Discharge management of the amputee

Original Editor - Islem Cheriet and Ahmad Abdal Qader Hasan Al-Mosa

Top Contributors - Sheik Abdul Khadir, Admin, Kim Jackson, 127.0.0.1, Tony Lowe, Tarina van der Stockt, Simisola Ajeyalemi and Karen Wilson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Successful rehabilitation post-amputation relies on the patient’s achievement of goals that were pre-determined by a inter/multidisciplinary team and assessed through specific Outcome Measures for Patients with Lower Limb Amputations. Successful rehabilitation is therefore intrinsically linked to effective discharge, which allows a patient to function optimally in his/her environment with the necessary tools for proper management and self-care at home, inherent to the quality of life and empowerment of the patient. Because one can expect prosthetic usage to be altered or health status to change over time, timely re-evaluation of the aforementioned outcome measures should be performed.[1]

However, there is currently no clear evidence in the literature supporting the optimal process for patients’ discharge following an amputation, or suggesting determinants for the management of patients post-discharge to maintain their independence through regular follow-up.

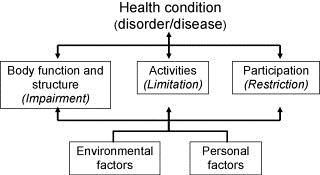

Discharge Determinants: WHO ICF Model[edit | edit source]

The patients’ expected level of functional independence will not only be influenced by their physical and psychological presentation, but by their social environment as well.[2]

In fact, the WHO developed an international standard used to describe and measure health and function: the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, commonly known as the ICF (International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)). Instead of focusing on a patient’s diagnosis or disability, the ICF encourages health care professionals to adopt a holistic approach through a biopsychosocial model that considers all aspects present in someone’s life (health condition, environmental and personal factors) as interacting bodies that are determinant to the three level of functioning (body structure and functions, activity, and participation).

In accordance with the ICF model, Rommers et al. describe how “parameters such as physical condition, social factors, age and co-morbidity are influencing factors in determining the discharge destination” [3]. It is indeed by considering the patients’ activity and participation that the health care team can effectively direct patients towards the gradual resumption of roles within a community, whether it is practising a sport or returning to work.

Prior to discharge, occupational and physical therapists also need to conduct a detailed interview with the patients pertaining to environmental factors. For instance, positively reinforcing the importance of the patients’ social network reintegration is paramount to their recovery and should not be overlooked by the rehabilitation team [4] Together with the patient and his family, the rehabilitation team also determines the need for modifications around their home, alterations of activities of daily living, or relocation to a residence that provides assistance. Indeed, functional outcomes in amputees has been shown to be improved by modification of their physical environment [5].

Personal factors such as coping mechanisms in the face of bereavement or overall behavioural patterns equally need to be taken into consideration to ensure the well-being of patients during and following the maintenance phase once they are at home.

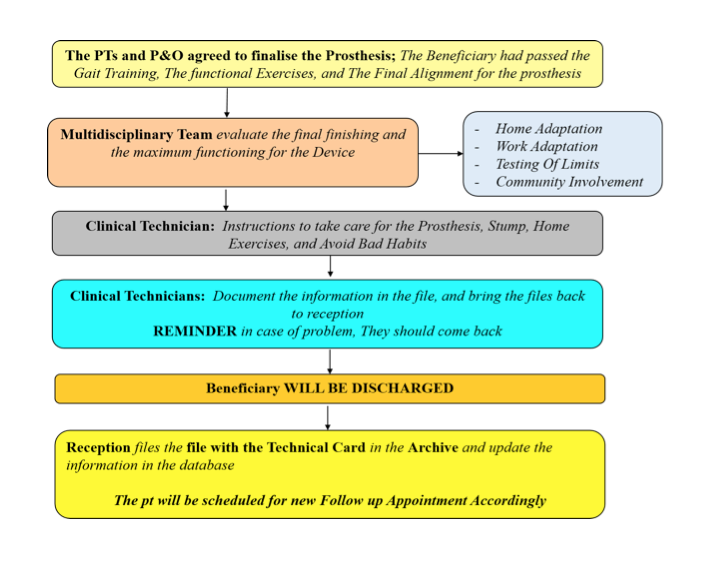

The chart below illustrates an example of a holistic standard procedure that was developed with the support of the ICRC towards best practice at the National Authority for Prosthetics and Orthotics (NAPO) in Khartoum, Sudan. It describes the overall process following rehabilitation and proper fitting, which includes a thorough assessment and home/work adaptation, instructions for self-care and management at home, final discharge and follow up. The role of the multidisciplinary team is to collaborate and work with the beneficiary towards optimal quality of life, while ensuring that all information is documented in the patient’s chart.

Self-care and Management[edit | edit source]

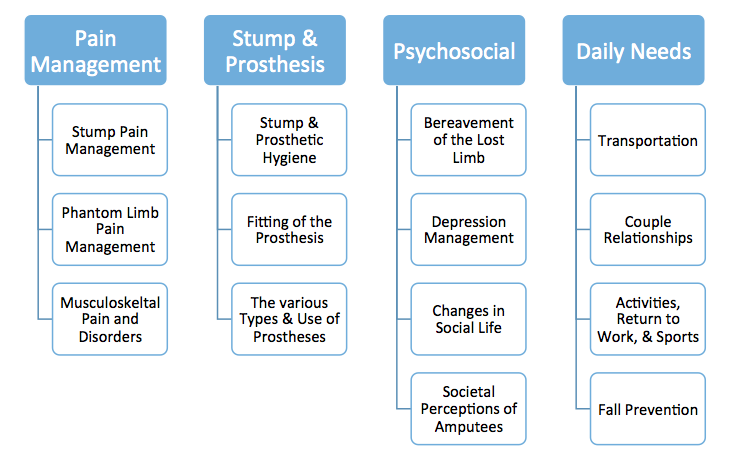

Throughout the rehabilitative process, health care professionals help patients acquire the skills and tools needed to adapt to their life after amputation, through therapeutic education [6]. Pantera et al. (2014) reviewed the literature and analyzed experts opinion when looking at therapeutic education for persons after an amputation. Themes that were deemed important include[6]:

Themes that will be covered in this article pertain to physical activity and diet, stump and prosthetic hygiene, when to contact the medical team, as well as effective follow up of patients.

Lifestyle and Habits[edit | edit source]

Amputation is a major cause of permanent disability, and it may alter the free time activities of an individual because of anxiety, depression, and isolation. Evidence is showing that physical activity can indeed prevent and treat diseases and has many added benefits for persons who face physical or psychological challenges, as advocated by the World Health Organization. [4]

The physiotherapist should provide an exercise plan with clear mentions of activity restrictions if any, and ways to prevent complications such as contractures or decreased blood flow to the stump. The patient can resume his/her activities of daily living as indicated by the health care professionals, and should be encouraged to do as much as possible. This will empower the individual and improve the trust in his/her capabilities with the new prosthesis.

Healthy habits can be advocated for at that time. Dietary recommendations are all the more crucial when planning for the discharge of diabetic patients. Health care professionals need to sensitise them as to closely control their blood sugar levels, prevent sores and infections through careful skin examination and adequate shoe wear.

Stump and Prosthetic Hygiene[edit | edit source]

It is important that patients take good care of their stump and prosthesis, to avoid complications such as infection at the wound site, bedsores, pain due to improper alignment, or muscle contractures. It is important to:

- Depending on the healing stage of the wound and the doctor’s indications, keep the wound clean and dry OR wash the stump daily once the dressings have been removed, and dry it well

- Clean the area around the wound gently with mild soap and water

- Inspect the stump daily, looking for any red areas or dirt

- Wrap the stump every 2 to 4 hours with the elastic bandage, as shown by the health care team

- Wear shoes that are similar to the ones they usually wear to avoid changes in body alignment and consequent changes in pressure points in the prosthesis

- Examining the prosthesis regularly for loose parts of damaged areas

- Wear clean dry socks with the prosthesis

- Clean the prosthesis’ socket with soap and water

- Maintain a stable body weight for the optimal fitting of the prosthesis

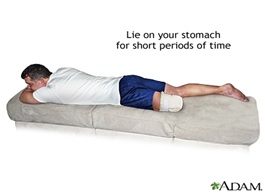

- For below the knee amputations, lie on the stomach 3-4 times a day for 20 minutes to stretch the hip muscles.

When to contact the medical team[edit | edit source]

Following discharge, patients should be confident as to when it is a good idea to contact the medical team or doctor. Some points are:

- A stump that looks more red

- The skin around the stump feels warmer

- There is swelling, bulging, or bleeding around the wound

- A foul smell is coming from the wound

- Other signs and symptoms of infection such as fever or chills

- Pain that is not well controlled with the prescribed medication

- Side effects from the medication such as dizziness, nausea, hallucinations

- If the patient has any additional question concerning the amputation or stump care

Social Inclusion[edit | edit source]

Achieving social inclusion is a real challenge that will depend on many factors. We usually define 3 levels of inclusion that would permit amputee full participation in the community. Home and private environment; work and school places; society and public environment. Specific advice and support could be given for each level and the success of the inclusion (wellbeing of the persons and feeling of respect, self-esteem) will depend on the combination of these 3 levels of human interaction.

Family/caregivers role & support[edit | edit source]

The presence and participation of the family/caregivers with the amputee all along the rehabilitation process is very important. The challenge to overcome the new situation is a challenge for both, the amputee and his family/caregivers. During the discharge and return at home, a suitable preparation and a good understanding of what could be the role of each other is determinant for the success of this challenging step. Training and advice should, therefore, be addressed in that sense, promoting discussion and self-thinking with family and caregiver in their new role.

The therapeutic team should as well train the family/caregivers on technical issues to be able to assist their family member if necessary (bandage, transfers, prevention) without anxiety. It is very important to associate family/caregivers in all exercises and home programs in order to facilitate the interaction between family members.

Amputee’s family/caregiver, may also be experiencing their own sense of loss, and may have trouble coping with the changes in their own lifestyle. This is normal and mainly due to stress and the added responsibilities of caring for their family member. Amputee’s education and psychological support should always include a section about family inclusion and the good attitude toward other family members.

Return to Work and activities[edit | edit source]

A review of the literature by Burger and Marincek [7] highlighted a recurring rate of 66% for return to work, with between 22 to 67% of subjects who maintained the same occupation and the remainder who had to change occupation.

From the different studies, return to work depends on:

| Factors influencing return to work | Description |

| General Factors |

|

| Factors related to disabilities linked to the amputation |

|

| Factors related to the work |

|

As a return to work is one of the main goals and a measure of rehabilitation [9] [10],team members should implement effective vocational rehabilitation and counselling for patients to guide them through the hardships of social reinsertion. Joint work and cooperation between the rehabilitation health care professionals, the company doctors, and the employers is, therefore, necessary towards optimal guidance of individuals [7].

Such vocational training is described by the "Vocational Rehabilitation Association of the UK" and illustrated in the diagram below. The team first conducts a thorough assessment (interests/job readiness/skills), sets realistic goals with patients, provides and promotes health advice, and guides them to adjust the medical and psychological impact of their disability via effective psychosocial interventions. Career counselling or job placement follows and can require further education or training. There is again assessment of the functional and work capacity of the patients, and further adjustments through the same cycle if need be.

The Amputee Clinic at the Ontario Workers’ Compensation Board in Canada is an example of centres that serve workers who have sustained an amputation as a result of a work related accident. It aims at assisting them with medical, prosthetic, psychosocial, and vocational services [8].

Children’s safe return to their activities and to school is also ensured through a similar assessment of the physical and psychosocial environment around those patients, and working with the parents for effective return to their daily life with their new prosthesis.

Social & sport activities[edit | edit source]

Participating in social activities and sport strengthens persons with mental and physical disabilities. It keeps them active, improves their general condition, balance and motor coordination and prevents further disablement. Social activities and sport also promote hopefulness, self-esteem, reintegration in social and professional life, solidarity between people and community awareness of disability issues. As they grow in self-confidence, later amputees may find themselves wanting to play an active role in their communities. Social activities and sport provide communities with opportunities to develop innovative and culturally acceptable approaches to disablement as well.

In amputee discharge management, the orientation of the amputee toward amputees groups and disabled sport association near their place of living is a necessity whatever the age and their level of independence.

Psychological Support[edit | edit source]

Grief and bereavement should be expected from patients in the face of the loss of a limb. The role of the physiotherapists is to actively listen to them and provide guidance towards appropriate psychological care and mental health counselling.

For instance, groups and associations exist to link amputees and their caregivers to other individuals living similar challenges. The video “Transformation” gives an inside look in people’s daily lives with a new prosthesis, as part of the Amputee Coalition’s efforts to bring people together so that they can support each other through their hardships.

Peer support groups could really help amputees to find their own way by sharing their experience. Amputees attending peer support groups report that having the occasion to discuss their situation with others experiencing similar challenges can provide valuable new perspectives, and a sense of belonging to a community for an issue that, on the contrary, often makes amputees feel isolated and excluded.

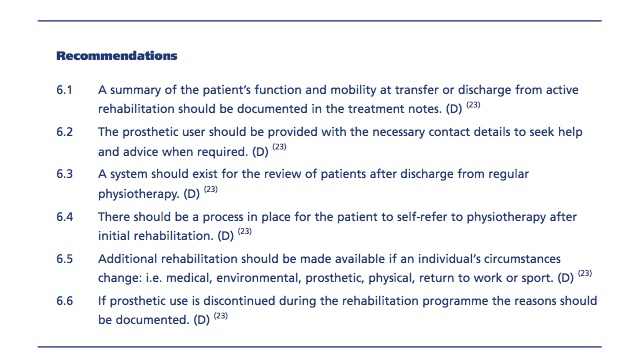

BACPAR Recommendations[edit | edit source]

The British Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Amputation Rehabilitation (BACPAR) published clinical guidelines for the management of amputees, including recommendations towards best practice for discharge and maintenance.[1]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Broomhead P, Clark K, Dawes D, Hale C, Lambert A, Quinlivan D, Randell T, Shepherd R, Withpetersen J. (2012) Evidence Based Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Lower Limb Prostheses, 2nd Edition. Chartered Society of Physiotherapy: London.

- ↑ Hanley, M. A., Jensen, M. P., Ehde, D. M., Hoffman, A. J., Patterson, D. R., & Robinson, L. R. (2004). Psychosocial predictors of long-term adjustment to lower-limb amputation and phantom limb pain. Disability&Rehabilitation, 26(14-15), 882-893.

- ↑ Rommers, G. M., Vos, L. D. W., Groothoff, J. W., Schuiling, C. H., &Eisma, W. H. (1997). Epidemiology of lower limb amputees in the north of The Netherlands: aetiology, discharge destination and prosthetic use. Prosthetics and orthotics international, 21(2), 92-99.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Deans, S. A., McFadyen, A. K., & Rowe, P. J. (2008). Physical activity and quality of life: A study of a lower-limb amputee population. Prosthetics and orthotics international, 32(2), 186-200.

- ↑ Collin, C., Wade, D. T., & Cochrane, G. M. (1992). Functional outcome of lower limb amputees with peripheral vascular disease. Clinical Rehabilitation, 6(1), 13-21.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Pantera, E., Pourtier-Piotte, C., Bensoussan, L., &Coudeyre, E. (2014). Patient education after amputation: Systematic review and experts’ opinions. Annals of physical and rehabilitation medicine, 57(3), 143-158.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Burger, H., &Marincek, C. (2007). Return to work after lower limb amputation. Disability & Rehabilitation, 29(17), 1323-1329.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Millstein, S., Bain, D., & Hunter, G. A. (1985). A review of employment patterns of industrial amputees-factors influencing rehabilitation. Prosthetics and orthotics international, 9(2), 69-78.

- ↑ Penn-Barwell, J. G. (2011). Outcomes in lower limb amputation following trauma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury-International Journal of the Care of the Injured, 42(12), 1474-1479.

- ↑ MacKenzie, E. J., Bosse, M. J., Castillo, R. C., Smith, D. G., Webb, L. X., Kellam, J. F., ... & McCarthy, M. L. (2004). Functional outcomes following trauma-related lower-extremity amputation. The Journal of Bone& Joint Surgery, 86(8), 1636-1645.

Additional Reading

World Health Organization (2004). A Manual for the Rehabilitation of People with Limb Amputation. United States Department of Defense. Moss Rehab Amputee Rehabilitation Program. Moss Rehab Hospital, USA.

Zidarov, D., Swaine, B., & Gauthier-Gagnon, C. (2009). Quality of life of persons with lower-limb amputation during rehabilitation and at 3-month follow-up. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 90(4), 634-645.

Hagberg, K. (2006). Transfemoral amputation, Quality of Life and Prosthetic Function. Studies focusing on individuals with amputation due to reasons other than peripheral vascular disease, with socket or osseointegrated prostheses. Department of Orthopaedics, Insitiute of Clincial Sciences, TheSahlgrenska Academy at Göteborg University, Sweden.