Paediatric Conditions of the Foot

Top Contributors - Stacy Schiurring, Jess Bell and Kim Jackson

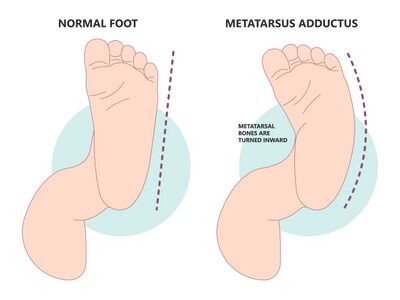

Metatarsus Adductus (Metatarsus Varus)[edit | edit source]

"Metatarsus adductus primarily involves medial deviation of the forefoot on the hindfoot." - Pediatric Orthopedic Society of North America (POSAN)[1]

Secondary characteristics include:

- prominence of the 5th metatarsal base[1]

- neutral[2] to slightly valgus hindfoot[1]

- slightly supinated forefoot[1]

- a possible widening of the space between the 1st and 2nd toes[1]

- many patients also have internal tibial torsion[1]

- no ankle range of motion (ROM) restrictions[2]

Metatarsus adductus can be classified based on degree of foot flexibility:[3]

- Flexible: the heel and forefoot can be easily moved into proper alignment using gentle manual manipulation

- Semi-flexible: the feel and forefoot can be realigned to a certain degree using gentle manual manipulation

- Rigid / non-flexible: when the heel and forefoot cannot be realigned using gentle manual methods

Incidence: 1/1,000 live births.[1][2]

Aetiology:

- In utero compression

- Embryologic or congenital abnormalities[2]

Assessment[edit | edit source]

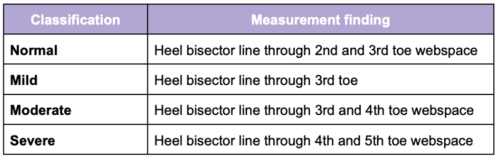

- Bleck’s Heel Bisector Line (HBL) is a simple measure that assesses the flexibility and severity of metatarsus adductus. It is a manual assessment. No special equipment is needed to complete this assessment. This method has been used for over four decades, with some modifications. However, recent research has shown that this method can be unclear and has the potential for measurement errors when measuring the heel bisector line (HBL).[4] The procedure is as follows.

- The shape of the weight-bearing foot is obtained. Traditionally, a mould of the weight-bearing foot is made; modifications include using footprints or photos of the weight-bearing foot.[4] Another option includes placing the child in prone with their knees flexed to 90 degrees and the plantar surface of the foot parallel to the ceiling.[2]

- The procedure is completed by determining the longitudinal axis of the ellipse with a straight edge, independent of the forefoot.[4]

- According to Bleck’s method, classification depends on where the HBL crosses the metatarsal heads (see table above).[4]

- Transmalleolar Axis Bisector (TMAB) is a newly proposed alternative assessment technique for measuring the severity of metatarsus adductus.[4] The procedure is described below.[4]

- The child is in prone with their knees flexed to 90 degrees and the plantar surface of their foot parallel to the ceiling. Weight-bearing of the foot is approximated by maintaining the ankle in a plantigrade position.

- Using a pair of vernier calipers, a line is drawn across the heel, connecting the most medial point of the medial malleolus to the most lateral point of the lateral malleolus. The midpoint of this line is marked.

- A goniometer is then placed on the foot, with the axis on the marked midpoint and the stationary arm aligned on the drawn line. The moveable arm is placed at 90 degrees to the stationary arm. The moveable arm delineates the TMAB.

- Classification of metatarsus adductus relates to where the TMAB crosses the metatarsal heads. There are currently no classification norms using this method as research is ongoing. Researchers recommend recording TMAB location results with descriptors such as "at the second interdigital web space" or "third digit" or "third interdigital web space."

Intervention[edit | edit source]

- Mild cases: typically resolve without intervention[2]

- Moderate cases: [2]

- stretching exercises

- corrective shoes

- straight last

- reverse last

- Severe cases might need:[2]

- manipulation

- serial casting followed by corrective shoes

- surgery should not considered before the age of four to allow for spontaneous resolution

Pes Planus (Pes Planovalgus or Flat Foot)[edit | edit source]

Pes planus is "defined by the loss of the medial longitudinal arch of the foot where it contacts or nearly contacts the ground."[5] It can occur with or without further deformities of the foot and ankle.[6]

Pes planus can be divided into two types:

- Flexible: where the medial longitudinal arch of the foot is present on heel elevation (tiptoe standing) and non-weight bearing but disappear with full weight bearing on the foot.[7] Most typically developing infants are born with flexible flat feet. Arch development is first seen around three years of age, with adult values in arch height developing between seven and ten years of age.[5][8]

- Rigid: where the medial longitudinal arch of the foot is absent in both heel elevation (tiptoe standing) and weight bearing. This is normally associated with underlying pathology,[9] such as vertical talus or tarsal coalition.[6]

Incidence: 7 to 22% of the general population.[2]

Aetiology:

- Congenital: most infants have flat feet due to ligamentous laxity and developing neuromuscular control. Only a small percentage of children fail to develop normal arches. Children with Down Syndrome, Marfan Syndrome, or Ehlers-Danos Syndrome can be prone to congenital ligamentous laxity.[5]

- Acquired: most commonly associated with posterior tibial tendon dysfunction, which is most common in females over the age of 40 who have comorbidities, such as diabetes and obesity.[5]

Factors that can contribute to an increased flat foot:

- Little time spent barefoot, resulting in weak foot intrinsic muscles and poor foot arch development.[2]

- Childhood obesity.[2][5]

Assessment[edit | edit source]

- Significant malalignment with or without associated pain:

- presence of an accessory navicular bone

- Lack of mobility:

- need to rule out tarsal coalition with rigid or limited subtalar motion

- A full-body postural assessment can also be useful to rule out issues further up the kinetic chain

- Neurological screen[2]

Intervention[edit | edit source]

"... we don't need to correct if they don't have pain, if there's no problem with their gait, or their ability to participate in activities of interest. " -Krista Eskay, PT[2]

Rehabilitation Interventions:

- Pain management

- Stretching/increasing ankle flexibility

- Strengthening foot intrinsics and ankle muscles

- Proprioceptive training

- Family education and reassurance

Providing additional support:

- Shoes with arch support: this will not correct the deformity but will provide additional stability and can result in improved mobility and gait

- Orthotics

When to refer:

- To an orthopaedist:

- if the longitudinal arch of the foot is absent on heel elevation or is asymmetrical

- there is significant pain affecting activities of daily living or mobility

- To a neurologist:

- abnormal neurological screen

- if the child is under five years of age and has pain in their knees, hips and feet

- To a physical medicine specialist:

- if the child is under five years of age and has pain in their knees, hips and feet

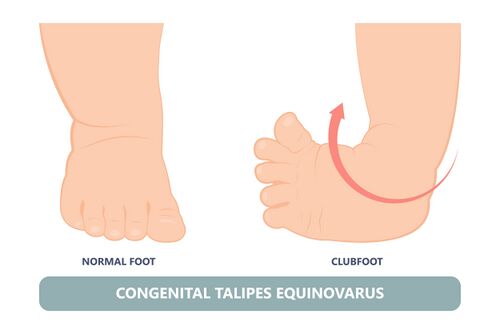

Clubfoot (Talipes Equinovarus)[edit | edit source]

Clubfoot "is one of the most common congenital malformations and is characterized across varying degrees and severity of predictable contractures manifesting with four main components: (1) midfoot cavus, (2) forefoot adductus, (3) heel/hindfoot varus and (4) hindfoot equinus."[10]

- Occurs twice as often in males as in females[10]

- Can be unilateral or bilateral:[2]

- The involved foot can be smaller and shorter in size[2]

- The clubfoot will have an empty heel pad[2]

- Transverse plantar crease present[2]

Incidence: 1/1,000 live births.[2][11]

Aetiology:

- Idiopathic: approximately 80% of cases

- Other cases tend to be associated with disorders such as Spina Bifida, Cerebral Palsy and Arthrogryposis[12]

Assessment[edit | edit source]

When assessing the foot, there are several distinctive deformities associated with clubfoot.[10][13]

- Midfoot cavus

- Forefoot adductus

- Hindfoot varus

- Hindfoot equinus

These malformations can present with a range of orthopaedic deformity and degree of stiffness.[10] Several scoring systems exist[2] and can be used to help in assessing and classifying the degree of deformity present. According to the literature, there is no gold standard grading method for assessing or monitoring the degree of deformity associated with clubfoot.[13]

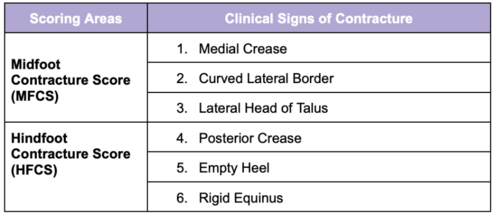

Pirani Scoring System[edit | edit source]

The Pirani Scoring System is based on six well-described clinical signs of contracture characterising a severe clubfoot.[14] This scoring system quantifies the degree of clubfoot deformity.[15]

- If the sign is severely abnormal, it scores 1

- If it is partially abnormal, it scores 0.5

- If it is normal, it scores 0

The midfoot and hindfoot are evaluated separately. The Midfoot Contracture Score (MFCS) includes the medial crease, lateral edge convexity (also called curved lateral border), and the lateral talus head position. The Hindfoot Contracture Score (HCFS) includes the posterior crease, empty heel, and rigid equinus.[15] The six areas assessed include three signs from the midfoot and three signs from the hindfoot. The six areas are scored as described above, then the scores are summed to a Total Score, which ranges from 0-6. The higher the score, the more severe the presentation.[14]

The assessment is performed with the examiner in sitting. The infant is on the mother’s lap. It is easier to perform a precise examination if the infant is feeding and relaxed. The measurements are made while the examiner gently corrects the foot with minimal effort, and no discomfort.[14] For more information on using this scoring system, please read this article. For a clinical example, please see this article

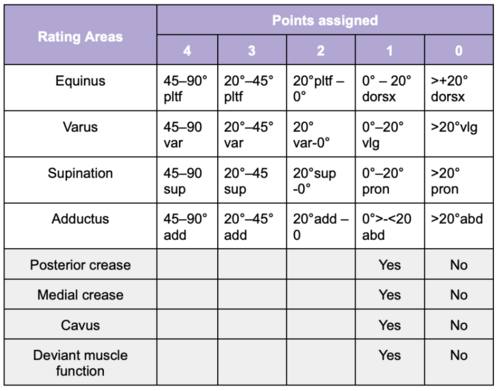

Dimeglio Classification Scoring System[edit | edit source]

Dimeglio Classification Scoring System is based on 8-rated areas characterising clubfoot. It focuses on assessing the degree of rigidity of the foot.[15][16] This scoring system distinguishes four basic parameters: (1) equinosity in the sagittal plane, (2) varus deviation in the frontal plane, (3) deformation of the block calcaneus and forefoot, and (4) adduction of the forefoot in the horizontal plane, evaluated on a scale from 0 to 4 points.[15] Next, an additional four adverse symptoms are assessed: (1) posterior crease, (2) medial crease, (3) cavus deformity, and (4) calf hypotrophy (deviant muscle function). These four symptoms are rated one point each.[15]

The total score ranges from 0-20. The higher the score, the more severe the presentation.[16]

- most severe: 16–20

- severe: 11–15

- moderate: 6–10

- postural: 0–5

Interventions[edit | edit source]

"The purposes of clubfoot therapy are to achieve and maintain clubfoot correction, so that the patients have functional, painless, plantigrade feet with good mobility" - Ponseti and Campos, 2009[13]

The Ponseti Method is the gold standard treatment for clubfoot deformity. This treatment method was developed in response to the complications and poor outcomes that came with the surgical management of clubfoot.[17] Treatment occurs over two phases: treatment phase and maintenance phase.

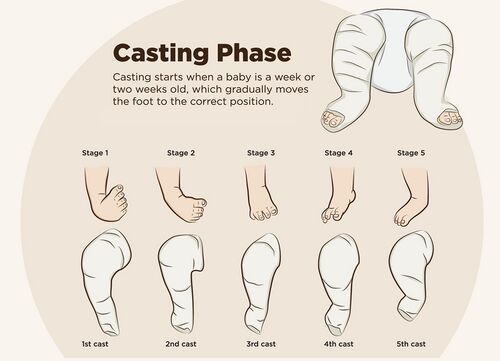

- Treatment (Casting, Corrective) Phase is when the deformity is physically corrected by gentle mobilisations, and serial casting:[2]

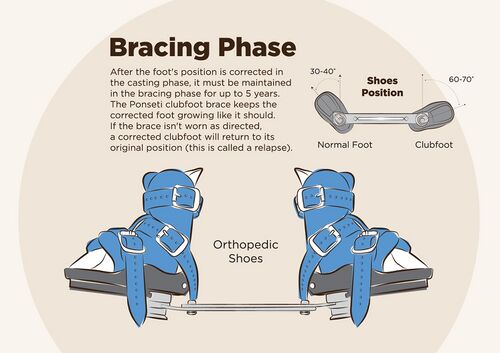

- Maintenance (Bracing) Phase involves a strict and scheduled bracing protocol to prevent deformity reoccurrence as the infant continues to grow[2]

- an orthotic brace must be worn for 23 hours per day for three months

- the wearing schedule decreases to nightly for multiple years

- adherence and carryover can be challenging for families to complete

- inability to carryover properly and correctly in this phase in its entirety can result in recurrence of the clubfoot deformity

- Percutaneous Achilles Tenotomy surgery is indicated in 90% of cases[14]

- corrects remaining rigid equinus

- involves a complete cut through the Achilles tendon, not a tendon lengthening

- the tendon heals sufficiently in approximately three weeks.

The procedures described above require advanced in-person training to perform them safely. It is not recommended that rehabilitation professionals perform serial casting without proper training due to the risk of pressure injury and wound formation. For a general overview of casting for clubfoot, please read this article.

Special Topic: The Role of the Rehabilitation Professional in Clubfoot Interventions[edit | edit source]

In addition to assisting in any part of the Ponseti Method, which requires advanced training, a rehabilitation professional has a large and important role to play in the effectiveness of clubfoot interventions.

- Monitoring for clubfoot deformity recurrence: Approximately a third of infants who complete the Ponseti Method for the treatment of clubfoot will experience a deformity relapse. Rehabilitation professionals are integral to monitoring and reassessing the feet of these patients for signs of reoccurrence and to refer appropriately. Reassessment and supervision for clubfoot deformity recurrence needs to continue, potentially for many years following treatment, until the child is past their initial growth years.[18]

- Family/caregiver training and support: The maintenance phase of clubfoot treatment can continue for many years and requires strict wearing of nighttime braces or orthotics. The family/caregiver is likely to face fatigue and decreased protocol carryover.[2] It is important to provide education and support on the possibility of late relapses.[18]

- A 2020 study[19] found, especially in low- to middle-income countries, barriers such as (1) long travel distance and time to clinic, (2) lack of familial support, and (3) challenges with family's other commitments prevent treatment completion and increase drop-out rates. Providing support such as (1) appointment reminders, (2) family support groups and (3) financial support for travel and treatment have all been found to be effective in improving treatment completion.[19]

Resources[edit | edit source]

Clubfoot Support Groups and Online Resources[edit | edit source]

Clinical Resources[edit | edit source]

- Clubfoot C.A.R.E.S. Boot donation and need requests (United States)

- Ponseti International(free downloads in English, Spanish, Thai, Turkish, Portuguese, and trial in Chinese)

- In-depth review of foot and ankle anatomy

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America (POSNA). Metatarsus Adductus. Available from: https://posna.org/physician-education/study-guide/metatarsus-adductus (accessed 29 October 2023).

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 Eskay K. Paediatric Physiotherapy Programme. Paediatric Conditions of the Foot Course. Plus. 2023.

- ↑ Gonzales AS, Saber AY, Ampat G, Mendez MD. Intoeing.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Alonge VO. Proposing Transmalleolar Axis Bisector (TMAB) as a Geometrically Accurate Alternative to the Heel Bisector Line for the Clinical Assessment of Metatarsus Adductus. Int J Foot Ankle. 2020;4:041.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 National Institute of Health, National Library of Medicine. StatPearls | Pes Planus. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430802/#:~:text=Pes%20planus%20commonly%20referred%20to,fascia%20between%20the%20forefoot%20and (accessed 14 November 2023).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 KAYMAZ B. Pediatric Pes Planus (flatfoot). Family Practice and Palliative Care. 2022 Oct 19;7(4):118-23.

- ↑ Kothari A, Bhuva S, Stebbins J, Zavatsky AB, Theologis T. An investigation into the aetiology of flexible flat feet: the role of subtalar joint morphology. A The Bone & Joint Journal. 2016 Apr;98(4):564-8

- ↑ Squibb M, Sheerin K, Francis P. Measurement of the Developing Foot in Shod and Barefoot Paediatric Populations: A Narrative Review. Children. 2022 May 19;9(5):750.

- ↑ Halabchi F, Mazaheri R, Mirshahi M, Abbasian L. Pediatric flexible flatfoot; clinical aspects and algorithmic approach. Iranian journal of pediatrics. 2013 Jun;23(3):247.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Barrie A, Varacallo M. Clubfoot. InStatPearls [Internet] 2022 Sep 4. StatPearls Publishing.

- ↑ Dibello D, Di Carlo V, Colin G, Barbi E, Galimberti A. What a paediatrician should know about congenital clubfoot. Italian Journal of Pediatrics. 2020 Dec;46(1):1-6.

- ↑ Bridgens J, Kiely N. Current management of clubfoot (congenital talipes equinovarus). BmJ. 2010 Feb 2;340(6):c355.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Martanto TW, Dominica H, Irianto KA, Bayusentono S, Utomo DN. The pirani score evaluation on patients with clubfoot treated with the ponsety method in public hospital. EurAsian Journal of BioSciences. 2020;14(2):3419-22.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Africa Clubfoot Training Project. Chapter 4 Africa Clubfoot Training Basic & Advanced Clubfoot Treatment Provider Courses - Participant Manual. University of Oxford: Africa Clubfoot Training Project, 2017.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Jochymek J, Peterková T. Are scoring systems useful for predicting results of treatment for clubfoot using the ponseti method?. Acta Ortopédica Brasileira. 2019 Jan;27:8-11.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Andriesse H, Roos EM, Hägglund G, Jarnlo GB. Validity and responsiveness of the Clubfoot Assessment Protocol (CAP). A methodological study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2006 Dec;7(1):1-9.

- ↑ Gerlach, D.J., Gurnett, CA.,Limpaphayom, N.,Alaee, Farhang.,Zhang, Z.,Porter, K.,Smyth, M. D Dobbs, Matthew B 2009. Early results of the Ponseti method for the treatment of clubfoot associated with myelomeningocele. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume, 91, pp.1350–1359

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Agarwal A, Rastogi A, Rastogi P, Deo NB. Relapses in clubfoot treated with Ponseti technique and standard bracing protocol-a systematic analysis. Journal of clinical orthopaedics and trauma. 2021 Jul 1;18:199-204.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Evans A, Chowdhury M, Karimi L, Rouf A, Uddin S, Haque O. Factors affecting parents to ‘Drop-Out’from ponseti method and children’s clubfoot relapse. 2020.