Cervical Osteoarthritis

Original Editors - Bram Sorel

Top Contributors - Lisa Pernet, Sheik Abdul Khadir, Nina Myburg, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Kenneth de Becker, Scott Cornish, Jason Coldwell, Admin, Bram Sorel, Evan Thomas, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Nicolas Casier, WikiSysop, Rucha Gadgil, Jess Bell and Olajumoke Ogunleye

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

Keywords: Cervical osteoarthritis, physical therapy, prevalence, facet-joint osteoarthritis, rehabilitation, physiotherapy, neck exercises, arthrosis

Databases: PubMed, Pedro, Web of Knowledge, Cochrane Library, Library of the VUB, Medscape

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

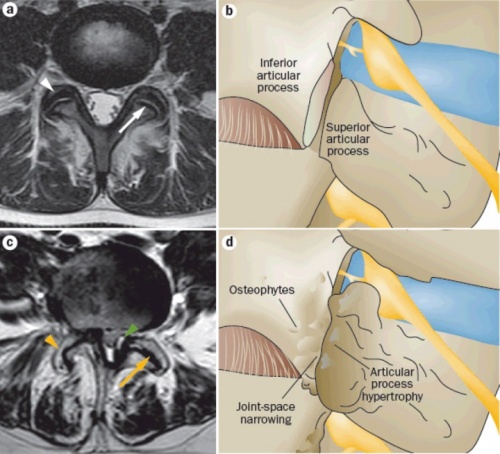

Cervical osteoarthritis may be defined as a degenerative disorder of the synovial facet joints [1], which are located in the posterior aspect of the vertebral column and, in humans, are the only true synovial joints between adjacent spinal levels. Facet joint osteoarthritis (FJ OA) is widely prevalent in older adults, and is thought to be a common cause of back and neck pain.

The disorder is associated with loss of hyaline cartilage, remodeling of underlying bone, formation of osteophytes at the joint margins and thickening of the joint capsule [1] [2].The process of failure also involves ligaments, periarticular paraspinal muscles and soft tissues [3]. At the level of the cervical spine, the synovial joint, otherwise known as the zygapophyseal joints are mainly affected by OA.

Although cervical osteoarthritis is often referred to as cervical spondylosis [4], it is not clear whether these two concepts may be considered synonyms.

Risk factors for OA[3]

• Age

• Sex

• Overweight

• Physical trauma

• Occupational factors

• Smoking

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

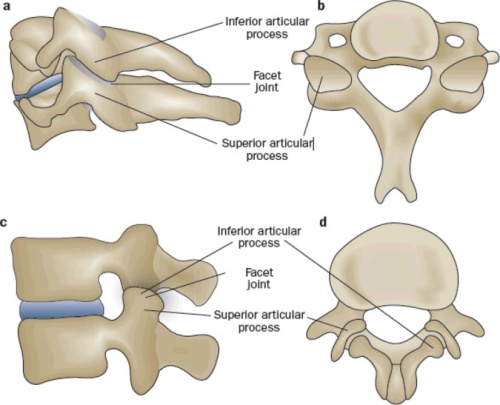

We speak off a “three-joint complex” at every spinal level except C1–C2. This motion segment, is formed by the three articulations between adjacent vertebrae. This three articulations consist of one disc and two facet joints. The superior articular processes of the lower vertebra is positioned upwards and will articulate with the smaller inferior articular processes of the vertebra above it. The cervical facet articular surface area is about two-thirds the size of the area of the vertebral end plate. The facet joint exhibits features typical of synovial joints: articular cartilage covers the opposed surfaces of each of the facets, resting on a thickened layer of subchondral bone, and a synovial membrane bridges the margins of the cartilaginous portions of the joint. A superior and inferior capsular pouch, filled with fat, is formed at the poles of the joint, and a baggy fibrous joint capsule covers the joint like a hood. A fibroadipose meniscoid projects into the superior and inferior aspect of the joint and consists of a fold of synovium that encloses fat, collagen, and blood vessels. These meniscoids serve to increase the contact surface area when the facets are brought into contact with one another during motion, and slide during flexion of the joint to cover articular surfaces exposed by this movement. [3]

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

Cervical osteoarthritis may be generalized, sometimes involving the entire cervical region, but it is usually more localized between the fifth and sixth and sixth and seventh cervical vertebrae.

Everyone can have cervical osteoarthritis but it is rare in people younger than 40-50 years, the incidence increases with age [1] [2]. Also women have a higher risk for cervical OA than men [1] [5]. It is rather common in people above the age of 50 and especially if those people had jobs that included staying in one position during a long period of time e.g. reading, writing and other table works.

The occurrence of cervical OA can have many causes. E.g. mechanically overstressing a joint (e.g. working with tools that generate intense vibration), past bone fractures or other injuries to the neck, overload at young age, posture asymmetry or asymmetric loading of a joint,… . A relation has been shown between the severity of the complaints of cervical osteoarthritis and a higher body weight of the patient [6].

Facet joint osteoarthritis (FJ OA) is intimately linked to the distinct but functionally related condition of degenerative disc disease, which affects structures in the anterior aspect of the vertebral column. FJ OA and degenerative disc disease are both thought to be common causes of back and neck pain, which in turn have an enormous impact on the health-care systems and economies of developed countries [3].

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

OA is characterised by pain, stiffness, crepitus, limited range of movement and sometimes also joint instability and mild synovitis [1] [7] [8]. The pain is usually localized around the affected joint , but at the level of the spine referred pain may occur. For the cervical spine, pain associated with FJ OA can arise from nociceptors within and surrounding the joints, including nociceptors in the bone itself. The facet joints and their capsules are well innervated[3]. The pain radiates to the occiput, the medial border of the scapula and the upper limbs [7]. Pain often worsens with joint use and is more severe at the end of the day. If there is morning stiffness, it usually lasts less than 30 minutes [1]. Restricted movement can occur due to pain, capsular thickening and the presence of osteophytes [1].

Pressure symptoms in the cervical spine are caused by Osteoarthritis of the uncovertebral joints. Osteophytes can form around the intevertbral joints and cause neurological symptoms due to compression of the spinal nerves [4]. Narrowing of the spinal canal can also cause circulation problems. Performing an MRI can be useful to confirm the presence of compression of the spinal cord.

Prolonged peripheral inflammation in and around facet joints can lead to central sensitization, neuronal plasticity, and the development of chronic spinal pain[3]. The therapist must remain alert to several key characters, also called red flags, as this may indicate a more serious problem [7]:

- Malignancy, infection, or inflammation

- Fever, night sweats

- Unexpected weight loss

- History of inflammatory arthritis, infection, tuberculosis, HIV infection, drug dependency, or immunosuppression

- Excruciating pain

- Intractable night pain

- Cervical lymphadenopathy

- Exquisite tenderness over a vertebral body

- Myelopathy

- Gait disturbance or clumsy hands, or both

- Objective neurological deficit

- Sudden onset in a young patient suggests disc prolapse

- History of severe osteoporosis

- Drop attacks, especially when moving the neck, suggest vascular disease

- Intractable or increasing pain

Differential Diagnosis [1] [7]

[edit | edit source]

- Other non-specific neck pain lesions: acute neck strain, postural neck ache, or whiplash

- Fibromyalgia and psychogenic neck pain

- Mechanical lesions: disc prolapse

- Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

- Inflammatory disease: rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, polymyalgia rheumatica, psoriatric arthritis, septic arthritis, reactive arthritis

- Metabolic diseases: Paget’s disease, osteoporosis, gout, or pseudo-gout

- Osteomyelitis or tuberculosis

- Malignancy: primary tumors, secondary deposits, or myeloma

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis is usually based on the clinical presentation [8][9].

• Pain on range of motion

• Limitation of range of motion

• Lower extremity sensory loss, reflex loss, motor weakness caused by nerve root impingement

• Pseudoclaudication caused by spinal stenosis

Radiology can also be used to determine OA, but one must take into account that people with radiological signs can remain asymptomatic [1]. Kellgren and Lawrence developed a grading system for the radiological appearance of a joint with osteoarthritis [4].

| Radiological appearance of osteoarthritis | Grade |

|---|---|

| normal (no signs of osteoarthritis) | 0 |

| doubtful change (uncertain) | 1 |

| definite, minimal to mild | 2 |

| definite, moderate | 3 |

| definite, severe | 4 |

If more than one joint in a group is assessed, then the most severe grade is reported.

Parameters:

- osteophytes at the joint margins and periarticular ossicles

- narrowing of the joint space

- cystic areas with sclerotic walls in subchondral bone

- deformity of bone (altered shape)

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Functional status and disability measure (evaluation of the activities of daily living) can be assessed by the “Neck Pain and Disability Scale” [7].

Examination[edit | edit source]

Because osteoarthritis is primarily a clinical diagnosis, physicians can confidently make the diagnosis based on the history and physical examination. Most patients with osteoarthritis of the neck will complain about joint pain in this area. The pain tends to worsen with activity, especially following a period of rest (gelling phenomenon). Besides pain on range of motion patients will have a limited range of motion[9].

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Surgical treatment

There are indications that excision and fusion of the anterior cervical intervertebral disc (Cloward operation) together with the removal of associated arthritic bone spurs pressing on the nerves and spinal cord can give relief of pain and muscle weakness in patients who have cervical osteoarthritis with neurologic pain [10].

Transarticular screw fixation

Patients with atlantoaxial (C1-C2) facet joint osteoarthritis have a positive reaction on pain after the fusion of these two facet joints. This treatment has a relative low rate of serious complications [11].

Laminoplasty

Laminoplasty is used to decompress the cervical spinal cord. A risk of this surgical treatment is a reduced strength and shear stiffness (SS) of motion segments. As a result of this, the patient can suffer from instability. Also a great part of the patients had neck pain after the surgical the method of Kuang-Ting Yeh choses laminoplasty instead of laminectomy as a decompression method in posterior instrumented fusion for degenerative cervical kyphosis with stenosis [12]. In short-terms there are some benefits from chondroitin (alone or in combination with glucosamine). Benefits are small to moderate but clinically meaningful [13].

Intra-articular corticosteroids are recommended for hip and knee osteoarthritis. The effects of corticosteroids on cervical osteoarthritis need to be researched [14] [15] [16] [17].

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

The main goals of management for cervical OA [1] (LoE: 1A) are:

• reducing pain and stiffness

• improving joint mobility

• inhibiting further progression of joint damage

The treatment for cervical osteoarthritis is usually conservative and it can be treated using a variety of therapy possibility.

The possibilities for therapy are:

• Heat and cold modalities

Various physiotherapy modalities can be used to reduce pain. Even though there is a lack of evidence for the application of local heat or cold, it is often used by patients with OA to decrease pain.

• Manipulative therapy

• Hydrotherapy

• Postural awareness

• Relaxation

• Cervical traction

• Neck support

• Electromagnetic fields for the treatment of osteoarthritis.

• Pulsed electric stimulation

Pulsed electric stimulation as a treatment for osteoarthritis, is a promising treatment because it has shown the stimulation of cartilage growth at the cellular level. On the other end there is an urgent need for further large-scale studies of pulsed electric stimulation to confirm these finding for purposes concerning the medical sector [18]. There is also research into new methods to use in the treatment of OA to reduce pain. It is thought that magnetic therapy represents an alternative therapy for patients suffering from cervical OA. Electromagnetic fields can be applied to treat cervical OA and are thought to have a pain-relief effect, but further studies are needed [8] (LoE: 1B).

With current evidence at our disposal we can suggests that electrical stimulation therapy may provide significant improvements for osteoarthritis , but in addition they recommend that further studies are undertaken [18].

• Acupuncture

The studies about acupuncture and osteoarthritis show small significant benefits which didn’t meet the pre-defined thresholds for clinical relevance. Most of the benefits are at least partially placebo effect. This has to be considered when choosing this option for the treatment [19].

• Ultrasound

Ultrasound may be beneficial but there’s a lot of low quality evidence about ultrasound and osteoarthritis. Most studies investigate whether it’s effective for hip and knee osteoarthritis. Ultrasound may be effective but it’s still unclear about the magnitude of the effects on pain relief and function. We have to consider that a part of the effect may still be due to placebo [20]. .

• Pain relief

TENS can also provide symptomatic relief. Pain may also be diminished using a medical treatment consisting of NSAIDs and [1] (LoE: 1A) [7] (LoE: 1A) [8] (LoE: 1B).

• Improving Physical activity and joint mobility

Another important part of the management of OA is exercise therapy. The exercise program should aim at mobilization exercises, strengthening local muscles around the affected joint and improving overall aerobic fitness [1] (LoE: 1A) [7] (LoE: 1A) [8] (LoE: 1B).

There is considerable evidence that states that physical activity can help in in the management of chronic pain that is the direct cause of osteoarthritis. Physical activity should play a key role in the therapy. This will improve the disability over time and also reduce pain. Improving the patient physical level will also have multiple other health benefits.

Patients with chronic pain will have difficulties with the therapy but small changes in the beginning can also have great effect on the outcome.

Therapy

• Encouragement and motivation [21]

o Management techniques

o Small changes

o Feedback

o Exercise contract

Finally, the treatment for cervical OA should also aim at providing information related to the disorder, stress management and postural advice in daily activities, work and hobbies [7].

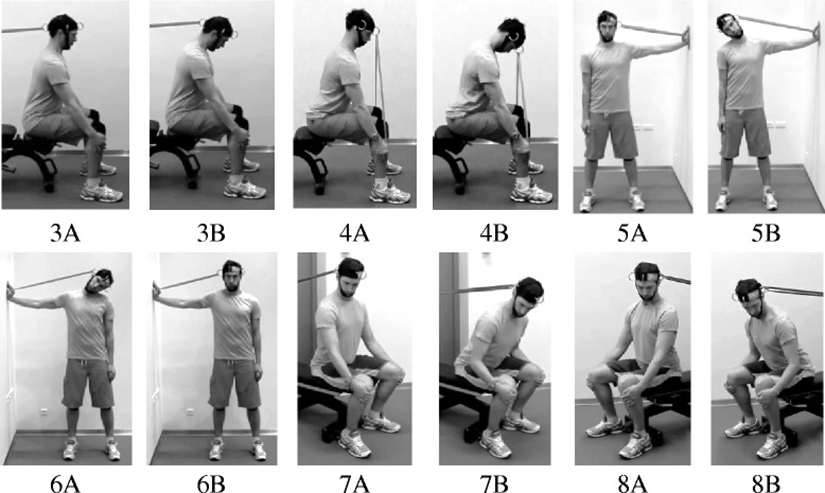

Thera-band: 6 color-coded levels of resistance (red, green, blue, black, silver and gold)

A training program consisted of four training exercises for the prime movers of the neck during cervical flexion, extension and lateral flexion. Exercises were performed with a head harness (Neck Flex) using different color-coded elastic resistance bands (Thera-Band®).

During the exercises it is advised to maintain a proper posture:

• Keep a straight back

• Position their head in an anatomically neutral position

• Lean the trunk forward (~20-30°)

• Arms were held straight with the hands placed underneath the knees

Cervical flexion against resistance (Fig. 3)

A Thera-Band is stretched between a door anchor and the back of the head harness. During the exercise, the participants have to perform a low cervical spine flexion (against resistance) followed by a low cervical spine extension.

Cervical extension against resistance (Fig. 4)

During neck extension, participants are positioned in the same way as during neck flexion, but the Thera-Band is stretched between the hands and front of the head harness. The exercise is performed with a low cervical spine flexion followed by a low cervical spine extension (against resistance)

Lateral flexion against resistance (Fig. 5, 6)

Lateral flexion is performed standing erect with the head in an anatomically neutral position. One hand has to be placed horizontally against a wall and a Thera-Band is stretched between the hand and side of the head harness. The exercise is performed with a low lateral spine flexion followed by a low lateral spine extension (against resistance). The exercise has to be performed for the right (Fig. 3, Exercise 5) and left side.

Flexion and rotation against rotation (Fig. 7, 8)

This exercise can be introduced afterwards as a complementary part of the therapy. The exercise is performed seated with a straight back and trunk leaned forward (~20°). The head is held in an anatomically neutral position and rotated approximately 45° degrees to either the right or left side. A Thera-Band has to be stretched between the head harness and a door anchor.

Keeping a static upper body, the hips has to be flexed and the body also (against resistance) this is followed by an extension. The exercise has to be performed to the right and left side [22].

Key Research[edit | edit source]

Alfred C. Gellhorn et al., Osteoarthritis of the spine: the facet joints, Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013 April; 9(4): 216–224 (LoE: 1A)

Resources[edit | edit source]

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

With osteoarthritis being a common disease among the general population more attention should be drawn to this disease. A lot of research is done concerning knee and hip OA but more research is needed for cervical OA. Though It may be clear that physiotherapists can have an influence on a patient with cervical OA especially in terms of daily life.

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

References [edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Walker JA, Osteoarthritis: pathogenesis, clinical features and management. Nursing Standard 2009, Vol. 24, Nr. 1, 35-40. (level A1) Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Walker" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 2.0 2.1 Boucher P, Postural control in people with osteoarthritis of the cervical spine. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, Volume 31, Number 3, p.184-190 (level B)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Alfred C. Gellhorn et al., Osteoarthritis of the spine: the facet joints, Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013 April ; 9(4): 216–224

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Wilder FV, Radiographic cervical spine osteoarthritis progression rates: a longitudinal assessment. Rheumatol Int (2011) 31:45–48 (level B)

- ↑ Michael J. Lee, K.Daniel Riew. The prevalence cervical facet arthrosis: an osseous study in cadaveric population. The spine Journal 9(2009) 711-714

- ↑ Hartz A J, Fisher M E, Bril G, et al. The association of obesity with joint pain and osteoarthritis in the HANES data. J Chronic Dis 1986;39:311-319

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Binder A, Cervical spondylosis and neck pain. BMJ. 2007 Mar 10;334(7592):527-531 (level A1)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Sutbeyaz ST, The effect of pulsed electromagnetic fields in the treatment of cervical osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled trial. Rheumatol Int (2006) 26: 320–324 (level A2)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Sinusas K., Osteoarthritis: diagnosis and treatment, Am Fam Physician, 2012 Jan 1;85(1):49-56.

- ↑ Robert W. Rand and Paul H. Crandall, Surgical treatment of cervical osteoarthritis, Calif Med. 1959 Oct; 91(4): 185–188.

- ↑ Grob D. et al., Transarticular screw fixation for osteoarthritis of the atlanto-axial segment, Eur spine journal 2006 Mar; 15(3):283:91 (Level of evidence: 3B)

- ↑ Arno Bisschop, Which factors prognosticate spinal instability following lumbar laminectomy?,Eur Spine J. 2012 Dec; 21(12): 2640–2648.

- ↑ Singh J.A. et al., Chondroitin for osteoarthritis, 2015, Cochrane review. (Level of evidence: 1A)

- ↑ Cibulka M.T. et al., Hip pain and mobility deficits - hip osteoarthritis: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association, J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 39 (2009), pp A1-25

- ↑ MQIC, Medical management of adults with osteoarthritis, Michigan Quality Improvement Consortium (2011)

- ↑ Peter W.F. et al., Physiotherapy in hip and knee osteoarthritis: development of practice guideline concerning initial assessment, treatment and evaluation, Acta Reumatol Port, 36 (2011), pp 268-281.

- ↑ Loew L. et al, Ottawa panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for aerobic walking programs in the management of osteoarthritis, Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 93 (2012), pp 1269-1285. (Level of evidence 2A)

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Hulme J. et al., Electromagnetic fields for the treatment of osteoarthritis., Hulme J1, Robinson V, Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(1):CD003523. (Level of evidence: 1A

- ↑ Manheimer E. et al., Acupuncture for osteoarthritis, 2010, Cochrane review. (Level of evidence: 1A)

- ↑ Rutjes A. W. S. et al., Therapeutic ultrasound for osteoarthritis, 2010, Cochrane review. (Level of evidence: 1A)

- ↑ Marley J; et al. A systematic review of interventions aimed at increasing physical activity in adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain, Syst Rev. 2014 Sep 19; 3:106) (Level of evidence: 1A)

- ↑ Mike Murray et al. Specific exercise training for reducing neck and shoulder pain among military helicopter pilots and crew members: a randomized controlled trial protocol, BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015; 16: 198. (Level of evidence: 1B)