Creatine and Exercise

Original Editors - Stephen Sheffield, James Williams, Katherine Metz,Jessica Hobbs, Maddisen Coleman, Marilyn Kozlowski, Cara Stowers, Kaylee Johnson, Lauren Hebensperger, Samantha McGraw, Emily North, Kyle Covey, Landon Andrews, Kylie Volk, Matthew Wolfe as part of the University of Oklahoma Exercise Science Project

Top Contributors - Marilyn Kozlowski, James Williams, Safiya Naz, Stephen Sheffield, Kylie Volk, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Lauren Hebensperger, Laura Ritchie, Landon Andrews, Emily North, Maddisen Coleman, Cara Stowers, Kaylee Johnson, Eugene DeLoach, Katherine Metz, Lauren Lopez, Chelsea Miller, Kyle Covey, Ryan Lester, Nicole Owens, Wanda van Niekerk, Jessica Hobbs, 127.0.0.1, Evan Thomas, Samantha McGraw, Alan Tran, Matthew Wolfe and Taylor Ledford

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Creatine is an amino acid located mostly in your body's muscles as well as in the brain. Most people get creatine through seafood and red meat (though at levels far below those found in synthetically made creatine supplements). The body's liver, pancreas and kidneys also can make about 1 gram of creatine per day.

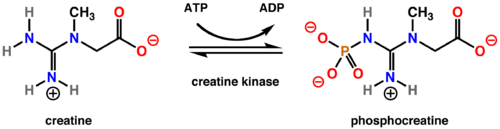

Note: Creatine kinase (CK), known previously as creatine phosphokinase or CPK, is distinct from creatinine and is a biomarker of muscle damage.

Your body stores creatine as phosphocreatine primarily in your muscles, where it's used for energy. As a result, people take creatine orally to improve athletic performance and increase muscle mass.

- Creatine might benefit athletes who need short bursts of speed or increased muscle strength, such as sprinters, weight lifters and team sport athletes.

- While taking creatine might not help all athletes, evidence suggests that it generally won't hurt if taken as directed.

- Although an older case study suggested that creatine might worsen kidney dysfunction in people with kidney disorders, creatine doesn't appear to affect kidney function in healthy people[1]

Creatine supplementation possesses documented exercise benefits, particularly related to short, high-intensity bouts.

- Evidence suggests that improvements are possible regardless of age or gender.[2]

- Positive associations with creatine supplementation include increased strength, lean body mass, and enhanced fatigue resistance.[3]

- Creatine supplementation plus resistance training translates into a larger increase in bone mineral density, muscle strength, and lean tissue mass than just resistance training alone.[4] It has been shown that higher brain creatine is associated with improved neuropsychological performance.[4]

- For older adults, the use of creatine can improve their quality of life and may reduce the disease burden on their cognitive dysfunction.[4]

Exercise Effects[edit | edit source]

- Creatine supplements can be taken to function as an ergogenic aid during exercise.

- Creatine supplementation increases the levels of phosphocreatine (PCr) in muscles, which is used by creatine kinase to regenerate Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in skeletal muscle.

- Increased levels of PCr improves exercise performance during high intensity exercise and muscular strength and endurance.

Research has evaluated the effects of polyethylene glycol (PEG) creatine supplementation taken for a 28 day period to assess its effects on anaerobic capacity. Creatine binds to PEG, which functions as a delivery system and increases the reuptake efficiency and ergogenic effects during exercise.[6]

- Supplementation with PEG-creatine resulted in improved performance in vertical power, agility, and upper-body endurance. Some of these improvements could be due to the shortened muscle relaxation time acquired from the creatine supplementation, which would assist quickly repeated muscle movements.[6]

- The supplementation also caused an increase in body mass. The improvements generated by PEG-creatine supplementation would be most beneficial for untrained individuals. Creatine can also affect post-exercise returns to homeostasis. Creatine supplementation has been found to reduce both blood pressure and heart rate recovery time after exercise.[7]

- Long term usage of supplements, after 30 days of continual use, has also been shown to reduce exercise induced muscle damage, decreasing recovery time and maximizing performance.[8]

Anaerobic Effects[edit | edit source]

Creatine loading has been evaluated for its effects on anaerobic running capacity (ARC) and body weight changes for males and females. ARC represents the theoretical distance an individual could run using only stored anaerobic energy of ATP and PCr.

- Creatine loading increases available ATP (made in mitochondria, see image) and PCr for creatine kinase reactions.

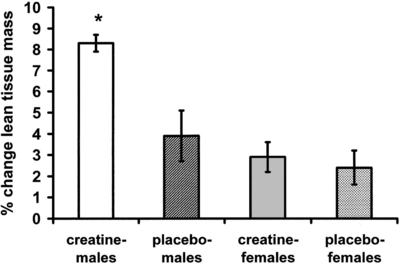

- After creatine loading, males experienced a 23% increase in ARC, but females had no significant changes.[9] This could be due to the higher resting levels of intramuscular creatine in females, which would make them less sensitive to creatine loading.

- Bodyweight changes were small in both males and females and were mostly from the increased intramuscular water volume.[9] Therefore, for sports involving running, creatine supplementation can be used to increase anaerobic running capacity in males without the potential to decrease performance from weight gain.

- Another study that supports creatine supplementation and improved anaerobic performance focused on young adult males. The participants completed two Wingate Anaerobic tests on the bicycle ergometer with average power and maximum power being measured.[10] The results of the study showed an increase in average power in those who supplemented with 20g of creatine monohydrate per day over a seven day period.[10]

Effect on Muscular Strength[edit | edit source]

Creatine's ability to improve the function of the ATP-PC system may improve muscular strength.

- One study looked at the effects of varying doses of creatine and frequency of resistance training on muscular strength over a six week period.[11] The participants performed a one-repetition max test (1RM) for upper extremity using a bench press test and one for lower extremity using a leg press test.[11] The results showed no improvement in muscular strength following creatine supplementation.[11]

- Another study examining young adult males to investigate the effects of seven days of creatine-monohydrate loading on muscular strength.[10] The study used a 1RM bench press and 1RM lower extremity test to measure changes in muscular strength.[10] The results showed no improvement in strength from creatine supplementation.[10]

- These two studies revealed insignificant results for the short-term benefits of creatine supplementation on muscular strength.

- In contrast to these studies, two studies found significant increases in muscular strength after 28-30 days of creatine supplementation with creatine monohydrate and PEG creatine supplementation.[12][6]

- A 12-week study with older adult women found increases in max strength and muscle mass.[13]

Effect on Muscular Power[edit | edit source]

The effects of creatine were studied on muscle power in elite athletes. They found that creatine can work as more of a recovery supplement, helping patients gain progress faster because they are not in the recovery stage as long. This has significant clinical implications on the effects of creatine on highly trained individuals in therapy.

Gender Differences[edit | edit source]

Like many other ergogenic aids, studies have shown that creatine supplementation will affect men and women differently.

The figure R is a chart that represents the results from a study that compared the effect creatine has on lean tissue mass in both genders.[14]

Creatine Utilization in Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

- Creatine can be effective in the rehabilitative setting. Creatine supplementation has been shown to prevent the downregulation of GLUT4 transporters, maintained muscle glycogen content, and maintained muscle creatine content during the immobilization phase of recovery.

- Creatine supplementation also helped increase muscle GLUT4, muscle glycogen, and muscle creatine levels above baseline after three weeks of rehabilitation.[15] Creatine supplementation has also been proven not only to attenuate muscle atrophy during immobilization, but to stimulate muscle hypertrophy during rehabilitative strength training.[16]

- This information is vital to the field of rehabilitation because creatine may help decrease the recovery time of patients, and increase the benefits of recovery.

- Athletes or individuals who enjoy exercising may not have to face losses in muscle strength during an injury, and their prognosis may be better after rehabilitation if they supplement with creatine during their time being injured. With these positive effects of creatine supplementation, rehabilitation professionals should consider implementing creatine supplementation into their interventions.

COPD[edit | edit source]

- Another study related to creatine use during rehabilitation is a randomized controlled trial conducted by Fuld, Kilduff, Neder, Pitsiladis, Lean, Ward, & Cotton (2005). In this study, forty-one patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) were divided into two groups.

- One group was given a creatine supplement, and the other was not. Both groups completed several different tests and went through a pulmonary rehabilitation plan. Throughout the intervention, pulmonary function, body composition, muscular strength, exercise capacity, and quality of life were evaluated. At the end of the experiment, the patients who ingested creatine showed improvements in body composition (increase in fat-free mass), muscular strength, and quality of life.

- The results are significant because they suggest patients struggling with COPD may improve peripheral strength, potentially alleviating mortality factors associated with COPD such as muscular atrophy and dysfunction.[17]

Parkinson's[edit | edit source]

- Creatine supplementation can be beneficial to patients who have Parkinson’s Disease. These individuals have decreased muscle strength, uncoordinated muscle movements, tremors and rigidity in the limbs, and loss of muscle mass.

- Several studies have been conducted to understand the effects of creatine on exercise for people who have Parkinson’s disease. The research literature concluded that creatine significantly increased muscle strength, endurance, and improved the ability to exercise in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

- Creatine supplementation can be useful for patients with Parkinson’s disease by increasing the benefits of resistance training and therapeutic exercises.[18]

Muscular Dystrophy[edit | edit source]

According to a Cochrane Systematic Review, creatine supplementation is beneficial to those diagnosed with muscular dystrophy. Several RCTs have shown short- to the intermediate-term treatment of creatine supplementation can increase a patient's muscular strength by 8.5%. Based on information collected from self-assessments, the patient's taking creatine have increased functional performance of their ADLs. Of those participating in the studies, 44% of the patients felt better while taking creatine due to their ability to function at a higher level. These patients often participate in aerobic exercise while in the clinic, but building muscle strength can help their overall daily routines. Long-term supplementation has yet to be evaluated.[19]

Creatine Utilization in the Elderly Population[edit | edit source]

- The effective use of creatine as an ergogenic aid is well documented in the research literature. However, there is less research available on its use in the elderly population.

- Exercise programs coupled with creatine supplementation results in increased strength and fat-free mass in both men and women aged over 65 years when compared with exercise alone.[20]

- Supplementing with both creatine and protein in conjunction with exercise provides greater increases in strength and fat-free mass vs. creatine supplementation alone.[21]

- Creatine appears to be a safe method of increasing strength and fat-free mass in elderly populations.

- The time frame in which creatine supplements are administered can impact the increases in muscle mass, strength, and performance of older patients.[22]

Side Effects .[edit | edit source]

A critical review of the current data concerning the safety of oral creatine supplementation illustrated many concerns of long term use.

In healthy subjects, studies of adverse effects have focused on muscle cramping, gastrointestinal symptoms, and renal/hepatic laboratory results."[23] Some other less researched effects that have been found were water retention and increased workload on the kidneys.[23]The formation of formaldehyde is commonly cited as a safety hazard associated with creatine. However, creatine supplementation does not significantly increase formaldehyde production before or after a supplementation regimen.[21]

Summary[edit | edit source]

Creatine supplementation has been shown to improve body composition, anaerobic performance, muscular strength, and muscular power, muscular endurance.[6][10][11][20][13][12][9][3] and may help to increase recovery following exercise.[24]

- The benefits of creatine supplementation are effective for both young and older adults.[22][21][20][13][4][2] Creatine may have less effect on women than men.[9]

- Creatine should be supplemented for a least 28-30 days to see improvements with longer lengths of supplementation (> 12 weeks) for more significant results.[12][6][13] Creatine loading phases lasting 5-9 days have shown inconsistent improvements in physical performance.[25][10]

In the rehabilitation setting, creatine may work as a recovery agent and shorten recovery time from injury.[15] Creatine has shown to be effective for patients with COPD, Parkinson’s disease, and muscular dystrophies.[17][18][19]

Side effects of creatine can include muscle cramping, gastrointestinal symptoms, water retention, and possible renal/hepatic changes.[23]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Mayo clinic Creatine Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements-creatine/art-20347591 (Accessed 16.3.2021)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Bemben MG, Lamont HS. Creatine supplementation and exercise performance. Sports Medicine. 2005 Feb 1;35(2):107-25.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Candow DG, Forbes SC, Little JP, Cornish SM, Pinkoski C, Chilibeck PD. Effect of nutritional interventions and resistance exercise on aging muscle mass and strength. Biogerontology. 2012;13(4):345-58.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Rawson ES, Venezia AC. Use of creatine in the elderly and evidence for effects on cognitive function in young and old. Amino acids. 2011;40(5):1349-1362.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4uJEqgsFef4

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Camic CL, Housh TJ, Zuniga JM, Traylor DA, Bergstrom HC, Schmidt RJ, Johnson GO, Housh DJ. The effects of polyethylene glycosylated creatine supplementation on anaerobic performance measures and body composition. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2014 Mar 1;28(3):825-33.

- ↑ Sanchez-Gonzalez MA, Wieder R, Kim JS, Vicil F, Figueroa A. Creatine supplementation attenuates hemodynamic and arterial stiffness responses following an acute bout of isokinetic exercise. European journal of applied physiology. 2011 Sep 1;111(9):1965-71.

- ↑ Rosene J, Matthews T, Ryan C, Belmore K, Bergsten A, Blaisdell J, Gaylord J, Love R, Marrone M, Ward K, Wilson E. Short and longer-term effects of creatine supplementation on exercise induced muscle damage. Journal of sports science & medicine. 2009 Mar;8(1):89.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Fukuda DH, Smith AE, Kendall KL, Dwyer TR, Kerksick CM, Beck TW, Cramer JT, Stout JR. The effects of creatine loading and gender on anaerobic running capacity. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2010 Jul 1;24(7):1826-33.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 Zuniga JM, Housh TJ, Camic CL, Hendrix CR, Mielke M, Johnson GO, Housh DJ, Schmidt RJ. The effects of creatine monohydrate loading on anaerobic performance and one-repetition maximum strength. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2012 Jun 1;26(6):1651-6.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Candow DG, Chilibeck PD, Burke DG, Mueller KD, Lewis JD. Effect of different frequencies of creatine supplementation on muscle size and strength in young adults. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2011 Jul 1;25(7):1831-8.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Herda TJ, Beck TW, Ryan ED, Smith AE, Walter AA, Hartman MJ, Stout JR, Cramer JT. Effects of creatine monohydrate and polyethylene glycosylated creatine supplementation on muscular strength, endurance, and power output. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2009 May 1;23(3):818-26.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Aguiar AF, Januário RS, Junior RP, Gerage AM, Pina FL, Do Nascimento MA, Padovani CR, Cyrino ES. Long-term creatine supplementation improves muscular performance during resistance training in older women. European journal of applied physiology. 2013 Apr 1;113(4):987-96.

- ↑ Chilibeck PD, STRIDE D, FARTHING JP, BURKE DG. Effect of creatine ingestion after exercise on muscle thickness in males and females. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2004 Oct 1;36(10):1781-8.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Op't Eijnde B, Ursø B, Richter EA, Greenhaff PL, Hespel P. Effect of oral creatine supplementation on human muscle GLUT4 protein content after immobilization. Diabetes. 2001 Jan 1;50(1):18-23.

- ↑ Hespel P, Op't Eijnde B, Leemputte MV, Ursø B, Greenhaff PL, Labarque V, Dymarkowski S, Hecke PV, Richter EA. Oral creatine supplementation facilitates the rehabilitation of disuse atrophy and alters the expression of muscle myogenic factors in humans. The Journal of physiology. 2001 Oct;536(2):625-33.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Fuld JP, Kilduff LP, Neder JA, Pitsiladis Y, Lean ME, Ward SA, Cotton MM. Creatine supplementation during pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2005 Jul 1;60(7):531-7..

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Hass CJ, Collins MA, Juncos JL. Resistance training with creatine monohydrate improves upper-body strength in patients with Parkinson disease: a randomized trial. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair. 2007 Mar;21(2):107-15.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Kley RA, Tarnopolsky MA, Vorgerd M. Creatine for treating muscle disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013(6).

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Brose A, Parise G, Tarnopolsky MA. Creatine supplementation enhances isometric strength and body composition improvements following strength exercise training in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2003 Jan 1;58(1):B11-9.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Candow DG, Little JP, Chilibeck PD, Abeysekara S, Zello GA, Kazachkov M, Cornish SM, Yu PH. Low-dose creatine combined with protein during resistance training in older men. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2008 Sep 1;40(9):1645-52.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Candow DG, Vogt E, Johannsmeyer S, Forbes SC, Farthing JP. Strategic creatine supplementation and resistance training in healthy older adults. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism. 2015;40(7):689-94.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Juhn MS, Tarnopolsky M. Potential side effects of oral creatine supplementation: a critical review. Clinical journal of sport medicine: official journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine. 1998 Oct 1;8(4):298-304.

- ↑ Claudino JG, Mezêncio B, Amaral S, Zanetti V, Benatti F, Roschel H, Gualano B, Amadio AC, Serrão JC. Creatine monohydrate supplementation on lower-limb muscle power in Brazilian elite soccer players. Journal of the international society of sports nutrition. 2014 Dec;11(1):1-6.

- ↑ Cramer JT, Stout JR, Culbertson JY, Egan AD. Effects of creatine supplementation and three days of resistance training on muscle strength, power output, and neuromuscular function. Journal of strength and conditioning research. 2007 Aug 1;21(3):668.