Breathing Pattern Disorders

Original Editor - Leon Chaitow

Top Contributors - Rachael Lowe, Leon Chaitow, Admin, Jess Bell, Ewa Jaraczewska, Kim Jackson, Khloud Shreif, Tarina van der Stockt, Wanda van Niekerk, Fasuba Ayobami, Lucinda hampton, 127.0.0.1, Ajay Upadhyay, WikiSysop, Marleen Moll, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Evan Thomas, Scott Buxton and Venus Pagare /r

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Breathing Pattern Disorders (BPD) or Dysfunctional Breathing are abnormal respiratory patterns, specifically related to over-breathing. They range from simple upper chest breathing to, at the extreme end of the scale, hyperventilation (HVS).[1]

Dysfunctional breathing (DB) is defined as chronic or recurrent changes in the breathing pattern that cannot be attributed to a specific medical diagnosis, causing respiratory and non-respiratory complaints.[1] It is not a disease process, but rather alterations in breathing patterns that interfere with normal respiratory processes. BPD can, however, co-exist with diseases such as COPD or heart disease.[2][3]

BPDs are whole person problems - dysfunctional breathing can destabilise mind, muscles, mood and metabolism.[4] They can play a part in, for instance, premenstrual syndrome,[5] chronic fatigue,[6] neck, back and pelvic pain,[7][8] fibromyalgia[9] [10] and some aspects of anxiety and depression.[1][11]

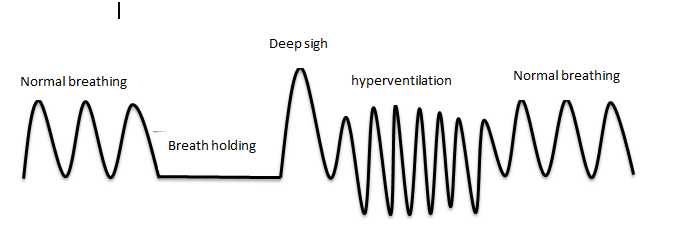

That figure describes normal and abnormal breathing pattern. Breath-holding: breath that held for a period of time. Deep sigh: is a deep inspiration. Hyperventilation: increase in RR/tidal volume.[12]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The human respiratory system is located in the thorax. The thoracic wall consists of skeletal and muscular components, extending between the 1st rib superiorly and the 12th rib, the costal margin and the xiphoid process inferiorly.[13] The respiratory system can be classified in terms of function and anatomy. Functionally, it is divided into two zones. The conducting zone extends from the nose to the bronchioles and serves as a pathway for conduction of inhaled gases. The respiratory zone is the second area and it is the site for gaseous exchange. It comprises of alveolar duct, alveolar sac and alveoli. Anatomically, it is divided into the upper and lower respiratory tract. The upper respiratory tract starts proximally from the nose and ends at the larynx while the lower respiratory tract continues from the trachea to the alveoli distally.[14]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Around 10% of patients in a population are diagnosed with hyperventilation syndrome.[16] However, many more people have subtle, yet clinically significant, breathing pattern disorders. Dysfunctional breathing is more prevalent in women (14%) than in men (2%).[16]

Little is known about dysfunctional breathing in children. Preliminary data suggest 5.3% or more of children with asthma have dysfunctional breathing and that, unlike in adults, it is associated with poorer asthma control. It is not known what proportion of the general pediatric population is affected.[17]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Breathing pattern disorders occur when ventilation exceeds metabolic demands, resulting in symptom-producing haemodynamic and chemical changes. Habitual failure to fully exhale - involving an upper chest breathing pattern - may lead to hypocapnia - ie a deficiency of carbon dioxide in the blood. The result is respiratory alkalosis, and eventually hypoxia, or the reduction of oxygen delivery to tissue.[18] [19]

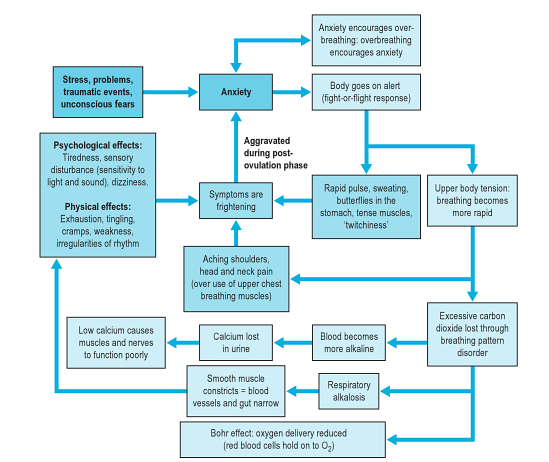

As well as having a marked effect on the biochemistry of the body, BPDs can influence emotions[20], circulation, digestive function as well as musculoskeletal structures involved in the respiratory process. Essentially a sympathetic state and a subtle, yet a fairly constant state of fight-or-flight becomes prevalent. This can cause anxiety, as well as changes in blood pH, muscle tone, pain threshold, and many central and peripheral nervous system symptoms. So despite not being a disease, BPDs are capable of producing symptoms that mimic pathological processes, including gastrointestinal or cardiac problems.[2][3]

Musculoskeletal imbalances often exist in patients with BPDs. These may result from a pre-existing contributing factor or may be caused by the dysfunctional breathing pattern.[21] Types of imbalances include loss or thoracic mobility, overuse/tension in accessory respiratory muscles and dysfunctional postures that affect the movement of the chest wall, as well as exacerbating poor diaphragmatic descent.[21]

This diagram below (from [22]) shows the stress-anxiety-breathing flow chart demonstrating multiple possible effects and influences of breathing pattern disorders.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Breathing pattern disorders manifest differently based on the individual. Some people may exhibit high levels of anxiety/fear whereas others have more musculoskeletal symptoms, chronic pain and fatigue.[21] Over 30 possible symptoms have been described in relation to BPDs/HVS.[21]

Typical symptoms can include:

- Frequent sighing and yawning

- Breathing discomfort

- Disturbed sleep

- Erratic heartbeats

- Feeling anxious and uptight

- Pins and needles

- Upset gut/nausea

- Clammy hands

- Chest Pains

- Shattered confidence

- Tired all the time

- Achy muscles and joints

- Dizzy spells or feeling spaced out

- Irritability or hypervigilance

- Feeling of 'air hunger'

- Breathing discomfort

- There may also be a correlation between BPD and low back pain.[23]

Classification[edit | edit source]

As DP mimic other serious conditions, that’s why it is difficult to detect the prevalence of PPD/DP and managements of PPD. Recent years, the researchers suggested an alternative classification for PPD/DP.[12]

| classification | definition |

|---|---|

| Barker and Everard[24] | |

| Thoracic DB | Upper chest wall activity with or without accessory muscles activation, sighing and irregular respiratory pattern |

| Extrathoracic DB | Upper airway impairment manifested in combination with breathing pattern disorders (e.g., vocal cord dysfunction) |

| Functional DB (a subdivision of thoracic and extrathoracic DB) | No structural or functional alterations directly associated with the symptoms of DB (e.g., phrenic nerve palsy, myopathy, and diaphragmatic eventration((one leaf of diaphragm elevated compared to another leaf)) ) |

| Structural DB (a subdivision of thoracic and extrathoracic DB) | Primarily associated with anatomical or neurological alterations (e.g., subglottic stenosis and unilateral cord palsy) |

| Boulding et al[25] | |

| Hyperventilation syndrome | Associated with respiratory alkalosis or independent of hypocapnia |

| Periodic deep sighing | associated with sighing , irregular breathing pattern and may overlap with hyperventilation |

| Thoracic dominant breathing | Associated with higher levels of dyspnoea , Can manifest more often in somatic diseases where there’s need to increase ventilation. |

| Forced abdominal expiration | when there is inappropriate and excessive abdominal muscle contraction to assist expiration. occurs as normal physiologic adaptation in COPD and pulmonary hyperinflation. |

| Thoracoabdominal asynchrony | ineffective respiratory mechanics that happen due to delay between rib cage and abdominal contraction occurs as normal physiological response in upper airway obstruction |

Co-existing Problems[edit | edit source]

Asthma and COPD[edit | edit source]

During an acute asthma attack, patients adopt a breathing pattern that is similar to the pattern seen in BPD:

- hyper-inflated

- rapid

- upper chest

- shallow[21]

It is therefore believed that patients with chronic asthma may be more likely to develop BPDs.[21] Thus, after an acute attack, it is important to re-establish abdominal/nose breathing patterns and normalised CO2 levels.[22] Similarly, exercise is commonly considered a trigger for asthma, but in some patients, their breathlessness may actually be due to hyperinflation and the increased respiratory effort from faulty breathing patterns.[21]

Chronic Rhinosinusitis (CRS)[edit | edit source]

Chronic mouth breathing often occurs with CRS and can, therefore, result in a chronic breathing pattern dysfunction. Saline nasal rises and eucalyptus steam inhalations can ease sinus congestion and restore nasal breathing. Because CRS is common in HVS/BPD patients, restoring nose breathing is a high priority in breathing retraining programmes.[22]

Chronic Pain[edit | edit source]

Chronic pain and chronic hyperventilation often co-exist. Pain can cause an increase in respiratory rates generally. Moreover, patients with abdominal or pelvic pain often splint their abdominal muscles, which results in upper chest breathing. When treating patients with chronic pain, it is important to work towards achieving nose/abdominal breathing, as well as promoting relaxation.[22]

Hormonal Influences[edit | edit source]

Progesterone is a respiratory stimulant. As it peaks in the post-ovulation phase, it may drive PaCO2 levels down. These levels further reduce in pregnancy.[22] It has been found that patients with PMS can benefit from breathing retraining and education to reduce any symptoms related to HVS.[22] Similarly, peri/postmenopausal women who cannot take HRT have been shown to benefit from breathing retraining to improve sleep and reduce hot flushes.[22]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Capnography[edit | edit source]

Capnography is a reliable diagnostic tool for BPDs. It measures the average CO2 partial pressure at the end of exhalation (End Tidal CO2).[26][27]

Nijmegen Questionnaire[edit | edit source]

High scores on the Nijmegen questionnaire have been shown to be both sensitive and specific for detecting people with tendencies consistent with breathing pattern disorders. The sensitivity of the Nijmegen Questionnaire in relation to the clinical diagnosis was 91% and the specificity 95%[28]

Assessment of Breathing Patterns[edit | edit source]

- Breath Holding – Ask the patient to exhale and then hold his/her breath. People are usually able to hold their breath for 25 to 30 seconds.[29] If a patient holds less than 15 seconds, it may indicate low tolerance to carbon dioxide.

- Breathing Hi-Low Test - Patient is either seated or supine – Place your hands on the patient’s chest and stomach. Ask the patient to exhale fully and then inhale normally. Observe where the movement initiates and where the most movement occurs. Look specifically for lateral expansion and upward hand pivot.[29]

- Breathing Wave – Patient lies prone. Ask him/her to breathe normally. The spine should move in a wave-like pattern towards the head. Segments that rise as a group may represent thoracic restrictions.[29]

- Seated Lateral Expansion – Place hands on lower thorax and monitor motion while breathing. Looking for symmetrical lateral expansion.[29]

- Manual Assessment of Respiratory Motion (MARM) - Assess and quantify breathing pattern, in particular, the distribution of breathing motion between the upper and lower parts of the rib cage and abdomen under various conditions. It is a manual technique that once acquired is practical, quick and inexpensive.[30]

- Sniff Test - Assesses bilateral diaphragm function. It is useful in assessing for upper or lower chest pattern dominance. The therapist places his/her hand 3 fingers below the patients xiphoid process. The patient performs a quick sniff. The therapist should feel an outward movement of the abdominal wall. This indicates that both hemi-diaphragms are working. Upper chest breathers usually have no diaphragmatic excursion or they may in-draw their abdominal wall.[29]

- Respiratory Induction Plethysmography (RIP) and Magnetometry: consists of two sinusoid wires coils insulated and placed one around thoracic (placed around the rib cage under the armpits) and the second(placed around the abdomen at the level of the umbilicus). The frequency from these wires coils converted to digital respiration wave form that is an indicator for inspired breath volume.

Assessment of the Musculoskeletal System[edit | edit source]

- Observe for elevated and depressed ribs and clavicle with rib palpation techniques.

- Check for muscle tone and length especially in the psoas, quadratus lumborum, latissimus dorsi, upper trapezius, scalene, and sternocleidomastoid.

- Assess for alterations in the mobility of the thoracic and rib articulations.

Assessment of Respiratory Function[edit | edit source]

- Oximetry - to measure oxygen saturation (SpO2)

- Capnography - to measure end-tidal CO2 levels in exhaled air (as described above)

- Peak expiratory flow rate - the highest flow of air out of the lungs from peak inspiration in a fast single forced breath out

- Manual Assessment of Respiratory Motion (MARM)

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Nijmegen Questionnaire

- Rowley Breathing Self-Efficacy Scale (RoBE)[32]

- Self Evaluation of Breathing Questionnaire )SEBQ)[33]

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Questionnaire (HAD)[34]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

BPDs can often mimic more serious conditions such as cardiac, neurological and gastrointestinal conditions. These must all be ruled out by the medical team.

Management[edit | edit source]

For information on the management of BPDs, click here.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Lum LC. Hyperventilation syndromes in medicine and psychiatry: a review. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1987 Apr;80(4):229-31..

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Sueda S et al. 2004 Clinical impact of selective spasm provocation tests Coron Artery Dis 15(8):491–497

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ajani AE, Yan BP. The mystery of coronary artery spasm. Heart, Lung and circulation. 2007 Feb 1;16(1):10-5.

- ↑ Peters, D. Foreword In: Recognizing and Treating Breathing Disorders. Chaitow, L., Bradley, D. and Gilbert, C. Elsevier, 2014

- ↑ Ott HW, Mattle V, Zimmermann US, Licht P, Moeller K, Wildt L. Symptoms of premenstrual syndrome may be caused by hyperventilation. Fertility and sterility. 2006 Oct 1;86(4):1001-e17.

- ↑ Nixon PG, Andrews J. A study of anaerobic threshold in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). Biological Psychology. 1996;3(43):264.

- ↑ Smith MD, Russell A, Hodges PW. Disorders of breathing and continence have a stronger association with back pain than obesity and physical activity. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 2006 Jan 1;52(1):11-6.

- ↑ Haugstad GK, Haugstad TS, Kirste UM, Leganger S, Wojniusz S, Klemmetsen I, Malt UF. Posture, movement patterns, and body awareness in women with chronic pelvic pain. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2006 Nov 1;61(5):637-44.

- ↑ Naschitz JE, Mussafia-Priselac R, Kovalev Y, Zaigraykin N, Elias N, Rosner I, Slobodin G. Patterns of hypocapnia on tilt in patients with fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, nonspecific dizziness, and neurally mediated syncope. The American journal of the medical sciences. 2006 Jun 1;331(6):295-303.

- ↑ Dunnett AJ, Roy D, Stewart A, McPartland JM. The diagnosis of fibromyalgia in women may be influenced by menstrual cycle phase. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2007 Apr 1;11(2):99-105.

- ↑ Han JN, Stegen K, De Valck C, Clement J, Van de Woestijne KP. Influence of breathing therapy on complaints, anxiety and breathing pattern in patients with hyperventilation syndrome and anxiety disorders. Journal of psychosomatic research. 1996 Nov 1;41(5):481-93.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Vidotto LS, Carvalho CR, Harvey A, Jones M. Dysfunctional breathing: what do we know?. Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia. 2019;45(1).

- ↑ Kennedy JW (2012). Clinical Anatomy Series‐Lower Respiratory Tract Anatomy. Scottish Universities Medical Journal.1 (2).p174‐179

- ↑ Patwa A, Shah A. Anatomy and physiology of respiratory system relevant to anaesthesia. Indian journal of anaesthesia. 2015 Sep;59(9):533.

- ↑ Osmosis. Anatomy and physiology of the respiratory system. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0fVoz4V75_E[last accessed 14/4/2020]

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Thomas M1, McKinley RK, Freeman E, Foy C, Price D.The prevalence of dysfunctional breathing in adults in the community with and without asthma. Prim Care Respir J. 2005 Apr;14(2):78-82.

- ↑ Barker NJ, Jones M, O'Connell NE, Everard ML. Breathing exercises for dysfunctional breathing/hyperventilation syndrome in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013(12).

- ↑ Palmer BF. Evaluation and treatment of respiratory alkalosis. American journal of kidney diseases. 2012 Nov 1;60(5):834-8.8.

- ↑ Jensen FB. Red blood cell pH, the Bohr effect, and other oxygenation‐linked phenomena in blood O2 and CO2 transport. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 2004 Nov;182(3):215-27.

- ↑ van Dixhoorn J 2007. Whole-Body breathing: a systems perspective on respiratory retraining. In: Lehrer P et al . (Eds.) Principles and practice of stress management. Guilford Press. NY pp. 291–332

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 CliftonSmith T, Rowley J. Breathing pattern disorders and physiotherapy: inspiration for our profession. Physical therapy reviews. 2011 Feb 1;16(1):75-86.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 22.6 Chaitow, L., Bradley, D. and Gilbert, C. Recognizing and Treating Breathing Disorders. Elsevier, 2014

- ↑ McLaughlin L, Goldsmith CH, Coleman K. Breathing evaluation and retraining as an adjunct to manual therapy Man Ther. 2011 Feb;16(1):51-2.

- ↑ Barker N, Everard ML. Getting to grips with ‘dysfunctional breathing’. Paediatric respiratory reviews. 2015 Jan 1;16(1):53-61.

- ↑ Boulding R, Stacey R, Niven R, Fowler SJ. Dysfunctional breathing: a review of the literature and proposal for classification. European Respiratory Review. 2016 Sep 1;25(141):287-94.

- ↑ Bradley H, Esformes J. Breathing pattern disorders and functional movement. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014 Feb;9(1):28-39.

- ↑ McLaughlin L. Breathing evaluation and retraining in manual therapy. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2009 Jul 1;13(3):276-82.

- ↑ van Dixhoorn J, Duivenvoorden HJ. Efficacy of Nijmegen Questionnaire in recognition of the hyperventilation syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29(2):199-206.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 Chaitow, L. Dysfunctional Breathing Course Videos. Physioplus 2019. https://members.physio-pedia.com/2014/04/01/breathing-disorders/#resource

- ↑ Rosalba Courtney, Jan van Dixhoorn, Marc Cohen; Evaluation of Breathing Pattern: Comparison of a Manual Assessment of Respiratory Motion(MARM) and Respiratory Induction Plethysmography. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback (2008) 33:91–100

- ↑ UFGATEP2014. DrWest seated lateral rib expansion. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=by45ML3QMXA[last accessed 16/4/2020]

- ↑ Jade Shaw. Current clinical practices, experiences, and perspectives of healthcare practitioners who attend to dysfunctional breathing: A qualitative studyhttp://unitec.researchbank.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10652/3589/MOst_Jade%20Shaw.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed 16th September, 2017)

- ↑ Rosalba Courtney, Kenneth Mark Greenwood, Marc Cohen. Relationships between measures of dysfunctional breathing in a population with concerns about their breathing. Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies (2011) 15, 24-34

- ↑ http://www.svri.org/documents/health-and-well-being (Accessed 16th September, 2017)