The Upper Cervical Spine and Cervicogenic Headaches: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

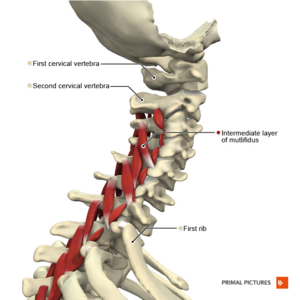

[[File:Muscles of the cervical region multifidus intermediate layer Primal.png| | [[File:Muscles of the cervical region multifidus intermediate layer Primal.png|thumb|Figure 1. Muscles of the cervical region.]] | ||

[[Introduction to Cervicogenic Headaches|Cervicogenic headache]] (CGH) is a chronic secondary headache that originates in the cervical spine.<ref>Fernandez M, Moore C, Tan J, Lian D, Nguyen J, Bacon A et al. Spinal manipulation for the management of cervicogenic headache: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Eur J Pain. 2020; 24(9): 1687-702.</ref> The headache begins in the neck or occipital region and can refer to the face and head. The specific sources of CGH are any structures innervated by the C1 to C3 nerve roots.<ref>Biondi DM. Cervicogenic headache: mechanisms, evaluation, and treatment strategies. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2000;100(9 Suppl): S7-14.</ref> | [[Introduction to Cervicogenic Headaches|Cervicogenic headache]] (CGH) is a chronic secondary headache that originates in the cervical spine.<ref>Fernandez M, Moore C, Tan J, Lian D, Nguyen J, Bacon A et al. Spinal manipulation for the management of cervicogenic headache: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Eur J Pain. 2020; 24(9): 1687-702.</ref> The headache begins in the neck or occipital region and can refer to the face and head. The specific sources of CGH are any structures innervated by the C1 to C3 nerve roots.<ref>Biondi DM. Cervicogenic headache: mechanisms, evaluation, and treatment strategies. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2000;100(9 Suppl): S7-14.</ref> | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

=== Subjective Assessment === | === Subjective Assessment === | ||

The subjective assessment of the cervical spine is discussed [[Cervical Examination|here]], but when a patient reports headaches, it is important to ask specifically about the:<ref name=":0" /> | The subjective assessment of the cervical spine is discussed [[Cervical Examination|here]], but when a patient reports headaches, it is important to ask specifically about the:<ref name=":0" /> | ||

* | * intensity of headaches | ||

* | * frequency of headaches | ||

* | * duration of headaches | ||

=== Objective Assessment === | === Objective Assessment === | ||

A full description of a cervical assessment can be found [[Cervical Examination|here]]. But when assessing for CGH, the following measures should be included:<ref name=":0" /> | A full description of a cervical assessment can be found [[Cervical Examination|here]]. But when assessing for CGH, the following measures should be included:<ref name=":0" /> | ||

* | * range of motion testing | ||

* | * deep neck flexo<nowiki/>r endurance testing | ||

* | * palpation and joint mobility testing | ||

Common clinical methods for assessing cervical spine mobility include:<ref name=":7">Mohamed AA, Shendy WS, Semary M, Mourad HS, Battecha KH, Soliman ES et al. Combined use of cervical headache snag and cervical snag half rotation techniques in the treatment of cervicogenic headache. J Phys Ther Sci. 2019; 31(4): 376-381. </ref> | Common clinical methods for assessing cervical spine mobility include:<ref name=":7">Mohamed AA, Shendy WS, Semary M, Mourad HS, Battecha KH, Soliman ES et al. [https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jpts/31/4/31_jpts-2018-358/_pdf Combined use of cervical headache snag and cervical snag half rotation techniques in the treatment of cervicogenic headache]. J Phys Ther Sci. 2019; 31(4): 376-381. </ref> | ||

* [[Cervical Flexion-Rotation Test| | * [[Cervical Flexion-Rotation Test|flexion rotation test]] | ||

* | * active cervical range of motion | ||

* [[Cervical Examination| | * [[Cervical Examination|passive accessory inter-vertebral movement and physiological inter-vertebral movement]] | ||

* | * active cervical flexion test | ||

* | * myofascial trigger points assessment | ||

* | * cervical [[Sensorimotor Impairment in Neck Pain|proprioception assessment]] | ||

=== Red Flags === | === Red Flags === | ||

It is essential to screen for [[The Flag System|red flags]] and serious conditions in any assessment of the cervical spine. For more information on red flags in spinal conditions, please see this page: [[An Introduction to Red Flags in Serious Pathology]]. | It is essential to screen for [[The Flag System|red flags]] and serious conditions in any assessment of the cervical spine. For more information on red flags in spinal conditions, please see this page: [[An Introduction to Red Flags in Serious Pathology]] and [[Spinal Malignancy]]. | ||

Specific red flags in relation to headache are:<ref>Hall T, Briffa K, Hopper D. Clinical evaluation of cervicogenic headache: a clinical perspective. J Man Manip Ther. 2008; 16(2): 73-80.</ref> | Specific red flags in relation to headache are:<ref>Hall T, Briffa K, Hopper D. Clinical evaluation of cervicogenic headache: a clinical perspective. J Man Manip Ther. 2008; 16(2): 73-80.</ref> | ||

* | * sudden onset of a new, severe headache | ||

* | * a worsening pattern of a pre-existing headache in the absence of any clear predisposing factors | ||

* | * headache that is associated with fever, neck stiffness, skin rash, and with a history of cancer, HIV, or other systemic illness | ||

* | * headache that is associated with focal neurologic signs other than a typical [[Headaches and Dizziness|aura]] | ||

* | * moderate or severe headache triggered by cough, exertion, or bearing down | ||

* | * new onset of a headache during or following pregnancy | ||

Serious conditions include: | Serious conditions include: | ||

* [[Vascular Pathologies of the Neck| | * [[Vascular Pathologies of the Neck|cranial artery dysfunction]] | ||

** | ** cervical artery | ||

** | ** carotid artery | ||

* | ** please see [[International Framework for Examination of the Cervical Region]] for more information on the cervical risk assessment | ||

* [[Cervical Instability| | * intracranial issues | ||

** [[Transverse Ligament of the Atlas| | * [[Cervical Instability|upper cervical ligament instability]] (see below): | ||

** [[Alar ligaments| | ** [[Transverse Ligament of the Atlas|transverse ligament]] | ||

** [[Alar ligaments|alar ligament]] | |||

==== Upper Cervical Ligament Instability ==== | ==== Upper Cervical Ligament Instability ==== | ||

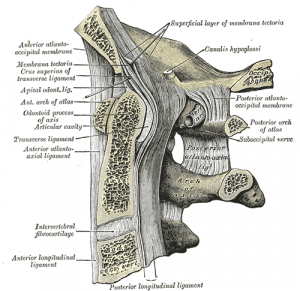

[[File:Upper cervical ligaments.png| | [[File:Upper cervical ligaments.png|thumb|Figure 2. Ligaments of the cervical spine.]] | ||

Upper cervical ligament instability has a prevalence rate of 0.6 percent,<ref name=":1">Hutting N, Scholten-Peeters GG, Vijverman V, Keesenberg MD, Verhagen AP. Diagnostic accuracy of upper cervical spine instability tests: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2013; 93(12): 1686-95. </ref> but it is more common in patients with inflammatory arthritis (e.g. [[Rheumatoid Arthritis|rheumatoid arthritis]]).<ref>Takahashi S, Suzuki A, Koike T, Yamada K, Yasuda H, Tada M, Sugioka Y et al. Current prevalence and characteristics of cervical spine instability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the era of biologics. Mod Rheumatol. 2014; 24(6): 904-9. </ref><ref>Al-Daoseri HA, Mohammed Saeed MA, Ahmed RA. Prevalence of cervical spine instability among Rheumatoid Arthritis patients in South Iraq. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma. 2020; 11(5): 876-82. </ref> Despite low prevalence rates in the general population, it is important to screen for these conditions. | Upper cervical ligament instability has a prevalence rate of 0.6 percent,<ref name=":1">Hutting N, Scholten-Peeters GG, Vijverman V, Keesenberg MD, Verhagen AP. Diagnostic accuracy of upper cervical spine instability tests: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2013; 93(12): 1686-95. </ref> but it is more common in patients with inflammatory arthritis (e.g. [[Rheumatoid Arthritis|rheumatoid arthritis]]).<ref>Takahashi S, Suzuki A, Koike T, Yamada K, Yasuda H, Tada M, Sugioka Y et al. Current prevalence and characteristics of cervical spine instability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the era of biologics. Mod Rheumatol. 2014; 24(6): 904-9. </ref><ref>Al-Daoseri HA, Mohammed Saeed MA, Ahmed RA. Prevalence of cervical spine instability among Rheumatoid Arthritis patients in South Iraq. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma. 2020; 11(5): 876-82. </ref> Despite low prevalence rates in the general population, it is important to screen for these conditions. | ||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

The Sharp Purser test is commonly used in clinical practice to assess for atlantoaxial instability, particularly in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.<ref name=":2">Mansfield CJ, Domnisch C, Iglar L, Boucher L, Onate J, Briggs M. Systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy, reliability, and safety of the sharp-purser test. J Man Manip Ther. 2020; 28(2): 72-81.</ref> This test is discussed in more detail [[Sharp Purser Test|here]]. | The Sharp Purser test is commonly used in clinical practice to assess for atlantoaxial instability, particularly in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.<ref name=":2">Mansfield CJ, Domnisch C, Iglar L, Boucher L, Onate J, Briggs M. Systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy, reliability, and safety of the sharp-purser test. J Man Manip Ther. 2020; 28(2): 72-81.</ref> This test is discussed in more detail [[Sharp Purser Test|here]]. | ||

Please watch this video for a demonstration of the Sharp Purser test. | |||

{{#ev:youtube|eqS2tIGauXU}}<ref>The Physio Channel. How to perform the Sharp-Purser Atlanto Axial Joint Test for instability. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eqS2tIGauXU [last accessed 6/12/2020]</ref> | {{#ev:youtube|eqS2tIGauXU}}<ref>The Physio Channel. How to perform the Sharp-Purser Atlanto Axial Joint Test for instability. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eqS2tIGauXU [last accessed 6/12/2020]</ref> | ||

| Line 68: | Line 70: | ||

===== Alar Ligament ===== | ===== Alar Ligament ===== | ||

The alar ligaments act to stabilise the cervical spine but can be damaged following trauma. It is important that they are assessed, particularly in patients who have neck dysfunction following injury.<ref name=":3">Harry Von P, Maloul R, Hoffmann M, Hall T, Ruch MM, Ballenberger N. Diagnostic accuracy and validity of three manual examination tests to identify alar ligament lesions: results of a blinded case-control study. J Man Manip Ther. 2019; 27(2): 83-91. </ref> The gold standard test is MRI, but when this is not available, there are a number of clinical tests that can be used, including:<ref name=":3" /> | The alar ligaments act to stabilise the cervical spine but can be damaged following trauma. It is important that they are assessed, particularly in patients who have neck dysfunction following injury.<ref name=":3">Harry Von P, Maloul R, Hoffmann M, Hall T, Ruch MM, Ballenberger N. Diagnostic accuracy and validity of three manual examination tests to identify alar ligament lesions: results of a blinded case-control study. J Man Manip Ther. 2019; 27(2): 83-91. </ref> The gold standard test is MRI, but when this is not available, there are a number of clinical tests that can be used, including:<ref name=":3" /> | ||

* [[Alar Ligament Test| | * [[Alar Ligament Test|side-bending stress test]] | ||

* | * rotation stress test | ||

* | * lateral shear test | ||

In a recent study, the sensitivity and specificity of these tests were found to range from 80. to 85.7 percent and 69.2 to 90.9 percent, respectively. Positive and negative likelihood ratios ranged from 2.6 to 9.41 and 0.15 to 0.26, respectively. These figures indicate that these tests are only of small-to-moderate clinical diagnostic value. However, when used as a cluster of tests, the sensitivity and specificity were to 85.7 percent and 100 percent, respectively if more than two tests were positive. Likelihood ratios improved to infinity (positive likelihood ratio) and 0.15 (negative likelihood ratio). These ratios indicate that this cluster of tests has moderate-to-excellent clinical diagnostic value.<ref name=":3" /> | In a recent study, the sensitivity and specificity of these tests were found to range from 80. to 85.7 percent and 69.2 to 90.9 percent, respectively. Positive and negative likelihood ratios ranged from 2.6 to 9.41 and 0.15 to 0.26, respectively. These figures indicate that these tests are only of small-to-moderate clinical diagnostic value. However, when used as a cluster of tests, the sensitivity and specificity were to 85.7 percent and 100 percent, respectively if more than two tests were positive. Likelihood ratios improved to infinity (positive likelihood ratio) and 0.15 (negative likelihood ratio). These ratios indicate that this cluster of tests has moderate-to-excellent clinical diagnostic value.<ref name=":3" /> | ||

| Line 88: | Line 90: | ||

NB: this test is affected by the degree of flexion the clinician places the patient’s head in. If the head is not fully flexed, the AA joint will not be isolated. This can result in false-negative results. Thus, this test can be affected by a patient’s pain levels and ability to tolerate full cervical flexion.<ref name=":0" /> | NB: this test is affected by the degree of flexion the clinician places the patient’s head in. If the head is not fully flexed, the AA joint will not be isolated. This can result in false-negative results. Thus, this test can be affected by a patient’s pain levels and ability to tolerate full cervical flexion.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

Please watch the following video for a summary and demonstration of the cervical flexion rotation test. | |||

{{#ev:youtube|4NIshu8tGA4}}<ref>Physical Therapy Nation. Flexion Rotation Test. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4NIshu8tGA4 [last accessed 7/12/2020]</ref> | {{#ev:youtube|4NIshu8tGA4}}<ref>Physical Therapy Nation. Flexion Rotation Test. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4NIshu8tGA4 [last accessed 7/12/2020]</ref> | ||

| Line 98: | Line 102: | ||

Treatments for the upper cervical segments include: | Treatments for the upper cervical segments include: | ||

* | * cervical spine mobilisations or manipulations<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":5">Hall T, Chan HT, Christensen L, Odenthal B, Wells C, Robinson K. Efficacy of a C1-C2 self-sustained natural apophyseal glide (SNAG) in the management of cervicogenic headache. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007; 37(3): 100-107.</ref> | ||

* | * strengthening exercises<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":8">Jull GA, Falla D, Vicenzino B, Hodges PW. The effect of therapeutic exercise on activation of the deep cervical flexor muscles in people with chronic neck pain. Man Ther. 2009; 14(6): 696-701. </ref> | ||

* | * soft tissue techniques<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":6" /><ref name=":9" /> | ||

=== Specific Mobilisation Techniques === | === Specific Mobilisation Techniques === | ||

* Posterior to anterior mobilisation for the AA joint and C2-3<ref name=":0" /> | * Posterior to anterior mobilisation for the AA joint and C2-3<ref name=":0" /> | ||

** | ** palpate C2 spinous process (i.e. the first spinous process that can be felt when coming off the occiput) | ||

** | ** move slightly laterally | ||

** | ** provide a small oscillatory force on the articular pillar | ||

In order to preferentially mobilise the AA joint over C2-3, rotate the patient’s head slightly (around 20 to 30 degrees). This will take up the slack in the AA joint.<ref name=":0" /> | In order to preferentially mobilise the AA joint over C2-3, rotate the patient’s head slightly (around 20 to 30 degrees). This will take up the slack in the AA joint.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| Line 112: | Line 116: | ||

To target the OA joint:<ref name=":0" /> | To target the OA joint:<ref name=":0" /> | ||

* | * find the C2 spinous process and move superiorly. This is where C1 (i.e. the atlas is located) | ||

* | * a posterior-anterior mobilisation on C1 can be performed to recreate and treat headache | ||

=== Exercise Therapy === | === Exercise Therapy === | ||

| Line 122: | Line 126: | ||

NB the pressure from the towel should not be too firm. Rather it should simply assist movement. It is important to practise the techniques in the clinic first to ensure that the patient understands how to do this stretch properly.<ref name=":0" /> | NB the pressure from the towel should not be too firm. Rather it should simply assist movement. It is important to practise the techniques in the clinic first to ensure that the patient understands how to do this stretch properly.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

The following videos demonstrates how the AA Self-SNAG technique is performed. | |||

{{#ev:youtube|NPl3u2-dixE}}<ref>[P]Rehab. SNAGs for Cervicogenic Headaches. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NPl3u2-dixE [last accessed 7/12/2020]</ref> | {{#ev:youtube|NPl3u2-dixE}}<ref>[P]Rehab. SNAGs for Cervicogenic Headaches. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NPl3u2-dixE [last accessed 7/12/2020]</ref> | ||

| Line 132: | Line 138: | ||

==== Deep Neck Flexor Training ==== | ==== Deep Neck Flexor Training ==== | ||

Deep neck flexor training can also help to reinforce improvements, particularly at the OA joint. Jull and colleagues found that six weeks of performing craniocervical flexion exercises were as effective as spinal manipulation at reducing cervical pain, and headache frequency and intensity for up to one year.<ref name=":8" /> This exercise programme is discussed in more detail [[Cervicogenic Headache|here]]. | Deep neck flexor training can also help to reinforce improvements, particularly at the OA joint. Jull and colleagues found that six weeks of performing craniocervical flexion exercises were as effective as spinal manipulation at reducing cervical pain, and headache frequency and intensity for up to one year.<ref name=":8" /> This exercise programme is discussed in more detail [[Cervicogenic Headache|here]]. | ||

Please watch this video for a demonstration of how to perform these exercises. | |||

{{#ev:youtube|okmuO_6TT0s}}<ref>BSR Physical Therapy. Craniocervical Flexion Exercise. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=okmuO_6TT0s [last accessed 6/12/2020]</ref> | {{#ev:youtube|okmuO_6TT0s}}<ref>BSR Physical Therapy. Craniocervical Flexion Exercise. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=okmuO_6TT0s [last accessed 6/12/2020]</ref> | ||

| Line 137: | Line 145: | ||

=== Soft Tissue Techniques === | === Soft Tissue Techniques === | ||

There are a variety of soft tissue techniques that may be helpful for suboccipital dysfunction, including: | There are a variety of soft tissue techniques that may be helpful for suboccipital dysfunction, including: | ||

* | * muscle energy techniques<ref name=":0" /> | ||

* [[Instrument Assisted Soft Tissue Mobilization| | * [[Instrument Assisted Soft Tissue Mobilization|instrument assisted soft tissue mobilisation]]<ref name=":6" /> | ||

* | * muscle stretching<ref name=":6" /> | ||

* | * trigger point therapy<ref name=":9">Bodes-Pardo G, Pecos-Martín D, Gallego-Izquierdo T, Salom-Moreno J, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Ortega-Santiago R. Manual treatment for cervicogenic headache and active trigger point in the sternocleidomastoid muscle: a pilot randomized clinical trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013; 36(7): 403-11.</ref> | ||

== Summary == | == Summary == | ||

Latest revision as of 17:55, 28 February 2024

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Cervicogenic headache (CGH) is a chronic secondary headache that originates in the cervical spine.[1] The headache begins in the neck or occipital region and can refer to the face and head. The specific sources of CGH are any structures innervated by the C1 to C3 nerve roots.[2]

When assessing and treating patients with CGH, it is important to be able to clearly identify the symptomatic area in the upper cervical spine. Areas to assess are the:[3]

- Atlanto-occipital joint (C0-1)

- Atlanto-axial (AA) joint (C1-2)

- C2-3 joint

- Suboccipital muscles

Headache Assessment[edit | edit source]

Subjective Assessment[edit | edit source]

The subjective assessment of the cervical spine is discussed here, but when a patient reports headaches, it is important to ask specifically about the:[3]

- intensity of headaches

- frequency of headaches

- duration of headaches

Objective Assessment[edit | edit source]

A full description of a cervical assessment can be found here. But when assessing for CGH, the following measures should be included:[3]

- range of motion testing

- deep neck flexor endurance testing

- palpation and joint mobility testing

Common clinical methods for assessing cervical spine mobility include:[4]

- flexion rotation test

- active cervical range of motion

- passive accessory inter-vertebral movement and physiological inter-vertebral movement

- active cervical flexion test

- myofascial trigger points assessment

- cervical proprioception assessment

Red Flags[edit | edit source]

It is essential to screen for red flags and serious conditions in any assessment of the cervical spine. For more information on red flags in spinal conditions, please see this page: An Introduction to Red Flags in Serious Pathology and Spinal Malignancy.

Specific red flags in relation to headache are:[5]

- sudden onset of a new, severe headache

- a worsening pattern of a pre-existing headache in the absence of any clear predisposing factors

- headache that is associated with fever, neck stiffness, skin rash, and with a history of cancer, HIV, or other systemic illness

- headache that is associated with focal neurologic signs other than a typical aura

- moderate or severe headache triggered by cough, exertion, or bearing down

- new onset of a headache during or following pregnancy

Serious conditions include:

- cranial artery dysfunction

- cervical artery

- carotid artery

- please see International Framework for Examination of the Cervical Region for more information on the cervical risk assessment

- intracranial issues

- upper cervical ligament instability (see below):

Upper Cervical Ligament Instability[edit | edit source]

Upper cervical ligament instability has a prevalence rate of 0.6 percent,[6] but it is more common in patients with inflammatory arthritis (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis).[7][8] Despite low prevalence rates in the general population, it is important to screen for these conditions.

Transverse Ligament[edit | edit source]

The transverse ligament enables the atlas to pivot on the axis. It holds the atlas in its correct position in order to prevent spinal cord compression during neck and head flexion.[9]

The Sharp Purser test is commonly used in clinical practice to assess for atlantoaxial instability, particularly in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.[10] This test is discussed in more detail here.

Please watch this video for a demonstration of the Sharp Purser test.

Use of the sharp purser test is, however, considered contentious due to its potential to cause harm (i.e. a positive sharp purser test involves compressing the spinal cord via the dens of C2 and then performing a manoeuvre to decrease pressure on the spinal cord. This could be unsafe in high-risk populations).[10] While there is currently no evidence to suggest that this test is harmful, there is a lack of evidence on its use in high-risk populations. It also demonstrates inconsistent validity and poor inter-rater reliability.[10]

Other tests include the transverse ligament stress test. This test has high enough specificity to rule in patients with upper cervical spine instability. However, when Hutting and colleagues looked at a range of instability tests, they concluded that it is not currently possible to accurately screen for upper cervical instability.[6]

Alar Ligament[edit | edit source]

The alar ligaments act to stabilise the cervical spine but can be damaged following trauma. It is important that they are assessed, particularly in patients who have neck dysfunction following injury.[12] The gold standard test is MRI, but when this is not available, there are a number of clinical tests that can be used, including:[12]

- side-bending stress test

- rotation stress test

- lateral shear test

In a recent study, the sensitivity and specificity of these tests were found to range from 80. to 85.7 percent and 69.2 to 90.9 percent, respectively. Positive and negative likelihood ratios ranged from 2.6 to 9.41 and 0.15 to 0.26, respectively. These figures indicate that these tests are only of small-to-moderate clinical diagnostic value. However, when used as a cluster of tests, the sensitivity and specificity were to 85.7 percent and 100 percent, respectively if more than two tests were positive. Likelihood ratios improved to infinity (positive likelihood ratio) and 0.15 (negative likelihood ratio). These ratios indicate that this cluster of tests has moderate-to-excellent clinical diagnostic value.[12]

Range of Motion[edit | edit source]

Cervical range of motion is typically included as part of a cervical spine assessment. While it has been found that its inclusion is of some value, clinical conclusions should not be made based on range of motion alone.[13]

OA Joint (C0-1)[edit | edit source]

This joint can be assessed with a simple nodding test, which effectively isolates the OA joint.[3]

AA Joint (C1-2)[edit | edit source]

Cervicogenic headache patients are most likely to have dysfunction at the AA joint. This segment has been found to be symptomatic in 63 to 70 percent of patients with this condition.[14] It is, therefore, vital that the clinician is able to identify dysfunction at this joint.[3]

Cervical flexion rotation test[edit | edit source]

The cervical flexion rotation test has been found to have the highest reliability and strongest diagnostic accuracy for cervicogenic headache.[14] Its sensitivity is 91 percent and its specificity 90 percent. Its overall diagnostic accuracy is 91 percent.[15]

A normal result is rotation of 40 degrees or more. An abnormal measurement is below 32 degrees. This result would indicate dysfunction at the AA joint (C1-2).[3]

NB: this test is affected by the degree of flexion the clinician places the patient’s head in. If the head is not fully flexed, the AA joint will not be isolated. This can result in false-negative results. Thus, this test can be affected by a patient’s pain levels and ability to tolerate full cervical flexion.[3]

Please watch the following video for a summary and demonstration of the cervical flexion rotation test.

Suboccipital Muscles[edit | edit source]

Dysfunction in these muscles can be identified by palpation.[3]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Because CGH is associated with musculoskeletal dysfunction and muscle imbalance, a multimodal management approach that focuses on a patient's specific impairments is necessary.[17]

Treatments for the upper cervical segments include:

- cervical spine mobilisations or manipulations[17][18]

- strengthening exercises[17][19]

- soft tissue techniques[3][17][20]

Specific Mobilisation Techniques[edit | edit source]

- Posterior to anterior mobilisation for the AA joint and C2-3[3]

- palpate C2 spinous process (i.e. the first spinous process that can be felt when coming off the occiput)

- move slightly laterally

- provide a small oscillatory force on the articular pillar

In order to preferentially mobilise the AA joint over C2-3, rotate the patient’s head slightly (around 20 to 30 degrees). This will take up the slack in the AA joint.[3]

If the head remains straight, C2-3 joint will be preferentially mobilised.

To target the OA joint:[3]

- find the C2 spinous process and move superiorly. This is where C1 (i.e. the atlas is located)

- a posterior-anterior mobilisation on C1 can be performed to recreate and treat headache

Exercise Therapy[edit | edit source]

It is important to prescribe exercises that will reinforce manual techniques.[3]

AA Self-SNAG[edit | edit source]

Place towel or similar item about the atlas to mobilise the AA joint (or slightly lower for C2-3). Use the towel to guide the neck into rotation.[3]

NB the pressure from the towel should not be too firm. Rather it should simply assist movement. It is important to practise the techniques in the clinic first to ensure that the patient understands how to do this stretch properly.[3]

The following videos demonstrates how the AA Self-SNAG technique is performed.

Evidence[edit | edit source]

AA joint SNAGs have been shown to improve cervical flexion-rotation[4][22] A recent study by Mohamed and colleagues found that when the AA joint SNAG mobilisation was used in conjunction with a headache SNAG, there is an even greater reduction in headache and dizziness symptoms.[4]

- Headache SNAG = ventral gliding on C2 while the patient is positioned sitting on a chair.

Patients who practised the self-SNAG described above two times per day for 12 months had a 54 percent reduction in headache index scores at 12 months, compared to a 13 percent reduction in the control group.[18]

Deep Neck Flexor Training[edit | edit source]

Deep neck flexor training can also help to reinforce improvements, particularly at the OA joint. Jull and colleagues found that six weeks of performing craniocervical flexion exercises were as effective as spinal manipulation at reducing cervical pain, and headache frequency and intensity for up to one year.[19] This exercise programme is discussed in more detail here.

Please watch this video for a demonstration of how to perform these exercises.

Soft Tissue Techniques[edit | edit source]

There are a variety of soft tissue techniques that may be helpful for suboccipital dysfunction, including:

- muscle energy techniques[3]

- instrument assisted soft tissue mobilisation[17]

- muscle stretching[17]

- trigger point therapy[20]

Summary[edit | edit source]

- CGH begins in the neck or occipital region. The specific sources of CGH are any structures innervated by the C1 to C3 nerve roots

- The physiotherapist must carry out a detailed subjective and objective assessment, which includes screening for any red flags

- The objective assessment should highlight which area/s are causing the headache

- Treatment must be targeted towards the individual's specific dysfunction, but a multimodal approach of manual techniques and exercise therapy have been found to be beneficial in treating this headache condition

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Fernandez M, Moore C, Tan J, Lian D, Nguyen J, Bacon A et al. Spinal manipulation for the management of cervicogenic headache: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Eur J Pain. 2020; 24(9): 1687-702.

- ↑ Biondi DM. Cervicogenic headache: mechanisms, evaluation, and treatment strategies. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2000;100(9 Suppl): S7-14.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 Kaplan A. Cervicogenic Headache - Upper Cervical Course. Plus , 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Mohamed AA, Shendy WS, Semary M, Mourad HS, Battecha KH, Soliman ES et al. Combined use of cervical headache snag and cervical snag half rotation techniques in the treatment of cervicogenic headache. J Phys Ther Sci. 2019; 31(4): 376-381.

- ↑ Hall T, Briffa K, Hopper D. Clinical evaluation of cervicogenic headache: a clinical perspective. J Man Manip Ther. 2008; 16(2): 73-80.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hutting N, Scholten-Peeters GG, Vijverman V, Keesenberg MD, Verhagen AP. Diagnostic accuracy of upper cervical spine instability tests: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2013; 93(12): 1686-95.

- ↑ Takahashi S, Suzuki A, Koike T, Yamada K, Yasuda H, Tada M, Sugioka Y et al. Current prevalence and characteristics of cervical spine instability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the era of biologics. Mod Rheumatol. 2014; 24(6): 904-9.

- ↑ Al-Daoseri HA, Mohammed Saeed MA, Ahmed RA. Prevalence of cervical spine instability among Rheumatoid Arthritis patients in South Iraq. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma. 2020; 11(5): 876-82.

- ↑ Cramer GD. The cervical region. In: Cramer GD, Darby SA editors. Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans. Elsevier, 2014. p135-209.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Mansfield CJ, Domnisch C, Iglar L, Boucher L, Onate J, Briggs M. Systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy, reliability, and safety of the sharp-purser test. J Man Manip Ther. 2020; 28(2): 72-81.

- ↑ The Physio Channel. How to perform the Sharp-Purser Atlanto Axial Joint Test for instability. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eqS2tIGauXU [last accessed 6/12/2020]

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Harry Von P, Maloul R, Hoffmann M, Hall T, Ruch MM, Ballenberger N. Diagnostic accuracy and validity of three manual examination tests to identify alar ligament lesions: results of a blinded case-control study. J Man Manip Ther. 2019; 27(2): 83-91.

- ↑ Snodgrass SJ, Cleland JA, Haskins R, Rivett DA. The clinical utility of cervical range of motion in diagnosis, prognosis, and evaluating the effects of manipulation: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2014; 100(4): 290-304.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Rubio-Ochoa J, Benítez-Martínez J, Lluch E, Santacruz-Zaragozá S, Gómez-Contreras P, Cook CE. Physical examination tests for screening and diagnosis of cervicogenic headache: A systematic review. Man Ther. 2016; 21: 35-40.

- ↑ Ogince M, Hall T, Robinson K, Blackmore AM. The diagnostic validity of the cervical flexion-rotation test in C1/2-related cervicogenic headache. Man Ther. 2007; 12(3): 256-62.

- ↑ Physical Therapy Nation. Flexion Rotation Test. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4NIshu8tGA4 [last accessed 7/12/2020]

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 Page P. Cervicogenic headaches: an evidence-led approach to clinical management. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2011; 6(3): 254-266.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Hall T, Chan HT, Christensen L, Odenthal B, Wells C, Robinson K. Efficacy of a C1-C2 self-sustained natural apophyseal glide (SNAG) in the management of cervicogenic headache. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007; 37(3): 100-107.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Jull GA, Falla D, Vicenzino B, Hodges PW. The effect of therapeutic exercise on activation of the deep cervical flexor muscles in people with chronic neck pain. Man Ther. 2009; 14(6): 696-701.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Bodes-Pardo G, Pecos-Martín D, Gallego-Izquierdo T, Salom-Moreno J, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Ortega-Santiago R. Manual treatment for cervicogenic headache and active trigger point in the sternocleidomastoid muscle: a pilot randomized clinical trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013; 36(7): 403-11.

- ↑ [P]Rehab. SNAGs for Cervicogenic Headaches. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NPl3u2-dixE [last accessed 7/12/2020]

- ↑ Kocjan J. Effect of a C1-2 Mulligan sustained natural apophyseal glide (SNAG) in the treatment of cervicogenic headache. J of Education, Health, and Sport. 2015; 5(6): 79-87.

- ↑ BSR Physical Therapy. Craniocervical Flexion Exercise. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=okmuO_6TT0s [last accessed 6/12/2020]