Cervicogenic Headache

Original Editor - Christopher Covert

Top Contributors - Jeremy Brady, Admin, Sofie Van Cutsem, Kim Jackson, Nicolas D'Hondt, Mary Harris, Rick Wetherald, Rani Vetsuypens, Sanne Vanderhoeven, Joshua Samuel, Rachael Lowe, Laura Ritchie, Evan Thomas, Tony Lowe, 127.0.0.1, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Christopher Covert, Bram Sorel, Lucinda hampton, Jess Bell, Chelsea Mclene, Rishika Babburu, Scott Buxton, Mathieu Van Durme1, WikiSysop, Vidya Acharya, Rucha Gadgil and Olajumoke Ogunleye

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

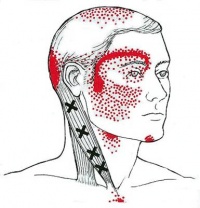

Cervicogenic headache (CGH) is a chronic headache that arises from the atlanto-occipital and upper cervical joints and perceived in one or more regions of the head and/or face.[1]

A cervicogenic headache is a common cause of a chronic headache that is often misdiagnosed. The presenting features can be complex and similar to many primary headache syndromes that are encountered daily. The main symptoms of a cervicogenic headache are a combination of unilateral pain, ipsilateral diffuse shoulder, and arm pain. ROM in the neck is reduced, and pain is relieved with anesthetic blockades.

The International Headache Society (IHS) has validated cervicogenic headache as a secondary headache type that is hypothesized to originate due to nociception in the cervical area. [2] (See more about classification on the headache page).

Clinical Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

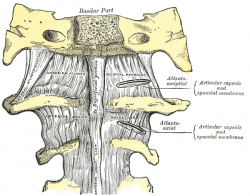

The cervical spine consists of 7 vertebrae, C1 to C7, the cervical nerves from C1 to C8, muscles and ligaments (see cervical Anatomy)

The first two vertebrae have a unique shape and function.[3] They form the upper cervical spine.

- The upper vertebrae supports the skull (atlas/C1), articulates superiorly with the occiput (the atlanto-occipital joint) . This joint is responsible for 33% of flexion and extension.The design of the atlas allows forward and backward movement of the head.

- Below the atlas is the axis (C2) that allows rotation.[3] The atlantoaxial joint is responsible for 60% of all cervical rotation.

- The 5 cervical vertebrae that make up the lower cervical spine, C3-C7, are similar to each other but very different from C1 and C2.

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

- The C1-C3 nerves relay pain signals to the nociceptive nucleus of the head and neck, the trigeminocervical nucleus. This connection is thought to be the cause for referred pain to the occiput and/or eyes. (Wang 2014).

- Aseptic inflammation and neurotransmission within the C-fibers that is caused by cervical disc pathology is thought to produce and worsen the pain in a cervicogenic headache.

- The trigeminocervical nucleus receives afferents from the trigeminal nerve as well as the upper three cervical spinal nerves. Neck trauma, whiplash, strain, or chronic spasm of the scalp, neck, or shoulder muscles can increase the sensitivity of the area which is similar to the allodynia that is seen in late chronic migraines.

- A lower pain threshold makes patients more susceptible to more severe pain. For this reason, early diagnosis and therapeutic intervention is very important[4].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

- A cervicogenic headache is a rare chronic headache in people who are 30 to 44 years old.

- Its prevalence among patients with headaches is 1% to 4%, depending on how many criteria fulfilled and based on many different studies.

- It affects males and females about the same with a ratio of 0.97 (F/M ratio).

- Age at onset is thought to be the early 30s, but the age the patients seek medical attention and diagnosis is 49.4.

- When compared with other headache patients, these patients have a pericranial muscle tenderness on the painful side[4]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

A cervicogenic headache is thought to be referred pain arising from irritation caused by cervical structures innervated by spinal nerves C1, C2, and C3; therefore, any structure innervated by the C1–C3 spinal nerves could be the source for a cervicogenic headache.[4]

This may include the joints, disc, ligaments, and musculature.[5] The lower cervical spine may play an indirect role in pain production if dysfunctional, but there is no evidence of a direct referral pattern.[5] Through controlled nerve blocking of various structures in the cervical spine, it appears that the zygoapophyseal joints, especially those of C2/C3, are the most common sources of CGH pain. This finding is even more common in patients with a history of whiplash. [5]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Challenging to diagnose clinically, but often includes the below:

- Unilateral “ram’s horn” or unilateral dominant headache[6] (Excluding those with bilateral headache or symptoms that typify migraine headaches).

- Exacerbated by neck movement or posture[6]

- Tenderness of the upper 3 cervical spine joints[6]

- Association with neck pain or dysfunction[7]

- Definitive diagnosis made through selective nerve blocking through injection of specific sites[5]

- Compared to migraine headache and control groups, cervicogenic headache group patients tend to have increased tightness and trigger points in upper trapezius, levator scapulae, scalenes[8] and suboccipital extensors[1]

- Weakness in the deep neck flexors[9][10][11]

- Increased activity in the superficial flexors

- Atrophy in the suboccipital extensors and so the deep muscle sleeve which is important for active support of the cervical segments becomes impaired

- Upper trapezius, sternocleidomastoid, scalenes, levator scapulae, pectoralis major and minor, and short sub-occipital extensors have been implicated[9][10][12]

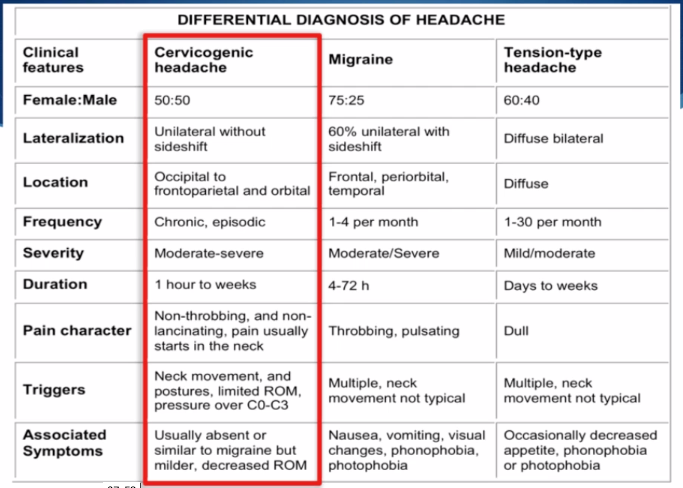

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

It is important to differentiate from serious pathology such as:

- Vascular Pathologies of the Neck

- Intracranial Pathology

- Cervical Instability

- Cervical Myelopathy

- Occipital neuralgia

It is also important to differentiate from other types of headache:

| Type | Location | Intensity | Frequency | Duration | Additional Symptoms |

| Cluster | Unilateral: (orbital, supraorbital, temporal) | Severe | 1x every other day -> 8x day | 15-180 minutes | Associated with ipsilateral: conjunctival injection, lacrimation, nasal congestion, rhinorrhoea, forehead and facial sweating, miosis, ptosis, eyelid edema. Restlessness or agitation. |

| Tension | Bilateral | Mild-Moderate | >15day/mo, >3 mo | Hours-continuous |

Pressing, tightening <1 of photophobia, phonophobia or mild nausea |

| Migraine without aura | Unilateral: Frontotemporal in adults, Occipital in children | Moderate-Severe | >14 days/month |

4-72 hours | Flickering lights/spots in vision, pulsating quality, nausea, photophobia, phonophobia |

| Cluster | Tension | Migrane |

|

|

|

|

For more detailed classification information

Outcomes Measures[edit | edit source]

- Neck Disability Index

- Headache Disability Index

- The Northwick Park Questionnaire

- Neck Pain and Disability Scale

- Numeric Pain Rating Scale

- Pain visual analog scale

Examination[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic Criteria

As described by the IHS[13]:

- Pain localized in the neck and occiput, which can spread to other areas in the head, such as forehead, orbital region, temples, vertex, or ears, usually unilateral.

- Pain is precipitated or aggravated by specific neck movements or sustained postures.

- At least one of the following:

- Resistance to or limitation of passive neck movements

- Changes in neck muscle contour, texture, tone, or response to active and passive stretching and contraction

- Abnormal tenderness of neck musculature

- Radiological examination reveals at least one of the following:

- Movement abnormalities in flexion/extension

- Abnormal posture

- Fractures, congenital abnormalities, bone tumors, rheumatoid arthritis, or other distinct pathology (not spondylosis or osteochondrosis)

Flexion-Rotation Test

The inverse relationship between headache severity of CGH and ROM towards the most restricted side for the Cervical Flexion-Rotation Test (FRT) was statistically significant for all patients with cervicogenic headaches (Sn = 0.91, Sp = 0.90).[14] The patient should feel no pain at the time of the test. During this test, the neck of the patient is passively held in end range flexion. The therapist rotates the neck to each side until they feel resistance or until the patient says they are in pain. At this end point, the therapist makes a visual estimate of the rotation range and says on which side the FRT was positive or negative. The test was positive when the estimated range was reduced by more than 10° from the anticipated normal range (44°).

- Sudden onset of a new severe headache;

- A worsening pattern of a pre-existing headache in the absence of obvious predisposing factors;

- Headache associated with fever, neck stiff ness, skin rash, and with a history of cancer, HIV, or other systemic illness;

- Headache associated with focal neurologic signs other than typical aura;

- Moderate or severe headache triggered by cough, exertion, or bearing down; and

- New onset of a headache during or following pregnancy.

Patients with one or more red flags should be referred for an immediate medical consultation and further investigation.[14]

Treatment/Management[edit | edit source]

The management of cervicogenic headache is an interprofessional.

- Physical therapy is considered the first line of treatment. Manipulative therapy and therapeutic exercise regimen are effective in treating a cervicogenic headache.

- Another option for treatment of a cervicogenic headache is interventional treatment, which will differ depending on the cause of a headache.

- There is some evidence that cervical epidural steroid injection has some benefits in treating pain in a cervicogenic headache. Steroids can work in this setting due to the theory that the pain continues sensitizing the cervical nerve roots and initiates a pain-producing loop involving nerve root and microvascular inflammation as well as mechanically-induced micro-injury.

- Unfortunately, cervicogenic headaches tend to recur and can significantly affect the quality of life and some patients may also benefit from simultaneous cognitive behavior therapy.[4]

Cervical epidural steroid injections: Indicated for multilevel disc or spine degeneration. There is some evidence that cervical epidural steroid injection has some benefits in treating pain in a cervicogenic headache. Steroids can work in this setting due to the theory that the pain continues sensitizing the cervical nerve roots and initiates a pain-producing loop involving nerve root and microvascular inflammation as well as mechanically-induced micro-injury.[4]

Nerve Blocks: Disrupting the cascade of signals leading to sensitization to central mechanisms via:

- Nerve blocks

- Trigger point injections

- Radiofrequency thermal neurolysis

Other Medications:

- Tricyclic antidepressants - Used at lower dosage than required for pts diagnosed with depression

- Muscle relaxants - Related to the CNS, may be beneficial, evidence is still pending

- Botulinum toxin - A neurotoxin injected into tender muscles to reduce hypertonia

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Although this type of headache is responsive to therapy oriented at treating the soft tissue restrictions, the method of examination, assessment, and treatment needs to be specific to the neck and occiput."[1]

Treatment

- Cervical spine manipulation or mobilization[15] [16]

- Strengthening exercises[15] [16]including deep neck flexors and upper quarter muscles

- Thoracic spine thrust manipulation & exercise[17][16]

- C1-C2 Self-sustained Natural Apophyseal Glide (SNAG)[18] shown to be effective for reducing cervicogenic headache symptoms

Jull et al[9] reported that a six week physiotherapy program including manual therapy and exercise interventions was an effective treatment option for reduction of cervicogenic headache symptoms and decreasing medication intake in both the short term and at one-year follow-up.

According to the Delphi study (2021) conducted to get consensus on physiotherapy treatment in headaches, active mobilisation exercises, upper cervical spine mobilisations, passive mobilisation with movement, work-related ergonomic training, and active mobilisation with movement can be used in the treatment of Cervicogenic headaches.[19]

| [20] | [21] |

| [22] |

Other Treatment Options

Thoracic Manipulation

| Seated CT Manipulation | Seated Mid Thoracic Manipulation |

Re-educating craniocervical spine flexor muscles[edit | edit source]

| Deep Neck Flexor Exercises |

Re-education of craniocervical flexion (CCF) movement[9] The neck flexor muscle synergy is tested with the Cranio‐cervical Flexion Test. The patient palpates the superficial flexors to avoid their inappropriate use. An emphasis on precision and control is essential.

Training the low-level endurance capacity of the deep neck flexors[9] begins as soon as the patient can perform the CCF movement correctly. This phase tests the patient’s ability to hold (approximately 10 seconds) the cranio-cervical flexion position in each stage of the test on repeated occasions. Pressure biofeedback is used to guide training. Training begins at the pressure level that the patient can achieve and hold steady with a good pattern, without dominant use or substitution by the superficial flexor muscles. The patient performs the formal exercise at least twice daily. For each pressure level, the holding time is built up to 10 seconds and 10 repetitions are performed, eventually to the desired level of 30 mm Hg.

Retraining the cervical flexors for antigravity function in sitting position[9] The exercise is a controlled eccentric action of the flexors into cervical extension range followed by a concentric action of these muscles to return the head to the neutral upright position. The return to the upright position must be initiated by CCF, rather than a dominant action of sternocleidomastoid. The exercise is progressed by gradually increasing the range to which the head is moved into extension as control improves, and introducing isometric holds through range.

Extensors of the Craniocervical Spine

The patient practices eccentric control of the head into flexion followed by concentric control back to the neutral position in a 4 point kneeling position to train the coordination of the deep and superficial cervical extensors. These exercises are incorporated with re-education of the scapular muscles in these positions and are commenced early in the program. The exercise is progressed by performing alternating small ranges of craniocervical extension and flexion while maintaining the cervical spine in a neutral position. Co-contraction of the neck flexors and extensors.[9]

Co-contraction of the Neck Flexors and Extensors

The co-contraction is facilitated with rotation and the exercises are introduced once the patient can activate the deep muscles. The patient uses self-resisted isometric rotation in a correct upright sitting posture. They look into the palm of the hand, providing the resistance to facilitate the muscles and perform the alternating rhythmic stabilization exercises with an emphasis on slow onset and slow release holding contractions, using resistance to match about a 10–20% effort. Retraining the strength of the superficial and deep flexor synergy[9]

Retraining the Strength of the Superficial and Deep Flexor Synergy

The head lift must be preceded with CCF followed by cervical flexion to just lift the head from the bed. Gravity and head load provide the resistance. Care must be taken that high load exercise is not introduced too early, as it may be provocative of symptoms.

Retraining the Scapular Muscles

- Retraining scapular orientation in posture[6]A correction strategy is to have the patient move the coracoids upward and the acromion backward, which results in a slight retraction and external rotation of the scapula. The aim is to facilitate the coordinated action of all parts of trapezius and serratus anterior, allowing lower trapezius to slightly depress the medial border of the scapula, consequently lengthening (and relaxing) the levator scapulae. Once the patient learns correct scapular orientation, he repeats the correction and maintains the position regularly throughout the day so that it becomes a habit.

- Training the endurance capacity of the scapular stabilisers[9] Repeated repetitions of 10 second holds of the corrected scapular position encourages early endurance retraining. The endurance of the middle and lower trapezius muscles is also trained by performing an exercise in the prone lying position against the effects of gravity.

- Retraining scapular control with arm movement and load[9] This is important when activities such as computer or deskwork aggravate pain. The patient is encouraged to maintain their newly learned scapular position while performing small range (+/- 60 degrees) arm movements, or during, for example, work at a computer. Scapular control in association with control of cervicothoracic postural position is also trained for functional activities such as lifting and carrying.

Upper Quarter Strengthening Exercises[10]

| Middle Trapezius Strengthening | Lower Trapezius Strengthening |

|

|

Adding upper quarter exercises for patients with cervical dysfunction is important in order to integrate ‘global’ muscles that have connections to the cervical spine through anatomical chains (most notably those connecting the axial and appendicular skeletons).

Re-education of Posture

Posture is an indirect measure of the functional status of the neuromuscular system.[12] Postural position is trained in sitting and is corrected from the pelvis. The second aspect of re-education of postural position is the correction of scapular position. Maintenance of a correct scapular position with appropriate muscle coordination has the added benefit of inducing reciprocal relaxation in muscles such as levator scapulae, which reduces muscular pain in the area.

Sensorimotor Training

Because CGHs are thought to be a dysfunction of the sensorimotor system.[10] Sensorimotor exercises include progressive exercise on unstable surfaces to promote reflexive stabilization and postural stability. Unstable surfaces such as exercise balls or foam pads can be used to add challenge to the cervical spine as well as the whole-body for stabilization exercises. These final stages of the rehabilitation program for CGH patients can be progressed toward functional activities to return the patient to full participation.

Trigger Point Therapy

This is composed of different manual approaches, for example, compression, stretching, or transverse friction massage. Pressure release over the sternocleidomastoid muscle TrP is applied and pressure is progressively applied and increased over the TrP until the finger encountered an increase in tissue resistance (tissue barrier). This pressure is maintained until the therapist sensed a relief of the taut band. At that moment, the pressure is increased again until the next increase in tissue resistance. Do this 3x/session. Stretching of the taut band muscle fibers is also important. This technique has been found to be effective for lengthening the TrP in the muscle and the associated connective tissue. The therapist apply moderate slow pressure over the TrP and slides the fingers in the opposite directions. Trigger point manual therapy is applied slowly and is performed without inducing pain to the patients.[23]

(Myofascial) Mobility, Strength, Stability and Postural Exercices [24]

These technics were primarily postisometric relaxation procedures (A), myofascial mobilization (B) and selected elements of McKenzie therapy (C). Exercises were mainly applied to the muscles with TrPs, showing the pathological increase in rEMG amplitude. When relaxation of painful, tensed muscles is achieved, the next step of treatment include strengthening exercises of the same muscles. All of them are supervised by a physiotherapist. Exercises intensity shall not increase the pain sensation in the cervical spine, shoulder and girdle muscles. They aren’t supposed to evoke the headache. There are isometric exercises with the gradual loading increase (D) and dynamic exercises (E). Elastic therabands are commonly used during these exercises. Additionally, the self-control exercises of the correct body posture are carried out in front of the mirror relying on the visual feedback (F).[24]

Resources[edit | edit source]

Presentations[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Goodman, C, Fuller, K. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2009.

- ↑ Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders.2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2004;24:suppl 1.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 UZ Leuven, Anatomie van de cervicale wervelkolom, 2013. (

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Al Khalili Y, Jain S, Murphy PB. 2019 Headache, Cervicogenic. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507862/ (last accessed 1.2.2020)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Becker WJ. Cervicogenic Headache: Evidence that the neck is a pain generator. Headache. 2010;4 699-705

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Jull G, Stanton W. Predictors of responsiveness to physiotherapy management of cervicogenic headache. Cephalalgia. 2005;25:101-108.

- ↑ Haas M, Spegman A, Peterson D, Aickin M, Vavrek D. Dose response and efficacy of spinal manipulation for chronic cervicogenic headache: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Spine Journal

- ↑ Page P. Cervicogenic headaches: an evidence-led approach to clinical management. International journal of sports physical therapy. 2011 Sep;6(3):254.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9 Jull G, Trott P, Potter H et al., A randomized controlled trial of exercise and manipulative therapy for cervicogenic headache: The cervical therapeutic exercise programme, Spine 2002

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Page P, Cervicogenic headaches: An evidence-led approach to clinical management, The International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, Volume 6, Nr 3, September 2011

- ↑ McDonnell MK et al., A Specific Exercise Program and Modification of Postural Alignment for Treatment of Cervicogenic Headache: A Case Report, J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, Volume 35, Nr 1, January 2005

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Hall T et all. Clinical Evaluation of Cervicogenic Headache: A Clinical Perspective. Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy. 2008;16:73-80.

- ↑ http://ihs-classification.org/en/02_klassifikation/03_teil2/11.02.01_cranial.html (accessed 13 April 2011).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Toby M. Hall, MSc, Kathy Briffa, PhD, Diana Hopper, PhD, and Kim W. Robinson, BSc. The relationship between cervicogenic headache and impairment determined by the flexion-rotation test. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics 2010; Volume 33: Number 9.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Fritz JM, Brennan GP. Preliminary Examination of a Proposed Treatment-Based Classification System for Patients Receiving Physical Therapy Interventions for Neck Pain. Physical Therapy. 2007;87:513-524.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Luedtke, Kerstin, et al. "Efficacy of interventions used by physiotherapists for patients with headache and migraine—systematic review and meta-analysis." Cephalalgia 36.5 (2016): 474-492.

- ↑ Cleland et al. Examination of a Clinical Prediction Rule to Identify Patients with Neck Pain Likely to Benefit from Thoracic Spine Thrust Manipulation and a General Cervical Range of Motion Exercise: Muti-Center Randomized Clinical Trial. Physical Therapy. 2010;90:1239-1253.

- ↑ Hal T et al. Efficacy of a C1-C2 Self-sustained Natural Apophyseal Glide (SNAG) in the Management of Cervicogenic Headache JOSPT 2007;37:100-107.

- ↑ De Pauw R, Dewitte V, de Hertogh W, Cnockaert E, Chys M, Cagnie B. Consensus among musculoskeletal experts for the management of patients with headache by physiotherapists? A delphi study. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice. 2021 Apr 1;52:102325.

- ↑ harrisonvaughanpt. C1-2 Rotatory HVLAT Chin-Hold Technique. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KdFUfVFEb4U [last accessed 24/11/12]

- ↑ OptimumCareProviders. 1.2 Deep Neck Flexor - Longus Colli Strengthening Level 2. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1smVSuQiQx8 [last accessed 09/03/13]

- ↑ ReligiosoPT. Supine Thoracic Thrust. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rj4Y5JGNPZs[last accessed 09/03/13]

- ↑ Gema Bodes-Pardo et al.; Manual treatment for cervicogenic headache and active trigger point in the sternocleidomastoid muscle: a pilot randomized clinical trial; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics Volume 36, Number 7; 2013

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 J. Huber et al.; Reinvestigation of the dysfunction in neck and shoulder girdle muscles as the reason of cervicogenic headache among o ce workers; Disability & Rehabilitation; 2013 May; 35(10): 793-802