Pain Management of the Amputee

Original Editor - Peter Le Feuvre as part of the World Physiotherapy Network for Amputee Rehabilitation Project

Top Contributors - Admin, Kim Jackson, Aicha Benyaich, Tony Lowe, Tarina van der Stockt, Melissa Coetsee, Evan Thomas, Kirenga Bamurange Liliane, Aya Alhindi and Bruno Serra

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Pain is an inevitable consequence of amputation. There are several types of sensations following an amputation that should be discussed when referring to pain following amputation. Some of them are extremely painful and terribly unpleasant; some are simply weird or disconcerting. In one form or another they are experienced by most people following an amputation.

Why Does Pain Occur?[edit | edit source]

Peripheral neuropathic mechanisms:

- Immediate nerve injury discharge.

- Local nociceptive substances.

- Deafferentation.

- Ectopic firing.

- Neuromas.

- Ephatic transmission b/w sensory and sympathetic fibres.

Spinal cord:

- Expansion of receptive fields.

- Low-threshold inputs when high-threshold inputs lost.

- Disinhibition.

Brain:

- Cortical engram generates pain in absence of stimuli.

- Cortical reorganisation.

Non-neurological factors:

- Skin blood flow.

- Stump temperature.

- Muscle tension.

Psychological factors:

- Stressors/ depression/anxiety

- Not personality types

Intrinsic pain[edit | edit source]

- Post amputation pain can be isolated to the residual limb or can occur as phantom pain. For many, pain will not just result from the trauma of the surgery, but will also include a neuropathic presentation known as Phantom Limb Pain (PLP).

- When amputation has resulted from a traumatic incident, such as in a disaster setting, this can be complicated by co-existing injury to the same limb or other parts of the body. For the physiotherapists involved in the early and post acute stages of rehabilitation, the challenge is determining the nociceptive and neuropathic causes which require attention in order to manage the patient and so enable effective rehabilitation to occur.

- Post-Amputation Pain: Post-amputation pain at the wound site should be distinguished from pain in the residual limb and the phantom limb. After amputation, all three may occur together[1]

- Residual Limb Pain (RLP): Patients can often feel pain or sensations in the areas adjacent to the amputated body part. This is known as residual limb (RLP) or stump pain. It is often confused with and its intensity is often positively correlated with PLP[2].

- Phantom Limb Sensation: This is a normal experience for the majority of amputees, but it is not a noxious sensation, which might be described by the patient as unpleasant. Often it can be described as a light tingling sensation, or in such cases re-assurance is the key[3].

- Phantom Limb Pain (PLP): Classified as neuropathic pain, whereas RLP and post-amputation pain are classified as nociceptive pain. PLP is often more intense in the distal portion of the phantom limb and can be exacerbated or elicited by physical factors (pressure on the residual limb, time of day, weather) and psychological factors, such as emotional stress. Commonly used descriptors include sharp, cramping, burning, electric, jumping, crushing and cramping.

In addition to these 4 pain types that can be experienced following amputation, clinicians should also be aware of pain that may be caused by co-existing pathology:

- Vascular pain - such as exercise induced claudication or pain caused by vascular disease

- Musculoskeletal pain - pain from other injuries suffered during a traumatic amputation, musculoskeletal pain caused by abnormal gait patterns pain caused by normal ageing processes, or excessive wear and tear on the joints and soft tissue of the residual limb.

- Neuromas - localized pain, sharp/shooting/paraesthesia reproduced by local palpation and Tinel's sign, relieved by LA injection.

Pathophysiological mechanisms of Acute and Chronic Phantom Limb Pain[edit | edit source]

Acute PLP[4][edit | edit source]

Amputation site:

- Tissue and Neuronal injury.

- Hyperexcitability.

- Spontaneous discharge.

Brain:

- Increased neuronal activity.

- Hyperexcitability.

- Loss of descending inhibitory pain pathway.

- Expansion of neuronal receptive field.

Spinal cord:

- Increased NMDA Receptor activity mediated by substance P tachvkinin and neurakinins.

- Non-pain neurons sprout into dorsal horn.

Chronic PLP[4][edit | edit source]

Amputation site:

- Stump and neuroma formation.

- Deafferentation pain.

Brain:

- Cortical reorganisation.

- Cortical motor-sensory dissociation.

- Abnormal neuromatrix and neurosignature.

Spinal cord:

- Spinal cord sensitisation.

- Wind up phenomena.

Extrinsic causes of pain[edit | edit source]

Prosthetic pain is also a concern and may be caused by:

- Ill-fitting socket : lack of distal contact, insufficient bony relief, too tight, too loose, pistoning causing friction / blisters

- Incorrect alignment and pressure distribution

- Incorrectly donned prosthesis, including the number / thickness of socks

- Excessive sweating / skin breakdown

- Verrucous hyperplasia

Assessment[edit | edit source]

Assessment should seek to establish the type of pain present.

In addition to completing a pain chart, measurement of pain intensity is objectively helpful.

- The brief pain inventory (BPI): is one method of charting the intensity of symptoms, however it takes time to administer.

- The 0-3 VAS: is an easy to administer scale which highlights when intervention is required.

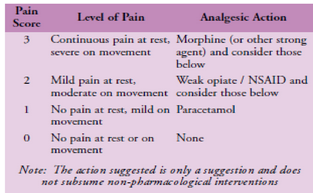

- WHO pain ladder (Figure 1).

Scores of:

- 0 and 1 (nil to mild pain)- require no intervention

- 2 and 3 (moderate to severe)- requires immediate action[3][5].

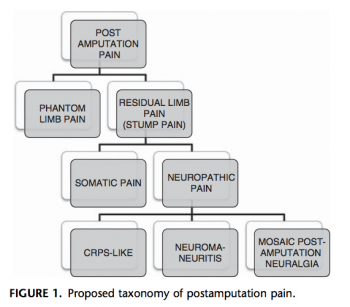

See the image below for the proposed taxonomy for post-amputation pain.[6]

Treatments[edit | edit source]

A large variety of medical/surgical and non-medical methods exist for the treatment of post-amputation pain:

- Adequate post-op analgesia.

- Patient education.

- Limit oedema.

- Prevent contractures.

- Address musculoskeletal weakness and imbalances.

- Desensitisation - massage/bandaging.

- Get patient moving, distraction helps.

- Early prosthetic training.Below Peter Le Feurve, a physiotherapist with an interest in pain talks about pain management in amputees:

Virtual Reality (VR)[edit | edit source]

Virtual reality(VR) is a new technology being investigated as a possible treatment for PLP. VR produces a simulated world in which a person can be immersed in a different reality. VR can assist persons with PLP in visualising and controlling their missing limb. VR is an exciting new therapy option for PLP. It is a non-invasive and safe treatment that can help patients with this ailment enhance their quality of life. More research is needed to validate the effectiveness of VR for PLP, however the findings of previous trials are encouraging.[7]

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Phantom Limb Pain

- Mirror Therapy

- Pain management. Australian Physiotherapists in Amputee Rehabilitation..

- Pain management for patients. National Limb loss information center.

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for phantom pain and stump pain following amputation in adults (Review). Mulvey MR, Bagnall AM, Johnson MI, Marchant PR, Cochrane Library, 2010, Issue 5.

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for chronic pain (Review). Nnoaham KE, Kumbang J. Cochrane collaboration, 2014, Issue 7

- Phantom Limb Pain. L. Nikolajsen and T.S. Jensen. Br J Anaesth, 2001, 87(1):107-16

- Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation for Phantom Pain and Stump Pain in Adult Amputees Matthew R. Mulvey, Helen E. Radford, Helen J. Fawkner, ynn Hirst, Vera Neumann, Mark I. Johnson. Pain Practice, 2013, 13(4):289–296

- Privitera R, Birch R, Sinisi M, Mihaylov IR, Leech R, Anand P. Capsaicin 8% patch treatment for amputation stump and phantom limb pain: a clinical and functional MRI study. Journal of pain research. 2017;10:1623.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ CM, Kooijmana Dijkstra PU, Geertzena JHB, et al. Phantom pain and phantom sensations in upper limb amputees: an epidemiological study. Pain 2000;87:33–41

- ↑ MacIver K, Lloyd DM, Kelly S, et al. Phantom limb pain, cortical reorganization and the therapeutic effect of mental imagery. Brain 2008;131:2181–91.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Le Feuvre P, Aldington D. Know Pain Know Gain: proposing a treatment approach for phantom limb pain. J R Army Med Corps 2014; 160(1):16-21 http://jramc.bmj.com/content/160/1/16.full.pdf+html

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Ahuja V,Thapa D,Ghai B.Strategies for prevention of lower limb post-amputation pain:a clinical narrative review.J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol.2018;34(4):439-449.

- ↑ Looker J, Aldington D, ‘Pain Scores - As Easy as Counting to Three.’ J R Army Med Corps 2009;155:1 42-43

- ↑ Collin Clarke, MD, David R. Lindsay, MD,Srinivas Pyati, MD, and Thomas Buchheit, MD, 2013, Residual A Proposed Algorithm to Classify Postamputation Pain, Clin J Pain 2013;29:551–562

- ↑ Paxton, G. (2023). The potential of virtual reality to improve the quality of life for people with phantom limb pain (NON-THESIS). Concordia University St. Paul.