Understanding Red Flags in Patellofemoral Pain

Top Contributors - Carin Hunter, Jess Bell and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Screening for red flags is an important part of the assessment process, but it is often overlooked in patients with knee pain. It is important to have a good understanding of red flags for patient safety and to ensure appropriate and timely referrals are made when necessary. If there has been any trauma to the knee, it is necessary to make sure that all relevant investigations have been carried out. For more information on red flags, please see this page: An Introduction to Red Flags in Serious Pathology.

Non-Traumatic Masquerading Conditions[edit | edit source]

There are certain conditions that can have similar pain patterns as patellofemoral pain, and these should be considered in a differential diagnosis. The following non-traumatic conditions occur in the adolescent population (i.e. pre-teen and teen).[1]

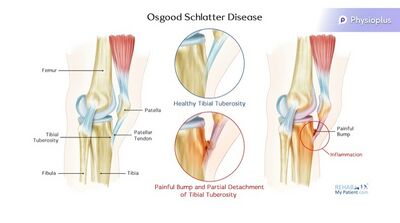

Osgood-Schlatter Disease (OSD)[edit | edit source]

Signs and Symptoms:

- This condition is common in adolescents aged 11-15 years old[2]

- It is prevalent in children participating in quadriceps dominant sports, i.e. running, kicking and jumping[2]

- Patients present with an obvious bump at the tibial tubercle[3]

- Pain is specific to the tibial tubercle

- Inflammation and elevation of the growth plates are present in the tibial tuberosity

- An MRI to show the level of inflammation can be used as confirmation, but this will not change the treatment plan

- Pain can progress to a level that prevents any participation in sport if left untreated

Treatment:

- Education

- Activity modification:[1][2][3]

- Try to eliminate the patient's least favourite sport, or

- Change their playing position to a less active position to decrease load

- NSAIDS (non-steroidal anti-inflammatories)

- Ice massage - this will provide symptomatic relief

- Address overload:

For more information, please see Osgood-Schlatter Disease.

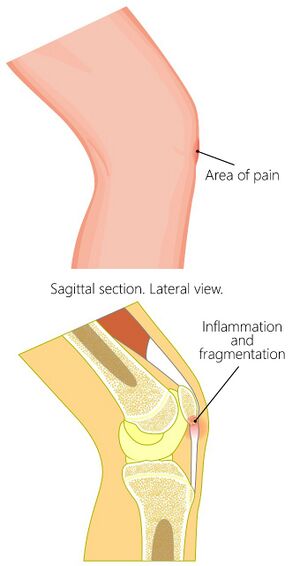

Sinding Larsen Johansson Syndrome[edit | edit source]

Sinding Larsen Johansson Syndrome (SLJS) is a juvenile osteochondrosis and traction epiphysitis. It affects the extensor mechanism of the knee, which disturbs the patella tendon attachment to the inferior pole of the patella. There is tenderness of the inferior pole of the patella. This is usually accompanied by x-ray evidence of splintering of that pole. Most patients with SLJS also have calcification at the inferior pole of the patella.[6]

The syndrome usually appears in adolescence, during a growth spurt. It is associated with localised pain which is worsened by exercise. Usually localised tenderness and soft tissue swelling are observed. The surrounding muscles may also be tight, particularly the quadriceps, hamstrings and gastrocnemius. This tightness usually results in inflexibility at the knee joint, which alters the stress applied through the patellofemoral joint.[7]

Signs and Symptoms:

- Inflammation at the growth plate of the distal pole of the patella[8]

- This condition is most likely to be seen during growth spurts

- Primary treatment focuses on tracking growth for activity modification during a growth spurt[9]

- Pain can progress to a level that prevents any participation in sport

Treatment:

- Education

- Activity modification:[1]

- Try to eliminate the patient's least favourite sport, or

- Change their playing position to a less active position to decrease load

- NSAIDS (non-steroidal anti-inflammatories)

- Ice massage - to provide symptomatic relief

- Address overload:

- Extrinsic factors

- Load management of sport

- Footwear

- Landing technique

- Intrinsic factors

- Muscle length

- Muscle strength

- Extrinsic factors

For more information, please see Sinding-Larsen-Johansson Syndrome.

Knee Effusion[edit | edit source]

There are no instances where a child should have a knee effusion without a cause. Thus, any effusion in the absence of trauma should always be investigated. A knee effusion can often lead to patellofemoral pain.

Possible Effusion Causes:

- Systemic autoimmune disease (eg. juvenile arthritis)

- Infective arthritis

- Osteochondritis dissecans

Autoimmune Disease Red Flags:

- Multiple joint involvement

- Joint is stiff on waking

- Fatigue

Infective Arthritis Red Flags:

- Temperature

- Recent illness

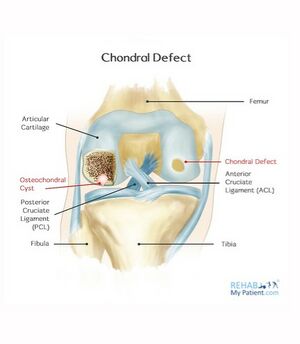

Osteochondritis Dissecans/Osteochondral Defect[edit | edit source]

Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) is defined as an inflammatory pathology of bone and cartilage. This can result in localised necrosis and fragmentation of bone and cartilage.[10] Cartilage and subchondral bone can break off and float in the joint. This irritates the synovium, which causes an effusion.

Osteochondritis Dissecans Treatment:

- Manage conservatively for stable lesions[11]

- Possible debridement / knee wash out

- Possible surgical resection (resect back to a stable margin)

- Review the osteochondral defects with an MRI[12] - check for stability of the margins of the osteochondral defect and if the location is a weight-bearing zone

- Monitor bone oedema around a defect - the oedema should decrease when serially monitored

- Physiotherapy advice: load management

- When there is a trochlear osteochondral defect in the patellofemoral joint, remember to avoid excessive deep loaded flexion

For more information, please see Osteochondritis Dissecans and Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee.

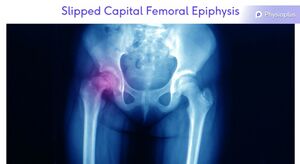

Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis[edit | edit source]

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis is not common. However, it needs to be considered as a differential diagnosis[13] as it is can refer pain to the anteromedial knee. A mild condition diagnosed early has a better outcome as the condition will progress until the epiphysis is fused.[13]

For more information, please see Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis.

Others[edit | edit source]

Less common but more serious:

- Systemic auto-immune disease

- Slipped epiphysis

- Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI)

- Leukaemia

- Metastatic neuroblastoma

- Primary bone tumour

- Red flags

- Night pain

- Weight loss

- Malaise

Conditions That Can Occur in the Adult Population[edit | edit source]

The following conditions should be considered in the differential diagnosis of adults presenting with patellofemoral pain symptoms.

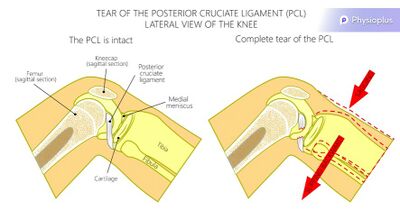

Posterior Cruciate Ligament Rupture[edit | edit source]

A rupture of the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) can be caused by a blow to the front of the knee.[14] For some patients, their only reported symptom is patellofemoral joint pain. It is, therefore, advisable to assess all ligaments to see if surgery is necessary.[14] Physiotherapy for an injury to the PCL will often focus on quadriceps rehabilitation.

For more information, please see this page: PCL Reconstruction.

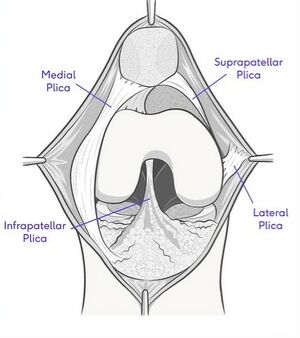

Synovial Plica[edit | edit source]

A plica is a fold in the synovial membrane. They are common and are normally asymptomatic. A plica can often be palpated anteromedially, next to the superior half of the patella. Occasionally, they can get trapped in the patellofemoral joint, and become impinged or inflamed and sore.[15]

Diagnosis:

- Inject with local anaesthetic for symptomatic relief. If this is successful, it strongly indicates an inflamed synovial plica.

Treatment:

- Steroid injections to decrease inflammation

- Plica resection

- Rehabilitation[15]

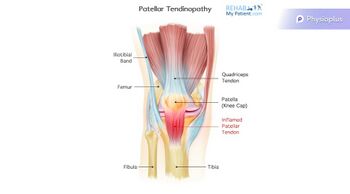

Patellar Tendinopathy[edit | edit source]

Tendinopathy is a failed healing response of the tendon, with haphazard proliferation of tenocytes, intracellular abnormalities in tenocytes, disruption of collagen fibres, and a subsequent increase in non-collagenous matrix.[16][17][18] The term tendinopathy is a generic descriptor of the clinical conditions (both pain and pathological characteristics) associated with overuse in and around tendons.[19]

Treatment:

- Heavy resistance loading

- Eccentric[20] decline loading

| Patellar Tendinopathy | Patellofemoral Pain | |

|---|---|---|

| Aggravating Factors | Being still[21]

Early morning |

Being still if knee at end of range flexion |

| Description of Pain | Pinpoint to proximal tendon[21] | Vague |

| Effect of Excercise | Pain decreases as tendon warms up[21] | Worsens with repetitive load |

For more information, please see Patellar Tendinopathy.

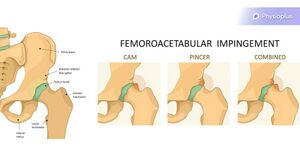

Femoroacetabular Impingement[edit | edit source]

While femeroacetabular impingement (FAI) is not common, it can refer pain to the anteromedial knee. This referred pain could be confused with patellofemoral pain. One of the most commonly recognised clinical signs for FAI is pain with hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation,[22] so it can be useful to perform the Quadrant Test. In relation to patellofemoral pain, you will be looking to see if the patient's knee pain is reproduced on testing.

For more information, please see Femoroacetabular Impingement.

Assessment Tools[edit | edit source]

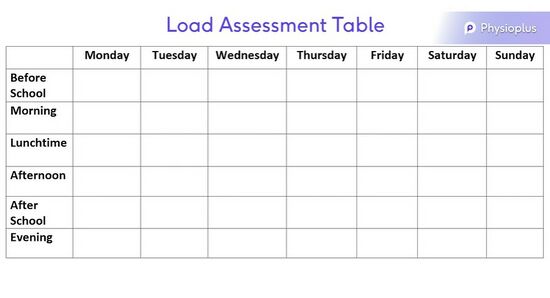

When encouraging an individual to modify their activity levels, it can be helpful to print out / provide a table for them to accurately track their volume of exercise in a week (see figure below). Be sure to encourage your client to fill out the form accurately as this will ensure you can offer the most relevant advice. It is also advisable to correctly record the length of time spent on each activity and the intensity of the activity.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Robertson C. Understanding Red Flags in Patellofemoral Pain Course. Plus. 2022.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Neuhaus C, Appenzeller-Herzog C, Faude O. A systematic review on conservative treatment options for OSGOOD-Schlatter disease. Physical Therapy in Sport. 2021 May 1;49:178-87.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Corbi F, Matas S, Álvarez-Herms J, Sitko S, Baiget E, Reverter-Masia J, López-Laval I. Osgood-Schlatter Disease: Appearance, Diagnosis and Treatment: A Narrative Review. InHealthcare 2022 May 30 (Vol. 10, No. 6, p. 1011). MDPI.

- ↑ O’Sullivan IC, Crossley KM, Kamper SJ, van Middelkoop M, Vicenzino B, Franettovich Smith MM, Menz HB, Smith AJ, Tucker K, O’Leary KT, Costa N. HAPPi Kneecaps! A double-blind, randomised, parallel group superiority trial investigating the effects of sHoe inserts for adolescents with patellofemoral PaIn: phase II feasibility study. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research. 2021 Dec;14(1):1-1.

- ↑ Gaulrapp H, Nührenbörger C. The Osgood-Schlatter disease: A large clinical series with evaluation of risk factors, natural course, and outcomes. International Orthopaedics. 2022 Feb;46(2):197-204.

- ↑ Medlar RC, Lyne ED. Sinding-Larsen-Johansson disease. Its etiology and natural history. The Journal of Bone and Joint surgery. American Volume. 1978 Dec 1;60(8):1113-6.

- ↑ Houghton, K. M., ‘Review for the generalist: evaluation of anterior knee pain’, Paediatric Rheumatology, (2007), vol. 5, p. 4-10.

- ↑ Fischer AN. Sinding-Larsen-Johansson Syndrome. InCommon Pediatric Knee Injuries 2021 (pp. 63-68). Springer, Cham.

- ↑ McCormick KL, Tedesco LJ, Bixby EC, Swindell HW, Popkin CA, Redler LH. Sinding-Larsen-Johansson Disease: Analysis of the Associated Factors in the Largest Cohort to Date. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2022 May 31;10(5_suppl2):2325967121S00503.

- ↑ Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Elbow

- ↑ Chau MM, Klimstra MA, Wise KL, Ellermann JM, Tóth F, Carlson CS, Nelson BJ, Tompkins MA. Osteochondritis dissecans: current understanding of epidemiology, etiology, management, and outcomes. JBJS. 2021 Jun 16;103(12):1132-51.

- ↑ Detterline AJ, Goldstein JL, Rue JP, Bach BR. Evaluation and treatment of osteochondritis dissecans lesions of the knee. Journal of Knee Surgery. 2008;21(02):106-15.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Purcell M, Reeves R, Mayfield M. Examining delays in diagnosis for slipped capital femoral epiphysis from a health disparities perspective. Plos one. 2022 Jun 24;17(6):e0269745.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Perelli S, Masferrer-Pino Á, Morales-Ávalos R, Fernández DB, Ruiz AE, Gallego JT, Idiart R, Fabregat ÁA, Alcaraz10 NU. Current management of posterior cruciate ligament rupture. A narrative review. Rev Esp Artrosc Cir Articul. 2021;28(3):180-91.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Casadei K, Kiel J. Plica syndrome. StatPearls [Internet]. 2021 Jul 25.

- ↑ Maffulli N, Longo UG, Franceschi F, Rabitti C, Denaro V. Movin and Bonar scores assess the same characteristics of tendon histology. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2008 Jul;466(7):1605-11.

- ↑ Maffulli N, Longo UG, Maffulli GD, Rabitti C, Khanna A, Denaro V. Marked pathological changes proximal and distal to the site of rupture in acute Achilles tendon ruptures. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2011 Apr;19(4):680-7.

- ↑ Alexander L, Shim J, Harrison I, Moss R, Greig L, Pavlova A, Parkinson E, Maclean C, Morrissey D, Swinton P, Brandie D. Exercise therapy for tendinopathy: a scoping review mapping interventions and outcomes.

- ↑ Maffulli N. Overuse tendon conditions: time to change a confusing terminology. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 1998 Nov 1;14(8):840-3.

- ↑ Challoumas D, Pedret C, Biddle M, Ng NY, Kirwan P, Cooper B, Nicholas P, Wilson S, Clifford C, Millar NL. Management of patellar tendinopathy: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised studies. BMJ open sport & exercise medicine. 2021 Nov 1;7(4):e001110.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Rosen AB, Wellsandt E, Nicola M, Tao MA. Current clinical concepts: clinical management of patellar tendinopathy. Journal of Athletic Training. 2021 Oct 1.

- ↑ Hale RF, Melugin HP, Zhou J, LaPrade MD, Bernard C, Leland D, Levy BA, Krych AJ. Incidence of femoroacetabular impingement and surgical management trends over time. The American journal of sports medicine. 2021 Jan;49(1):35-41.