Cesarean Section: Difference between revisions

(Functional re-training section was added (combining some of the other PT management sections)) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 162: | Line 162: | ||

It is known that there is an increased likelihood of the development of diastasis recti abdominis (DRA) during pregnancy and following abdominal surgery. Please follow to this link on the condition: [[Diastasis recti abdominis|Physiopedia page on DRA.]] As well, see the exercise section for core training. | It is known that there is an increased likelihood of the development of diastasis recti abdominis (DRA) during pregnancy and following abdominal surgery. Please follow to this link on the condition: [[Diastasis recti abdominis|Physiopedia page on DRA.]] As well, see the exercise section for core training. | ||

It is also important to consider the symptoms that arise during pregnancy. Back pain is common and can result in functional limitations.<ref>MacEvilly M, Buggy D. Back pain and pregnancy: a review. Pain. 1996 Mar 1;64(3):405-14.</ref><ref>Liddle SD, Pennick V. Interventions for preventing and treating low‐back and pelvic pain during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015(9).</ref> Okanishi and colleagues<ref>Okanishi N, Kito N, Akiyama M, Yamamoto M. Spinal curvature and characteristics of postural change in pregnant women. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2012 Jul;91(7):856-61.</ref> also found that a decrease in muscle tone during pregnancy may contribute to poor posture. Additionally, the diaphragm must also elevate during pregnancy while the fetus is developing, which may lead to dyspnea.<ref>Stephenson RG, O'Connor LJ. Obstetric and gynecologic care in physical therapy. Slack Incorporated; 2000.</ref> Furthermore, exercises for pelvic pain,<ref>Vleeming A, Albert HB, Östgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. European Spine Journal. 2008 Jun 1;17(6):794-819.</ref> body mechanics, postural correction, and breathing may be of benefit. | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

Revision as of 17:36, 12 June 2020

Definition[edit | edit source]

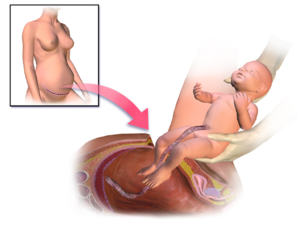

- A cesarean section can be defined as the procedure in which the delivery of a baby is through an incision in the abdominal wall and uterus rather than through the pelvis and vagina.[2][3][4][5][6] General, spinal or epidural anesthesia is used.[7]

- In a cesarean delivery, an incision is made in the lower abdominal wall and in the uterus.The incision can be vertical or transverse. However, the condition of the mother and the fetus determines which type of incision has to be used.

Transverse Incision[edit | edit source]

- Its extension lies across the pubic hairline.

- It is most commonly used because it heals faster and there is minimal bleeding.

- It also increases the chance for normal delivery in future pregnancies.

Vertical Incision[edit | edit source]

Its extension is from navel to pubic hairline.

Reasons for the Procedure[edit | edit source]

Some cesarean deliveries are planned and scheduled, while others are performed as a result of complication that occurs during the labour. There are several conditions in which cesarean delivery is more likely to occur. These include:

- Fetal distress which is indicated by abnormal fetal heart rate.

- Abnormal position of the fetus during birth like breech presentation etc.

- Slow-moving labor that fails to progress normally.

- Size of a baby is too large to be delivered vaginally.

- Placental complications like placenta previa.

- Maternal medical conditions such as diabetes, high blood pressure, HIV infection, etc.

- Active herpes infection in the mother’s vagina or cervix.

- Twins or multiple fetus.

- Previous history of cesarean delivery.[8][9] Initially, clinicians were concerned about the scar from the previous birth rupturing. However, growing evidence is supporting safe vaginal birth after caesarean (VBAC).[10][11][12][13]

Procedure[edit | edit source]

Preoperative Preparation[edit | edit source]

Informed written permission from the patient for the procedure,anesthesia and blood transfusion is obtained.

- Abdomen is scrubbed with soap and nonorganic iodide lotion. Hair is usually clipped.

- Premedication sedatives should not be given.

- Nonparticulate antacid (0.3 molar sodium citrate, 30 ml) is given orally before transferring the patient to the operation theatre. This is given to neutralize the existing gastric acid.

- Ranitidine 150 mg is usually given orally night before and it is repeated 1 hour before the surgery to raise the gastric pH.

- The stomach should be emptied , If needed,it can be emptied by a stomach tube also.

- Metoclopramide (10 mg) is given to increase the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter as well as to reduce the stomach contents. It is administered after 3 minutes of preoxygenation in the operation theatre.

- Bladder has to be emptied by a Foley catheter which is kept in place in the perioperative period.

- Fetal heart sound should be evaluated again at this stage.

- Neonatologist should be available at this stage.

- Cross-match blood when above-average blood loss (placenta previa, prior multiple cesarean delivery) is expected.

- Prophylactic antibiotics should be given (IV) before cesarean section.

Important Consideration:[edit | edit source]

IV cannula: Placed to administer fluids.

Procedure[edit | edit source]

Position of the patient: The patient should be placed in the dorsal position. In susceptible cases, to minimize any harmful effects of venacaval compression, a 15 degree tilt to her left using a wedge till delivery of the baby should be done.

Anesthesia- It can be spinal, epidural or general. However, the choice of the patient and the urgency of delivery is also considered.

Antiseptic painting-The abdomen should be painted with 7.5% povidone-iodine solution or savlon lotion and should be properly draped with sterile towels.

Incision on the abdomen.

Packing:The Doyen’s retractor is introduced in this stage.

Uterine incision.

Delivery of head:

The membranes are ruptured if it is still intact. The blood mixed amniotic fluid is sucked out by continuous suction. The Doyen’s retractor is removed. The head is delivered by hooking the head with the fingers which are carefully insinuated between the lower uterine flap and the head until the palm is placed below the head. The head is delivered by elevation and flexion using the palm to act as fulcrum. As the head is drawn to incision line, the assistant is to apply pressure on the fundus. If the head is jammed, an assistant may push up the head by sterile gloved fingers introduced into the vagina. The head can also be delivered using either Wringley’s or Barton’s forceps. Delivery of the trunk: As soon as the head is delivered, the mucus from the mouth, pharynx and nostrils is sucked out using rubber catheter attached to an electric suction machine. After the delivery of the shoulders, intravenous oxytocin 20 units or methergine 0.2 mg has to be administered. The rest of the body should be delivered slowly and the baby should be placed in a tray placed in between the mother’s thighs with the head tilted down for gravitational drainage. The cord should be cut in between two clamps and the baby should be handed over to the paediatrician. The Doyen’s retractor is reintroduced. The optimum interval between uterine incision and delivery should be less than 90 seconds.

Removal of the placenta and membranes:

By this time, the placenta is separated spontaneously. The placenta has to be extracted by traction on the cord with simultaneous pushing of the uterus towards the umbilicus per abdomen using the left hand(controlled cord traction). Routine manual removal should not be done. Dilation of internal os is not required. Exploration of the uterine cavity is desirable.

Suture of the uterine wound.

Non closure of visceral and parietal peritoneum is preferred .

Concluding Part:

The mops placed inside are removed and the number is checked.Peritoneal toileting should be done and blood clots are to be removed carefully and precisely.The tubes and ovaries are examined.Doyen’s retractor is removed.After being satisfied the uterus is well contracted, the abdomen is closed in layers.The vagina is cleansed of blood clots and a sterile vulval pad is placed.[14]

Potential Structural and Functional Impairments:[edit | edit source]

- There is a risk of pulmonary, gastrointestinal or vascular complications.

- Post surgical pain and discomfort is common.

- Development and adhesions at incision site is seen.

- Faulty posture is commonly observed.

- Pelvic floor dysfunction which presents as:

- Urinary or fecal incontinence

- Organ prolapse

- Hypertonus

- Poor proprioceptive awareness and disuse atrophy

- Abdominal weakness,diastasis recti can occur.

- General functional restrictions is seen post delivery.

Significance to Physical Therapists[edit | edit source]

Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Women who have had a cesarean delivery may still require pelvic floor rehabilitation. Many women experience lengthy labor, including prolonged second stage (pushing), before a cesarean section is considered necessary. Therefore, pelvic floor musculature and pudendal and levator ani nerves function may still be compromised. Also, pregnancy itself creates a significant strain on pelvic floor musculature and other soft tissues.

Post Surgical Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Postpartum intervention for the woman who had a cesarean delivery is similar to that of the woman who has had a vaginal delivery. However, a cesarean section is major abdominal surgery with all the complications of such surgeries and therefore the woman will also require general post-surgical rehabilitation.

Physiotherapy Management after Caesarean Section[edit | edit source]

Reduce risk of pulmonary complications[edit | edit source]

A study by Karakaya and colleagues[15] looking at the effectiveness of a physiotherapy program on pain and function acutely after a caesarean section incorporated thoracic expansion and huffing as respiratory treatment techniques. However, since the program consisted of numerous components it is difficult to determine the specific effect of these techniques. Additionally, Kaplan and colleagues[16] found no benefit to respiratory therapy after caesarean sections with transverse incisions and a systematic review by Pasquina and colleagues[17] concluded that available evidence is older and has limitations, so it is not enough to justify the routine use of respiratory physiotherapy after various abdominal surgeries. Morran and colleagues[18] found that deep breathing, cough, and postural drainage reduced the incidence of pneumonia in high-risk patients but 2 other studies found, while not statistically significant, an increase in the incidence of pneumonia after those interventions.[19][20] Two other studies have supported the use of deep breathing, directed cough and postural drainage to reduce the incidence of atelectasis.[21][22]

More recently, the postoperative period has been found to put patients at an increased risk of pulmonary complications. [23] Patients seem to have decreased peak cough flow after upper abdominal surgery secondary to postoperative restrictive lung dysfunction.[24] To help mobilize secretions and maximize cough effectiveness, especially in high-risk patients, thoracic expansion/deep breathing will allow for lung inflation and gas exchange and huffing and splinting a cough will provide a less painful alternative.

[edit | edit source]

The same study mentioned previously by Karakaya and colleagues[15] also included transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS). The TENS pads were placed on either side of the incision and it was set to the following parameters: frequency of 120 Hz, pulse width of 60 us, and intensity evoking a strong tingling sensation for 30 minutes.[15] The researchers found that pain and difficulty performing functional activities decreased significantly as measured by visual analogue scales at rest and during movement.[15] This study supports other studies that have indicated TENS to be effective in decreasing post-caesarean incisional pain.[25][26][27][28] A meta-analysis calculated the mean formation rate of adhesions to be 41% amongst women undergoing caesarean section procedures.[29] To add, postoperative adhesions have been found to be a culprit in chronic pain.[29][30] Nonsurgical management has included various soft tissue interventions. Wasserman and colleagues[31] performed scar massage techniques, pelvic and abdominal diaphragm myofascial release, and mobilizations to visceral structures on 2 women who had chronic pain for 6-9 years after their caesarean sections. Results showed an increase in pressure tolerance and scar mobility and improvement in overall pain as measured by a Pressure Algometer, Adheremeter, and Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS).[31] Comesana and colleagues[32] performed myofascial induction therapy sessions on 10 women with caesarean section scars older than 1.5 years. Results were similar, in that they showed improved structure of the scar and improved function and quality of life as measured by ultrasound, Schober’s Test, and the 36-Item Short Form Survey.[32] A randomized controlled trial was done more recently by Wasserman and colleagues.[33] Participants were split into 2 groups receiving 4 treatments total. Group 1 received superficial massage and scar rolling; Group 2 received the same treatment in addition to abdominal myofascial release and deep scar mobilization.[33] Results for both groups showed significant improvements in pain, pressure pain threshold, scar mobility, and the Oswestry Disability Index.[33] Furthermore, this study supports the effectiveness of deep and superficial interventions.

To prevent post surgical vascular or gastrointestinal complications.[edit | edit source]

- Active leg exercises should be taught.

- Early ambulation should be encouraged.

- Abdominal massage to peristalsis can be taught.

To enhance incisional circulation[edit | edit source]

- Gentle abdominal exercise with incisional support should be taught.

- scar mobilisation can be done.

- friction massage can be given.

To decrease post-surgical discomfort from flatulence, itching or catheter.[edit | edit source]

- Instructions regarding positioning should be given.

- massage can be given.

- supportive exercises can be taught.

Functional re-training[edit | edit source]

Lower extremity exercises have been linked to earlier mobilization and decreased pain.[15] Studies support early mobilization, sometime between 6 and 24 hours post-operatively, to improve pulmonary function, reduce risk of embolism, and decrease length of hospital stay.[34][35][36]

In their study, Karakaya and colleagues[15] also incorporated exercises to retrain posture. Study participants performed 5-10 repetitions, 3x/day, especially after breast feeding. They were also encouraged to contract their pelvic floor during activities that required an increase in intra-abdominal pressure.[15] Unfortunately, they did not investigate the effects of these interventions because there was no long-term follow-up. Some evidence has found that there is actually a higher incidence of pelvic floor muscle dysfunction following a vaginal birth[37][38] but other studies have not shown significant difference in the incidence following a vaginal or caesarean birth.[39][40]

A study by Gursen and colleagues[41] looked at the effects of Kinesio taping (KT) combined with exercise compared to exercise alone on abdominal rehabilitation after caesarean sections. KT application on the rectus abdominal muscles, oblique abdominal muscles and caesarean incision 2x/week for 4 weeks lead to more significant improvements in abdominal strength, pain, and self-reported disability as measured by manual muscle testing and sit-up tests, the Visual Analog Scale, and the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire.[42]

It is known that there is an increased likelihood of the development of diastasis recti abdominis (DRA) during pregnancy and following abdominal surgery. Please follow to this link on the condition: Physiopedia page on DRA. As well, see the exercise section for core training.

It is also important to consider the symptoms that arise during pregnancy. Back pain is common and can result in functional limitations.[43][44] Okanishi and colleagues[45] also found that a decrease in muscle tone during pregnancy may contribute to poor posture. Additionally, the diaphragm must also elevate during pregnancy while the fetus is developing, which may lead to dyspnea.[46] Furthermore, exercises for pelvic pain,[47] body mechanics, postural correction, and breathing may be of benefit.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Blausen.com staff (2014). "Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014". WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436. [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]

- ↑ Al-Ziraqi, I, et al: uterine rupture after previous caesarean section.BJOG 117(7):809-820,2010

- ↑ Gilbert,E, and Harman, J;High risk pregnancy and delivery, ed.1.St Louis:CV Mosby,1986

- ↑ Harrington,K, and Haskvitz, E:Managing a patient’s constipation with physical therapy.Phys Ther Nov 86:1511-1519;2006

- ↑ Jamieson,D, and Steege, J:The prevalence of dysmenorrhea,dyspareunia, pelvic pain and irritable bowel syndrome in primary care practices.Obstet Gynecol 87(1):55-58,1996

- ↑ Norwood,C:caesarean variations: Patients, facilities, or policies.Int J Childbirth Educ 1 :4,1986.

- ↑ Carolyn Kisner, Lynn Allen Colby :Therapeutic Exercise Foundations and techniques 6 th edition:Pg 952

- ↑ Pushpal K Mitra : Textbook of Physiotherapy in surgical conditions:Pg 235-238

- ↑ Notzon FC, Cnattingius S, Bergsjø P, Cole S, Taffel S, Irgens L, Daltveit AK. Cesarean section delivery in the 1980's: International comparison by indication. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1994 Feb 1;170(2):495-504.

- ↑ Bangal VB, Giri PA, Shinde KK, Gavhane SP. Vaginal birth after cesarean section. North American journal of medical sciences. 2013 Feb;5(2):140.

- ↑ Cahill A, Tuuli M, Odibo AO, Stamilio DM, Macones GA. Vaginal birth after caesarean for women with three or more prior caesareans: assessing safety and success. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2010 Mar;117(4):422-8.

- ↑ Flamm BL, Goings JR, Liu Y et al. Elective repeat caesarean section versus trial of labour: a prospective multicenter study. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1994; 83: 927-932.

- ↑ McMahon MJ, Luther ER, Bowes WA et al. Comparison of trial of labour with an elective second caesarean section. New England Journal of Medicine 1996; 335: 689-695.

- ↑ Hiralal Konar:DC Dutta’s textbook of obstetrics 8 th edition:Pg 671

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 Karakaya İÇ, Yüksel İ, Akbayrak T, Demirtürk F, Karakaya MG, Özyüncü Ö, Beksaç S. Effects of physiotherapy on pain and functional activities after cesarean delivery. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics. 2012 Mar 1;285(3):621-7.

- ↑ Kaplan B, Rabinerson D, Neri A. The effect of respiratory physiotherapy on the pulmonary function of women following cesarean section under general anesthesia. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 1994 Nov;47(2):177.

- ↑ Pasquina P, Tramer MR, Granier JM, Walder B. Respiratory physiotherapy to prevent pulmonary complications after abdominal surgery: a systematic review. Chest. 2006 Dec 1;130(6):1887-99.

- ↑ Morran CG, FLNLAY I, Mathieson M, McKay AJ, Wilson N, McArdle CS. Randomized controlled trial of physiotherapy for postoperative pulmonary complications. BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1983 Nov 1;55(11):1113-7.

- ↑ Hallböök T, Lindblad B, Lindroth B, Wolff T. Prophylaxis against pulmonary complications in patients undergoing gall-bladder surgery. A comparison between early mobilization, physiotherapy with and without bronchodilatation. InAnnales Chirurgiae et gynaecologiae 1984 (Vol. 73, No. 2, pp. 55-58).

- ↑ Mackay MR, Ellis E, Johnston C. Randomised clinical trial of physiotherapy after open abdominal surgery in high risk patients. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 2005 Jan 1;51(3):151-9.

- ↑ Chumillas S, Ponce J, Delgado F, Viciano V, Mateu M. Prevention of postoperative pulmonary complications through respiratory rehabilitation: a controlled clinical study. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1998 Jan 1;79(1):5-9.

- ↑ WIKLANDER O, NORLIN U, PATTERSON RL. EFFECT OF PHYSIOTHERAPY ON POSTOPERATIVE PULMONARY COMPLICATIONS A CLINICAL AND ROENTGENOGRAPHIC STUDY OF 200 CASES. Survey of Anesthesiology. 1958 Feb 1;2(1):97.

- ↑ Silva DR, Gazzana MB, Knorst MM. Merit of preoperative clinical findings and functional pulmonary evaluation as predictors of postoperative pulmonary complications. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2010 Jan 1;56(5):551-7.

- ↑ Colucci DB, Fiore JF, Paisani DM, Risso TT, Colucci M, Chiavegato LD, Faresin SM. Cough impairment and risk of postoperative pulmonary complications after open upper abdominal surgery. Respiratory care. 2015 May 1;60(5):673-8.

- ↑ Hollinger JL. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation after cesarean birth. Physical therapy. 1986 Jan 1;66(1):36-8.

- ↑ Kayman-Kose S, Arioz DT, Toktas H, Koken G, Kanat-Pektas M, Kose M, Yilmazer M. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for pain control after vaginal delivery and cesarean section. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2014 Oct 1;27(15):1572-5.

- ↑ Navarro CN, Pacheco MC. Transcutaneous electric stimulation (TENS) to reduce pain after cesarean section. Ginecologia y obstetricia de Mexico. 2000 Feb;68:60-3.

- ↑ Smith CM, Guralnick MS, Gelfand MM, Jeans ME. The effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on post-cesarean pain. Pain. 1986 Nov 1;27(2):181-93.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Okabayashi K, Ashrafian H, Zacharakis E, Hasegawa H, Kitagawa Y, Athanasiou T, Darzi A. Adhesions after abdominal surgery: a systematic review of the incidence, distribution and severity. Surgery today. 2014 Mar 1;44(3):405-20.

- ↑ Nikolajsen L, Sørensen HC, Jensen TS, Kehlet H. Chronic pain following Caesarean section. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2004 Jan;48(1):111-6.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Wasserman JB, Steele-Thornborrow JL, Yuen JS, Halkiotis M, Riggins EM. Chronic caesarian section scar pain treated with fascial scar release techniques: A case series. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies. 2016 Oct 1;20(4):906-13.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Comesaña AC, Vicente MD, Ferreira TD, del Mar Pérez-La Fuente M, Quintáns MM, Pilat A. Effect of myofascial induction therapy on post-c-section scars, more than one and a half years old. Pilot study. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies. 2017 Jan 1;21(1):197-204.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Wasserman JB, Abraham K, Massery M, Chu J, Farrow A, Marcoux BC. Soft Tissue Mobilization Techniques Are Effective in Treating Chronic Pain Following Cesarean Section: A Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy. 2018 Sep 1;42(3):111-9.

- ↑ Jacobsen AF, Skjeldestad FE, Sandset PM. Ante‐and postnatal risk factors of venous thrombosis: a hospital‐based case–control study. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis. 2008 Jun;6(6):905-12.

- ↑ Liu S, Liston RM, Joseph KS, Heaman M, Sauve R, Kramer MS. Maternal mortality and severe morbidity associated with low-risk planned cesarean delivery versus planned vaginal delivery at term. Cmaj. 2007 Feb 13;176(4):455-60.

- ↑ Deniau B, Bouhadjari N, Faitot V, Mortazavi A, Kayem G, Mandelbrot L, Keita H. Evaluation of a continuous improvement programme of enhanced recovery after caesarean delivery under neuraxial anaesthesia. Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain Medicine. 2016 Dec 1;35(6):395-9.

- ↑ Bortolini MA, Drutz HP, Lovatsis D, Alarab M. Vaginal delivery and pelvic floor dysfunction: current evidence and implications for future research. International urogynecology journal. 2010 Aug 1;21(8):1025-30.

- ↑ de Souza Caroci A, Riesco ML, Da Silva Sousa W, Cotrim AC, Sena EM, Rocha NL, Fontes CN. Analysis of pelvic floor musculature function during pregnancy and postpartum: a cohort study: (A prospective cohort study to assess the PFMS by perineometry and digital vaginal palpation during pregnancy and following vaginal or caesarean childbirth). Journal of clinical nursing. 2010 Sep;19(17‐18):2424-33.

- ↑ Barbosa AM, Marini G, Piculo F, Rudge CV, Calderon IM, Rudge MV. Prevalence of urinary incontinence and pelvic floor muscle dysfunction in primiparae two years after cesarean section: cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Medical Journal. 2013;131(2):95-9.

- ↑ Hilde G, Stær-Jensen J, Siafarikas F, Engh ME, Brækken IH, Bø K. Impact of childbirth and mode of delivery on vaginal resting pressure and on pelvic floor muscle strength and endurance. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2013 Jan 1;208(1):50-e1.

- ↑ Gürşen C, İnanoğlu D, Kaya S, Akbayrak T, Baltacı G. Effects of exercise and Kinesio taping on abdominal recovery in women with cesarean section: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics. 2016 Mar 1;293(3):557-65.

- ↑ Gürşen C, İnanoğlu D, Kaya S, Akbayrak T, Baltacı G. Effects of exercise and Kinesio taping on abdominal recovery in women with cesarean section: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics. 2016 Mar 1;293(3):557-65.

- ↑ MacEvilly M, Buggy D. Back pain and pregnancy: a review. Pain. 1996 Mar 1;64(3):405-14.

- ↑ Liddle SD, Pennick V. Interventions for preventing and treating low‐back and pelvic pain during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015(9).

- ↑ Okanishi N, Kito N, Akiyama M, Yamamoto M. Spinal curvature and characteristics of postural change in pregnant women. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2012 Jul;91(7):856-61.

- ↑ Stephenson RG, O'Connor LJ. Obstetric and gynecologic care in physical therapy. Slack Incorporated; 2000.

- ↑ Vleeming A, Albert HB, Östgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. European Spine Journal. 2008 Jun 1;17(6):794-819.