ↑ Enzinger PC, Benson AB, Mitchell EP, et al. Medical Update on Colorectal Cancer Understanding KRAS [pamphlet]. New York: Elsevier Oncology; 2010.

- ↑ Colorectal (Colon) Cancer [Internet]. Center for Disease Control. 2012 [updated 2012 Oct 22]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/index.htm.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Tidy, Colin MD. Colorectal Cancer [Internet]. Patient.co.uk; 2012 [updated 2012 July 19]. Available from: http://www.patient.co.uk/doctor/colorectal-adenocarcinoma.htm.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Oruç Z, Kaplan MA. Effect of exercise on colorectal cancer prevention and treatment. World journal of gastrointestinal oncology. 2019 May 15;11(5):348.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6522766/ (last accessed 30.8.2020)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Radiopedia CRC Available from:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/colorectal-carcinoma ( last accessed 30.8.2020)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Colorectal Cancer: Integrative Treatment Program [Internet]. Cancer Treatment Centers of America. 2012. Available from: http://www.cancercenter.com/colorectal-cancer.cfm.

- ↑ De Marco MF, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Van Der Heijden LH, et al. Comorbidity and colorectal cancer according to subsite and stage: a population-based study. Eur J Cancer. 2000 Jan; 36(1): 95-9

- ↑ Cancernet CRC Available from:https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/colorectal-cancer/diagnosis (last accessed 30.8.2020)

- ↑ Cruz-Fernández M, Achalandabaso-Ochoa A, Gallart-Aragón T, Artacho-Cordón F, Cabrerizo-Fernández MJ, Pacce-Bedetti N, Cantarero-Villanueva I. Quantity and quality of muscle in patients recently diagnosed with colorectal cancer: a comparison with cancer-free controls. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2020 Jan 22:1-8.

- ↑ http://cedarhillpt.com/2010/01/stretch-yourself-a-2010-challenge-from-cedar-hill/clipart-illustration-of-an-orange-man-sitting-on-a-gym-floor-and/

- ↑ Karlsson E, Farahnak P, Franzen E, Nygren-Bonnier M, Dronkers J, van Meeteren N, Rydwik E. Feasibility of preoperative supervised home-based exercise in older adults undergoing colorectal cancer surgery–A randomized controlled design. PloS one. 2019;14(7).

- ↑ Colorectal Cancer [Internet]. BMJ Publishing Group. 2011 [updated 2013 Feb 4]. Available from: http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/monograph/258/diagnosis/differential.html.