Introduction to Basic Rehabilitation Techniques

Original Editors - Naomi O'Reilly and Jacquie Kieck

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Ewa Jaraczewska, Jess Bell, Tarina van der Stockt, Tony Lowe, Bruno Serra and Lucinda hampton

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Rehabilitation is a widely discussed concept. This is by no means unexpected since approximately 1.5 billion people worldwide (i.e. 15% of the world's population) live with some form of disability.[1] Furthermore, according to a recent report,[2] 2.41 billion individuals live with conditions that impact their function in daily life and would benefit from rehabilitation services - this equates to 1 in 3 individuals requiring rehabilitation services throughout their illness or injury.[3]

Access to rehabilitation services can help people to live longer, healthier lives with their disability. Rehabilitation should be prioritised in all countries, regardless of socioeconomic status. It should not be considered a specialised or expensive service, especially when it is integrated with community and primary care.[2] To achieve this, healthcare professionals must continuously evaluate the assessment tools they use and the rehabilitation techniques and interventions they choose.

This article will discuss the relationship between the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), clinical assessment and the selection of rehabilitation techniques and interventions.

Definition of Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

The term "rehabilitation" is used in many different contexts. Currently, there is no universal definition or understanding of rehabilitation; it is portrayed in many ways depending on the context, including as a development issue, disability issue, health issue, human rights issue, substance abuse issue, and security issue, to name a few. A general underlying principle of rehabilitation is the idea that each person has the right to be an active participant and expert in identifying their needs and making decisions about their health care.

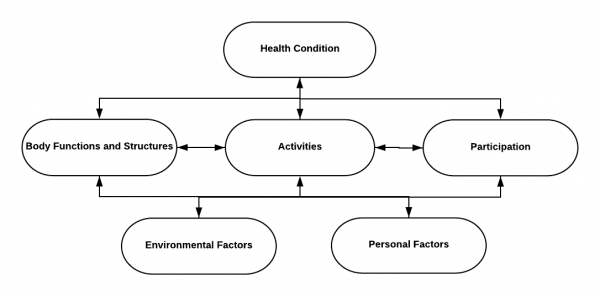

If we consider the definition of rehabilitation promoted by the World Health Organization as "a set of measures that assist individuals who experience or are likely to experience disability to achieve and maintain optimal functioning in interaction with their environments”,[4] then rehabilitation is a "set of interventions designed to optimise functioning in individuals with health conditions in interaction with their environment". In effect, rehabilitation is composed of multiple components or "interventions" to address issues related to all domains of the World Health Organization's International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). These include body functions and structures, capacity for activities, the performance of activities, participation, environmental/contextual factors, and personal factors.[5]

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)[edit | edit source]

In 2001, the fifty-fourth World Assembly officially approved the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as a replacement for the International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps (ICIDH).[6] The ICF is a classification of health and health-related domains. It focuses on human functioning, from "proper function" to "major disability", in relation to a person’s activities and participation, which are influenced by environmental factors, health conditions, and personal factors.

Unique Features of the ICF:[7]

- Includes social and environmental aspects of disability and health.

- Allows for the identification of factors at both individual and system levels.

- Provides a framework for mental and physical disorders.

- Allows for organisation and communication of information on human functioning.

- Facilitates interdisciplinary and inter-professional practice by providing specificity and a common language in the world of functioning and disability.

- Allows for an interactive relationship between health conditions, impairments, functional limitation/activity restrictions and environmental and personal factors.

- In this model, the relationship is not linear, but one component influences and is influenced by other factors.

- Data collection allows the user to determine the associations and causal links between different components.

The ICF is a biopsychosocial model of functioning, health and disability. The primary purpose of applying the ICF in clinical practice is to establish a common language for defining health and health-related states between providers.[8] It can enhance decision-making among healthcare and social care professionals. The ICF's holistic approach helps clinicians make more informed assessments, develop more effective interventions, and achieve good patient outcomes. By using a standard language to define and measure disability, the ICF helps to explain how a person's body problems and social circumstances affect their functioning within their environment.[9]

In the ICF model, a person is viewed in terms of their health conditions, body functions and structures, activities and participation, and environmental and personal factors. [10]

- Health Condition: "an umbrella term for the disease, disorder, injury, trauma".[8]

- Body Functions: "physiological functions of the body system, including psychological functions".[11] Examples:

- mental functions

- sensory functions and pain

- voice and speech functions

- functions of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems

- functions of the skin and related functions

- Body Structures: "anatomical parts of the body, such as organ, limbs and their components".[11] Examples:

- structure of the nervous system

- structure related to movement (e.g. weight-bearing limitations following surgery or trauma)

- structures involved in voice and speech

- Activity: "execution of a task or action by an individual".[11] Activity limitations describe the problems or issues at the level of the individual. Examples:

- learning and applying knowledge

- general tasks and demands

- communication

- mobility

- Participation: "involvement in a life situation".[11] Participation restrictions are problems the individual may experience in their life situation or within an environmental context.

- Environmental Factors: the "physical, social and attitudinal environment in which people live".[11] Environmental factors can be considered a barrier or facilitation in terms of how they affect an individual's functioning.[7] Examples:

- products and technology

- the natural environment and human-made changes to the environment (e.g. the accessibility of a building for a wheelchair user)

- support and relationship

- Personal Factors: the "particular background of an individual's life and living".[11]

You can find a complete list of the key components of the ICF model here.

As mentioned above, health conditions refer to disease (acute or chronic), injury or trauma - they may also include other circumstances such as genetic predisposition, stress, pregnancy or ageing. Anyone with a health condition who experiences some form of limitation in body functions and structures, such as cognition, emotion, vision, communication, motor function and mobility, may need access to rehabilitation. As such, rehabilitation interventions should be guided by the ICF and incorporate techniques that allow for the assessment and identification of problems in all areas of the ICF. This should be followed by the selection of interventions that address impairments in body functions and structures, activity limitations and participation restrictions and consider both personal and environmental contextual factors that impact functioning.

Most individuals participating in rehabilitation require techniques and interventions addressing one, many or all of the components of the ICF that contribute to reduced functioning. The overriding goal of rehabilitation is to utilise appropriate techniques and interventions that allow the individual to optimise their function.[5] Given this, individuals with health conditions or injuries may require rehabilitation at various points across their lifespan.

The timing and type of intervention that a rehabilitation provider selects depend greatly on several factors, which include:

- the aetiology and severity of the person’s health condition

- the prognosis

- how the person’s condition affects their ability to function in their environment

- the individual’s identified personal goals and what the person wants to achieve from the rehabilitation process

Clinical Assessment[edit | edit source]

Assessment, typically the first step in the rehabilitation process and arguably one of the most important elements, has always been a key part of the rehabilitation process. It has been viewed as a critical element in enhancing rehabilitation outcomes. Rehabilitation interventions are only as good as the assessment on which they are based. The clinical assessment provides information to guide our decision-making in formulating goals and selecting appropriate rehabilitation interventions. As such, our assessment and choice of rehabilitation techniques underpin much of what we do within rehabilitation.

Assessment has many meanings, even within the local rehabilitation context. It can involve one or many professions, and it is always followed by action.[12] It effectively encompasses collecting and evaluating patient data to guide the development of patient-centred goals.

The definition of assessment includes "techniques and procedures for classification or measurement of a variable pertaining to the complete person".[13]

The following are examples of classification:

- injury type assignment, e.g. Athletics Muscle Injury Classification[14]

- assignment to a certain diagnostic class[13]

- assignment based on the type of facility where services are received (inpatient, outpatient, homecare)[13]

Examples of person variables include:[13]

- balance

- muscle strength

- range of motion

- pain level

- endurance

- bladder / bowel continence

Rehabilitation is a problem-solving process. The first stage in any problem-solving process is to understand the problem in detail:

- what is the fundamental difficulty, which may or may not be the same as the initially identified problem;

- what are the critical factors related to the problem;

- what factors, if any, might help identify measures that could improve the situation; and

- what factors help decide which activities should be undertaken and/or should not be undertaken?

While the clinical assessment forms the initial foundation for the rehabilitation process, it is also an ongoing and continuous process. It should occur throughout the rehabilitation process to monitor for changes in the patient and guide modification of the rehabilitation plan. As such, the rehabilitation professional needs to know what assessment techniques and tools are available, how and when to use them, how to choose the best one, how to interpret the data they provide, and equally importantly, they also need to know when not to use them.

Selection of Rehabilitation Techniques and Interventions[edit | edit source]

Rehabilitation is a highly diverse field that uses many interventions to facilitate functional change.[15] A patient-centred approach in rehabilitation is characterised by the following:

- including patients in decisions such as goal identification and agreement

- respecting patients' values and preferences

- focusing on outcomes that improve a patient's quality of life

As a result, patients are engaged, confident, motivated and satisfied with the rehabilitation.

An effective, efficient, and patient-centred rehabilitation intervention "requires a system for specifying treatments that describes specific clinician actions in rehabilitation and links them to the desired functional changes in a structured, meaningful way."[16]

Complex interventions in rehabilitation include several components. According to the Medical Research Council, examples of complex interventions include:[17]

- home care services or rehabilitation services at a Stroke Unit in a hospital

- community intervention: prevention or promotion (e.g. prevention of heart disease)

- group-based intervention: MyBack program, smoking cessation programmes

- interventions directed at individual patients: health/nutrition promotion to fight obesity

The Medical Research Council[18] has published guidance on research related to developing, evaluating, and implementing complex interventions to improve health. It recommends considering key questions when developing a rehabilitation intervention, particularly in the case of complex healthcare.

The Medical Research Council's guidance was intended mostly to help researchers choose appropriate methods within research and research funders to understand the constraints on evaluation design. However, the first four questions (listed below) are also applicable and relevant to service managers and rehabilitation professionals to guide their selection of appropriate rehabilitation techniques and interventions.[18]

- Are you clear about what you are trying to do, what outcome you are aiming for, and how you will bring about change?

- This is applicable whether we are researching the impacts of an intervention or selecting a technique or intervention for use in our daily clinical practice as rehabilitation professionals. When considering what rehabilitation techniques and interventions to use, the patient's wants and needs are key. Their rehabilitation goals should be central to what we are trying to achieve when selecting our intervention. Providing patient-centred care that incorporates a patient's cultural considerations, needs, and values is a necessary skill for best practice services.[19][20]

- Does your intervention have a coherent theoretical basis that has been used to develop the intervention?

- Evidence-based practice is "the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient's values with consideration for all circumstances related to patient assessment and management, practice management, and health policy decisions on making".[21] Rehabilitation professionals recognise the use of evidence-based practice as central to providing high-quality care and decreasing unwarranted variation in practice. The rehabilitation professional's knowledge and skills are key to this evidence-based process. The personal scope of practice consists of techniques and interventions undertaken by them that are situated within their unique body of knowledge where the individual is educated, trained, and competent to perform that activity. The use of clinical decision-making and judgment is key.[22] Since the implementation of evidence-based practice in rehabilitation, there have been major advances in the quality of health care and patient outcomes.

- Can you describe the technique or intervention fully so that it can be implemented properly for the purposes of your evaluation and replicated by others?

- This is particularly vital in research to ensure that studies can be replicated or further developed within clinical practice. However, it is also important as it enables other rehabilitation professionals working with a person to understand the rehabilitation techniques and interventions being used. Moreover, if a person's rehabilitation is being transferred to another team member, this clinician will be able to evaluate and continue to provide and build on effective rehabilitation interventions.[18]

- Does the existing evidence suggest that it is likely to be effective or cost-effective?

- Ensuring we choose rehabilitation techniques or interventions that are both effective and cost-effective can be very important, particularly when selecting and developing techniques or interventions for use within low-resource settings. We know in many cases, there is often more than one technique or intervention that can support a specific goal. Therefore, as clinicians, we need to be able to weigh up the technique or intervention options available. We must consider the effectiveness of the technique or intervention to optimise the function of the individual but also the cost implications of this intervention, both for the individual (particularly where the individual has to cover the cost of the intervention) and/or the rehabilitation service.[18]

Another attempt to formulate guidelines for selecting rehabilitation interventions is the Ottawa Methods Group (OMG).[23] The OMG has invited clinical specialists who formed the Philadelphia Panel to develop evidence-based clinical practice guidelines to select rehabilitation interventions for a specific condition, including the management of low back, knee, neck, and shoulder pain. The following are the criteria presented by the Panel:[24]

- presence of evidence of clinically important benefit in patient-important outcomes (i.e. improvement of 15% or more relative to control)

- outcome measurements must demonstrate validity and reliability

- outcomes of primary clinical importance include pain, functional status, patient global assessment, quality of life (QOL), return to work, and patient satisfaction

The Ottawa Methods Group also created guidelines for rehabilitation interventions to manage adult patients with hemiplegia or hemiparesis due to cerebrovascular accidents.[25]

Summary[edit | edit source]

When choosing rehabilitation techniques and interventions, healthcare practitioners must consider the following:

- Benefits delivered in patient-important outcomes

- Cost-effectiveness

- Feasibility of the implementation of the intervention into practice

- Stability of the intervention

- Presence of adverse effects

Resources[edit | edit source]

- International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF)

- Rehabilitation 2030

- Rehabilitation Matters

References [edit | edit source]

- ↑ Ginis KA, van der Ploeg HP, Foster C, Lai B, McBride CB, Ng K, Pratt M, Shirazipour CH, Smith B, Vásquez PM, Heath GW. Participation of people living with disabilities in physical activity: a global perspective. The Lancet. 2021 Jul 31;398(10298):443-55.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Cieza A, Causey K, Kamenov K, Hanson SW, Chatterji S, Vos T. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2021 Dec 19;396(10267):2006-2017.

- ↑ Duttine A, Battello J, Beaujolais A, Hailemariam M, Mac-Seing M, Mukangwije P, et al. Introduction to Rehabilitation Factsheet. Handicap International. 2016. Available from: https://humanity-inclusion.org.uk/sn_uploads/document/2017-02-factsheet-rehabilitation-introduction-web_1.pdf [Accessed on 8 January 2020].

- ↑ World Health Organization. Rehabilitation: key for health in the 21st century. InBackground paper prepared for the meeting rehabilitation 2017 (Vol. 2030). Available from https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/health-topics/rehabilitation/call-for-action/keyforhealth21stcentury.pdf?sfvrsn=43cebb7_5 [last access 5.05.2023]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 World Health Organization. World Report on Disability 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. Rehabilitation.

- ↑ Leonardi M, Lee H, Kostanjsek N, Fornari A, Raggi A, Martinuzzi A, Yáñez M, Almborg AH, Fresk M, Besstrashnova Y, Shoshmin A, Castro SS, Cordeiro ES, Cuenot M, Haas C, Maart S, Maribo T, Miller J, Mukaino M, Snyman S, Trinks U, Anttila H, Paltamaa J, Saleeby P, Frattura L, Madden R, Sykes C, Gool CHV, Hrkal J, Zvolský M, Sládková P, Vikdal M, Harðardóttir GA, Foubert J, Jakob R, Coenen M, Kraus de Camargo O. 20 Years of ICF-International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: Uses and Applications around the World. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Sep 8;19(18):11321.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Saleeby P. Introduction to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) Course. Plus 2022.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Aims of the ICF. Available from https://www.icf-elearning.com/wp-content/uploads/ [last access 16.05.2023]

- ↑ Pretis M, Kopp-Sixt S, Er-Sabuncouglu M, Todorova K, Grüner C, Kaiser L, Patterer I, Labudovikj RP. ICF as a Problem Solving Tool in Transdisciplinary Teams. Advanced Research in Psychology. 2020 Jul 29:14132.

- ↑ Saleeby P. ICF and Application in Clinical Practice Course. Plus 2022

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 The ICF model. Available from https://www.icf-elearning.com/wp-content/uploads/articulate_uploads/ [last access 16.05.2023]

- ↑ Wade DT. Evidence relating to assessment in rehabilitation. Clinical Rehabilitation. 1998 Jun;12(3):183-6.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Tesio LU. Functional assessment in rehabilitative medicine: principles and methods. Europa medicophysica. 2007 Dec 1;43(4):515.

- ↑ Macdonald B, McAleer S, Kelly S, Chakraverty R, Johnston M, Pollock N. Hamstring rehabilitation in elite track and field athletes: applying the British Athletics Muscle Injury Classification in clinical practice. Br J Sports Med. 2019 Dec;53(23):1464-1473.

- ↑ Whyte J, Dijkers MP, Fasoli SE, Ferraro M, Katz LW, Norton S, Parent E, Pinto SM, Sisto SA, Van Stan JH, Wengerd L. Recommendations for reporting on rehabilitation interventions. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2021 Jan 1;100(1):5-16.

- ↑ Jette AM. Opening the black box of rehabilitation interventions. Physical Therapy. 2020 Jun 23;100(6):883-4.

- ↑ Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, Kinmonth AL, Sandercock P, Spiegelhalter D, Tyrer P. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ. 2000 Sep 16;321(7262):694-6.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Baird J, Unit ML, Petticrew M, White M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions. Swindon, UK: Medical Research Council. 2006.

- ↑ WHO (World Health Organization). 2001. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva: WHO

- ↑ Thomas EC, Bass SB, Siminoff LA. Beyond rationality: Expanding the practice of shared decision making in modern medicine. Social Science & Medicine. 2021 May 1;277:113900.

- ↑ Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM, Haynes RB, Richardson WS: Evidence-based medicine: what it is and isn’t. BMJ 1996;312:71-2

- ↑ WHO (World Health Organization). 2001. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva: WHO

- ↑ Ottawa panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for therapeutic exercises and manual therapy in the management of osteoarthritis. Phys Ther. 2005 Sep;85(9):907-71.

- ↑ Philadelphia Panel Members, Clinical Specialty Experts, Albright J, Allman R, Bonfiglio RP, Conill A, Dobkin B, Guccione AA, Hasson S, Russo R, Shekelle P. Philadelphia Panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on selected rehabilitation interventions: overview and methodology. Physical Therapy. 2001 Oct 1;81(10):1629-40.

- ↑ Ottawa Panel; Khadilkar A, Phillips K, Jean N, Lamothe C, Milne S, Sarnecka J. Ottawa panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for post-stroke rehabilitation. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2006 Spring;13(2):1-269.