Autonomic Dysreflexia

Top Contributors -

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Autonomic dysreflexia is a life-threatening condition that arises after a Spinal Cord Injury, usually when the damage has occurred at or above the T6 level. It is generally defined as a syndrome in susceptible Spinal Cord injured patients that incorporates a sudden, exaggerated reflexive increase in blood pressure in response to a stimulus, usually bladder or bowel distension, originating below the level of the neurological injury. It is also sometimes known as autonomic hyperreflexia, hypertensive autonomic crisis, sympathetic hyperreflexia, autonomic Spasticity, paroxysmal hypertension, mass reflex, and viscero-autonomic stress syndrome[1]. Guillain–Barré Syndrome may also cause autonomic dysreflexia[2].

Dysregulation of the Autonomic Nervous System leads to an uncoordinated sympathetic response that may result in a potentially life-threatening hypertensive episode when there is a noxious stimulus below the level of the spinal cord injury. It is commonly presented by a severe headache, bradycardia, facial flushing, pallor, cold skin, and sweating in the lower half of the body [3].

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Steps:

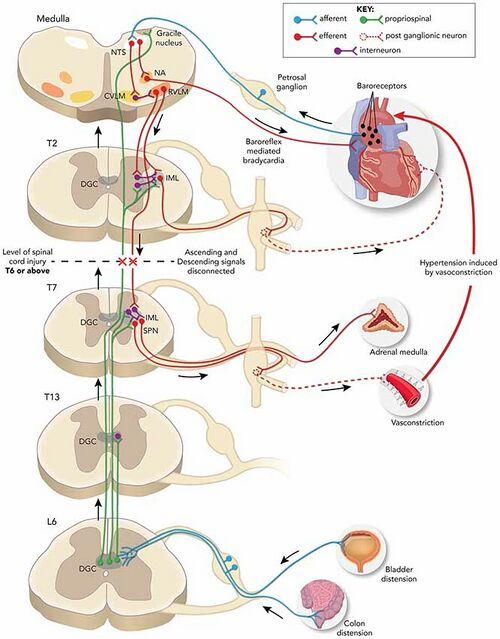

- Cutaneous or visceral stimulation below the level of the injury initiates afferent impulses to the intermediolateral grey columns of the spinal cord that elicit abnormal reflex sympathetic nervous system activity from T6 to L2.

- The sympathetic response is increased due to a lack of compensatory descending parasympathetic stimulation and intrinsic post-traumatic hypersensitivity. This causes diffuse vasoconstriction, typically to the lower 2/3 of the body, and a significant rise in blood pressure despite maximum parasympathetic vasodilatory efforts above the level of injury (In an intact autonomic system, this increased blood pressure activates the carotid sinus and aortic arch baroreceptors leading to a parasympathetic response slowing the heart rate via vagal nerve activity and causing diffuse vasodilation to correct the original increased sympathetic tone[4].

- In a person with spinal cord injury, the normal corrective parasympathetic response from the medullary vasomotor center cannot travel below the level of the spinal injury, and generalized vasoconstriction affects the splanchnic, muscular, vascular, and cutaneous arterial circulatory networks continues, ultimately leading to systemic hypertension which is often severe and potentially life-threatening.

- The compensatory vagal and parasympathetic stimulation leads to bradycardia and vasodilation, but only above the level of the spinal cord injury[5].

The most common cause is the distention of the bladder but could also be the rectum. Bladder distention is the most common cause for about 85% of all cases and is by far the most common trigger followed by fecal impaction. Pressure sores/ulcers or other injuries such as fractures and urinary tract infections are other common causes[6].

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The cause of this condition is a spinal cord injury, commonly at or above the T6 level. In the examination, AD episode is described an increase in systolic blood pressure of at least 25 mm Hg or more above baseline[5]. A severe episode would usually have a systolic blood pressure of at least 150 mmHg or more than 40mmHg above the patient's baseline. The higher the injury level, the greater the severity of the cardiovascular dysfunction. The severity and frequency of autonomic dysreflexia episodes are also associated with the severity of the spinal cord injury as well as the level. Patients with a complete spinal cord injury are more than three times more likely to develop autonomic dysreflexia than those with incomplete injuries (91% to 27%)[7].

Autonomic dysreflexia does not develop until after the period of spinal shock when reflexes have recovered[5]. The earliest reported case appeared on the fourth-day post-injury. Most of the patients (92%) who will ultimately develop autonomic dysreflexia will do so within the first year after their injury.

The six "B"s that are the common triggers of autonomic dysreflexia[1]:

- Bladder (catheter blockage, distension, stones, infection, spasms)

- Bowel (constipation, impaction)

- Back passage (hemorrhoids, rectal issues, anal abscess, fissure)

- Boils (skin lesions, infected ulcers)

- Bones (fractures, dislocations)

- Babies (pregnancy)

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Acute autonomic dysreflexia is characterised by

1. Severe Paroxysmal Hypertension associated with throbbing Headaches

2. Profuse sweating, nasal stuffiness, piloerection above the level of injury

3. Flushing of the skin above the level of the lesion, cool, pale skin below the level of injury because of severe vasoconstriction

4. Bradycardia

5. Visual disturbances, dizziness and anxiety or feeling of doom, which is sometimes accompanied by cognitive impairment[8][1][5].

Complications[edit | edit source]

Severe Hypertension may cause a hypertensive crisis complicated by pulmonary edema, left ventricular dysfunction, retinal detachment, intracranial hemorrhage, seizures, or death. If the patient has coronary artery disease, an episode of autonomic dysreflexia may cause a myocardial infarction[5].

Any patient with paraplegia or quadriplegia who complains of a severe headache or is found unconscious should immediately undergo screening for possible autonomic dysreflexia by checking their blood pressure and comparing it to their baseline level. Systolic blood pressure >150 mmHg or >40 mmHg above baseline should be considered highly suggestive of autonomic dysreflexia and appropriate measures should be taken[1].

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The initial presenting complaint is usually a severe headache, typically described as throbbing. Susceptible individuals, usually with spinal cord lesions at or above T6, who complain of a severe headache should immediately have their blood pressure checked. If elevated, a presumptive diagnosis of autonomic dysreflexia can be made.[5] Prompt recognition and correction of the disorder, usually just by irrigating or changing their urinary Foley catheter, can be immediately life-saving. Unfortunately, the vast majority of nurses, emergency room staff, and physiotherapists are unfamiliar with autonomic dysreflexia and are unable to identify or treat it quickly[9][10]. This is quite problematic as they are often the first healthcare professionals to witness such an event where early recognition and immediate, proper treatment can literally be the difference between life and death[5].

Fortunately, most episodes are relatively mild and can be managed at home by the patient and their usual caregivers without acute medical intervention. Severe, life-threatening episodes are rarely encountered by most medical personnel except those who work in specialized tertiary care centers. This means that many medical professionals, even emergency personnel, may rarely see this condition acutely in its most severe form and may therefore not be familiar with its early recognition or immediate treatment protocol[8].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Autonomic dysreflexia develops in 48% to 70% of patients with a spinal cord injury above the T6 level and is quite unlikely to develop if the injury is below T10[4]. It has also been infrequently reported in non-traumatic spinal cord injury cases, such as radiation myelopathy and cisplatin-induced polyneuropathy[11].[13]

Patients prone to this disorder will usually have a documented or personal history of prior episodes, but health professionals need to be alert to an initial presentation without any known prior history of autonomic dysreflexia[5].

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The evaluation includes obtaining a history of previous autonomic dysreflexia episodes with the triggering event if known, monitoring vital signs, and watching for any developing signs and symptoms. The baseline blood pressure should be known and documented for future reference. Many patients with spinal cord injuries will have hypotension. Orthostatic hypotension is found in over 50% of patients with autonomic dysreflexia[12].

Start by identifying patients at risk (spinal cord injury at or above the T6 level) and recognize the key initial symptom, which is usually a severe headache from cerebral vasodilation. Should this be encountered, the next step would be to check the blood pressure. If elevated above the patient's usual baseline, then the patient is at high risk for an episode of autonomic dysreflexia. A systolic blood pressure >150 mmHg or >40 mmHg above baseline levels should be considered indicative of autonomic dysreflexia.

The likelihood of autonomic dysreflexia is independently predicted by the level of the spinal cord lesion, whether it is complete or incomplete, and the presence of neurogenic detrusor overactivity[1].

Management/Treatment[edit | edit source]

Ask the Patient and Caregiver: Since most patients will have endured previous episodes, it is reasonable to ask them what their most common precipitating event is and the usual remedy. Most patients with a history of autonomic dysreflexia will be quite knowledgeable about the condition and are prepared to implement a treatment plan. It is strongly recommended that patients prone to this condition carry an emergency treatment pack or kit with appropriate pharmacological therapies and a card or summary of autonomic dysreflexia to explain the condition and its acute treatment to those unfamiliar with it in emergency situations[1][5].

Immediate First Steps: In the event of an episode, the immediate first step is to sit the patient upright with their legs dangling and remove any tight clothing or constrictive devices, which will help lower their blood pressure orthostatically by inducing the pooling of blood in the abdominal and lower extremity vessels as well as eliminating possible triggering stimuli.[20] Vital signs should be closely monitored, and identification of the triggering stimulus should be immediately attempted. Blood pressure should be checked at least every 5 minutes, and an arterial line should be considered. The noxious stimuli should be corrected as soon as possible[13][1].

Bladder and/or bowel distension are the most common triggering causes, with bladder over-distension being the most likely. Therefore, checking and restoring bladder drainage is immediately recommended as the first source to be investigated. If the patient has an indwelling catheter, it should be evaluated for obstruction, malfunction, or malpositioning, and a workup for a urinary tract infection should be performed.

If the triggering event cannot be identified and initial maneuvers do not improve the systolic blood pressure below 150 mmHg or less than 40 mmHg above the patient's usual baseline, emergency antihypertensive pharmacologic management should be initiated. Hypertension should be promptly corrected with agents that optimally have a rapid onset but short duration of action[1].

Hospital Admission: Hospital admission is recommended if the patient is responding poorly to treatment, the underlying etiology of the episode remains unknown or in pregnancy. Transfer to an intensive care unit should be considered if control of the autonomic dysreflexia and its associated hypertensive crisis has not been achieved within 30 minutes[1].

Procedures: Patients with spinal cord injuries and autonomic dysreflexia often undergo medical procedures and surgeries, such as urologic instrumentation, that can trigger dysreflexic episodes. General or regional anesthesia may be used for these procedures when feasible. Regional anesthesia in the form of a spinal anesthetic has the advantage of blocking both limbs of the reflex arc and thereby avoids autonomic dysreflexia[1].

Prophylaxis: Optimal management of patients with spinal cord injuries who are prone to autonomic dysreflexia is usually achieved by a multidisciplinary team which may include a spinal rehabilitation specialist, urologist, gastroenterologist, and other specialists who are experienced in these cases. For example, patients may be asked to perform intermittent self-catheterization more often (5-6 times a day) than similar patients with neurogenic bladders who are not as susceptible to autonomic dysreflexia. Bowel management may include abdominal massage, periodic careful digital rectal stimulation, regular suppositories, and routine laxatives. Additional prophylactic measures include careful positioning, seating guidelines, use of appropriate pads along with pressure-relieving cushions and mattresses, as well as periodic inspections for skin lesions to minimize ulcers and breakdowns[1].

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

The prognosis of autonomic dysreflexia is usually good as long as the condition is recognized, patients and caregivers are adequately educated, proper precautions are taken, and emergency corrective treatment is initiated promptly. However, unrecognized or untreated autonomic dysreflexia can result in potentially catastrophic consequences. Fortunately, mortality is relatively rare[1].

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Acute glomerulonephritis

- Anxiety

- Cushing's syndrome

- Drug use or overdose (e.g., stimulants, especially alcohol, cocaine, or levothyroxine)

- Hyperaldosteronism

- Hyperthyroidism

- Intracranial hemorrhage

- Ischemic stroke

- Nephritic and nephrotic syndrome

- Polycystic kidney disease

Resources[edit | edit source]

An excellent free informational website devoted to patient and professional education about spinal cord injuries can be found at the International Spinal Cord Society (ISCoS) website. It provides educational modules designed for all stages and levels of spinal cord injury for both laypersons and healthcare personnel[5].

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Allen KJ, Leslie SW. Autonomic dysreflexia. InStatPearls [Internet] 2022 Feb 14. StatPearls publishing.

- ↑ Autonomic Dysreflexia https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001431.htm

- ↑ Cowan H, Lakra C, Desai M. Autonomic dysreflexia in spinal cord injury. bmj. 2020 Oct 2;371.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Karlsson AK. Autonomic dysreflexia. Spinal cord. 1999 Jun;37(6):383-91.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 Lakra C, Swayne O, Christofi G, Desai M. Autonomic dysreflexia in spinal cord injury. Practical neurology. 2021 Dec 1;21(6):532-8.

- ↑ Shergill IS, Arya M, Hamid R, Khastgir J, Patel HR, Shah PJ. The importance of autonomic dysreflexia to the urologist. BJU international. 2004 May;93(7):923-6.

- ↑ Del Fabro AS, Mejia M, Nemunaitis G. An investigation of the relationship between autonomic dysreflexia and intrathecal baclofen in patients with spinal cord injury. The journal of spinal cord medicine. 2018 Jan 2;41(1):102-5. BibTeXEndNoteRefManRefWorks

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Khastgir J, Drake MJ, Abrams P. Recognition and effective management of autonomic dysreflexia in spinal cord injuries. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2007 May 1;8(7):945-56.

- ↑ Kaydok E. Nurses and physiotherapists’ knowledge levels on autonomic dysreflexia in a rehabilitation hospital. The journal of spinal cord medicine. 2021 Dec 3:1-5.

- ↑ Tederko P, Ugniewski K, Bobecka-Wesołowska K, Tarnacka B. What do physiotherapists and physiotherapy students know about autonomic dysreflexia?. The journal of spinal cord medicine. 2021 May 4;44(3):418-24.

- ↑ Saito H. Autonomic dysreflexia in a case of radiation myelopathy and cisplatin-induced polyneuropathy. Spinal cord series and cases. 2020 Aug 13;6(1):1-5.

- ↑ Gibbons CH, Freeman R. Delayed orthostatic hypotension: a frequent cause of orthostatic intolerance. Neurology. 2006 Jul 11;67(1):28-32.

- ↑ Trop CS, Bennett CJ. Autonomic dysreflexia and its urological implications: a review. The Journal of urology. 1991 Dec 1;146(6):1461-9.