Thoracic Disc Syndrome

This article is currently under review and may not be up to date. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (2/05/2020)

Original Editor - Sarah Harnie

Top Contributors - Sarah Harnie, Maarten Wuijts, Arno Vrambout, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Marleen Moll, Rachael Lowe, Bouzarpour Faryân, Claire Knott, 127.0.0.1, WikiSysop, Abbey Wright, Admin and Evan Thomas

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

'Thoracic syndrome’ is an umbrella term for all pathological clinical manifestations due to functional (physiopathological) disturbances and degenerative changes of the thoracic motion segments. Essentially, we distinguish three kinds of degenerative diseases of the thoracic spine:

- Benign spondylosis and osteochondrosis in the ventral portion of the thoracic motion segments

- disc prolapse into the epidural space with and without clinical signs of spinal cord compression

- Structural and functional disturbances of the intervertebral and costovertebral joints.

Disc disease in the thoracic spine is far less common than in lumbar and cervical regions, it only accounts for 2% of all cases of disc disease and tends to be less serious than disc disease elsewhere in the spine.

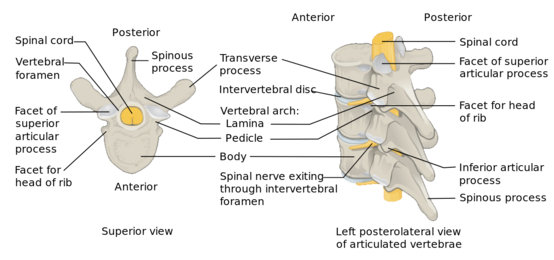

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Key Points

- 12 thoracic discs

- Become broader and higher caudally.

- More flat than the cervical and lumbar discs.

- The thoracic spinal canal is quite narrow (most so from T4-T9), thin epidural space between the spinal cord and surrounding bone or disc.

- Thoracic spine contains the costotransverse joints which indent the lower portion of the intervertebral foramina.

- Thoracic foramina are much wider, bony narrowing such as is seen in the cervical spine, is hardly ever seen here.[1]

- The thoracic spine - relatively rigid part of the spine (compared to the cervical and lumbar spine).

- Stability - direct result of the attachment to the rib cage.

- Facets of the T1-T10 vertebral bodies are oriented vertically (with slight medial angulation in the coronal plane) there is significant stability during flexion and extension, while allowing greater movement in lateral bending and rotation[2].

The active movements (average) in the thoracic spine:

• Forward flexion (20° to 45°)

• Extension (25° to 45°)

• Side flexion, left and right (20° to 40°)

• Rotation, left and right (35° to 50°).[1]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Intervertebral disc degeneration primarily causes thoracic discogenic pain syndrome.

Thoracic disc lesions are primarily degenerative of nature and affect mostly the lower part of the thoracic spine.[2] Three quarters of incidence occurs below T8, with T11-T12 being most common.[3][4] The exact cause of disc degeneration is believed to be multifactorial, factors that can attribute include:

- Trauma

- Metabolic abnormalities

- Genetic predisposition

- Vascular problems

- Infections

The effects of trauma as previously mentioned is less devasting on the thoracic spine as compared to the cervical and lumbar spine because the thoracic spine participates in less weight-bearing activities and the rib cage and coronal orientation of the facet joints make it more stable, hence less prone to degenerative disc disease. With trauma, chronic overload from the lifting of heavy objects or chronic multi-trauma from individuals participating in sports leads to the repeated rotation of the axial spine, causing vertebral instability with alteration of the of the spinal alignment that accelerates the risk of developing disc degeneration.[5]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Why clinically significant thoracic disc disease is less common, has essentially two causes:

- As opposed to the cervical or lumbar spine, the intervertebral foramina of the thoracic spine are located at the level of the body, as opposed to directly behind the discs.

- There is relatively little movement in the thoracic motion segments, so the anatomical relationship of neural structures to their surroundings remains constant.[1]

Thoracic disc herniation is rare and usually asymptomatic.

Often found incidentally with MRI.

Herniation of the intervertebral disc in the thoracic region makes up:

- 0.5% to 4.5% of all disc ruptures

- 0.25-0.75 of all symptomatic disc herniation

- 0.15% and 1.8% of all surgically-treated herniations.[5]

About 80% of patients usually present with problems in the third or fourth decades of life.

About 75% incidence occurs below the T8 with a peak around the T11 to T12 and about 63% are symptomatic and have an incidence of one in one million.

- Note - in acquired deformities of the spine eg scoliosis, Scheuermann disease (which develop gradually) the nerve roots to adapt to the situation not necessarily causing thoracic syndrome.[1]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

- The majority of the thoracic disc herniation are asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally with an MRI.

- Unlike the lumbar and cervical disc herniations, thoracic disc herniations have atypical symptoms and often a diagnosis of exclusion.

- To accurately diagnose thoracic discogenic pain syndrome, a thorough history and physical examination should be done. As part of the patient's pain evaluation, assessment of the quality, intensity, distribution, alleviating, and aggravating factors is essential.

- Degenerative thoracic syndromes can be classified as local, radicular (intercostal neuralgia) or pseudoradicular.

Patients with thoracic disc herniations may either present with a radicular and/or myelopathic pain depending on if the herniated disc compresses the nerve roots or the spinal cord itself, respectively.

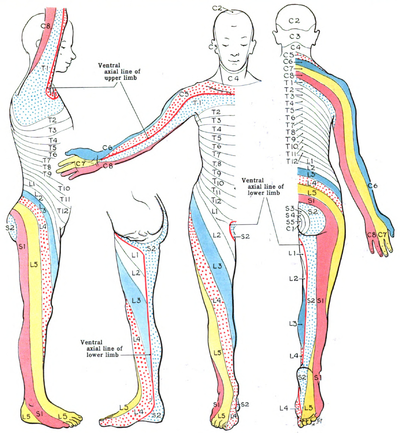

With radicular pain, the patients will have pain that follows the dermatomal distribution.

Essential landmarks for thoracic disc herniations to help with assessment include

- T-1 pain that radiates to the medial forearm,

- T-2 pain that radiates to the axilla,

- T-4 pain that radiates to the nipple area,

- T-10 pain that radiates to the umbilicus

- T-12 pain that is just above the inguinal ligaments.

The most common initial pain is usually thoracic pain occurring in the midline area.

The pain may be:

- unilateral or bilateral depending on the location and how significant the herniation is.

- intermittent and aggravated by coughing and straining.

- In rare cases, radiation to the groin, flank, and even the lower extremities[5].

In upper thoracic and lateral disc herniations

- Radicular pain is more common and often reported in combination with some amount of axial pain.

- Sensory changes (e.g. parenthesias, dysesthesia) below the level of the lesion.

- Other symptoms include bladder and bowel dysfunction (15-20% of patients), hyperreflexia and gait impairment.[1][2]

Red flags one should be aware of are:

- Myelopathy (injury to the spinal cord due to severe compression)

- Gait disturbance

- Paralysis

- Cardiovascular disturbances

- History of:Cancer; Trauma; Tumor; Infection; Constitutional symptoms (feeling ill); Weight loss; Laboratory abnormalities

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Thoracic disc syndrome are relatively rare

- Symptoms in this area will more likely arouse suspicion of disease of the internal organs/ primary disorder of the nervous system.

- Important that the patient is examined thoroughly to rule out all other causes for symptoms.[1][2][6]

Rule out conditions such as

- Diabetes and shingles

- Other mechanical issues such as oblique muscle pain, rib fracture, fracture of the facet joints and clavicle

- Malignancies, like neurofibroma

- Herpes zoster (can cause segmentally radiating pain with postherpetic neuralgia)

- Costotransverse joint syndrome due to inflammatory changes or arthrosis

- Infections, tumors and dilated arteries of the chest wall

- Referred pain from the organs (zones of Head)

- Tietze syndrome

- Scheuermann kyphosis

Pain referred around the chest wall tends to be costovertebral in origin.[7]

Physical examination[edit | edit source]

Start your examination with:

- History eg Chronic or acute, Specific inciting incident, Location of the pain and its radiation, The character of the pain and aggravating activities including static and dynamic load.

- Observation (standing) Examination

- Assessment of sensation with pinprick and touch in the upper extremity, thorax, and abdomen in the dermatomal regions mentioned above to check for radiculopathy and also in the lower extremity to check for myelopathy.

- Active movements (standing or sitting) - Forward flexion - Extension - Side flexion (left and right) - Rotation (left and right) - Combined movements (if necessary) - Repetitive movements (if necessary) - Sustained postures (if necessary)

- Passive movements (sitting) - Forward flexion - Extension - Side flexion (left and right) - Rotation (left and right) - Resisted isometric movements (sitting) - Forward flexion - Extension - Side flexion (left and right) - Rotation (left and right)

- Functional assessment

- Special tests (sitting) - Adson’s test - Costoclavicular maneuver - Hyperabduction (EAST) test - Roos test - Slump test

- Reflexes and cutaneous distribution (sitting) - Reflex testing - Sensation scan

- Special tests (prone lying) - Joint play movements (prone lying) - Posteroanterior central vertebral pressure (PACVP) - Posteroanterior unilateral vertebral pressure (PAUVP) - Transverse vertebral pressure (TVP) - Rib springing - Palpation (prone lying)

- Special tests (supine lying) - First rib mobility - Rib springing - Upper limb neurodynamic (tension) test 4 (ULNT4) - Palpation (supine lying) - Federung test (segmental translation of the thoracic vertebrea)

- Sensitivity of the thorax and stomach

After any assessment, the patient should be warned of the possibility of exacerbation of symptoms as a result of assessment.[7]

Elaboration on some testing

Assess passive movements of the thoracic spine and the end feel:[7]

• Forward flexion (tissue stretch)

• Extension (tissue stretch)

• Side flexion, left and right (tissue stretch)

• Rotation, left and right (tissue stretch)

Pain provocation by performing passive movements, in particular rotation, forward flexion, backward flexion and lateral flexion can indicate a spinal aetiology.

Sensory symptoms can be present if the patient has a thoracic disc herniation. It can cause altered sensation to light touch or pinprick along a dermatomal pattern. Cord compression and myelopathy should be strongly considered if a sensory level is established such that sensation is consistently altered below a specific dermatome.

Provocative manoeuvres such as the Spurling manoeuvre (cervical radiculopathy) and the Straight-Leg Raise test or the Slump Test (lumbosacral radiculopathy) may exclude a thoracic disc syndrome.[1][8][9]

You can also take a look at Thoracic Examination on Physiopedia.

Evaluation[edit | edit source]

In addition to a detailed neurological examination, an MRI of the thoracic spine is very sensitive and specific for diagnosing thoracic disc herniation[10]. In some situations, thoracic discography can be performed to confirm the pain being of discogenic origin being that most thoracic discogenic syndrome can be asymptomatic[5]

Outcome measures[edit | edit source]

- Occiput to Wall Distance

- VAS-pain scale

- Pain Catastrophizing Scale

- Fear-avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire

- Patient Specific Functional Scale

- Fingertips to Floor

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

The initial treatment of thoracic discogenic syndrome is usually conservative (nonoperational) since some disc herniations have been reported to stabilize/regress with time, especially in younger patients.

- Conservative management includes rest, anti-inflammatory drugs, and physical therapy.

- Drugs like Pregabalin have been reported to be useful for the numbness and radicular pain.

- Selective spinal root or intercostal nerve blockade and epidural steroids injections can also be used to treat radicular pain.

- Surgical intervention is considered as a last resort for the treatment of symptomatic thoracic disc herniations with patients unresponsive to conservative treatment.

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Several guidelines recommend physical exercise to alleviate pain. The goal of physiotherapy should be to increase the range of motion and pain relief, using a multiple-exercise based approach to strengthen supporting muscles and postural support.[10][11] Animal model studies show that physical exercise helps in intravertebral disk proliferation, particularly in moderate to high volume low repetition and frequency exercises.[12][13] Most patients (80%) with a prolapsed intervertebral disc respond in 4-6 weeks to conservative therapy.[14][15]

Mechanical strain on the disc can be reduced by horizontal positioning, although bedrest is usually not indicated. The application of heat can bring relief by relaxing the reflexive tension of the thoracic musculature, particularly the paravertebral extensors of the trunk and by promoting circulation.[1]

Some ideas from Physiopedia for physical therapy treatment:

- Exercise in pain management

- Top 3 thoracic spine mobility exercises (Physiospot)

- Thoracic Manual Techniques and Exercises

Case Studies[edit | edit source]

- Unusual chest wall pain caused by thoracic disc herniation in a professional baseball pitcher

- Histologically proven acute paediatric thoracic disc herniation causing paraparesis

- Acute chest pain in a top soccer player due to thoracic disc herniation

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

The term ‘thoracic syndrome’ refers to all pathological clinical manifestations due to functional (physiopathological) disturbances and degenerative changes of the thoracic motion segments.[1] Due to the rarity of this subject, little importance is attached to it in the literature.[16] Articles suggest an incidence between 0.2% and 5.0% of all intervertebral disc herniations with more presentations in males. [17]

Most of the disc disorders are asymptomatic If, nevertheless, symptoms are extant, pain is the most common. Other symptoms may include sensory disturbances, referred pain, weakness in the abdominal and intercostal muscles, paresthesias, weakness of the lower extremities and bladder symptoms.[1][16][8][9][17]

One of the main problems in the treatment of thoracic disc herniation has been the lack of accuracy of diagnostic tests, leaving it to be a diagnosis when other things have been ruled out. Thoracic disc herniation can be revealed by MRI but the relation between symptoms and imaging is low. Musculoskeletal, reflexes, sensory aspects, strength and provocative manoeuvres should be tested.[8][9][1]

Physical therapy should be focussed on increasing the range of motion and pain relief, using a multiple-exercise based approach to strengthen muscles and postural support.[10][11]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedp1 - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:0 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:1 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:2 - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Fogwe DT, Zulfiqar H, Mesfin FB. Thoracic Discogenic Syndrome. InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 Jun 25. StatPearls Publishing. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470388/ (last accessed 2.5.2020)

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:5 - ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:4 - ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedp9 - ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedp0 - ↑ 10.0 10.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:6 - ↑ 11.0 11.1 Manchikanti, Laxmaiah, and Joshua A. Hirsch. "Clinical management of radicular pain." Expert review of neurotherapeutics 15.6 (2015): 681-693.

- ↑ Luan S., Wan Q., Luo H., Li X., Ke S., Lin C., Wu Y., Wu S., Ma C. Running exercise alleviates pain and promotes cell proliferation in a rat model of intervertebral disc degeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:2130–2144

- ↑ Steele J., Bruce-Low S., Smith D., Osborne N., Thorkeldsen A. Can specific loading through exercise impart healing or regeneration of the intervertebral disc? Spine J. Off. J. N. Am. Spine Soc. 2015;15:2117–2121

- ↑ Hofstee, Derk J., et al. "Westeinde sciatica trial: randomized controlled study of bed rest and physiotherapy for acute sciatica." Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine 96.1 (2002): 45-49.

- ↑ Weber, Henrik, Ingar Holme, and Even Amlie. "The natural course of acute sciatica with nerve root symptoms in a double-blind placebo-controlled trial evaluating the effect of piroxicam." Spine 18.11 (1993): 1433-1438.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedp5 - ↑ 17.0 17.1 Jed S. Vanichkachorn, MD and Alexander R. Vaccaro, MD. Thoracic Disk Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2000. 8:159-169.