Autonomic Dysreflexia: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

== Management/Treatment == | == Management/Treatment == | ||

In the event of an episode, the physiotherapist should perform following steps: | In the event of an episode, the physiotherapist should perform the following steps: | ||

# Sit the patient upright with their legs dangling (lying the patient down is contraindicated). | # Sit the patient upright with their legs dangling (lying the patient down is contraindicated). | ||

| Line 90: | Line 90: | ||

# Check catheter for kink, block, fullness (notify nurse to empty if needed) | # Check catheter for kink, block, fullness (notify nurse to empty if needed) | ||

# Remove any tight clothing or constrictive devices, which will help lower their blood pressure by inducing the pooling of blood in the abdominal and lower extremity vessels as well as eliminating possible triggering stimuli. | # Remove any tight clothing or constrictive devices, which will help lower their blood pressure by inducing the pooling of blood in the abdominal and lower extremity vessels as well as eliminating possible triggering stimuli. | ||

# Look for another | # Look for another potentially noxious stimulus below NLI. | ||

# Vital signs should be closely monitored, and identification of the triggering stimulus should be immediately attempted. | # Vital signs should be closely monitored, and identification of the triggering stimulus should be immediately attempted. | ||

# Blood pressure should be checked at least every 5 minutes, and an arterial line should be considered. The noxious stimuli should be corrected as soon as possible<ref>Trop CS, Bennett CJ. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1942319/ Autonomic dysreflexia and its urological implications: a review. The Journal of urology.] 1991 Dec 1;146(6):1461-9.</ref><ref name=":0" />. | # Blood pressure should be checked at least every 5 minutes, and an arterial line should be considered. The noxious stimuli should be corrected as soon as possible<ref>Trop CS, Bennett CJ. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1942319/ Autonomic dysreflexia and its urological implications: a review. The Journal of urology.] 1991 Dec 1;146(6):1461-9.</ref><ref name=":0" />. | ||

Revision as of 23:03, 24 April 2022

Top Contributors -

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Autonomic dysreflexia (AD) is a life-threatening condition which is common after a Spinal Cord Injury occurred at or above the T6 level (Neurological level of injury) when there is a noxious stimulus below the level of the spinal cord injury. AD is characterized by a sudden, exaggerated reflexive increase in blood pressure in response to a noxious stimulus, commonly bladder or bowel distension, arising below the level of the neurological injury. [1].

Signs & Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Acute autonomic dysreflexia is characterized by

1. Severe Paroxysmal Hypertension associated with throbbing Headaches

2. Profuse sweating, nasal stuffiness, piloerection above the level of injury

3. Flushing of the skin above the level of the lesion (Vasodilatation)

4. Cool, pale skin below the level of injury (Vasoconstriction)

4. Bradycardia

5. Visual disturbances, dizziness and anxiety or feeling of doom, which is sometimes accompanied by cognitive impairment[2][1][3].

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

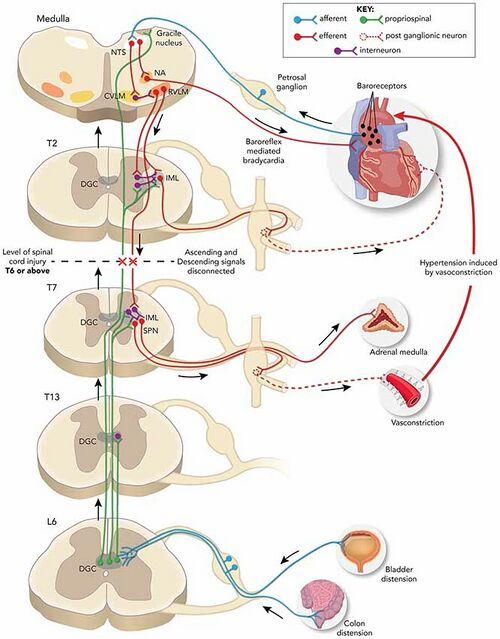

Cutaneous or visceral triggers below the level of the injury send afferent signals to the intermediolateral grey columns of the spinal cord that start abnormal reflex sympathetic nervous system activity from T6 to L2.

↓

The sympathetic response is increased due to a lack of compensatory descending parasympathetic stimulation and intrinsic post-traumatic hypersensitivity.

↓

Lead to diffuse vasoconstriction, typically to the lower 2/3 of the body, and a severe rise in BP despite maximum parasympathetic vasodilatory efforts above the level of injury (In an intact autonomic system, this increased blood pressure activates the carotid sinus and aortic arch baroreceptors leading to a parasympathetic response slowing the heart rate via vagal nerve activity and causing diffuse vasodilation to correct the original increased sympathetic tone[4].

↓

In a person with spinal cord injury, the normal parasympathetic response from the medullary vasomotor center cannot travel below the level of the spinal injury, and generalized vasoconstriction affects the splanchnic, muscular, vascular, and cutaneous arterial circulatory networks continues.

↓

This leads to systemic hypertension which is often severe and potentially life-threatening.

↓

The compensatory vagal and parasympathetic stimulation leads to bradycardia and vasodilation, but only above the level of the spinal cord injury[3].

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The cause of this condition is a spinal cord injury, commonly at or above the T6 level. In the examination, an AD episode has described an increase in systolic blood pressure of at least 20-25 mm Hg or more above baseline[3]. A severe episode would usually have a systolic blood pressure of at least 150 mmHg or more than 40mmHg above the patient's baseline. The higher the injury level, the greater the severity of the cardiovascular dysfunction. The severity and frequency of autonomic dysreflexia episodes are also associated with the severity of the spinal cord injury as well as the level. Patients with a complete spinal cord injury are more than three times more likely to develop autonomic dysreflexia than those with incomplete injuries (91% to 27%)[5].

Autonomic dysreflexia does not develop until after the period of spinal shock when reflexes have recovered[3]. The earliest reported case appeared on the fourth-day post-injury. Most of the patients (92%) who will ultimately develop autonomic dysreflexia will do so within the first year after their injury.

The six "B"s that are the common triggers of autonomic dysreflexia[1]:

- Bladder (catheter blockage, distension, stones, infection, spasms)

- Bowel (constipation, impaction)

- Back passage (hemorrhoids, rectal issues, anal abscess, fissure)

- Boils (skin lesions, infected ulcers)

- Bones (fractures, dislocations)

- Babies (pregnancy)

The most common cause is the distention of the bladder but could also be the rectum. Bladder distention is the most common cause for about 85% of all cases and is by far the most common trigger followed by fecal impaction. Pressure sores/ulcers or other injuries such as fractures and urinary tract infections are other common causes[6].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The initial presenting complaint is commonly a severe throbbing headache. If the patient with spinal cord injury at or above T6 complains of a severe headache should immediately have their blood pressure checked. If elevated, a presumptive diagnosis of autonomic dysreflexia can be made. The vast majority of first contact practitioners like nurses, emergency room staff, and physiotherapists are not very familiar with autonomic dysreflexia and are unable to identify or manage it promptly[7][8]. If the first contact healthcare professionals can identify and manage this condition, it can really make the difference between life and death[3].

Fortunately, most episodes are relatively mild and can be managed at home by the patient and their usual caregivers without acute medical intervention. Severe, life-threatening episodes are rarely encountered by most medical personnel except those who work in specialized tertiary care centers[2].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Autonomic dysreflexia affects 48% to 70% of patients with a spinal cord injury above the T6 level and is not very common to affect if the injury is below T10 in patients with spinal cord injury[4]. Guillain–Barré Syndrome may also cause autonomic dysreflexia[9].

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis can be made by obtaining a history of previous autonomic dysreflexia episodes with the triggering event if known, monitoring vital signs, and watching for any developing signs and symptoms. The baseline blood pressure should be known and documented for future reference. Many patients with spinal cord injuries will have hypotension. Orthostatic hypotension is found in over 50% of patients with autonomic dysreflexia[10].

Start by identifying patients at risk (spinal cord injury at or above the T6 level) and recognize the key initial symptom, which is usually a severe headache from cerebral vasodilation. Should this be encountered, the next step would be to check the blood pressure. If elevated above the patient's usual baseline, then the patient is at high risk for an episode of autonomic dysreflexia. A systolic blood pressure >150 mmHg or >40 mmHg above baseline levels should be considered indicative of autonomic dysreflexia[1].

Management/Treatment[edit | edit source]

In the event of an episode, the physiotherapist should perform the following steps:

- Sit the patient upright with their legs dangling (lying the patient down is contraindicated).

- Notify nearby nurse or doctor for assistance.

- Check catheter for kink, block, fullness (notify nurse to empty if needed)

- Remove any tight clothing or constrictive devices, which will help lower their blood pressure by inducing the pooling of blood in the abdominal and lower extremity vessels as well as eliminating possible triggering stimuli.

- Look for another potentially noxious stimulus below NLI.

- Vital signs should be closely monitored, and identification of the triggering stimulus should be immediately attempted.

- Blood pressure should be checked at least every 5 minutes, and an arterial line should be considered. The noxious stimuli should be corrected as soon as possible[11][1].

- Document.

If the triggering event cannot be identified and initial maneuvers do not improve the systolic blood pressure below 150 mmHg or less than 40 mmHg above the patient's usual baseline, the patient should receive immediate medical intervention.

Any patient with paraplegia or quadriplegia who complains of a severe headache or is found unconscious should immediately undergo screening for possible autonomic dysreflexia by checking their blood pressure and comparing it to their baseline level. Systolic blood pressure >150 mmHg or >40 mmHg above baseline should be considered highly suggestive of autonomic dysreflexia and appropriate measures should be taken[1].

Complications[edit | edit source]

Common complications of Autonomic Dysreflexia are:

- Pulmonary Edema

- Left Ventricular Dysfunction

- Retinal Detachment

- Intracranial Hemorrhage

- Seizures, or Death.

If the patient has coronary artery disease, an episode of autonomic dysreflexia may cause a Myocardial Infarction[3].

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

The prognosis of autonomic dysreflexia is good if the condition is identified early, and sufficient education is provided to the patient with spinal cord injury and caregivers.

However, unidentified or mismanaged autonomic dysreflexia can result in life-threatening consequences. Fortunately, mortality is relatively rare[1].

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Acute glomerulonephritis

- Anxiety

- Cushing's syndrome

- Drug use or overdose (e.g., stimulants, especially alcohol, cocaine, or levothyroxine)

- Hyperaldosteronism

- Intracranial hemorrhage

- Ischemic stroke

- Nephritic and nephrotic syndrome

- Polycystic kidney disease

Resources[edit | edit source]

An excellent free informational website devoted to patient and professional education about spinal cord injuries can be found at the International Spinal Cord Society (ISCoS) website. It provides educational modules designed for all stages and levels of spinal cord injury for both laypersons and healthcare personnel[3].

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Allen KJ, Leslie SW. Autonomic dysreflexia. InStatPearls [Internet] 2022 Feb 14. StatPearls Publishing.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Khastgir J, Drake MJ, Abrams P. Recognition and effective management of autonomic dysreflexia in spinal cord injuries. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2007 May 1;8(7):945-56.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Lakra C, Swayne O, Christofi G, Desai M. Autonomic dysreflexia in spinal cord injury. Practical neurology. 2021 Dec 1;21(6):532-8.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Karlsson AK. Autonomic dysreflexia. Spinal cord. 1999 Jun;37(6):383-91.

- ↑ Del Fabro AS, Mejia M, Nemunaitis G. An investigation of the relationship between autonomic dysreflexia and intrathecal baclofen in patients with spinal cord injury. The journal of spinal cord medicine. 2018 Jan 2;41(1):102-5. BibTeXEndNoteRefManRefWorks

- ↑ Shergill IS, Arya M, Hamid R, Khastgir J, Patel HR, Shah PJ. The importance of autonomic dysreflexia to the urologist. BJU international. 2004 May;93(7):923-6.

- ↑ Kaydok E. Nurses and physiotherapists’ knowledge levels on autonomic dysreflexia in a rehabilitation hospital. The journal of spinal cord medicine. 2021 Dec 3:1-5.

- ↑ Tederko P, Ugniewski K, Bobecka-Wesołowska K, Tarnacka B. What do physiotherapists and physiotherapy students know about autonomic dysreflexia?. The journal of spinal cord medicine. 2021 May 4;44(3):418-24.

- ↑ Autonomic Dysreflexia https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001431.htm

- ↑ Gibbons CH, Freeman R. Delayed orthostatic hypotension: a frequent cause of orthostatic intolerance. Neurology. 2006 Jul 11;67(1):28-32.

- ↑ Trop CS, Bennett CJ. Autonomic dysreflexia and its urological implications: a review. The Journal of urology. 1991 Dec 1;146(6):1461-9.