Femoral Neck Hip Fracture: Difference between revisions

(formatting) |

(formatting) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="noeditbox"> | |||

'''Original Editors ''' | '''Original Editors ''' | ||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

== Definition/Description == | == Definition/Description == | ||

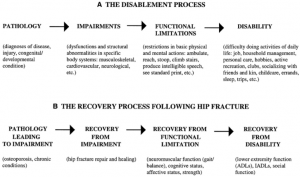

A hip fracture occurs when the proximal end of the femur, near the hip joint, is broken.About one-third of elderly people living independently fall every year, with 10% of these falls resulting in a hip fracture.<ref>Tinetti ME, Kumar C. The patient who falls: “It's always a trade-off. ''JAMA''. 2010 Jan 20;303(3):258–266.</ref> Such a fracture is a serious injury that occurs mostly in elderly people over 65 years and complications can be life-threatening.<ref name=":0" />(level of evidence 1A) The femur is the largest and strongest bone in the body, so it requires a large or high impact force to break. Most femur fractures are the result of a high energy trauma, such as a motor accident, gunshot wound, or jump/fall from a height.<ref name=":0" />However, in an older population, a simple fall may cause a femoral fracture due to reduced bone mineral density. A femoral fracture is a very serious injury and needs 3-6 months to heal.<ref name=":0" /> High mortality, long-term disability and huge socio-economic burden are the main consequences of a hip fracture. The biggest risk factors for running up a hip fracture are osteoporosis and cognitive impairment.<ref name=":0" /> | A hip fracture occurs when the proximal end of the femur, near the hip joint, is broken.About one-third of elderly people living independently fall every year, with 10% of these falls resulting in a hip fracture.<ref>Tinetti ME, Kumar C. The patient who falls: “It's always a trade-off. ''JAMA''. 2010 Jan 20;303(3):258–266.</ref> Such a fracture is a serious injury that occurs mostly in elderly people over 65 years and complications can be life-threatening.<ref name=":0">Antapur et al. Fractures in the elderly: when is a hip replacement a necessity? Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2011 (Level of evidence A1)</ref>(level of evidence 1A) The femur is the largest and strongest bone in the body, so it requires a large or high impact force to break. Most femur fractures are the result of a high energy trauma, such as a motor accident, gunshot wound, or jump/fall from a height.<ref name=":0" />However, in an older population, a simple fall may cause a femoral fracture due to reduced bone mineral density. A femoral fracture is a very serious injury and needs 3-6 months to heal.<ref name=":0" /> High mortality, long-term disability and huge socio-economic burden are the main consequences of a hip fracture. The biggest risk factors for running up a hip fracture are osteoporosis and cognitive impairment.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Revision as of 10:52, 27 February 2018

Original Editors

Top Contributors - Delmoitie Giovanni, Lucinda hampton, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Jessie Tourwe, Joyce De Gelas, Kim Jackson, Admin, Tolulope Adeniji, Aminat Abolade, Debontridder Jordy, Yarne Leuckx, Vidya Acharya, Annelies Beckers, Sara Evenepoel, Elien Lebuf, Karen Wilson, Claire Knott and Lauren Lopez

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

A hip fracture occurs when the proximal end of the femur, near the hip joint, is broken.About one-third of elderly people living independently fall every year, with 10% of these falls resulting in a hip fracture.[1] Such a fracture is a serious injury that occurs mostly in elderly people over 65 years and complications can be life-threatening.[2](level of evidence 1A) The femur is the largest and strongest bone in the body, so it requires a large or high impact force to break. Most femur fractures are the result of a high energy trauma, such as a motor accident, gunshot wound, or jump/fall from a height.[2]However, in an older population, a simple fall may cause a femoral fracture due to reduced bone mineral density. A femoral fracture is a very serious injury and needs 3-6 months to heal.[2] High mortality, long-term disability and huge socio-economic burden are the main consequences of a hip fracture. The biggest risk factors for running up a hip fracture are osteoporosis and cognitive impairment.[2]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The hip joint is a ball and socket joint, formed by the head of the femur and the acetabulum of the pelvis.

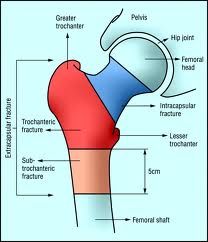

The head of the femur is almost ( for ¾ ) shaped like a sphere. The acetabulum is formed by the three parts of the os Coxae. It is a fusion of illium, ischium and pubis. Through this fusion, the acetabulum is shaped like a hemisphere (the inner section of a sphere) thereby the acetabulum is not covering the entire head of the femur.The convex head fits perfectly in the concave socket of the acetabulum forming a synovial joint. From an osteological viewpoint, the proximal end of the femur in four major parts, namely: femoral head, femoral neck, greater trochanter and the lesser trochanter. These parts are most often and most closely involved with hip fractures. The hip joint is a very sturdy joint, due to the tight fitting of the bones and the strong surrounding ligaments and muscles so a hip luxation will less likely take place. ce. ☃☃Hip fractures can be classified into intracapsular (femoral neck) fractures and extracapsular fractures. The intracapsular fractures are contained within the hip capsule itself. Those fractures are subcapital neck fracture and transcervical neck fracture. The extracapsular fractureans aran intertrochantericic and subtrochanteric fracture. You also have a greater and lesser trochantefracturees[3] (figure1)

Click Hip Anatomy for more details

Epidemiology [edit | edit source]

In 1990 there were estimated to be 1.66 million hip fractures around the world, and it’s also estimated that this number will rise to 6.26 million in 2050.

It is known that there will be more old people in 2050 than in 1990, this is the biggest cause of the big raise.[4]

Most of the hip fractures occur in North Europe and in the USA, the regions with the least hip fractures are Latin America and Africa. In Asia there is an immediate number of hip fractures. But it’s estimated that most of the hip fractures will occur in Asia by 2050.[5]

Age-standardized hip fracture rates (per 100 000 population) across different continents[5]

|

Continent |

Country |

Men |

Women |

|

Africa |

|

|

|

|

|

Rabat |

57.7 |

79.9 |

|

|

Cameroon |

43.7 |

52.1 |

|

Asia |

|

|

|

|

|

Beijing |

87 |

97 |

|

|

Shenyang |

101.3 |

80.9 |

|

|

Korea |

137 |

262 |

|

|

Iran |

127.3 |

164.6 |

|

|

Malaysia |

87.4 |

212.5 |

|

|

Tottori |

107.3 |

297.3 |

|

|

Japan |

99.6 |

368 |

|

|

Kuwait |

216.6 |

316 |

|

|

Singapore |

152 |

402 |

|

|

Hong Kong |

193 |

484.3 |

|

|

Hong Kong |

50 |

110 |

|

|

Taiwan |

233.4 |

496.8 |

|

South America |

|

|

|

|

|

Mexico |

98 |

169 |

|

|

Sobral, Brazil |

59.3 |

168.4 |

|

|

Argentina |

137 |

405 |

|

|

Venezuela |

37 |

98 |

|

Europe |

|

|

|

|

|

Switzeland |

137.8 |

346 |

|

|

Former East Germany |

137.8 |

354.7 |

|

|

Former West Germany |

154.5 |

399.4 |

|

|

England |

143.6 |

418.2 |

|

|

Greece |

201.7 |

469.9 |

|

|

Sweden |

302.7 |

709.5 |

|

|

Norway |

352 |

763.6 |

|

|

Oslo |

399.3 |

920.7 |

|

|

Austria |

567 |

759 |

|

|

Hungary |

223 |

430 |

|

|

The Nederlands |

308 |

669 |

|

North America |

|

|

|

|

|

Minnesota |

201.6 |

511.6 |

|

|

United States |

197 |

516 |

|

Oceania |

|

|

|

|

|

Maori, New Zealand |

197 |

516 |

|

|

Non-Maori |

288 |

827 |

|

|

New South Wales |

191.8 |

475.1 |

|

|

Australia |

187.8 |

504.2 |

Classification of Hip Fractures[edit | edit source]

Hip fractures can be classified into intracapsular and extracapsular fractures[6] (figure2).

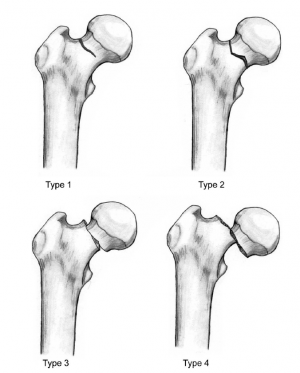

1) Intracapsular fractures: also known as femoral neck fractures. It occurs within the hip capsule and accounts for 45% of all acute hip fractures in the elderly.[7] It mostly results from a low-impact fall from a standing position or from twisting on a planted foot.[8] Femoral neck fractures are susceptible to malunion and avascular necrosis of the femoral head because of the limited blood supply to the area. Intracapsular fractures are further classified as nondisplaced or displaced based on radiographic findings[9] (figure 3).

- Type 1: undisplaced and incomplete fracture

- Type 2: undisplaced complete fracture

- Type 3: complete fracture but incompletely displaced

- Type 4: complete fracture and completely displaced

2) Extracapsular fractures: could be an intertrochanteric fracture or subtronchanteric fracture.

- Intertrochanteric fracture: occurs between the greater and the lesser trochanter.[6] Majorly occurs in the osteoporotic geriatric population and result from a fall from a standing height with direct contact of the lateral thigh or torsion of the lower extremity. The intertrochanteric region has a good blood supply, avascular necrosis or nonunion is rare.

- Subtronchanteric fracture: occurs below the lesser trochanter, approximately 2.5 inches below

About 3% of hip fractures are related to localized bone weakness at the fracture site, secondary to tumor, followed by bone cysts, or Paget’s disease. More than half of the remaining patients have osteoporosis, and nearly all are osteopenia[10]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

A substantial portion of the population is at risk of hip fracture by virtue of low bone mass and frequent falls.[11] Fracture incidence rates rise dramatically with age, and populations are aging rapidly around the world. Due to the sheer size of the affected population, control programs for osteoporosis are likely to be expensive, but effective and efficient prevention efforts have great potential promise.The incidence rates themselves are rising in some regions, and any further improvements in life expectancy will compound the problem.[11]

- Trauma or lesion in the femur ( around 10% )[12]

- Local pathologies ( 1% ); metastatic malignancy

- Fall

- Hip fractures without injuries ( < 5% )

- Osteoporosis: Osteoporosis is a multifactorial, chronic disease that may progress silently for decades until characteristic fractures occur late in life.

Risk factors[edit | edit source]

Risk factors for hip fracture include[13][14]:

- Gender: prevalent in women; postmenopausal twice as likely as premenopausal to have hip fracture[15]

- Reduced Bone density[16]

- Fall

- Medications: Some medications can cause a decrease in bone density like cortisone.

- Nutrition: It is well known that calcium and vitamin D increase bone mass, so a lack of it can cause several fractures, including hip fractures. Some eating disorders like anorexia and bulimia can weaken your bones, zo you become more fragile to have a hip fracture.

- Age: the older you get, the higher the risk is for hip fractures. 90% of these fractures occur in persons over 70 years old.

- Alcohol and tobacco: These products can reduce the bone mass, causing a higher risk to have a hip fracture

- Medical problems: Endocrine disorders can cause fragility of the bones

- Physical inactivity: Physical activity is very important for the muscle mass and the bone mass, so if you practice enough sports you will have less risk to have hip fractures.

- Stroke disease increases risk factor for falls which can cause a hip fracture.

- Parkinson’s disease increases risk factor for falls which can cause a hip fracture.

Risk factors other than low bone mineral density (BMD), defined by the National Osteoporosis Foundation (National Osteoporosis Foundation, 1998) are previous history of fracture as an adult, history of fracture in a first-degree relative, low body weight, and current cigarette smoking.[17]Another risk factor that is frequently discussed for the last years is the proximal femoral geometry, it is suggested as an important marker for the hip fracture risks.[17]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Specific features for patients with hip fracture include:[10][11]

- Dull ache in the groin and/or hip region [12] (level of evidence B)

- Inability to put weight on the injured leg causing immobility right after the fall [13] (level of evidence A1)

- If the femur bone is completely broken the injured leg might be shorter compared to the other leg

- Severe pain

- The patient tends to keep the injured hip as still as possible, positioning it in external rotation [13]

- A swelling might occur

- Patients may not be able to achieve the same level of functional recovery as their cognitively intact counterparts do

- Intertrochanteric Fractures, subcapital fractures, subtrochanteric fractures, cervical fractures, fracture of the acetabulum, posterior fracture (femoral neck fracture / fracture of superior or inferior ramus of pubis) + hip dislocation

The most frequent fractures are the subcapital fractures (especially by decreasing bone density in osteoporosis) and intertrochanteric fractures.

There are two types of fractures: intra- and extra capsular fractures.

Intra capsular = femoral neck / cervical

Extra capsular = intertrochanteric / pertrochanteric / subtrochanteric

Signs and symptoms of a hip fracture include:

- Inability to move immediately after a fall [4]

- Severe pain in your hip or groin [4]

- Inability to put weight on your leg on the side of your injured hip [4]

- Stiffness, bruising and swelling in and around your hip area [4]

- Shorter leg on the side of your injured hip [4]

- Turning outward of your leg on the side of your injured hip [4]

- During the physical examination, displaced fractures present with external rotation and abduction, and the leg will appear shortened. [5] (level of evidence C2)

- Patients with hip fractures have pain in the groin and are unable to bear weight on the affected extremity [5]

- During the physical examination, displaced fractures present with external rotation and abduction, and the leg will appear shortened [5]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Femoral Head Avascular Necrosis

- Femoral Neck Fracture

- Femoral Neck Stress Fracture

- Femur Injuries and Fractures

- Hip Pointer

- Hip Tendonitis and Bursitis

- Iliopsoas Tendinitis

- Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

- Hip dislocation

- Pelvic fracture

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis of a hip fracture is established based on patient history, physical examination, and radiography.[18] The majority of hip fractures are found by plain radiography, the initial imaging modality used in the diagnosis of hip fracture, which has a sensitivity ranging from 90%-95%.[19][20][21][22] Occult hip fractures are not detectable by radiography, MRI has been shown to have 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity in diagnosing occult hip fractures. Standard x-ray examination of the hip includes an anteroposterior (AP) view of the pelvis and an AP and cross-table lateral view of the involved hip. Plain x-rays without evidence of fracture do not exclude the diagnosis of hip fracture.

If MRI is contraindicated, bone scan is an alternative imaging option. Bone scans have a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 95% in detecting occult hip fractures.[23]CT scan is another modality that can be used to diagnose occult hip fractures, although its efficacy has been proven by few studies.[24]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Functional Independence Measure: ability to walk and to climb stairs can be measured with a subscale of the FIM. It is a predictor for locomotion This test rates the patient's independence in traveling 45 m (150 ft) walking or in a wheelchair and in going up and down 12 to 14 stairs. A higher score on the test represents a better locomotion. Age and prefracture residence at a nursing home were significant predictors of locomotion (P = .02 for both[25]). (Level of evidence A2)

- International Hip Outcome Tool (iHOT): The test consists of 33 questions that relate to Symptoms and Functional Limitations, Sports and Recreational Activities, Job-Related Concerns, Social, Emotional, and Lifestyle Concerns.

iHOT is one of the most carefully and comprehensively validated outcome measures in orthopaedic surgery. Each question has a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) line where the patient has to put on a marker. The total score is a calculation of the mean of all VAS scores measured in millimeters.

- Cumulated Ambulation Score (CAS) is a valid tool to evaluate the basic mobility from patients with hip fracture. The test is highly recommended after hip fractures to test the basic mobility. Certainly recommended for hospital treatments.

- Timed Up and Go Test (TUGT) is used to test the functional mobility level.The test consists in rising from a chair, walk 3 meters on a straight line, turn around and go back to the chair and sit down. When the time is less than 10 seconds, it indicates a normal mobility. Between 11-20 seconds are normal limits for frail elderly and disabled patients but for others it’s an indication for examination and has a higher fall risk. Greater than 20 seconds, there is need to further examination and intervention.

http://www.physio-pedia.com/Timed_Up_and_Go_Test_(TUG)

- Chair Stand- Test The amount of time it takes to rise and sit back from a chair or the number of times someone can rise from a chair in 30 seconds.

The test was performed with the person sitting on a chair (height 45 cm) without arms, but a chair with arms was used if the patient was unable to stand without the use of the armrests. The patient was instructed to stand and sit from a seated position as many times as possible within 30 seconds.

Early surgery was not associated with improved function and increased mortality. Though it was associated with reduced pain and length of stay. Early surgery also resulted in fewer complications. These conclusions were obtained by comparing patients having surgery within 24 hours with those having surgery after 24 hours on the following outcomes: [21] (Level of Evidence A2)

- Mean pain scores over the first 5 hospital days;

- Number of days of severe and very severe pain over hospital days 1 to 5 (assessed by asking patients if they were experiencing no pain, or mild, moderate, or severe pain);

- Major postoperative complications;

- LOS;

- mortality through 6 months;

- FIM locomotion (a 2-item subscale focusing on walking and climbing stairs) score at 6 months;

- FIM self-care (a 6-item scale of self-care activities including bathing and dressing); and

- FIM transferring (a 3-item scale focusing on transfers from the bed, toilet, and tub).[21] (Level of Evidence A2)

In the study of Diamond TH et al. are the main outcome measures Prognostic factors (such as pre-existing illness and osteoporotic risk factors) and outcome data (such as fracture-related complications, mortality, and level of function as measured by the Barthel index of activities of daily living at six and 12 months postfracture).

The results of these outcome measures are that fracture-related complications affected similar proportions of men and women (30% v. 32%), and mean length of hospital stay was similar. Fourteen per cent of men died in hospital compared with only 6% of women (P = 0.06). Men had more risk factors for osteoporosis (P < 0.01). [22] (Level of evidence C)

Physical functioning (measured by the Barthel index) deteriorated significantly in men from 14.9 at baseline to 13.4 at six months (P < 0.05) and 12.4 at 12 months (P < 0.05) after fracture.[22] (Level of evidence C)

Jay Magaziner et al. investigated eight areas of function after hip fracture. This eight areas of function (i.e., upper and lower extremity physical and instrumental activities of daily living; gait and balance; social, cognitive, and affective function) were measured by personal interview and direct observation during hospitalization at 2, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months.

Levels of recovery are described in each area, and time to reach maximal recovery was estimated using Generalized Estimating Equations and longitudinal data.

Most areas of functioning showed progressive lessening of dependence over the first postfracture year, with different levels of recovery and time to maximum levels observed for each area. New dependency in physical and instrumental tasks for those not requiring equipment or human assistance prefracture ranged from as low as 20.3% for putting on pants to as high as 89.9% for climbing five stairs.

Recuperation times were specific to area of function, ranging from approximately 4 months for depressive symptoms (3.9 months), upper extremity function (4.3 months), and cognition (4.4 months) to almost a year for lower extremity function (11.2 months) [23]

(Level of evidence C)

Physical Examination[edit | edit source]

On physical examination, findings on the patient with a hip fracture may include the following:

- limited and painful hip range of motion, especially in internal rotation.

- the injured leg is shortened, externally rotated, and abducted in the supine position

- Pain is noted upon attempted passive hip motion.

- Ecchymosis may or may not be present.

- An antalgic gait pattern may be present.

- Tenderness to palpation around the inguinal area, over the femoral neck. This area may also be swollen.

- Increased pain on the extremes of hip rotation, an abduction lurch, and an inability to stand on the involved leg

For more on Hip examination, click www.physio-pedia.com/Hip_Examination

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

The principal goals of management are a return to a pre-event functional level and the prevention of recurrent fractures, 50% of survivors fail to regain their former levels of autonomy and mobility. There are many different kinds of operations and treatments if we talk about hip fracture. The sort of operation or treatment that is used is based on the sort of fracture and personal factors. [16]

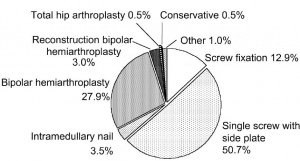

In the previously used source (16) almost 80% of the subcapital fractures were treated with a cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty. All but one of the undisplaced subcapital fractures were treated with screw fixation. [16]

Half of the hip fractures were treated with a dynamic hip screw. This represents 87.2% of the fractures in the trochanteric region. Intramedullary nailing was used in less than 4% of the cases. [16]

Cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasties with diaphy- seal support were implanted in six patients with complex inter- or subtrochanteric fractures. [16]

One stable undisplaced subcapital fracture was treated conservatively. (2)

In figure 4 you can find an overview of different type of treatment performed for a hip fracture.[16]

General treatment options:

• External fixation – An external frame design is a rectangular construct mounted on two to three pins, 1cm distance from each other along the anterior iliac crest.

Postoperative plan for immobilization:

Lateral compression: external fixation for 3 to 6 weeks is advised. With mobilization depending on the comorbid injuries

Anteroposterior compression: external fixation for 8-12 weeks, depending on the principle of the posterior sacroiliac ligaments.

Vertical shear: external fixation for 12 weeks with mobilization leaded by radiographic evidence of healing. This may require combination with open reduction and internal fixation for adequate stabilization.

•Internal fixation – this significantly rises the forces resisted by the pelvic ring when compared to external fixation. Biomechanical studies suggest the following treatments:

Iliac wing fractures: open reduction and internal fixation

Diastasis of the pubic symphysis: plate fixation if undergoing laparotomy

Sacral fractures: transiliac bar fixation, but may cause compressive neurologic injury

Unilateral sacroiliac dislocation: internal fixation with cancellous screws fixation can be indicated

Bilateral posterior unstable disruptions: fixation of the displaced part of the pelvis to the sacral body may be accomplished by posterior screw fixation.

• Open fractures: priority should be given to the evaluation of the anus, rectum, vagina and genitourinary system.

• Postoperative plan: Generally, early mobilization is desired

Intracapsular Fractures:

Surgical management is the treatment of choice for the majority of femoral neck fractures, but treatment for non-displaced femoral neck fractures can be non-operative. Non-operative treatment involves protected weight bearing with crutches for 6 weeks. Non-operative repair is usually reserved for patients who present late after a fracture or who have significant comorbidities and a high operative risk.[3]

The treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures is more complex, and surgical repair is usually the treatment of choice. These fractures are not amenable to non-operative management, which should be reserved for patients with extremely high surgical risk or non-ambulatory elderly patients with dementia and very limited life expectancies.[3]

Extracapsular Fractures:

Surgical stabilization is standard treatment, and non-operative measures are only considered for patients who are deemed at very high surgical risk or who have a limited life expectancy. The goal of surgery is to achieve a stable fracture reduction and fixation, allowing early weight bearing and mobilization of the patient. Non-operative management is only considered for non-ambulatory patients with minimal pain and for medically unstable patients with major un-correctable comorbid disease or terminal illness.[3]

Delirium may be the most common medical complication after hip fracture. Delirium may interfere with recovery and rehabilitation, increase duration of hospitalization, and increase mortality after one year.[26]Common precipitating factors include electrolyte and metabolic abnormalities, inadequate pain control, infection, and psychoactive medications. Physicians can help prevent delirium by avoiding polypharmacy, minimizing the use of anticholinergic and psychoactive medications, removing urinary catheters and intravenous lines as soon as possible, and minimizing sleep interruptions.

If delirium occurs, a thorough evaluation and treatment of the underlying cause is needed. Patients who do not respond to conservative measures may benefit from low-dose tranquilizers (e.g., haloperidol [Haldol) or atypical antipsychotics (e.g., risperidone [Risperdal], olanzapine [Zyprexa]). These agents should be discontinued as soon as possible after the delirium is resolved[26]

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Prolonged bed rest can increase the risk of pressure sores, atelectasis, pneumonia, deconditioning, and thromboembolic complications. Weight bearing immediately after hip fracture surgery is safe in most patients.[26](Level of evidence 2A)

Within two years of a hip fracture, more than half of men and 40% of women are either dead or living in a long-term care facility.

The sooner you return to daily physical tasks after surgery or being injured, the healthier you’ll be . “Complications following hip surgery involve blood clots, pneumonia, wound infections, and more, all of which can be reduced with activity[27] [27](Level of evidence 2A)

There are some important rules postoperative:

- internal rotation from hip flexion is very stressful for the joint

- impact activities should be avoided for six weeks postoperative

- depending on the surgical procedure is unloaded or partially loaded mobilize postoperatively crucial to the joint

- Avoid straight leg raise for 4 weeks postoperatively to not provoke irritation of the nerve

- Cardiovascular training is important

Prolonged bed rust can increase the risk of pressure sores and deconditioning. Therefore it’s important to start rehabilitation on the first post-operative day (on patients with a total hip replacement). This includes quadriceps strengthening exercises, isometric exercises, and flexion and extension mobilizations in the hip joint …[13](Level of evidence 3B)

On the second and third post-operative day the patient can start with walking between parallel bars, and later on they can walk with a walker or a cane. This walking is supervised.

The physiotherapist will begin with range of motion exercises for the hip, knee and ankle because mobility is decreased following immobilization. Mobilization is a very important treatment in the recovery process.

The patient can also begin strengthening exercises based on the surgeon's orders (typically six weeks post-op). Patients should also undergo balance and proprioceptive rehab and these abilities are quickly lost with inactivity.[28]

Weight-bearing exercises are very important for mobility, balance, activities of daily living and quality of life[5](Level of evidence 2C), examples:

- Stepping in different directions

- Standing up and sitting down

- Tapping the foot and stepping onto and off a block.

It is ordinarily suggested that patients who underwent a prosthetic replacement have to avoid for approximately 12 weeks:[24] (Level of evidence 5)

- Hip flexion greater than 70–90°

- External rotation of the leg

- Adduction of the leg past midline

- Should not bend forward from the waist more than 90

The patient training begins the day after surgery from a sitting position, with abducted hip during transfer from bed to chair.[24](Level of evidence 5)

Progressive weight-bearing as tolerated till full weight-bearing should start soon after surgery according to general physical status.[24](Level of evidence 5)

When internal fixation is performed, partial weight-bearing is recommended for a period of 8–10 weeks (according to the radiological evaluation of fracture healing), and after 3 months full weight-bearing should be allowed.[24](Level of evidence 5)

A warming up on a stationary bicycle for 10 to 15 minutes is recommended.[25](Level of evidence 2A)

Among patients who had completed standard rehabilitation after hip fracture, the use of a home-based functionally oriented exercise program resulted in modest improvement in physical function at 6 months after randomization.[26] (Level of evidence 1B)

Program components[28](Level of evidence 1B):

- Hip extension (theraband and manual exercise)

- Heel raises onto toes (theraband and manual exercise)

- Resisted rowing (double arm lifting) (theraband and manual exercise)

- Standing diagonal reach (theraband and manual exercise)

- Modified get up and go (theraband and manual exercise)

- Overhead arm extensions (theraband and manual exercise)

- Repeated chair stands (vest and manual exercise)

- Lunges - forward and back (vest and manual exercise)

- Stepping up and down step (vest, manual exercise and plyometric step)

- Calf raises - both legs and one leg (manual exercise)

Twelve weeks of progressive strength training once a week, as a follow-up to a more intensive training period after hip fracture has no measureable effect upon the BBS (Berg Balance Scale) score, but may improve strength, endurance, self-reported NEADL (The Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living score), and self-perceived health.

Home-dwelling hip fracture patients seem to constitute a group that needs prolonged follow-up to achieve the improvements that are important for independent functioning.[25](Level of evidence 2A)

Prevention is also a part of the rehabilitation process to prevent fractures. Prevention of hip fractures should focus on preventing falls and osteoporosis.

Several strategies could help reduce the loss of bone density that underlies hip fracture. Among these, a substantial body of evidence indicates that physical activity is the most important, and it is a method of prevention that can be enjoyable and sociable.

Regular exercise would reduce the risk of hip fracture by at least half.

Stopping smoking is also important, and a woman who stops smoking before the menopause will reduce her risk by about a quarter. [29](Level of evidence 2A)

Both these policies can be adopted by both sexes and continued into old age. Postmenopausal oestrogen replacement more than halves the risk of hip fracture, but the loss of this protection within a few years of stopping treatment limits its utility.

Oestrogen replacement would need to be continued almost indefinitely if it were to do more than reduce the incidence of hip fracture in younger age groups, in whom hip fracture is uncommon and recovery generally uncomplicated. General calcium supplementation is not justified as the likely benefit is too small.[29](Level of evidence 2A)

Interventions to reduce the risk of falls should target identified risk factors (e.g., muscle weakness; history of falls; use of four or more prescription medications; use of an assistive device; arthritis; depression; age older than 80 years; impairments in gait, balance, cognition, vision, or activities of daily living).(26)(Level of evidence 1B)

Resources

[edit | edit source]

http://www.sint-trudo.be/downloads/Behandeling%20heupfracturen.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hip_fracture

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hip_replacement

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

The number of hip fractures worldwide will increase up to 7-21 million incidences each year in 2050.[29] Mortality associated with a hip fracture is about 5-10% after one month. One year after fracture, about a third of patients will have died, compared with an expected annual mortality of about 10% in this age group.[29]

Thus, only a third of the deaths are directly attributable to the hip fracture itself, but patients and relatives often think that the fracture has played a crucial part in the final illness. More than 10% of survivors will be unable to return to their previous residence. Most of the remainder will have some residual pain or disability. Most people who sustain the injury require surgery followed by a period of rehabilitation.Treatment is generally surgical to replace or repair the broken bone.

Some loss of function is to be expected in most patients.

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

http://www.physio-pedia.com/Diagnostic_Imaging_of_the_Hip_for_Physical_Therapists

http://www.physio-pedia.com/Acetabulum_fracture

http://www.physio-pedia.com/Femur

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.ezproxy.vub.ac.be:2048/doi/10.1002/pds.3863/full

https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12891-016-0988-9

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Tinetti ME, Kumar C. The patient who falls: “It's always a trade-off. JAMA. 2010 Jan 20;303(3):258–266.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Antapur et al. Fractures in the elderly: when is a hip replacement a necessity? Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2011 (Level of evidence A1)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Bateman, Laura, et al. "Medical management in the acute hip fracture patient: a comprehensive review for the internist." The Ochsner Journal 12.2 (2012): 101-110. (Level of Evidence B2)

- ↑ Kannus, P., et al. "Epidemiology of hip fractures." Bone 18.1 (1996): S57-S63. (level of evidence 2A)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Dhanwal, Dinesh K., et al. "Epidemiology of hip fracture: Worldwide geographic variation." Indian journal of orthopaedics 45.1 (2011): 15. (level of evidence 2A)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Zuckerman JD. Hip fracture. N Engl J Med. 1996 Jun 6;334(23):1519–1525.

- ↑ Canale ST. Campbell's Operative Orthopaedics. St. Louis, MO: Mosby;; 1998. pp. 2181–2223.

- ↑ Christodoulou NA, Dretakis EK. Significance of muscular disturbances in the localization of fractures of the proximal femur. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984. pp. 215–217. Jul-Aug. (187)

- ↑ Garden RS. The structure and function of the proximal end of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1961 Aug;43B(3):576–589.

- ↑ Rao, Shobha S., and Manjula Cherukuri. "Management of hip fracture: the family physician’s role." Am Fam Physician 73.12 (2006): 2195-2200. (level of evidence 2A)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Melton, LJd. "Hip fractures: a worldwide problem today and tomorrow." Bone 14 (1993): 1-8. (level of evidence 2A)

- ↑ Melton, LJd. "Hip fractures: a worldwide problem today and tomorrow." Bone 14 (1993): 1-8. (level of evidence 2A)

- ↑ Grisso, Jeane Ann, et al. "Risk factors for falls as a cause of hip fracture in women." New England Journal of Medicine 324.19 (1991) (level of evidence 2A)

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/hip-fracture/DS00185/DSECTION=risk-factors (visited on april 2016)

- ↑ Banks E, Reeves GK, Beral V, Balkwill A, Liu B Roddam A. Million Women Study Collaborators. Hip fracture incidence in relation to age, menopausal status, and age at menopause: prospective analysis. PLoS Med. 2009 Nov;6(11) e1000181. Epub 2009 Nov 1.

- ↑ Angthong C, Suntharapa T, Harnroongroj T. [Major risk factors for the second contralateral hip fracture in the elderly] Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2009 May-Jul;43(3):193–198. Turkish.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Parker, Martyn, and Antony Johansen. "Hip fracture." British Medical Journal 7557 (2006): 27. (Level of Evidence A3)

- ↑ Dinçel, V. Ercan, et al. "The association of proximal femur geometry with hip fracture risk." Clinical Anatomy 21.6 (2008): 575-580. (Level of Evidence B3)

- ↑ Dominguez S, Liu P, Roberts C, Mandell M, Richman PB. Prevalence of traumatic hip and pelvic fractures in patients with suspected hip fracture and negative initial standard radiographs—a study of emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2005 Apr;12(4):366–369.

- ↑ Lee YP, Griffith JF, Antonio GE, Tang N, Leung KS. Early magnetic resonance imaging of radiographically occult osteoporotic fractures of the femoral neck. Hong Kong Med J. 2004 Aug;10(4):271–275.

- ↑ Lim KB, Eng AK, Chng SM, Tan AG, Thoo FL, Low CO. Limited magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and the occult hip fracture. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2002 Sep;31(5):607–610.

- ↑ Kirby MW, Spritzer C. Radiographic detection of hip and pelvic fractures in the emergency department. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010 Apr;194(4):1054–1060

- ↑ Holder LE, Schwarz C, Wernicke PG, Michael RH. Radionuclide bone imaging in the early detection of fractures of the proximal femur (hip): multifactorial analysis. Radiology. 1990 Feb;174(2):509–515.

- ↑ Cannon J, Silvestri S, Munro M. Imaging choices in occult hip fracture. J Emerg Med. 2009 Aug;37(2):144–152. Epub 2008 Oct 28. [

- ↑ Edward l Hannan et al., Mortality and Locomotion 6 Months After Hospitalization for Hip FractureRisk Factors and Risk-Adjusted Hospital Outcomes (Level of Evidence A2)

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Scheerlinck, T., et al. "Hip fracture treatment: outcome and socio-economic aspects: a one-year survey in a Belgian university hospital." Acta orthopaedica belgica 69.2 (2003): 145-156(level of evidence 2A)

- ↑ Daniel Pendick. ‘’After hip fracture, exercise at home boosts day-to-day function’’ Harvard health publication (2014) (level of evidence 2A)

- ↑ Latham, Nancy K., et al. "Effect of a home-based exercise program on functional recovery following rehabilitation after hip fracture: a randomized clinical trial." Jama 311.7 (2014): 700-708. (Level of evidence B1)

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Kannus, P., et al. "Epidemiology of hip fractures." Bone 18.1 (1996): S57-S63. (level of evidence 2A)