Ober's Test: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

*If the ITB is normal, the leg will adduct with the thigh dropping down slightly below the horizontal and the patient won't experience any pain; in this case, the test is called negative. | *If the ITB is normal, the leg will adduct with the thigh dropping down slightly below the horizontal and the patient won't experience any pain; in this case, the test is called negative. | ||

*If the ITB is tight, the leg would remain in the abducted position and the patient would experience lateral knee pain, in this case, the test is called positive.<br> <br> | *If the ITB is tight, the leg would remain in the abducted position and the patient would experience lateral knee pain, in this case, the test is called positive.<br> <br> | ||

{| width="100%" cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" | {| width="100%" cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" | ||

Revision as of 06:55, 29 July 2018

Original Editor - Nicole Kluckhohn, Agapi Hakobyan

Top Contributors - Vidya Acharya, Agapi Hakobyan, Admin, Paige Canada, Madison Hagen, Nicole Kluckhohn, Ben Kasehagen, Tony Varela, Victoria Morris, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Merlin Roggeman, Tony Lowe, Tarina van der Stockt, Chrysolite Jyothi Kommu, Kai A. Sigel, Wanda van Niekerk, Oyemi Sillo and Sweta Christian

Description[edit | edit source]

Purpose[edit | edit source]

The Ober's test evaluates a tight, contracted or inflamed Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL) and Iliotibial band (ITB). The Ober’s test must not be confounded with Noble’s test and the Renne test, two other tests that are commonly used to detect iliotibial band syndrome.

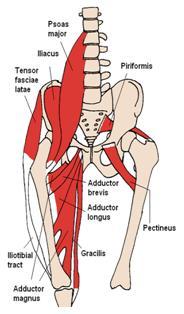

Anatomically, the ITB is a continuation of the tendinous portion of the Tensor Fascia Latae (TFL) muscle with some contributions from the gluteal muscles. TFL/ITB is a synergist of gluteus medius muscle in hip abduction[1].

Origin:[edit | edit source]

The TFL originates[2] from: the anterior part of the external lip of iliac crest, the outer surface of an anterior superior iliac spine and deep surface of fascia lata.

The Iliotibial band (ITB) or tract is a lateral thickening of the fascia lata in the thigh[3]. Proximally it splits into superficial and deep layers, enclosing tensor fasciae latae and anchoring this muscle to the iliac crest. It also receives most of the tendon of gluteus maximus.

The ITB originates from:

- the external lip of the anterior iliac crest

- anterior border of the ilium spine

- the outer surface of the anterior superior iliac spine

Insertion:[edit | edit source]

The TFL inserts[2] into the ITB at the anterolateral thigh at the junction of proximal and middle thirds of the thigh.

The ITB is generally viewed as a band of dense fibrous connective tissue that passes over the lateral femoral epicondyle and attaches to Gerdy's tubercle[3] on the anterolateral aspect of the tibia.

For the stabilization of the knee, it helps to expanse the lateral collateral ligament and posterolateral joint capsule.

Action:[edit | edit source]

TFL flexes, medially rotates and abducts the hip joint; tenses the fascia lata; and may assist in knee extension[2]. Gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and upper fibres of the gluteus maximus are the primary synergistic muscles of the hip abductors.

Technique[edit | edit source]

- The patient should be in side-lying with the affected side up.

- Bottom knee and hip should be flexed to flatten the lumbar curve.

- Stand behind the patient and firmly stabilize the pelvis/greater trochanter to prevent movement in any direction.

- Grasp the distal end of the patient’s affected leg with your other hand and flex the leg to a right angle at the knee

- For consistency in testing, some suggest using top hand and arm to be placed under the flexed knee holding onto the side of the table. Note the angle of the hip and knee which should be near 90/90. This may allow for better reproduction for future testing

Test:

- Extend and Abduct the hip joint.

- Slowly lower the leg toward the table -adduct hip- until motion is restricted.

- Ensure that the hip does not internally rotate and flex during the test and the pelvis must be stabilized. As allowing the thigh to drop in flexion and internal rotation would give in to the tight TFL and not accurately test the length.

Frank Ober in his article "Back Strain and Sciatica" dated on May 4 1935 discussed the relationship of low backache and sciatica with contracted TFL and ITB. He described the Ober test (Abduction test) in that article. Henry O Kendall raised a concern about this test that allowing the thigh to drop in flexion and internal rotation would give in to the tight TFL and not accurately test the length.

Results:

- If the ITB is normal, the leg will adduct with the thigh dropping down slightly below the horizontal and the patient won't experience any pain; in this case, the test is called negative.

- If the ITB is tight, the leg would remain in the abducted position and the patient would experience lateral knee pain, in this case, the test is called positive.

| [6] | [7] |

Evidence[edit | edit source]

There is a limited number of studies to support the validity of this test.

A study by Reese et al shows that the use of an inclinometer to measure hip adduction using both the Ober test and the modified Ober test appears to be a reliable method for the measurement of IT band flexibility, and the technique is quite easy to use. It demonstrated a significant difference in ROM between testing with the affected knee flexed vs. extended, with the reliability of .90 and .91 respectively[8]. The modified Ober test allows significantly greater hip adduction range of motion than the Ober test, the 2 examination procedures should not be used interchangeably for the measurement of the flexibility of the IT band.

But the study[9] findings by Willet GM et al refutes the hypothesis that the ITB plays a role in limiting hip adduction during either version of the Ober test and question the validity of these tests for determining ITB tightness. The findings underscore the influence of the gluteus medius and minimus muscles as well as the hip joint capsule on Ober test findings. The results of this study suggest that the Ober test assesses tightness of structures proximal to the hip joint, such as the gluteus medius and minimus muscles and the hip joint capsule, rather than the ITB.

Key Research[edit | edit source]

- The study in Clinical Biomechanics by Gajdosik RL et al showed the hip adduction movement was restricted more with the knee flexed than with the knee extended for both genders (P<0.009). With the knee flexed the mean hip abduction angle was less for men (+4 degrees) than for women (+6 degrees) (P<0.001), and with the knee extended the mean hip adduction angle was greater for men (-9 degrees) than for women (-4 degrees) (P<0.001). Thus emphasizing the influence of knee positions and gender on the Ober test for length of the iliotibial band[10].

- An exercise developed by the Postural Restoration Institute to recruit hamstrings and abdominal muscles showed a significant increase in passive hip-adduction angles (p<0.01) and a decrease in pain (p<0.01), immediately improve Ober's Test measurements in people with lumbopelvic pain. The study[11] showed hamstring/abdominal activation, rather than iliotibial band stretching, may be an effective intervention for addressing lumbopelvic pain and a positive Ober's Test.

- Effect of Iliotibial Band stretching versus Hamstrings and Abdominal muscle activation on a positive Ober’s test in subjects with Lumbopelvic Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial by Vijay Kage, Saitej Kolukula Naidu; July 2015 https://www.ejmanager.com/mnstemps/12/12-1435370486.pdf

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

If the patients have iliotibial band syndrome and there is a doubt about the diagnosis, MRI can help to confirm the diagnosis by giving additional information about patients who can be considered for surgery. MRI illustrates a thickened iliotibial band over the lateral femoral epicondyle and frequently detects a fluid collection deep into the iliotibial band.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Arab AM, Nourbakhsh MR. The relationship between hip abductor muscle strength and iliotibial band tightness in individuals with low back pain. Chiropractic & osteopathy. 2010 Dec;18(1):1.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2821316/ (accessed on 25/07/18)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Kendall, McCreary, Provance; Muscle Testing and Function with Posture and Pain 4th Edition; Tensor Fascia Latae; Page No.216

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Fairclough J, Hayashi K, Toumi H, Lyons K, Bydder G, Phillips N, Best TM, Benjamin M. The functional anatomy of the iliotibial band during flexion and extension of the knee: implications for understanding iliotibial band syndrome. Journal of Anatomy. 2006 Mar;208(3):309-16.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2100245/ (accessed on 25/07/2018)

- ↑ Magee D. Orthopedic Physical Assessment. 2nd ed.Pennsylvania:WB Saunders, 1992. p354-355

- ↑ Hoppenfeld S. Physical Examination of the spine and Extremeities. London: Prentice-Hall International 1976.p167

- ↑ Physiotutors.Ober's Test⎟ Iliotibial Band Tightness. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Amjv6FzDeLE

- ↑ bigesor Ober's Test Available from

- ↑ Reese NB, Bandy WD. Use of an inclinometer to measure flexibility of the iliotibial band using the Ober test and the modified Ober test: differences in magnitude and reliability of measurements. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2003 Jun;33(6):326-30.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12839207 (accessed on 28/07/2018)

- ↑ Willett GM, Keim SA, Shostrom VK, Lomneth CS. An anatomic investigation of the Ober test. The American journal of sports medicine. 2016 Mar;44(3):696-701.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26755689 accessed on 28/07/2018

- ↑ Gajdosik RL, Sandler MM, Marr HL. Influence of knee positions and gender on the Ober test for length of the iliotibial band. Clinical biomechanics. 2003 Jan 1;18(1):77-9.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12527250 (accessed on 28/07/2018)

- ↑ Tenney HR, Boyle KL, DeBord A. Influence of hamstring and abdominal muscle activation on a positive Ober's test in people with lumbopelvic pain. Physiotherapy Canada. 2013 Jan;65(1):4-11.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3563370/ (accessed on 28/07/18)

- ↑ William E. Melchione, M. Scott Sullivan. Reliability of Measurements Obtained by Use of an Instrument Designed to Indirectly Measure Iliotibial Band Length. J Orthopedic Sports Physician Therapy 1993;18(3):511-515.

- ↑ Razib Khaund, Sharon H. Flynn, Iliotibial Band Syndrome: A Common Source of Knee Pain, American Family Physician, 2005 Apr 15;71(8):1545-1550