Introduction to Frailty

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Frailty is a clinical state that is associated with an increased risk of falls, harm events, institutionalisation, care needs and disability/death.[1]

- Frailty affects quality of life

- It is becoming more common with ageing populations[1]

- The prevalence of frailty ranges from 4-59% in community-dwelling older adults, with higher rates in women[2]

- It is estimated that 25% to 50% of individuals aged over 85 years are frail[3]

- The prevalence of frailty in a population is associated with the prevalence of other chronic conditions, such as depression, nutritional status, socio-economic background and level of education[2]

"Because of its powerful association with adverse events (i.e. disability, mortality, and hospitalization) and its high prevalence in older adults, frailty has been placed in the geriatric medicine spotlight"[4]

However, while it is generally accepted that frailty exists, it remains difficult to define as it manifests differently in each individual. A working definition of frailty is as follows:

- Frailty is a distinct clinical entity from ageing, but it is related to the ageing process. It consists of multi-system dysregulation leading to a loss of physiological reserve. This loss of reserve means that the individual living with frailty is in a state of increased vulnerability to stressors meaning they are more likely to suffer adverse effects from treatments, diseases or infections.[1]

Morley et al.[5] (2013) provide the following definition:

“Frailty is a clinical state in which there is an increase in an individual’s vulnerability for developing increased dependency and/or mortality when exposed to a stressor.”[5]

There are two key concepts that can be taken from these definitions:[1]

- Frailty is separate from, but related to ageing. While older people tend to be more frail, you will not be frail just because you are old. Frailty depends on your physiological state and how well you can respond to stressors (injury/illness).[1][6]

- Frailty involves multiple systems rather than just a single body system. Frail individuals will usually have a number of co-morbidities (eg cardiovascular, musculoskeletal and neurological).[1]

Frailty is a dynamic state. Frailty is "associated with a prodromal stage called pre-frailty, a potentially reversible condition before onset of established frailty."[7] There is also evidence that, once established, frailty is also modifiable and can be reversed more easily than disability.[8] This is significant as it means that an individual's frailty level can be influenced by our interventions.[1]

Overall, if unmanaged, a frail individual will follow a trajectory towards disability and death.[1][8][9]

Models of Frailty[edit | edit source]

There are two main theories that underpin the concept of frailty:

- Fried's Phenotype Model

- Rockwood's Accumulation of Deficits Model.

It is important to understand that these are not competing models. They should be considered as complementary - both have been validated and have been used to develop various assessment tools and treatment indicators.

Fried's Phenotype Model[edit | edit source]

Fried's Phenotype Model was first published in 2001.[10] It is a yes-no model based on five subcategories. Each subcategory is scored as 0 (no) or 1 (yes). It assumes an individual is frail if s/he has a score of greater than three.[1] The five categories are:[1][11]

- Physical inactivity

- Low muscle strength - can be measured in grip strength - <21 kgf in men and <14 kg in women (NB this is dependent on ethnicity)

- Slow gait speed - less than 0.8 m/s with or without a walking aid

- Exhaustion/ fatigue - this is self-reported

- Weight loss - loss of 10 lbs/4.5 kg or more in 1 year

The scoring is as follows:

- 0-1 = not frail

- 1-2 = pre-frail

- 3+ = frail (mild, moderate and severe)

When using this model, it is important to remember that frailty is a multi-system dysregulation.[1][12]

In frailty, "it's not just one body system that's a problem. So it normally means that you have a lengthy list of comorbidities involving different organ systems, different body systems, and that could be as broad as cardiovascular co-morbidities, as well as musculoskeletal co-morbidities, as well as neurological co-morbidities."[1] -- Scott Buxton

Therefore, when considering Fried's Phenotype Model, please consider the following:

- If an impairment is clearly due to a mono-articular or single system problem (e.g. low grip strength following a hand injury), then this must be considered when assessing for frailty.

- This model focuses solely on physical attributes of frailty.

- Some researchers, therefore, consider that Fried's Phenotype Model is an incomplete model as it does not address cognitive aspects or chronic conditions which are associated with frailty.[13] However, this focus on physical attributes makes Fried's Model useful for physiotherapists as it provides clear direction when creating treatment plans to address frailty. For example, if a patient is shown to have low muscle strength, treatment would focus on strengthening; patients who are found to be physically inactive would need to increase their activity levels.[1]

Rockwood's Accumulation of Deficits Model[edit | edit source]

The Rockwood Model considers how frailty can be the result of an accumulation of various deficits.[14] Not all adults develop the same number of deficits. Thus, some become frail whereas others do not.[15]

"Frailty was introduced to explain why people of the same age have varying degrees of risk. The deficit accumulation approach shows that as people age, they accumulate health deficits, and that more deficits confer greater risk. Frailty results because not everyone of the same age has the same number of deficits."[15] -- Kenneth Rockford (2016)

This accumulation of deficits can be quantified using the Frailty Index.

- In this index, 92 parameters of symptoms, signs, abnormal laboratory results, disease states and disabilities - ie deficits - were used to define frailty.[3]

- The number of parameters has subsequently been reduced to around 30 variables.[3]

- An individual's Frailty Index score indicates how many deficits are present - the more deficits, the greater the chance s/he is frail.[14]

- The Frailty Index score is calculated by dividing the total number of impairments by the total number of parameters examined. An individual is considered more frail the closer their overall score is towards 1.0.

Several studies have found that the Frailty Index score is strongly related to the risk of death and institutionalisation.[3] It is, therefore, considered a useful model for primary care (GPs or Geriatricians), but given it can be time-consuming to complete, additional measures have been developed that are quicker to use including:

- The electronic Frailty Index (eFI), which was developed by Clegg and colleagues in 2016.[16] It identifies frailty using data that is held on primary care databases. It categorises patients into four categories based on this data: fit older individuals, as well as individuals with mild frailty, moderate frailty and severe frailty.[16]

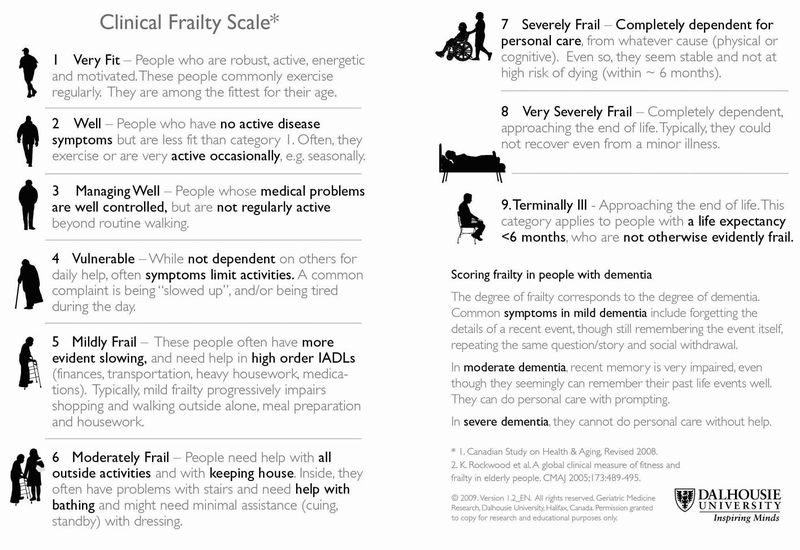

- The Clinical Frailty Scale (see image below), is a straightforward and accessible nine-category tool that can be used to quickly and simply assess frailty. It has been validated in adults aged over 65 years.[17][18] It is important to note that it is "not widely validated in younger people or those with stable single-system disabilities."[19] The clinician judges a patient's level of frailty based on specific clinical findings, including physical disability, cognition and co-morbidity.[20]

- A score from 1 (very fit) to 9 (terminally ill) is given based on the descriptions and pictographs of activity and functional status.[21]

- Particular attention should be paid to those who score 5 or more as this is the marker for requiring a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) and often referral to geriatric or frailty specialists,

- A 2017 Cochrane review found that older people are more likely to be alive and in their own homes at follow-up if they received a CGA on admission to hospital.[22]

Summary[edit | edit source]

- Frailty is a clinical state involving multiple systems that is related to ageing.

- Frailty can ultimately lead to disability and death, but it is not a fixed state and can be positively affected if appropriate interventions are provided.

- Two key models underpin the concept of frailty: Fried's Phenotype Model and Rockwood's Accumulation of Deficits Model. Fried’s Model focusses solely on the physical aspects of frailty whereas Rockwood's Model considers how health deficits accumulate, which increases the likelihood an individual will be frail.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 Buxton S. An Introduction to Frailty course. Plus. 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Rohrmann S. Epidemiology of frailty in older people. In: Veronese N. (editor). Frailty and Cardiovascular Diseases . Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, vol 1216. Springer, Cham, 2020.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in older people, The Lancet. 2013; 381(9868): 752-62. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4098658/

- ↑ Álvarez-Bustos A, Carnicero-Carreño JA, Sanchez-Sanchez JL, Garcia-Garcia FJ, Alonso-Bouzón C, Rodríguez-Mañas L. Associations between frailty trajectories and frailty status and adverse outcomes in community-dwelling older adults. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022 Feb;13(1):230-9.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Morley JE, Vellas B, Abellan van Kan G, Anker SD, Bauer JM, Bernabel R et al. Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013. 14(6): 392-7.

- ↑ Verghese J, Ayers E, Sathyan S, Lipton RB, Milman S, Barzilai N, Wang C. Trajectories of frailty in aging: Prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2021 Jul 12;16(7):e0253976.

- ↑ Sezgin D, Liew A, O'Donovan MR, O'Caoimh R. Pre-frailty as a multi-dimensional construct: A systematic review of definitions in the scientific literature. Geriatr Nurs. 2020 Mar-Apr;41(2):139-46.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Clegg A, Bates C, Young J, Ryan R, Nichols L, Teale EA et al. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age and Ageing. 2016; 45(3): 353–60, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw039.

- ↑ Álvarez-Bustos A, Carnicero-Carreño JA, Sanchez-Sanchez JL, Garcia-Garcia FJ, Alonso-Bouzón C, Rodríguez-Mañas L. Associations between frailty trajectories and frailty status and adverse outcomes in community-dwelling older adults. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022 Feb;13(1):230-9.

- ↑ Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol. 2001. 56A(3): 146-56.

- ↑ Pogam ML, Seematter-Bagnoud L, Niemi T, Assouline D, Gross N, Trächsel B, et al. Development and validation of a knowledge-based score to predict Fried's frailty phenotype across multiple settings using one-year hospital discharge data: The electronic frailty score. EClinicalMedicine. 2022 Jan 10;44:101260.

- ↑ Picca A, Calvani R, Marzetti E. Multisystem derangements in frailty and sarcopenia: a source for biomarker discovery. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2022 May 1;25(3):173-7.

- ↑ Fried LP, Xue QL, Cappola AR, Ferrucci L, Chanves P, Varadhan R, Guralnik JM, Leng SX, Semba RD, et al. Nonlinear multisystem physiological dysregulation associated with frailty in older women: implications for etiology and treatment. J Gerontol. 2009. 64(10): 1049-57.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Rockwood, K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in Relation to the Accumulation of Deficits. The Journals of Gerontology Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2007; 62(7): 722-7. Available from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6204727_Frailty_in_Relation_to_the_Accumulation_of_Deficits

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Rockwood K. Conceptual Models of Frailty: Accumulation of Deficits. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(9):1046‐1050.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Lansbury LN, Roberts HC, Clift E, Herklots A, Robinson N, Sayer AA. Use of the electronic Frailty Index to identify vulnerable patients: a pilot study in primary care. British Journal of General Practice. 2017; 67 (664): e751-e756.

- ↑ Acute Frailty Network. Clinical Frailty Scale. Available from https://www.acutefrailtynetwork.org.uk/Clinical-Frailty-Scale (accessed 12 June 2020).

- ↑ Sablerolles RSG, Lafeber M, van Kempen JAL, van de Loo BPA, Boersma E, Rietdijk WJR, et al. Association between Clinical Frailty Scale score and hospital mortality in adult patients with COVID-19 (COMET): an international, multicentre, retrospective, observational cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021 Mar;2(3):e163-e170.

- ↑ Rockwood K, Theou O. Using the Clinical Frailty Scale in allocating scarce health care resources. Can Geriatr J. 2020 Sep 1;23(3):210-5.

- ↑ Broad A, Carter B, Mckelvie S, Hewitt J. The convergent validity of the electronic Frailty Index (eFI) with the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS). Geriatrics (Basel). 2020 Nov 9;5(4):88.

- ↑ Juma S, Taabazuing MM, Montero-Odasso M. Clinical frailty scale in an acute medicine unit: a simple tool that predicts length of stay. Can Geriatr J. 2016; 19(2): 34-9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/P

- ↑ Ellis G, Gardner M, Tsiachristas A, Langhorne P, Burke O, Harwood RH, Conroy SP, Kircher T, Somme D, Saltvedt I, Wald H. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017(9). Available from: https://www.cochrane.org/CD006211/EPOC_comprehensive-geriatric-assessment-older-adults-admitted-hospital (last accessed 4.5.2019)