Lifestyle Medicine, Exercise and Nutrition for Managing Chronic Low Back Pain

Top Contributors - Stacy Schiurring, Kim Jackson, Jess Bell, Ewa Jaraczewska and Lucinda hampton

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The management of chronic low back pain (LBP) often requires a lifestyle change for long-lasting effect. Research shows that altering diet and increasing activity level through exercise can help improve subjective complaints of chronic LBP.[1][2] The biopsychosocial model considers the importance of behavioural modifications in the management of chronic LBP, introducing the concept of positive[3] or whole-person health[4] as a prevention strategy against long-term disability from chronic LBP.

“Whole person health refers to helping individuals improve and restore their health in multiple interconnected domains—biological, behavioral, social, environmental—rather than just treating disease. Research on whole person health includes expanding the understanding of the connections between these various aspects of health, including connections between organs and body systems.”[4]

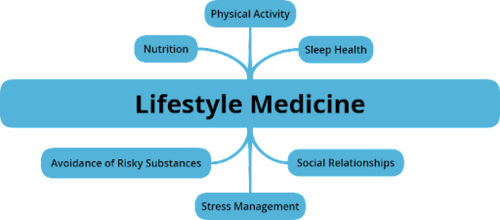

Lifestyle Medicine combines the modern western practice of medicine with evidence-based lifestyle therapeutic approaches to prevent and reverse lifestyle-related chronic illness. Examples of lifestyle practices include:

- Nutritional: Whole-food and plant-based diet, dietary supplements, probiotics

- Physical: Regular physical activity, acupuncture, massage, adequate sleep

- Psychological: meditation, hypnosis, music therapy, relaxation techniques

- Combination of the above: yoga, tai chi, dance therapy, art therapy.

This article will discuss the use of exercise and nutrition to manage chronic LBP within the framework of Lifestyle Medicine. This approach takes a holistic look at medicine and pain management and attempts to identify the root cause of pain rather than just treat its symptoms. It is recommended to consult a healthcare provider before starting a new exercise routine. Physiotherapists can create a unique individualised exercise routine appropriate for each client’s needs. In addition a dietician-nutritionist can assist to create individualised diet plans.

Conventional Exercises[edit | edit source]

Conventional exercises are common treatment prescriptions for physiotherapists. The use of these relatively inexpensive exercises as part of physiotherapy treatment have been found to reduce subjective LBP, disability, and overall quality of life.

- Aerobic training provides cardiovascular conditioning. Examples include: outdoor or treadmill walking, stationary cycling, stairclimber, elliptical walking, swimming, hiking, or sport activities.

- A 2005 study by Hoffman found people with chronic LBP and minimal to moderate levels of disability experienced exercise-induced analgesia for greater than 30 minutes following aerobic exercise.[5]

- A 2019 study by Vanti suggests a walking program alone can provide similar pain relief and improvements to disability, movement avoidance, and quality of life with a walking program combined with exercise, and an exercise program alone.[6]

- Resistance Training is any exercise that causes the muscles to contract against an external resistance with the expectation of increases in strength, power, hypertrophy, and/or endurance.

- A 2021 study by Tataryn found that resistive exercises targeting the extensor muscles of the thoracic and lumbar spine and hip can have a positive effect on preserved pain and level of disability.[7]

- A 2016 study by Michaelson found no significant difference in the effectiveness of high load lifting and low load motor control intervention on improving LBP and disability.[8]

- Flexibility Training is any exercise that increases the motion in a joint or group of joints, or the ability to move joints effectively through a complete range of motion.

Due to the complexities of LBP etiology, it is important to fully assess and evaluate a client prior to creating a physiotherapy plan of care. Often it is a combination of the above conventional exercises which will give an individual client their best results. It is also important to take a client’s needs and beliefs into consideration when creating a plan of care.[9][10]

Integrative Exercises[edit | edit source]

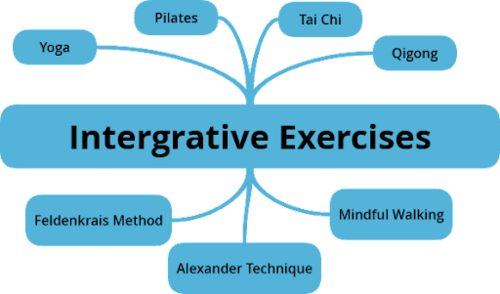

An alternative to conventional exercises is integrative exercises. This type of exercise is unique because they combine both physical and mental exercises and are part of a greater lifestyle change goal for sustainable wellness and health condition management. Integrative exercises indirectly address pain by improving physical conditioning, teaching pain-coping mechanisms, and addressing kinesiophobia by improving body awareness. In general, access to these are easily accessible, require little to no equipment, and are adaptable to a client’s needs and ability level.[11]

Examples of integrative exercises include:

- Yoga: began as a spiritual practice but has branched into a way of promoting physical and mental well-being. Yoga as practiced in the western countries typically emphasizes physical postures, breathing techniques, and meditation.[12] A 2020 meta-analysis found that yoga may decrease chronic LBP for the short to intermediate term and improve disability status from short to long term. This study also found that yoga had the same effect on pain and disability as conventional exercises and physiotherapy. [13]

- Pilates: A 2016 systematic review of nine random clinical trials found pilates provided short term pain reduction for persons with chronic LBP.[14]

- Tai Chi: Is a a series of slow mindfully produced movements pattern with stretching and deep breathing. Movements are continuous and flows from one posture to another.[15] A 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found that Tai Chi alone or when used with conventional exercises and physiotherapy may decrease pain and improve disability for persons with LBP. [16]

- Qigong: can be described as a mind-body-spirit practice that improves mental and physical health by integrating posture, mindful movements, breathing technique, self-massage, and sound.[17] A 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis of nine randomized controlled trials found that Baduanjin, a type of Qigong, is effective for LBP. [18]

- Mindful walking[19]

- Feldenkrais Method: A type of movement exercise which attempts to stimulate neuroplasticity by improving awareness of body awareness, flexibility, balance, and coordination.[20] A 2020 study found that the Feldenkrais method improved quality of life and decreased measured disability as compared to core stability exercises for non-specific chronic LBP.[21]

- Alexander Technique: A type of movement exercise which attempts to improve movement pattern efficiency, ease and comfort of range of motion, balance, and coordination through mindfulness of movement.[22] A 2008 study found that private Alexander Technique lessons from registered teachers have long term benefits on chronic LBP. The effectiveness of the lessons were increased when combined with conventional exercises.[23]

Many of these exercises involve moving through various postures, with the spine moving between flexion, extension, rotation, and sidebending, with postural strengthening. Read more about the benefits of movement and avoiding prolonged static postures on LBP here. Many of these exercises, most significantly yoga, tai chi, and qigong involve mediation and can address psychological and emotional needs for the person with chronic LBP.[12] More research is needed to strengthen the evidence for the use of these exercises in the treatment of chronic LBP.

Nutrition[edit | edit source]

It is strongly recommended to work with a nutritionist-dietician for optimal results and to strengthen interprofessional referrals and collaborations.

“Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food.” -Hippocrates

Purpose of Food

- Energy and survival

- Health and healing

- Maintain a healthy immune system

- Social interaction

Enhance our healthful eating experiences

- Choose a variety of colourful and predominantly plant-based foods

- Learn how to cook

- Mindful eating

Food as Medicine: Pain Relief

Sources: Martínez-Rodríguez A, Leyva-Vela B, Martínez-García A, Nadal-Nicolás Y. [Effects of lacto-vegetarian diet and stabilization core exercises on body composition and pain in women with fibromyalgia: randomized controlled trial]. Nutr Hosp. 2018;35(2):392-399. [article in Spanish]

Zick SM, Murphy SL, Colacino J. Association of chronic spinal pain with diet quality. Pain Rep. 2020;5(5):e837.

Elma Ö, Yilmaz ST, Deliens T, et al. Do nutritional factors interact with chronic musculoskeletal pain? a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2020;9(3):702.

Hashem LE, Roffey DM, Alfasi AM, et al. Exploration of the Inter-Relationships Between Obesity, Physical Inactivity, Inflammation, and Low Back Pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2018;43(17):1218-1224.

Perzia B, Ying G-S, Dunaief JL, Dunaief DM. (2020). Once-daily low inflammatory foods everyday (LIFE) smoothie or the full LIFE diet lowers C-Reactive protein and raises plasma beta-carotene in 7 days. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. October 2020. Electronic publication ahead of print.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- American College of Sports Medicine, https://www.acsm.org/

- American College of Lifestyle Medicine, https://www.lifestylemedicine.org/

- American Physical Therapy Association, https://www.apta.org/

- Chartered Society of Physiotherapy, https://www.csp.org.uk/

- National Strength and Conditioning Association, https://www.nsca.com/

- World Physiotherapy, https://world.physio/

- The Lancet – Physical Activity 2021, https://www.thelancet.com/series/physical-activity-2021

- American Society for Alexander Technique, www.amsatonline.org

- American Tai Chi and Qigong Association, www.americantaichi.org

- International Association of Yoga Therapists, www.iayt.org

- International Feldenkrais Federation, https://feldenkrais-method.org

- International Medical Tai Chi and Qigong Association, http://www.imtqa.org/

- National Qigong Association, http://nqa.org

- Pilates Method Alliance, www.pilatesmethodalliance.org

- Yoga Alliance, www.yogaalliance.org Berner P, Bezner JR, Morris D, Lein DH. Nutrition in physical therapist practice: setting the stage for taking action. Phys Ther. 2021;101(5):pzab062. doi:10.1093/ptj/pzab062 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33580960/ Berner P, Bezner JR, Morris D, Lein DH. Nutrition in physical therapist practice: tools and strategies to act now. Phys Ther. 2021;101(5):pzab061. doi:10.1093/ptj/pzab061 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33577673/ Physical Activity Measures Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire for Everyone (PAR-Q+) American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2022. http://eparmedx.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/January2020PARQPlusFillable.pdf Physiopedia – https://www.physio-pedia.com/Physical_Activity_and_Outcome_Measures Silfee VJ, Haughton CF, Jake-Schoffman DE, et al. Objective measurement of physical activity outcomes in lifestyle interventions among adults: A systematic review. Prev Med Rep. 2018;11:74-80. Strath SJ, Kaminsky LA, Ainsworth BE, et al. Guide to the assessment of physical activity: Clinical and research applications: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128(20):2259-2279. Sylvia LG, Bernstein EE, Hubbard JL, Keating L, Anderson EJ. Practical guide to measuring physical activity. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(2):199-208. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2013.09.018

- American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, www.eatright.org

- Forks Over Knives, www.forksoverknives.com

- Healthy Kitchens, Healthy Lives, www.healthykitchens.org

- Office of Dietary Supplements, https://ods.od.nih.gov/

- Sports, Cardiovascular, and Wellness Nutrition, www.scandpg.org

- Teaching Kitchen Collaborative, www.tkcollaborative.org PP page “Culinary Medicine for Health and Disease Management”

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Kirsch Micheletti J, Bláfoss R, Sundstrup E, Bay H, Pastre CM, Andersen LL. Association between lifestyle and musculoskeletal pain: cross-sectional study among 10,000 adults from the general working population. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2019 Dec;20(1):1-8.

- ↑ Wasser JG, Vasilopoulos T, Zdziarski LA, Vincent HK. Exercise benefits for chronic low back pain in overweight and obese individuals. PM&R. 2017 Feb 1;9(2):181-92.

- ↑ Buchbinder R, van Tulder M, Öberg B, Costa LM, Woolf A, Schoene M, Croft P, Hartvigsen J, Cherkin D, Foster NE, Maher CG. Low back pain: a call for action. The Lancet. 2018 Jun 9;391(10137):2384-8.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 National Institute of Health. Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s In a Name? Available from: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name (accessed 01/01/2022).

- ↑ Hoffman MD, Shepanski MA, Mackenzie SP, Clifford PS. Experimentally induced pain perception is acutely reduced by aerobic exercise in people with chronic low back pain. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005;42(2):183-190

- ↑ Vanti C, Andreatta S, Borghi S, Guccione AA, Pillastrini P, Bertozzi L. The effectiveness of walking versus exercise on pain and function in chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(6):622-632.

- ↑ Tataryn N, Simas V, Catterall T, Furness J, Keogh JWL. Posterior-chain resistance training compared to general exercise and walking programmes for the treatment of chronic low back pain in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med Open. 2021;7(1):17.

- ↑ Michaelson P, Holmberg D, Aasa B, Aasa U. High load lifting exercise and low load motor control exercises as interventions for patients with mechanical low back pain: A randomized controlled trial with 24-month follow-up. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48(5):456-463.

- ↑ Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Wellman RD, et al. A randomized trial comparing yoga, stretching, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(22):2019-2026.

- ↑ Wewege MA, Booth J, Parmenter BJ. Aerobic vs. resistance exercise for chronic non-specific low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2018;31(5):889-899.

- ↑ American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Integrative Approaches to Therapeutic Exercise. Available from: https://now.aapmr.org/integrative-approaches-to-therapeutic-exercise-2/ (accessed 01/01/2022).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 National Institute of Health. oga: What You Need To Know. Available from: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/yoga-what-you-need-to-know (accessed 02/01/2022).

- ↑ Zhu F, Zhang M, Wang D, Hong Q, Zeng C, Chen W. Yoga compared to non-exercise or physical therapy exercise on pain, disability, and quality of life for patients with chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PloS one. 2020 Sep 1;15(9):e0238544.

- ↑ Kamioka H, Tsutani K, Katsumata Y, Yoshizaki T, Okuizumi H, Okada S, Park SJ, Kitayuguchi J, Abe T, Mutoh Y. Effectiveness of Pilates exercise: A quality evaluation and summary of systematic reviews based on randomized controlled trials. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2016 Apr 1;25:1-9.

- ↑ The Mayo Clinic. Tai chi: A gentle way to fight stress. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/in-depth/tai-chi/art-20045184 (accessed 02/01/2022).

- ↑ Qin J, Zhang Y, Wu L, He Z, Huang J, Tao J, Chen L. Effect of Tai Chi alone or as additional therapy on low back pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine. 2019 Sep;98(37).

- ↑ National Qigong Association. What is Qigong? Available from: https://www.nqa.org/what-is-qigong- (accessed 02/01/2022).

- ↑ Li H, Ge D, Liu S, et al. Baduanjin exercise for low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2019;43:109-116.

- ↑ Cattanach BK, Thorn BE, Ehde DM, Jensen MP, Day MA. A qualitative comparison of mindfulness meditation, cognitive therapy, and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for chronic low back pain. Rehabilitation psychology. 2021 Aug;66(3):317.

- ↑ Feldenkrais Mathod. Frequently asked questions. Available from: https://feldenkrais.com/feldenkrais-method-faqs/ (accessed 02/01/2022).

- ↑ Ahmadi H, Adib H, Selk-Ghaffari M, et al. Comparison of the effects of the Feldenkrais method versus core stability exercise in the management of chronic low back pain: a randomised control trial. Clin Rehabil. 2020;34(12):1449-1457.

- ↑ Alexander Technique. What is the Alexander Technique? Available from: https://alexandertechnique.com/at/ (accessed 02/01/2022).

- ↑ Little P, Lewith G, Webley F, Evans M, Beattie A, Middleton K, Barnett J, Ballard K, Oxford F, Smith P, Yardley L. Randomised controlled trial of Alexander technique lessons, exercise, and massage (ATEAM) for chronic and recurrent back pain. Bmj. 2008 Aug 19;337.