Psoriatic Arthritis

Original Editors - Stacy Downs as part of the Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Stacy Downs, Keri Gibson, Sarah Yurt, Admin, Kim Jackson, Elaine Lonnemann, Oyemi Sillo, 127.0.0.1, Wendy Walker, WikiSysop and Nikhil Benhur Abburi

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic progressive inflammatory joint disease that can be associated with psoriasis.[1] The condition may affect both peripheral joints and the axial skeleton causing pain, stiffness, swelling, and possible joint destruction. This joint pathology progresses slowly and can be more of a nuisance than disabling.[1] Psoriatic arthritis is considered a seronegative spondyloarthropathy. The fact that it is "seronegative" means that the blood tests negative for a certain factor that is present in rheumatoid arthritis. Spondyloarthropathy is a word that describes a group of conditions that all share two common characteristics. First, there is the presence of arthritis that affects the spine or extremities with evidence of family inheritance. Secondly, inflammation occurs in the ligaments, tendons, and occasionally in organs such as the eye.[2]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

- Occurs in 6%-42% of persons that have psoriasis

- Approximately 2% of the general population has psoriasis

- Psoriatic arthritis is estimated to have a prevalence of 0.1%-0.25% in the US

- Equal prevalence in both males and females [3]

- Can occur at any age but typically occurs between ages of 30-50 years old

- 80-90% chance of having psoriatic arthritis if one of your first degree relatives has the disorder[1]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Psoriatic arthritis causes inflammation, pain, stiffness, and swelling in joints as well as ligaments and

tendons at their insertion sites. Bone, tendons, enthesis, cartilage, synovial membrane, skin, and nails may all be affected by the condition. During the initial stages, it is the tendons, synovia, and articular capsule that are primarily affected. As the condition progresses, tendon and bone become altered. Marked joint destruction may occur in some individuals.

Psoriatic arthritis is a condition that may often be misdiagnosed due to the wide variety of clinical presentations. Even though it is associated with psoriasis, in 15% of cases arthritis appears first. In cases where psoriasis appears first, it usually occurs 8-10 years before. Mild cases of psoriasis may be incorrectly diagnosed as eczema,

seborrheic dermatitis, or atopic dermatitis. This may further complicate diagnostic accuracy. [2]The Expression of the disease varies greatly from one person to the next. Its course is unpredictable, ranging from mild to severe and destructive. In around 70% of cases, psoriasis precedes arthritis. For the majority, joint symptoms do not appear until approximately ten years after the first signs of psoriasis. Both occur simultaneously in 15% of cases. Extra-articular manifestations of psoriatic arthritis include inflammatory eye diseases, such as vitis and iritis, renal disease, mitral valve prolapse, and aortic regurgitation.[1] The urethra may also become inflamed and fatigue can be a significant problem for people with psoriatic arthritis.[2]

Five Clinical Presentations of Psoriatic Arthritis[edit | edit source]

- Distal Interphalangeal Dominant - Only DIPs of fingers or toes are affected with nail changes often present.

- Symmetric Arthritis - This type resembles rheumatoid arthritis. Five or more joints will be affected in a symmetrical pattern throughout the body.

- Asymmetric Arthritis - This is the most common type making up 70% of cases. Four or less joints are affected in an asymmetrical pattern.

- Spondylitis - This type causes inflammation in the spine. The neck, low back, and SI joints are often affected. It may coincide with symptoms throughout the extremities.

- Arthritis Mutilans - This type is the most severe and destructive. Mutilation of the small joints of fingers and toes often occurs. The fingers may appear sausage-like due to swelling. This is the rarest form, occurring in less than 1% of all cases.[2]

Diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis may often be delayed since there are no identified biomarkers at this time. If left untreated psoriatic arthritis may lead to severe physical limitations and disability. Early diagnosis is critical to slow the progression of the disease with medications.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms[edit | edit source]

- Skin lesions: These include well-defined, dry, red, and usually over-lapping papules and plaques that characterize psoriasis. The patches are usually not itchy and are found most commonly on the extensor surfaces of elbows, knees, back, and buttocks.

- Nail lesions: Include pitting, ridging, brown/yellow discoloration, cracking, separation or loosening of the nails (onycholysis). Presentation of nail impairments may be mistaken for fungal infection and may be the only clinical feature in patients who are more likely to develop arthritis.

- Arthritis: May appear early on and as a severe sign in half of all patients with psoriatic arthritis. Wrists, ankles, knees, and elbows are likely to be involved. The client may report morning stiffness lasting for more than 30 minutes, tenderness, and inflammation.

- Soft-tissue involvement: May include tenderness at the site of tendon insertion or muscle attachment. Commonly seen in the Achilles, plantar fasciitis, and flexor tendons in the hand.

- Dactylitis: This occurs in one-third of the psoriatic arthritis population that presents as swelling of the whole finger making them appear "sausage-like".

- Extraarticular features: Include iritis, urethritis, mouth ulcers, colitis, and aortic valve disease (less common). [4]

Associated Comorbidities[edit | edit source]

- Psoriasis

- Ankylosing Spondylitis (Axial Spondyloarthritis)

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Giant Cell Arteritis

- Sjogren's Syndrome

- Crohn's Disease

- Metabolic Syndrome

- Atherosclerosis

- Coronary Heart Disease

- Depression

Fatigue, anemia, and mood changes can also occur with psoriatic arthritis. If patients have psoriasis they can develop high blood pressure, cholesterol, diabetes, and obesity. [5]

Medications[edit | edit source]

The goal of treatment is to reduce pain, stiffness and swelling, inhibit disease progression, optimize function, decrease the effects of the disease, and improve the patient's quality of life.[6]

Mild Disease[edit | edit source]

- Non-steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDS)

- Local Corticosteroid Injections (must be careful because can cause flare up of psoriasis in some patients.)[6]

NOTE: Neither NSAIDS or intra articular corticosteroids will stop structural joint damage[6]

Moderate to Severe Disease[edit | edit source]

- Disease-Modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD) also called Slow-Acting Antirheumatic Drugs-these drugs will suppress the disease activity (SAARD) www.webmd.com/rheumatoid-arthritis/modifying-medications

- Anti-tumor necrosis factor: should be used if patients do not respond well to NSAIDS or DMARDS. These can include adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab and infliximab[6] www.drugs.com/mtm/infliximab.html,www.drugs.com/cdi/etanercept.html,www.drugs.com/cdi/alefacept.html These drugs which are given intravenously reduce T-cells so that less tumor necrosis factor is released. Both are highly effective but do come with risks since they weaken the immune system.[2]www.psoriasisguide.ca/medical_treatment/immunobiologics/biologic_drugs.html

New Drugs[edit | edit source]

- Otezla is a new drug that has been approved in 2014 for psoriatic arthritis. This drug is an oral phosphodieasterase-4 (PDE-4) inhibitor that will decreases proinflammatory mediators and increases anti-inflammatory mediators.[7]

Treatment Options[edit | edit source]

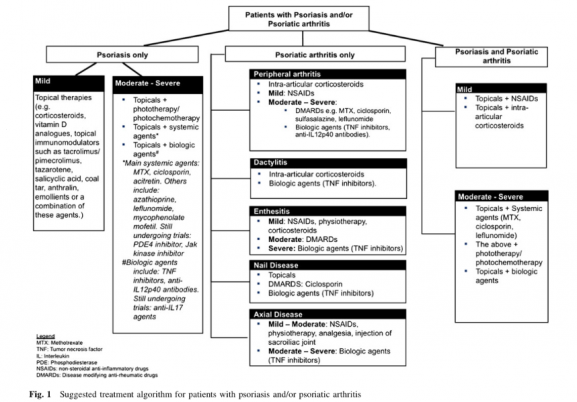

- Not all treatments that target psoriasis can successfully target PsA as well. Therefore, using medications that are beneficial for both psoriasis and arthritic impairments are preferred. Following, is a chart with a proposed algorithm providing recommended treatments for both skin and/or joint diseases based on the impairments of the individual as well as the severity of the diseas. [8]

- Adverse Drug Reactions and Toxicity: Most common reactions are malaise, nausea, and hair loss, but others include liver fibrosis, infection, GI ulcers, elevated transaminases, bone marrow suppression, interstitial pneumonitis, and alveolitis. With proper screening and monitoring liver cirrhosis is less of a risk. Risk factors that may lead to toxicity include DM, obesity, metabolic syndrome, intake more than 3.5-4.0g of methotrexate, alcohol consumption more than 100g per week, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. [8]

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

- There is no definitive test. Diagnosis is made by ruling out other conditions.

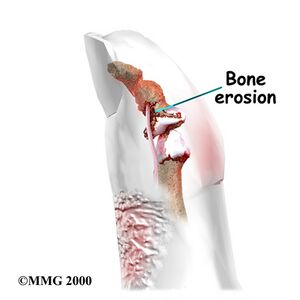

- X-rays are the current gold standard. However, signs of psoriatic arthritis often do not appear on radiographs until later stages of the disease when bone erosion has occured.[9]

- Contrast enhanced ultra sound is starting to play a leading role since it can detect changes in bone and soft tissue much sooner than X-rays.[9]

- Early studies have demonstrated that ultrasound and MRI are both highly sensitive to early inflammatory joint changes that occur in psoriatic arthritis. [9]

- DIP erosive changes on X-rays may support the diagnosis.

- Blood work will be done to detect for the HLA-B27 since it is a common histocompatibility complex marker in people with psoriatic arthritis.

- A blood test for rheumatoid factor should be done to rule out rheumatoid arthritis.

- A blood test for antinuclear antibody (ANA) should be done to rule out Lupus.

- CBC should be done to check for a reduction in red blood cells that sometimes occurs in psoriatic arthritis.[2]

- A joint aspiration may be done in which a syringe removes fluid from a joint. The fluid is then examined for the presence of infection, crystals, and white blood cells.[2]

Causes[edit | edit source]

Genetic[edit | edit source]

Psoriatic arthritis seems to have a genetic cause, although the exact marker genes have not been identified. Having a first-degree relative with psoriatic arthritis increases the likelihood of contracting the disease by 80-90%.[3] There are currently genome studies being done to determine the biomarkers associated with psoriatic arthritis. [10]

Environmental[edit | edit source]

Trauma and infection may trigger the development of psoriatic arthritis.[2]

Immunologic[edit | edit source]

The immune system is believed to play a key role in the development of psoriatic arthritis. Cytokines have been found to be in high abundance in the joints of people with psoriatic arthritis. Cytokines are inflammatory messengers that are released when T cells are activated. Tumor necrosis factor is a specific cytokine that is abundant in the skin, blood, and joints of patients with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis. The job of tumor necrosis factor is to regulate inflammation in the body, and it should be present in low levels. Continued high levels of tumor necrosis factor lead to inflammation in the body. Blocking this particular cytokine often leads to significant improvement in psoriatic arthritis.[2]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

It is ideal for patients to have coordinated care between a dermatologist and rheumatologist since the majority have both skin and joint manifestations of the disease. Since disease manifestations first begin within the skin and nails, it is likely the patient's first point of contact is a dermatologist, putting them in an optimal position to be the first to screen for PsA. There are several screening questionnaires available for PsA including the TOPAS, PEST, PASE, and the EARP, all of which are filled out by the patient. Some of which have been tested to show good sensitivity and specificity.[11]

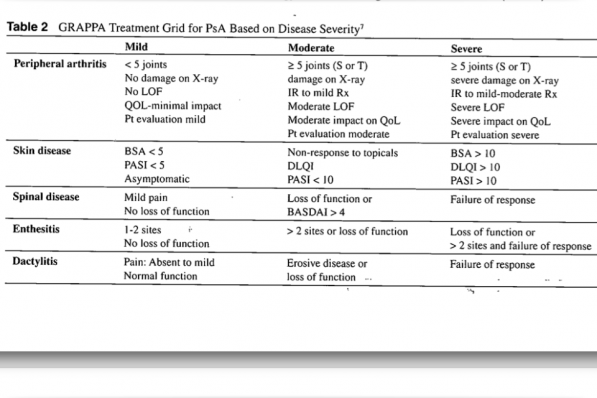

When determining treatment for PsA, an assessment is done to help focus in on the clinical domains present in the patient. They include arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, spondylitis, psoriasis, and nail disease. Usually, measures are used that focus on the skin or joints that result from RA and psoriasis. However, more recently, the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA)have been working on a composite measure that attempts to take the whole patient into account. The measure will allow them to assess the several domains of the disease and monitor its activity as well as the patient's response to therapy. Furthermore, GRAPPA has developed a grid to help determine treatments based on the severity of the disease. Currently, there are two sets of PsA treatments. The first one is the EULAR, which is a set of recommendations to guide the clinician on treatment steps and medication. And the second is the GRAPPA group recommendations, based on a literature review of the treatment of the domains and skin. Treatment choices are based on a grid method that helps the clinician determine disease severity and the impact of the domain on the patients quality of life. [11]

Narrowband UVB light therapy can be very effective in clearing skin lesions. Bulbs with a narrow emission between 311 and 313 nm have been shown in studies to be superior to broadband UVB light. Treatment can be done in an outpatient setting or at home. Both small handheld devices are available as well as larger full-body light units. UV light lamps designed specifically for psoriasis are more effective than commercial tanning beds or sunlight since they give narrowband UVB light. Commercial tanning beds often give off much higher levels of UVA radiation that has been proven to be less effective in treating psoriasis unless combined with psoralen. The Exact ratios of UVA and UVB are very difficult to determine with both sunlight and tanning beds. Generally, light treatments should be done 2-3 times per week for a total of around twenty-five treatments. Skin will be exposed to UVB light from 20 seconds up to around 2 minutes during each treatment based on the Fitzpatrick skin type or minimal erythema dose. [12] www.dermaray.com/

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

The patient should be referred to a rheumatologist immediately if undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis is suspected. All patients with manifestations of arthritic type conditions should be asked if they have any type of skin condition or patches of dry skin. They should also be encouraged to see a rheumatologist that can verify the type of arthritis that they have.

Physical therapy can play an important role in improving the life of a person with psoriatic arthritis. Physical therapy management should focus on education, improvement of range of motion, strengthening, and general cardiovascular conditioning. Physical therapists may also provide UV therapy and modalities to decrease pain. Cryotherapy may help to reduce swelling and tenderness in affected joints. Heat may be used to relieve joint pain. Paraffin baths tend to be soothing for the hands and feet. Splinting may be of benefit to prevent deformity.

Recently studies have shown that hydrotherapy is also an effective treatment for patients with psoriatic arthritis. Hydrotherapy has been shown to improve physical function, energy, sleep and relaxation, cognitive function, work, and participation in patients with psoriatic arthritis.[13]

Living with Psoriatic Arthritis[edit | edit source]

Stiff joints and muscle weakness can occur in patients with psoriatic arthritis due to lack of use. Exercise can be an important intervention that patients can use to prevent or reduce these impairments from occurring. Examples of exercise that can be done include walking (a walking aid or shoe inserts may be needed to decrease the stresses on the affected joint), bikes, yoga, and stretching (for relaxation). Water therapy may also be beneficial, such as swimming or walking laps, in order to decrease the stress on the joints.[5]

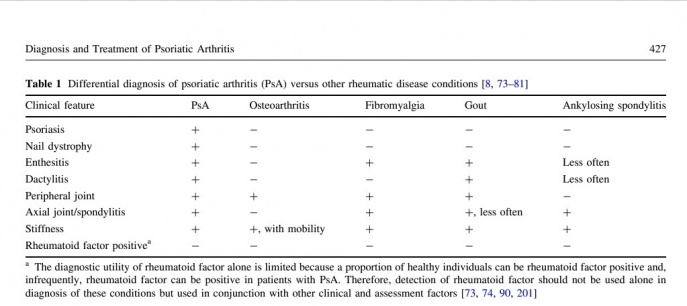

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Osteoarthritis

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Reactive Arthritis

- Gout

- Lupus

- Mallet finger due to traumatic injury

- Ankylosing spondylitis[14]

- Fibromyalgia[14]

Resources[edit | edit source]

Case Reports[edit | edit source]

- Abatacept in psoriatic arthritis: case report and short review[15]

- The development of candidate composite disease activity and responder indices for psoriatic arthritis (GRACE project)[16]

- Treatment of psoriatic arthritis in a phase 3 randomised, placebo-controlled trial with apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor[17]

- Psoriatic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Associated with Uveitis: A Case Report[18]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Goodman C, Fuller K., Soft Tissue, Joint, and Bone Disorders. In: Hart CM, Waltner P, editors. Pathology Implications for the Physical Therapist. St. Louis: Saunders, 2009. P1288-89.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Langley R. Psoriasis: Everything You Need to Know. New York: Firefly Books; 2005.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Fuller KS. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. Third Edition. St.Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

- ↑ Goodman, Catherine. Chapter 12:Screening for Immunologic Disease. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists.2013;374-75

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 American College of Rheumatology. Diseases and Conditions: psoriatic arthritis. http://www.rheumatology.org/Practice/Clinical/Patients/Diseases_And_Conditions/Psoriatic_Arthritis/(accessed 24 Mar 2014).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Waldron N. Care and support of patients with psoriatic arthritis. Nursing Standard 2012;26:35-39. http://rcnpublishing.com/doi/abs/10.7748/ns2012.08.26.52.35.c9247(accessed 20 MAr 2014).

- ↑ Medscape. News: psoriatic arthritis. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/822396 (accessed 24 Mar 2014)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Yiping Gan, Emily, Chong, Wei-Sheng, Tey, Hong Liang, Therapeutic Strategies in Psoriasis Patients with Psoriatic Athritis: Focus on new Agents. BioDrugs 2013 27:359-373.http://eds.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=8ee565f0-094a-4aab-b969-cadd7ab01765%40sessionmgr113&vid=6&hid=116 (accessed 20 MAR 2013)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Solivetti FM, et al. Role of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in early diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis. Dermatology 2010;220:25-31.

- ↑ Castelino M, Barton Anne. Genetic susceptibility factors for psoriatic arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2010;22:152-156.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Mease MD, Philip. Update on Treatment of Psoriatic Arthritis. Bulletin of the NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases 2012; 70(3):167-71.http://eds.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=4&sid=8ee565f0-094a-4aab-b969-cadd7ab01765%40sessionmgr113&hid=116 (accessed 20 MAR 2014).

- ↑ Menter A, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Section 5. Guidelines of care for the treament of psoriasis with phototherapy and photochemotherapy. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2010;62(1):114-135.

- ↑ Lindqvist MH, Gard GE. Hydrotherapy treatment for patients with psoriatic arthritis-A qualitative study. Open Journal of Therapy and Rehab 2013;1:22-30. http://www.scirp.org/journal/PaperInformation.aspx?paperID=39916(accessed 20 Mar 2014).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Armstrong AW, Mease PJ. Managing Patients with Psoriatic Disease: The Diagnosis and Pharmacologic Treatment of Psoriatic Arthritis in Patients with Psoriasis. Drugs 2014;74:423-441. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40265-014-0191-y(accessed 20 Mar 2014).

- ↑ Ursini F, Naty S, Russo E, Grembiale RD. Abatacept in psoriatic arthritis: case report and short review. Journal of Pharmacology & Pharmacotherapeutics. 2013 Dec;4(Suppl1):S29.

- ↑ Helliwell PS, FitzGerald O, Fransen J, Gladman DD, Kreuger GG, Callis-Duffin K, McHugh N, Mease PJ, Strand V, Waxman R, Azevedo VF. [https://ard.bmj.com/content/72/6/986.short The development of candidate composite disease activity and responder indices for psoriatic arthritis (GRACE project)[. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2013 Jun 1;72(6):986-91.

- ↑ Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Gomez-Reino JJ, Adebajo AO, Wollenhaupt J, Gladman DD, Lespessailles E, Hall S, Hochfeld M, Hu C, Hough D. Treatment of psoriatic arthritis in a phase 3 randomised, placebo-controlled trial with apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2014 Jun 1;73(6):1020-6.

- ↑ Moretti D, Cianchi I, Vannucci G, Cimaz R, Simonini G. Psoriatic juvenile idiopathic arthritis associated with uveitis: a case report. Case Reports in Rheumatology. 2013 Jan 1;2013.