Diagnostic Imaging of the Lumbar Spine

Original Editor - Jigs Coligado

Top Contributors - Melissa Coetsee, Jigs Coligado, Kim Jackson and Lucinda hampton

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic imaging can be an important component of the assessment process. Imaging assists physiotherapists in screening for critical conditions and in defining musculoskeletal disorders. There has however been a major shift in guidelines on the way imaging is used in patients presenting with low back pain - in the past it was regarded as routine, but the evidence has challenged this practice.[1] Imaging of the lower back is now only recommended for a small percentage of patients, but despite this unnecessary imaging still persists in clinical practice.[1][2]

A general article on diagnostic imaging for Physical Therapist can be accessed in Physiopedia where MRI, X-rays, CT scans, and bone scans are discussed.

Imaging Used[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic ultrasound and X-rays are the most common forms of imaging requested by physiotherapists.[3] This page will cover the four diagnostic imaging modalities commonly used in lumbar spine disorders.

Radiograph (x-rays)[edit | edit source]

Considered as a first-line imaging modality for suspected disorders of musculoskeletal origin.[4] A general description can be accessed in a Physiopedia page about x-rays.

X-rays can evaluate lumbar alignment, vertebral body and disc space size, bone space and alignment, and gross evaluation of soft tissue structures. Clinically, x-rays are capable of detecting lumbar spine dislocations and fractures and can also be used to monitor fracture healing.[4]

Diagnostic Ultrasound[edit | edit source]

Ultrasound is a cross-sectional imaging method that uses sound waves reflected off tissue interfaces. It allows imaging of muscles while moving or applying resistance, as well as stress testing of ligaments. It is the quickest and least invasive examination of tissues close to the skin surface of the lumbar region, including cortical outline of lumbar vertebra, paralumbar muscles and tendons, spinal ligaments, intervertebral discs, and nerves.[5]

Clinically it is capable of detecting[5]:

- Tears of the paralumbar muscles, tendons, and ligaments

- Degenerative changes of tendons and paralumbar muscles

- Neuropathies of lumbar spinal nerves

- Inflammatory arthritis affecting the lumbar spine

- Cysts in the lumbar region

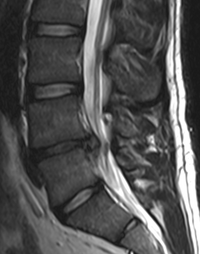

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)[edit | edit source]

MRI scans can help differentiate between traumatic, inflammatory, degenerative and neoplastic causes of lower back pain.[4] Tumours and cauda equina syndrome can also be evaluated through MR imaging. It is the best form of imaging to investigate soft tissue and neural structures of the spine. For a more in depth description see the page on MRI.

Clinical uses include detection of lumbar disc herniation, soft tissue injuries, lumbar vertebra pathology (including tumours) as well as stress fractures.[5]It is however not routinely indicated.

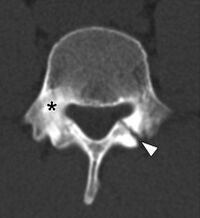

Computed Tomography[edit | edit source]

This modality can evaluate complex trauma and bony abnormalities of the lumbar region.[4] CT scan is described in a Physiopedia page. CT scans provide detailed, digital cross-sectional images of the body relatively free from the superimposition of the different tissues. Clinically the modality can detect fractures of the lumbar spine, especially complex fractures, arthritic changes of the lumbar vertebra, and lumbar spinal stenosis.[5]CT scans do however result in exposure to harmful radiation and should be used sparingly.

Caution with Imaging[edit | edit source]

Although advances in medical imaging have come with various benefits, the research has indicated that careful reasoning needs to be exercised when referring for imaging, and when interpreting and conveying results. Factors to consider include asymptomatic findings, iatrogenic effect and radiation exposure.

Asymptomatic Findings[edit | edit source]

Findings of degenerative changes in the spine are very common in asymptomatic individuals, especially with increasing age. It can therefore be concluded that many such findings may in fact be normal (not pathological) and may not be associated with pain. Even in symptomatic patients, degenerative findings do not always correlated with pain.

It is important to always consider the patient's clinical presentation, age and objective assessment when interpreting imaging results.[6]

| Image finding | Prevalence rates by age | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30y | 40y | 50y | 60y | 70y | 80y | |

| Disc degeneration | 52% | 68% | 80% | 88% | 93% | 96% |

| Disc height loss | 34% | 45% | 56% | 67% | 76% | 84% |

| Disc bulge | 40% | 50% | 60% | 69% | 77% | 84% |

| Disc protrusion | 31% | 33% | 36% | 38% | 40% | 43% |

| Annular fissure | 20% | 22% | 23% | 25% | 27% | 29% |

| Facet degneration | 9% | 18% | 32% | 50% | 69% | 83% |

| Spondylolisthesis | 5% | 8% | 14% | 23% | 35% | 50% |

A Systematic Review on Lumbar MRI results in adults younger that 50y, found the following[7]:

- In younger individuals (<50y) disc protrusion is more likely to be associated with symptoms, as the prevalence of disc protrusions in symptomatic individuals is higher (40%) than in asymptomatic individuals (20%).

- Disc extrusions are very rare in asymptomatic individuals

- There is a strong association between disc bulges/spondylolysis and low back pain in individuals younger than 50y - this association disappears with increasing age.

- Although associations exist between low back pain and degenerative findings on MRI (in young adults), it does not necessarily imply causation.

Iatrogenic Effects[edit | edit source]

Unnecessary imaging of the lumbar spine can do more harm than good, especially when incidental findings are misinterpreted or poorly conveyed to patients.[1]

- Studies have found that early MRI scans in patients with acute work-related, non-specific low back pain may lead to worse outcomes and a higher risk of surgery (even after controlling for severity).[8]

- Early MRIs may lead to a negative sequelae of unnecessary, ineffective interventions with subsequent poor outcomes.[8]

- See the page on the Nocebo Effect

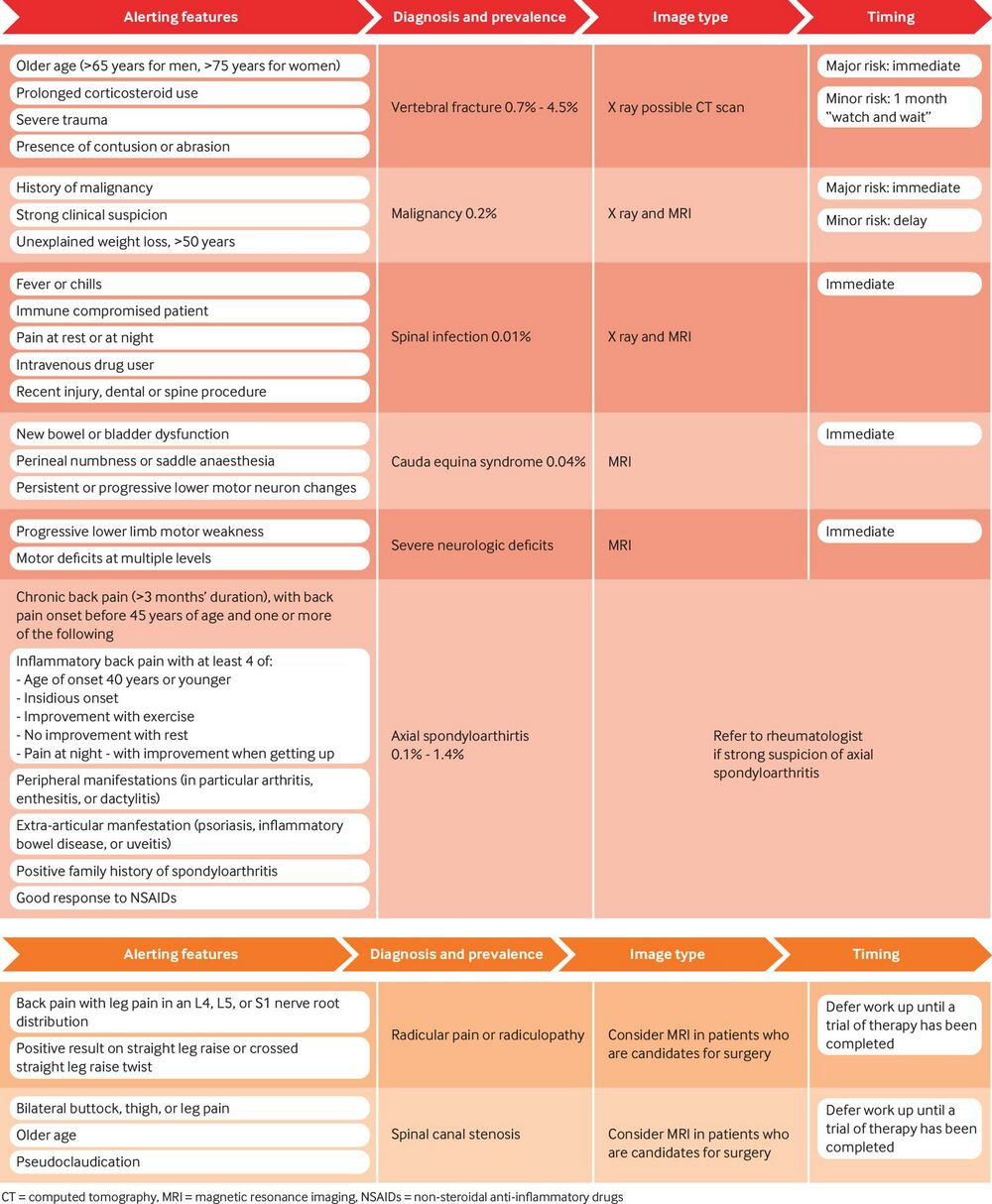

Indications for Imaging[edit | edit source]

Routine imaging or early advanced imaging does not necessarily improve treatment decision-making or patient outcomes and needs to be carefully considered. The following evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for acute low back pain are recommended[1][8]:

- MRI may be indicated when red flags are present or suspected (see image below for further guidelines)

- Infection

- Inflammatory disease

- Cancer

- Fractures

- Severe neurological deficits

- MRI is not indicated for non-specific low back pain. In 90-95% of patients presenting with low back pain, imaging will not inform management and can result in worse outcomes.[1]

- Imaging should be delayed in cases of suspected herniated discs or spinal stenosis to allow for a period of natural recovery (which occurs in up to 50% of cases).

Role of the Physiotherapist[edit | edit source]

In some countries physiotherapists are able to refer for diagnostic imaging, where in other countries referral to a doctor/specialist is needed first. Regardless of country-specific referral protocols, physiotherapists:

- Should be aware of the latest best practice guidelines regarding imaging for low back pain to avoid unnecessary imaging

- Can play an important role in managing patient expectations and beliefs through good communication. This includes reassuring patients that imaging is often not useful, as well as accurately explaining incidental findings[1]

- Should refer for imaging if red flags are present or serious pathology is suspected

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic imaging can be very valuable in patients presenting with lower back pain, especially in the presence of red flags and symptoms that persist. It is however not routinely indicated and can in fact contribute to poor clinical outcomes. Clinicians should be aware of normal feature of ageing, as well as the latest clinical practice guidelines regarding appropriate referral. Imaging should only be considered if it is likely to change/inform patient management. Good communication skills are needed when communicating imaging results to patients.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Patient Education tool on low back pain and imaging

- BMJ article with useful information to include in patient education regarding imaging

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Hall AM, Aubrey-Bassler K, Thorne B, Maher CG. Do not routinely offer imaging for uncomplicated low back pain. bmj. 2021 Feb 12;372.

- ↑ Jenkins HJ, Downie AS, Maher CG, Moloney NA, Magnussen JS, Hancock MJ. Imaging for low back pain: is clinical use consistent with guidelines? A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Spine Journal. 2018 Dec 1;18(12):2266-77.

- ↑ Gross DP, Emery DJ, Long A, Reese H, Whittaker JL. A descriptive study of physiotherapist use of publicly funded diagnostic imaging modalities in Alberta, Canada. European Journal of Physiotherapy. 2018 Oct 10:1-6.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Tang C, Aggarwal R. Imaging for musculoskeletal problems. InnovAiT. 2013 Nov;6(11):735-8.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 McKinnis LN. Fundamentals of musculoskeletal imaging. FA Davis; 2013 Dec 26.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Brinjikji W, Luetmer PH, Comstock B, Bresnahan BW, Chen LE, Deyo RA, Halabi S, Turner JA, Avins AL, James K, Wald JT. Systematic literature review of imaging features of spinal degeneration in asymptomatic populations. American journal of neuroradiology. 2015 Apr 1;36(4):811-6.

- ↑ Brinjikji, W., Diehn, F.E., Jarvik, J.G., Carr, C.M., Kallmes, D.F., Murad, M.H. and Luetmer, P.H., 2015. MRI findings of disc degeneration are more prevalent in adults with low back pain than in asymptomatic controls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 36(12), pp.2394-2399.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Webster BS, Bauer AZ, Choi Y, Cifuentes M, Pransky GS. Iatrogenic consequences of early magnetic resonance imaging in acute, work-related, disabling low back pain. Spine. 2013 Oct 15;38(22):1939-46.