Pelvic Congestion Syndrome

Original Editors - Students from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Megan Petty, Cynthia Brown, Elaine Lonnemann, WikiSysop, Kim Jackson, Nicole Hills and Lucinda hampton

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

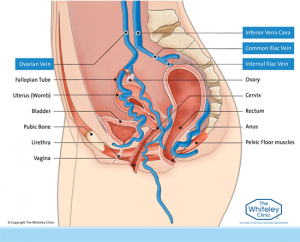

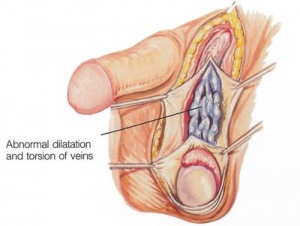

Pelvic Congestion Syndrome (PCS) is a chronic pelvic pain condition in which impaired ovarian veins results in the blood to flow backwards instead of forward, or up, towards the heart[1]. An insufficient or incompetent valve of a vein within the pelvic region is also associated with PCS due to pain occuring from venous distension and congestion [1].The following term and phrase has also been associated with this condition: ovarian variocele and "varicose veins of the ovaries" [1].

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

This condition is most often seen in women who are of childbearing age, or older [1]. Majority of women who are affected have had a history of multiple pregnancies [1]. This syndrome can also occur in men and is diagnosed through presentation of visible varicosities on the scrotum cavarello[1]. Furthermore, it is the cause of about 10-15% of referrals to gynecologists or other pain related clinics [2].

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation

Pelvic Congestion Syndrome may be asymptomatic and often times may go undiagnosed[2]. This condition can cause continuous or intermittent lower abdominal or pelvic pain, ranging from a dull ache to a sharp severe pain [1]. Duration of pain can last more than 6 months [3]. The lower abdominal, or pelvic, pain associated with PCS can be felt unilaterally,on one side, or bilaterally [1]. The pain usually is worse by the end of the day, and also with long periods of standing or sitting [3]. Furthermore, the pain can be related to the onset of mensus [1] [3].

Additional symptoms associated with PCS are outlined below:

- Tenderness upon deep palapation of the ovarian point[1]

- Dyspareunia[1]

- Presence of varicose veins in the buttock and/or lower extremities[1]

- Headache[1]

- Gastrointestinal pain/discomfort[1]

- Changes in bowel and bladder[1]

- Fatigue[1]

- Insomnia[1]

- Heaviness feeling felt in the lower abdomen or pelvic region[1]

- Lower back pain worsened upon standing upright[1]

- Lethargy[3]

- Depression[3]

- Vaginal discharge[3]

- Dysmenorrhea[3]

- Swollen vulva[3]

- Lumbosacral neuropathy[3]

- Rectal discomfort[3]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Impaired circulatory function, such as peripheral vascular disease, is often associated with PCS [1].

Medications[edit | edit source]

Patients with PCS can often be prescribed hormonal medications [2](4). This pharmacological management of this condition is directed towards decreasing congestion from the varicose veins, and also decreasing blood flow to the varicose veins[4] (5).

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

Pelvic Congestion Syndrome is often missed due to the supine positioning, typically used for testing, which may cause a decrease in venous distention [3]. Presence of PCS may be found through laproscopy, hysteroscopy, or other imaging (i.e. computerized tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasound)[2]. The gold standard treatment of PCS, to date, is pelvic venography [5].

Ignacio et al. [3] found two primary imaging modalities utilized to provide further information of venous blood flow and detecting presence varicose veins in the pelvic region, which include:

- Pelvic Ultrasonography which provides a more dynamic image of the blood flow, and

- Computed tomography used for detecting varicose veins in the lower abdominal region, and is more sensitive than ultrasound

Ignacio et al also came up with criteria for sonographic diagnosis [3]:

- Ovarian veins >4mm in diameter

- Dilation of and tortuous Arcuate veins that communicate with bilateral pelvic veins, and

- Retrograde, and decreased blood flow of < 3cm/s (particularly of the left ovarian vein)

Etiology/Causes[edit | edit source]

Women birthing two or more children (multiparous) can become more susceptible to developing PCS [3]. With each pregnancy, a woman's intravascular volume can significantly increase up to sixty percent[3]. As intravascular volume increases, so can venous distension [3]. If an ovarian vein is subject to excessive distension, valvular incompencies can occur and result in PCS [3]. It has also been suggested that estrogen can play a role in the weakening of venous walls, so careful consideration should be taken when hormones are being medically managed [3].

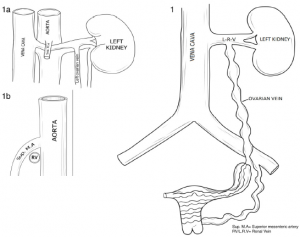

Another cause of PCS can be anatomic anomalies that become obstructing in nature. A retroaortic renal vein can result in an obstruction of an ovarian vein, and thus pelvic varices [3]. Compression from the superior mesenteric artery can occur on the renal or ovarian vein. This particular compression has been described in the literature as "Nutcracker Syndrome" [3]. Additional compression from the common iliac artery can occur on the common iliac vein between the spine and the pelvic brim. The resulting compression cascade can produce pelvic varices or even iliofemoral deep venous thrombosis[3].

Additionally, surgical complications can lead to the incidence of PCS. The most known surgical association is with a nephrectomy. During this procedure, the ovarian vein is an an increased risk of being cut[1].

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

To date, PCS is not known to lead to any systemic involvement.

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Analgesics including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, for pain management, are the first line of treatment for PCS[5]. Referral to an interventional radiologist may be indicated if symptoms do not resolve or improve with medication[5]. The most succesful medical treatment option for PCS is embolization of the malfunctioning vessels, with a success rate of 98-100% [5]. Embolization of varices is an outpatient procedure, performed by an interventional radiologists, that can reduce or resolve symptoms related to PCS. This procedure is performed only after a thorough history, physical exam, and review of imaging has been performed by the physician [5]. The procedure is performed while sedated, with local anesthetic, and is guided through imaging[5]. Reduction in symptoms can be expected 2-4 weeks post operatively and has been shown in 75-80% of women studied [5].

Ignacia and colleagues[3] mentioned several medical treatements for PCS that include [3]:

- Hormone analogues

- Surgical ligation of ovarian veins

- Hysterectomy

- Transcatherter embolization

- Psycho therapy

- Progestins

- Phlebotonics

- Gonadotropins receptor agonists (GnRH) with hormone replacement therapy (HRT)

- Dihydroergotamine

- NSAIDS

Physical Therapy Management)[edit | edit source]

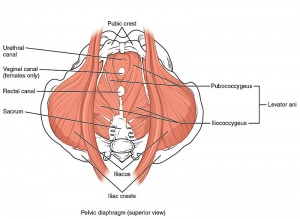

To date, there is currently not any literature investigating the role of physical therapy in PCS management. Regardless, a person may seek out a physical therapist specialized in pelvic dysfunction due to their chronic pain or incontinence issues. A physical therapist will be able to conduct a thorough evaluation, and design a rehabilitation program based off of a person's impairments. Often due to the close proximity of PCS, the pelvic floor musculature can be affected. In this instance, physical therapists can provide specific exercises to improve optimal performance of the pelvic foor musculature.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Due to clinical presentation, PCS has an extensive list of differential diagnosis to be ruled out prior to the diagnosis.

- Bowel Pathology[3]

- Cancer[3]

- Endometriosis[3]

- Fibroids[3]

- Fibromyalgia[3]

- Ovarian Cyst[3]

- Pelvic Inflammatory Disorder[3]

- Porphyria[3]

- Uterine Prolapse[3]

- Orthopedic, Neurologic, or Urogenic Pathology[3]

- Leiomyoma[5]

- Adenomyosis[5]

- Nutcracker Syndrome[5]

- Inflammatory Bowel Syndrome[5]

- Diverticulitis/Diverticulosis/Meckel's Diverticulum[5]

- Interstitial Cystitis[5]

- Fascitis[5]

- Psychosexual Dysfunction[5]

- Depression[5]

Case Reports/ Case Studies[edit | edit source]

- Thorne C, Stuckey B. CASE REPORT: Pelvic Congestion Syndrome Presenting as Persistent Genital Arousal: A Case Report. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2008;5(2):504-508.

- Machan L, Durham J. Pelvic Congestion Syndrome. Semin intervent Radiol. 2013;30(04):373-380.

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 Goodman CC and Snyder TEK. Differential diagnosis for physical therapists: Screening for referral, 5 ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier ; 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Pelvic Congestion Syndrome (PCS). https://stanfordhealthcare.org/medical-conditions/womens-health/pelvic-congestion.html (accessed 18 March 2016)

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 3.24 3.25 3.26 3.27 3.28 3.29 3.30 3.31 3.32 Ignacio EA, Dua R, Sarin S, Harper AS, Yim D, Mathur V, et al. Pelvic congestion syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Seminars In Interventional Radiology 2008; 25(4): 361- 368.

- ↑ Treatment options for PCS https://stanfordhealthcare.org/medical-conditions/womens-health/pelvic-congestion/treatments.html (accessed 4 April 2016)

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 Semmel D. Options for pelvic congestion syndrome. Clinical Advisor 2013;. http://www.clinicaladvisor.com/features/options-for-pelvic-congestion-syndrome/article/311435/ (accessed 20 March 2016)