Vaginismus

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Vaginismus is a sexual pain disorder that is characterized by difficulties and pain with vaginal insertion (e.g. during sexual intercourse, or when using a tampon) as well as significant fear and anxiety associated with penetration.[1][2] [3] This results in the avoidance of sexual intercourse, vaginal exams and tampon use and causes significant distress and reduced quality of life for the individual experiencing it.[1][2][4][5][6]

It has traditionally been referred to as an involuntary contraction or hypertonic state of the pelvic floor muscles (PFMs) due to actual or anticipated pain associated with vaginal penetration, causing women to feel pain, fear and anxiety with penetration attempts.[1][7] However, a strong psychological component is associated with its presentation and it has therefore been described as a psychosexual dysfunction.[2] Awareness of this psychological pain driver is paramount to the management of this condition.

According to DSM-V classification Vaginismus has been classified under "Genito-pelvic pain/Penetration disorder".[8]

The quality of evidence regarding vaginismus is low as very few Randomized Controlled trials (RCT) are done. Therefore its aetiology, pathology and treatments lack good quality literature.

Anatomy[edit | edit source]

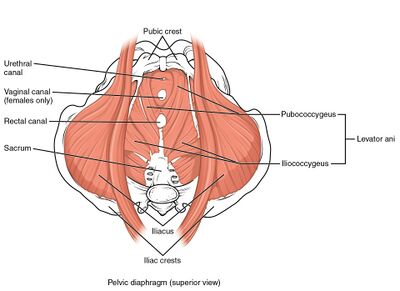

Muscles hypothesised to be involved:[9]

- Levator ani

- Puborectalis (with deep external anal sphincter)

- Bulbocavernosus muscle (with external anal sphincter)

Prevalence and Incidence[edit | edit source]

It is difficult to determine the prevalence of vaginismus due to the stigma and embarrassment experienced by people with sexual disorders which results in reduced help-seeking behaviour in individuals with this condition.[3][10] Therefore, those studies that report a prevalence (e.g. 1-6% in the general population[11]) likely underestimate the true prevalence of the condition in the population.[3][10] Estimates of prevalence may be more accurate in more specialised settings e.g. 30% in primary care settings [12] and 42% in specialized clinics for female sexual disorders.[13][14]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Several psychosocial and organic factors have been proposed to be associated with the development of vaginismus but further research is needed to support these associations. These factors are thought to contribute to the anxiety, fear, muscle hypertonicity/spasm and pain associated with vaginismus.

Organic Pathologies[2][15][edit | edit source]

- Hymen/congenital abnormalities

- Local infections

- Trauma associated with childbirth

- Genital injury/surgery or radiotherapy

- Vaginal lesions and tumours

- Vestibulodynia

- Vaginal atrophy

- Pelvic congestion

- Endometriosis

- Irritation of the vagina

Psychosocial Factors [2] [3] [16][edit | edit source]

- Psychological/physical/sexual trauma or abuse

- Strict sexual/religious upbringing

- Negative family messaging and personal views around sexuality

- Facing difficulties in a relationship.

- Fear of first-time sex (pain, bleeding, tearing, ripping, penis too large, vagina too small, sexually transmitted diseases, fear of pregnancy)

- Fear of gynaecological examinations

- A maternal influence involving grandmothers, mothers, twins, and sisters. The influence is due to merely hearing about the difficulties faced by them and the patient may manifest it as a subsequent fear of penetration.

Quality Of Life[edit | edit source]

This condition influences the quality of life. In the most serious form, it can result in an unconsummated marriage, and sterility and thus further result in the couple leading a separate life.[7] It is correlated with poor sexual quality of life[6] and even the male partners may have important effects on the development, maintenance and exacerbation of vaginismus (in lifelong vaginismus (LLV)).[17] Common psychological symptoms seen are depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, insecure attachment styles, histrionic/hysterical traits and an inability to describe own emotions.[15]

Pathophysiology/Mechanism[edit | edit source]

There is a theory that this condition is caused by a disorder of the sacral reflex arc conducting the stimulus but further research is needed in this area.[9]

Classifications[1][16][edit | edit source]

| Classification | Features |

|---|---|

| Total vaginismus | Unable to tolerate vaginal penetration |

| Partial Vaginismus | Able to tolerate penetration but with significant pain and difficulty |

| Primary/Lifelong vaginismus | Present from the first attempt at penetration; has never had pain-free intercourse.[18][19]Often the aetiology is of idiopathic origin. |

| Secondary Vaginismus | Vaginismus occurs after sexual intercourse was previously normal/pain-free. It is seen following physical or psychological trauma, infection, menopausal changes or other pelvic pathologies. The patient is no longer able to be penetrated because of the involuntary muscle spasms. It may be situational and is often associated with dyspareunia.[18][19] |

| Situational Vaginismus | Occurs only under specific circumstances: with a certain partner, or with a specific form of penetration ( e.g the individual can tolerate tampon use/finger penetration but not intercourse) |

| Global vaginismus | Occurs all the time independent of the situation |

| Spasmodic Vaginismus | Due to spasms of the pelvic floor |

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

- History of severe pain during intercourse and/or intercourse is impossible[16]

- Pelvic floor dysfunction: Spasm or increased muscle tone[3][20]

- The individual is unable to tolerate gynecological examinations[16]

- The individual has fear and anxiety associated with vaginal penetration[3][20] [21]

- The individual displays behavioral avoidance of vaginal penetration[3]

- The individual may demonstrate negative beliefs and attitudes towards sexual functioning[3]

- Inability to use a tampon (often seen at a young age)

Assessment[edit | edit source]

History[edit | edit source]

A thorough medical and psycho-sexual history needs to be taken. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) or alternatively Vaginal Penetration Cognition Questionnaire (VPCQ) can be used. Clarify the patient's history of penetration, pain rating and anxiety rating. Pain and anxiety can be scored by the patient for tampons, cotton-tipped applicators, fingers, gynaecological examinations, dilators, and intercourse.

It is important to rule out other causes of sexual pain such as herpes virus or lichens sclerosis. Vulvodynia, vestibulodynia and dyspareunia should be considered as differential diagnoses.[16] It can be difficult to differentiate vaginismus from dyspareunia. However, the level of fear, distress, avoidance of sexual intercourse and muscle tension is much higher in those with vaginismus.[2] [3]

The following topics are important to include in the subjective history:[1]

- Is vaginal penetration possible (either during sexual intercourse, with a tampon or with fingers)?

- Is vaginal penetration painful?

- Is the patient sexually active?

- Level of anxiety associated with vaginal penetration

- Patients’ goals

- Is there a history of sexual or physical trauma?

- Are they comfortable with an internal examination? If yes, are they anxious or fearful about the internal examination?

Examination[edit | edit source]

If the patient is willing and comfortable to move forward with an internal pelvic exam, the clinician should assess the level of muscle tone and trigger points within the pelvic floor musculature as well as the general functioning of these muscles. The Lamont grading system can be utilized to diagnose the severity of vaginismus .[4] [5] [16] [22] This scale is based on the patient's response to the internal pelvic exam (The Lamont Scale - What Is It?, 2016; Figure 1. The Lamont Scale. Descriptions of Lamont Grades 1À4., n.d.).[4][5][16][22]

In 1978 Lamont[22] described the first four grades and a grade 5 was later added by Pacik[16]. The Lamont grades were based on the patient's conduct during gynaecological examination and history taking whereas the Pacik grade 5 takes into account the severe fear and anxiety seen in the patient while performing the examination.

| GRADES | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Lamont grade 1 | Pelvic floor spasm but the patient can relax to allow for the exam |

| Lamont grade 2 | Pelvic floor spasm without the ability to relax |

| Lamont grade 3 | Pelvic floor spasm is strong and the patient lifts their buttocks off the exam table to retreat from the examination |

| Lamont grade 4 | Generalized retreat: Buttocks lift, thighs close, the patient fully retreats from the examination table and does not allow for examination |

| Pacik grade 5 | Generalized retreat as in level 4 plus visceral reaction, which may result in any one or more of the following: palpitations, hyperventilation, sweating, severe trembling, uncontrollable shaking, screaming, hysteria, wanting to jump off the table, a feeling of becoming unconscious, nausea, vomiting, and even a desire to attack the doctor |

Checking the Degree of vaginal muscle hypertonus/spasm[16]

| Degree of spasm | Description |

|---|---|

| 1-2 | Minimal/mild degrees of vaginal hypertonus/spasm |

| 3 | Considerable vaginal hypertonus/spasm. Finger

penetration possible, but vaginal musculature is tight. The patient is uncomfortable with the examination. |

| 4 | Presence of vaginal muscle spasm. Bulbocavernosus

seems like a tightly closed fist and digital penetration is difficult to impossible without sedation. |

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis is based on the history and symptoms of the patient. Documenting the amount of pain and anxiety with various forms of vaginal penetration is helpful in understanding a patient's perception of penetration pain. The diagnosis of vaginismus is made by a history of severe pain during intercourse or intercourse being impossible which feels like "hitting a brick wall" or "there is no hole down there" is indicative of vaginal spasm of the opening of the vagina and is often diagnostic of severe vaginismus, which is an important differentiation from dyspareunia, vulvodynia and vestibulodynia.[16] This history and the inability to tolerate gynaecological examinations are two important diagnostic features of severe vaginismus.[16]

Patients with vaginismus may have an aversion to pelvic touch related to the fear of pain and behavioural avoidance and may not permit pelvic examination, cotton-tipped testing, and EMG evaluation.[16]

Patients who score themselves as "10's" (severe pain and severe anxiety) with all forms of penetration have much more difficulty incorporating the suggestion of therapy.[16]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

As per evidence, the unwillingness or inability to experience/attempt vaginal penetration has been recommended to differentiate vaginismus from dyspareunia and provoked vestibulodynia.[23] Extreme fear and anxiety towards penetration of any object in the vagina is a crucial diagnostic factor.

The conditions which can be differentially diagnosed from vaginismus are;

- Dyspareunia- genital pain that is experienced before, during and after having coitus.

- Vulvodynia- chronic and anonymous pain that is felt around the introitus of the vagina.

- Vestibulodynia- unexplained pain around the opening of the vagina and inner lips of the vulva aka the vestibule.

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Patients who are able to tolerate some forms of penetration and who have lower pain and anxiety scores tend to be easier to treat in that they are able to cooperate with the proposed treatment. Hence their prognosis is also better when compared to other higher grades of vaginismus.

Management[edit | edit source]

The management of vaginismus needs to be multimodal to address the physical, emotional and psychological contributors to its presentation and should ideally include a multidisciplinary team consisting of a gynaecologist, physiotherapist and a psychologist/sex therapist.[20]

Non-Surgical Management[edit | edit source]

Therapy/Counseling[edit | edit source]

Psychotherapy for vaginismus aims to address the anxiety, depression, fear avoidance and relational stressors associated with the conditions.[16]Options include;[2][16]

- Marital

- Interactional

- Existential–experiential

- Relationship enhancement

- Sex counselling

- Hypnotherapy

These therapies are usually based on the assumption that vaginismus is a consequence of marital problems, negative sexual experiences in childhood or a lack of sexual education.

The therapy can be conducted in an individual or couple format. In individual therapy, the treatment is to identify and resolve underlying psychological problems that could be causing the disorder. In couples therapy, the disorder is designed as a problem for the couple and the treatment inclines to aim at the couple’s sexual history and any other problems that may be occurring in the relationship.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy[edit | edit source]

There are two methods used for CBT;

- Vaginismus could be treated with behaviorally-oriented sex therapy that includes vaginal dilatation as described by Masters and Johnson’s.[24] In the first step of the treatment there is a physical demonstration of the vaginal muscle spasm to the patient (and the partner) during a gynaecological examination. The couple is then directed to insert a series of dilators of graduated sizes at home guided by both the patient and her partner with the aim of desensitizing the patient to vaginal penetration. This treatment regimen also emphasized the importance of education regarding sexual function and the development and maintenance of vaginismus in order to relieve the psychological impact of the disorder.[2]

- Van Lankveld’s group reformulated their conceptualization of vaginismus from a sexual disorder to a vaginal penetration phobia.[25] Their treatment for vaginismus focused more explicitly and systematically on the fear of coitus through the use of prolonged, therapist-aided exposure therapy. The treatment was comprised of education on the fear and avoidance model of vaginal penetration as well as of a maximum of three two-hour sessions of in vivo exposure to the stimuli feared during vaginal penetration. This exposure treatment is said to be successful in decreasing fear and negative penetration beliefs.[2]

Pharmacological Therapy[edit | edit source]

There are three main types of pharmacological treatment for vaginismus;

- Local Anaesthetics (e.g. lidocaine gel) - based on the rationale that muscle spasms in vaginismus are due to repeated pain experienced with vaginal penetration and thus the use of a topical anaesthetic will lead to a reduction in the pain and associated spasm.[2]

- Muscle Relaxants (e.g. nitroglycerin ointment and botulinum toxin) A topical nitroglycerin ointment is used to treat the muscle spasm by relaxing the vaginal muscles.[2] Botulinum toxin, a temporary muscle paralytic, has been recommended in the treatment of vaginismus with the aim of decreasing the hypertonicity of the pelvic floor muscles.[16] The patient who receives an injection of botulinum toxin is able to engage in ‘satisfactory intercourse'.[2]

- Anxiolytic Medication (e.g. diazepam) - based on the rationale that vaginismus is a psychosomatic condition resulting from past trauma and therefore anxiety-reducing medication will resolve the symptoms. Used in conjunction with psychotherapy.[2]

Pelvic Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

A pelvic floor physiotherapist can help to restore function by treating altered PFM tone, improving PFM functioning, and reducing the pain and anxiety associated with penetration.[2]

- Breathing/relaxation[2]

- Tissue desensitization with graded vaginal dilators[2]

- Pelvic floor exercises +/- biofeedback[1] [2]

- Manual therapy[2]

- Electrotherapeutic Currents

Treatment Protocol [26]

- Counsel the patient- Educate the patient about the anatomy and physiology of the vulva, vagina, and pelvic floor muscles with the help of diagrams, pictures, and models. Explain the protective role of voluntary muscle contraction as a response to pain or expected pain and emphasize the fact that the pain does not automatically imply that there is tissue damage but is rather helping to communicate to us the threat or perceived danger. Explain the whole treatment procedure. Reassure the patient that the treatment can be discontinued whenever they want, the therapist would not treat when they are anxious or fearful, the treatment will progress at the patient's pace. Encourage the patient to invite their partner(if has one) to attend any or all of the treatment sessions and to involve the partner in-home exercises protocol whenever possible.

- Ask the patient to lie in a supine position with knees bent and feet flat on the bed; head elevated on pillows so constant eye contact could be kept between the therapist (positioned at the foot of the treatment bed) and the patient. If the patient felt any pain or anxiety they need to articulate this by saying, “Stop.” The word “Stop” would indicate to the therapist to stop the movement or technique and stay still until the pain or anxiety is reduced or ceased. Until the pain ceases take this opportunity to discuss the role of the nervous system and neuroplasticity in the treatment of vaginismus.

- Progression of the treatment session a. Being able to tolerate perineal pressure with the palm of the therapist’s hand. b. Looking at genitalia with a mirror. c. Tolerating the therapist resting one finger on the introitus. d. Tolerating the insertion of the finger into the vagina. e. Tolerating movement of the finger inside the vagina.

- This progression enables the usage of manual techniques to enhance proprioception and voluntary control of the pelvic floor muscles; techniques included stretches, myofascial and trigger point releases, and massage.

- Kegel exercises are to be given with resistance only and with a focus on relaxation rather than contraction. This implies that the patient can now carry out contract/relax exercises with a dilator vaginally inserted to assist in proprioception.

- Two finger insertion to inserting a tampon then to a series of three graduated dilators, at last, a speculum is used in a gradual manner to increase the patient's confidence.

- Teach the patient how to relax (“drop”) her pelvic floor muscles, ask them to practice this during the day if the patient feels that the muscles are tense, and then focus on dropping the pelvic floor during any insertion technique.

- Electromyographic biofeedback with a vaginal sensor should be used as a teaching tool whenever the therapist feels it's appropriate. With this technique, the patient can see the effect of contraction and relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles in a form of a graph whilst showing electrical muscle activity on the computer screen and thereby learning to recognize the sensation of a relaxed pelvic floor while receiving feedback from the electromyographic display.

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, a low-intensity, biphasic electrical current delivered by a vaginal sensor, can be used to reduce pain through nociceptive inhibition in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord.

- Treatment techniques (e.g., stretches, dilator insertion) are assigned for home practice, either done by the patient alone or with her partner. Home exercises involve the patient inserting a finger, thumb, or dilator into the vagina, which is progressed to the movement of fingers, then to massaging of the vaginal walls and stretching of the opening of the vagina at 4, 6, and 8 o’clock. The therapist should also suggest relaxation and breathing exercises at home. Massaging the vaginal walls gives the patient a chance to palpate the muscular tension and to experience what contraction and relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles feel like, thereby improving proprioceptive awareness.[26] If the massage is done by the therapist -it is done in lithotomy position under infrared light to increase blood flow.[27]Sensation focus technique can be done by the partner at home, where the partner massages the entire body except breast and genital areas without penetration which causes the patient to feel relaxed and calm.[27]

- Each step mentioned above should be practised until there is no pain or anxiety before moving on to the next step. Once the patient can tolerate insertion and movement of the larger dilator, preferably by her partner, the transition to intercourse should be encouraged. Also, motivate the patient the use stops as needed and focus on keeping the pelvic floor muscles relaxed at all times.

The use of interferential current for the treatment of vaginismus is still under trial.[28]

Surgical Management[edit | edit source]

Removal of hymenal remnants-Hymenectomy.[16]

Combination Treatment of Sacral Erector Spinae Plane Block and Progressive Dilatation is under trial.[29]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Crowley, T., Goldmeier, D., & Hiller, J. (2009). Diagnosing and managing vaginismus. BMJ, 338, b2284. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2284

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 Lahaie MA, Boyer SC, Amsel R, Khalifé S, Binik YM. Vaginismus: a review of the literature on the classification/diagnosis, etiology and treatment. Women’s Health. 2010 Sep;6(5):705-19.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 McEvoy, M., McElvaney, R., & Glover, R. (2021). Understanding vaginismus: A biopsychosocial perspective. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 0(0), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2021.2007233

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Anğın, A. D., Gün, İ., Sakin, Ö., Çıkman, M. S., Eserdağ, S., & Anğın, P. (2020a). Effects of predisposing factors on the success and treatment period in vaginismus. JBRA Assisted Reproduction, 24(2), 180–188. https://doi.org/10.5935/1518-0557.20200018

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Anğın, A. D., Gün, İ., Sakin, Ö., Çıkman, M. S., Eserdağ, S., & Anğın, P. (2020b). Effects of predisposing factors on the success and treatment period in vaginismus. JBRA Assisted Reproduction, 24(2), 180–188. https://doi.org/10.5935/1518-0557.20200018

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Psychological predictors of sexual quality of life among women with vaginismus, Velayati A, Jahanian Sadatmahalleh S, Ziaei S, Kazemnejad A. Psychological predictors of sexual quality of life among Iranian women with vaginismus: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2022 Jan 2;34(1):81-9.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Laskowska A, Gronowski P. Vaginismus: An overview. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2022 May 1;19(5):S228-9.

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association DS, American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American psychiatric association; 2013 May.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Shafik A, El-Sibai O. Study of the pelvic floor muscles in vaginismus: a concept of pathogenesis. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2002 Oct 10;105(1):67-70.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Shifren, J. L., Johannes, C. B., Monz, B. U., Russo, P. A., Bennett, L., & Rosen, R. (2009). Help-Seeking Behavior of Women with Self-Reported Distressing Sexual Problems. Journal of Women’s Health, 18(4), 461–468. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2008.1133

- ↑ Konkan, R., Bayrak, M., Gönüllü, O. G., Şenormanci, Ö., & Sungur, M. Z. (2012). Vajinusmuslu Kadınlarda Cinsel İşlev Ve Doyum / Sexual Function And Satisfaction of Women With Vaginismus. Dusunen Adam: The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences. https://doi.org/10.5350/DAJPN2012250402

- ↑ Read S, King M, Watson J. Sexual dysfunction in primary medical care: prevalence, characteristics and detection by the general practitioner. Journal of Public Health. 1997 Dec 1;19(4):387-91.

- ↑ Oniz A, Keskinoglu P, Bezircioglu I. The prevalence and causes of sexual problems among premenopausal Turkish women. The journal of sexual medicine. 2007 Nov 1;4(6):1575-81.

- ↑ Nusbaum MR, Gamble G, Skinner B, Heiman J. The high prevalence of sexual concerns among women seeking routine gynaecological care. Journal of Family practice. 2000 Mar 1;49(3):229-.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Maseroli E, Scavello I, Rastrelli G, Limoncin E, Cipriani S, Corona G, Fambrini M, Magini A, Jannini EA, Maggi M, Vignozzi L. Outcome of medical and psychosexual interventions for vaginismus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The journal of sexual medicine. 2018 Dec 1;15(12):1752-64.

- ↑ 16.00 16.01 16.02 16.03 16.04 16.05 16.06 16.07 16.08 16.09 16.10 16.11 16.12 16.13 16.14 16.15 16.16 16.17 16.18 16.19 Pacik PT. Understanding and treating vaginismus: a multimodal approach. International urogynecology journal. 2014 Dec;25(12):1613-20.

- ↑ Turan Ş, Sağlam NG, Bakay H, Gökler ME. Levels of depression and anxiety, sexual functions, and affective temperaments in women with lifelong vaginismus and their male partners. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2020 Dec 1;17(12):2434-45.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Jeng CJ, Wang LR, Chou CS, Shen J, Tzeng CR. Management and outcome of primary vaginismus. Journal of sex & marital therapy. 2006 Dec 1;32(5):379-87.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 McGuire H, Hawton KK. Interventions for vaginismus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2001(2).

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 Melnik, T., Hawton, K., & McGuire, H. (2012). Interventions for vaginismus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001760.pub2

- ↑ Watts, G., & Nettle, D. (2010). The Role of Anxiety in Vaginismus: A Case-Control Study. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(1, Part 1), 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01365.x

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 The Lamont Scale—What is it? (2016, July 20). The ObG Project. https://www.obgproject.com/2016/07/20/lamont-scale/

- ↑ Lahaie MA, Amsel R, Khalifé S, Boyer S, Faaborg-Andersen M, Binik YM. Can fear, pain, and muscle tension discriminate vaginismus from dyspareunia/provoked vestibulodynia? Implications for the new DSM-5 diagnosis of genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder. Archives of sexual behavior. 2015 Aug;44(6):1537-50.

- ↑ Masters WH, Johnson VE: Human Sexual Inadequacy. Little, Brown, Boston, USA (1970).

- ↑ Van Lankveld JJ, ter Kuile MM, de Groot HE, Melles R, Nefs J, Zandbergen M. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for women with lifelong vaginismus: a randomized waiting-list controlled trial of efficacy. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2006 Feb;74(1):168.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Reissing ED, Armstrong HL, Allen C. Pelvic floor physical therapy for lifelong vaginismus: a retrospective chart review and interview study. Journal of sex & marital therapy. 2013 Jul 1;39(4):306-20.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 World Health Organisation. International clinical trials registry platform. Available from: https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=IRCT2016061828486N1 (accessed 27/06/2022)

- ↑ de Abreu Pereira CM, Ambrosio RT, Borges EM, Lima SM, dos Santos Alves VL. Physiotherapy protocol with the interferential current in the treatment of vaginismus-Observational and prospective study. Manual Therapy, Posturology & Rehabilitation Journal. 2019 May 27:1-5.

- ↑ Yilmaz EP, Ahiskalioglu EO, Ahiskalioglu A, Tulgar S, Aydin ME, Kumtepe Y. A novel multimodal treatment method and pilot feasibility study for vaginismus: Initial experience with the combination of sacral erector spinae plane block and progressive dilatation. Cureus. 2020 Oct 8;12(10).