Spondylolysis in Young Athletes: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (33 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editors ''' - [[User:Emma Bewick|Emma Bewick]], [[User:James Greenwood|James Greenwood]] and[[User:Matthew Bailey|Matthew Bailey]] | '''Original Editors ''' - [[User:Emma Bewick|Emma Bewick]], [[User:James Greenwood|James Greenwood]] and [[User:Matthew Bailey|Matthew Bailey]] as part of the [[Nottingham University Spinal Rehabilitation Project]]<br> | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} - | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} - | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

= Introduction = | == Introduction == | ||

The young athletic population is at risk of developing low back, particularly spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis. | |||

= | == Spondylolysis == | ||

[[Image:Spondylolysis.jpg|right]][[Spondylolysis]] is defined as a bony defect within the pars interarticularis of the vertebral arch.<ref name="Syrmou">Syrmou, E., Tsitsopoulos, PP., Marinopoulos, D., Tsonidis, C., Anagnostopoulos, I. and Tsitsopoulos, PD. Spondylolysis: A review and a reappraisal. Hippokratia. 2010;14(1):17-2.</ref> It presents as a weakness or fracture at this point. The vast majority of spondylotic defects are seen at level L5 (85-95%), with level L4 being the sec<span style="line-height: 1.5em;">ond most likely to be affected -the higher levels of the lumbar spine are rarely affected</span><ref name=":1">Debnath UK. [https://orthosurgeonujjwal.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/LumbarSpondylolysis_CCR_Jul2021.pdf Lumbar spondylolysis-Current concepts review]. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma. 2021 Oct 1;21:101535.</ref>. | |||

Spondylolysis is defined as a bony defect within the pars interarticularis of the vertebral arch. | |||

[ | |||

== Spondylolisthesis == | == Spondylolisthesis == | ||

[[Image:Spondylolisthesis presentation.jpg|right]][[Spondylolisthesis|Spondylolisthesis]] is the forward shift of one vertebra on another. The slip usually occurs anteriorly at the levels of L5/S1 and causes the vertebra to move out of alignment with the other spinal vertebrae. This often occurs as a result of a bilateral spondylolysis,<ref name="Luqmani">Luqmani, R., Robb, J., Porter, D. and Keating, J. Textbook of Orthopaedics, Trauma and Rheumatology. China: Elsevier Limited, 2008.</ref> with it being reported that 50-81% of these cases develop a spondylolisthesis. However, this may also occur as a result of birth defects, trauma or degeneration<ref name="Krabak">Krabak, BJ., Carter, CT. Sports Medicine: Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics. North America: Clinical Review Articles Elsevier Health Sciences, 2014. </ref> | |||

The degree of slip can be graded using the Meyerding scale. A first-degree injury involves a slippage of 0-25% of the diameter. A second-degree slip is 25-50% and a third-degree is 50-75%. This can progress to a fourth-degree slippage which would be a 75-100% diameter displacement or the vertebrae can displace by more than 100% producing a grade 5 slip.<ref name="Krabak" /> | |||

== Epidemiology/Etiology == | |||

= Epidemiology/Etiology = | |||

It is | It is estimated that spondylolysis is present in 6 – 8% of the general population.<ref name=":1" /> The incidence and prevalence is much higher in the young athletic population, estimated to be 15-47% and 7-21% respectively. <ref name=":1" /><ref name=":0">Selhorst M, Allen M, McHugh R, MacDonald J. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7134351/ Rehabilitation considerations for spondylolysis in the youth athlete. International journal of sports physical therapy.] 2020 Apr;15(2):287.</ref> In symptomatic young athletes, spondylolysis accounts for 14-30% of cases<ref name=":0" />. There is a particular increased risk in sports which subject athletes to [[Lumbar Spondylolysis in Extension Related Sport|repetitive hyperextension]] and rotation across the lumbar spine.<ref name=":0" /> Baseball, cricket, diving, gymnastics, soccer, wrestling and weightlifting have been identified as sports that pose a higher risk for spondylolysis.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

The exact cause of spondylolysis currently remains unclear, with many factors thought to contribute to its development.<ref name="McCleary2007">McCleary, M. D. and Congeni, J. A. Current concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of spondylolysis in young athletes. Current sports medicine reports. 2007; 6(1): 62-66.</ref> It has been described as hereditary, or acquired as a result of repetitive stress to the lumbar spine.<ref name="Haun">Haun D.W. and Kettner, N. W. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: a narrative review of etiology, diagnosis, and conservative management. Journal of chiropractic medicine 2006: 4(4); 206-217.</ref> In the young athlete the spine is still growing, giving rise to numerous ossification centres which leave points of weakness in the spine.<ref name="McCleary2007" /><ref name=":1" /> This leaves young athletes, in particular those exposed to repetitive hyperextension and rotation of the lumbar spine, susceptible to injury and the development of spondylolysis. | |||

== Clinical Presentation == | |||

Majority of the cases are '''asymptomatic'''<ref name=":2">Lawrence KJ, Elser T, Stromberg R. Lumbar spondylolysis in the adolescent athlete. Physical Therapy in Sport. 2016 Jul 1;20:56-60.</ref>'''.''' Incidental findings of spondylolysis in a asymptomatic individual should not warrant treatment.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

== | === Subjective Assessment === | ||

* Can be acute or gradual onset of pain - often described as a dull ache that becomes sharp with movement<ref name="Litao">Litao, A., Munyak, J., Perron, AD., Talavera, F., Goitz, HT., Whitehurst, JB. and Young, C. Lumbrosacral Spondylolysis Clinical Presentation MedScape. 2013. Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/95691-clinical#showall</ref> | |||

* Pain worsens with activity, especially with lumbar extension movements<ref name=":0" /> - May be worse after intensive repetitive athletic activity (hyperextension or rotation) eg. Cricket, gymnastics, weightlifting, track and field athletes, tennis and rowing<ref name=":2" /> | |||

* May report recent history of trauma to that area, but often insidious onset<ref name=":0" /> | |||

* Radiating pain to the legs is uncommon<ref name=":0" /> | |||

* Rest eases symptoms | |||

=== Objective Assessment === | |||

* Tenderness on palpation of the spinous process of the affected vertebra<ref name=":2" /> | |||

* Reproduction of pain during one legged hyperextension manoeuvre - not very sensitive or specific<ref>Alqarni, A., Schneiders, A., Cook, C. and Hendrick, P. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1466853X15000024/pdf?crasolve=1&r=7df532480c2b06fb&ts=1688115390737&rtype=https&vrr=UKN&redir=UKN&redir_fr=UKN&redir_arc=UKN&vhash=UKN&host=d3d3LnNjaWVuY2VkaXJlY3QuY29t&tsoh=d3d3LnNjaWVuY2VkaXJlY3QuY29t&rh=d3d3LnNjaWVuY2VkaXJlY3QuY29t&re=X2JsYW5rXw%3D%3D&ns_h=d3d3LnNjaWVuY2VkaXJlY3QuY29t&ns_e=X2JsYW5rXw%3D%3D&rh_fd=rrr)n%5Ed%60i%5E%60_dm%60%5Eo)%5Ejh&tsoh_fd=rrr)n%5Ed%60i%5E%60_dm%60%5Eo)%5Ejh&iv=0a4fd9b0a51e4c066f5d4675c2de435a&token=65643936306631343566653831313831306636396339646462643638323361356432616233333538323962636632666662396634636636326665363933613766323639636663323662306164346336316337643339636665363431613a653936663532353539313166336438383462616634666633&text=760ccc413c019779d9abbfd01a462db5f311930022f378662108386bfd7c297afc7d63d4314c3cbaf9fa2210d8f119a1877d99742f3ddb974a75f514c846715caa7d503d496e91e01323324f4722e4aeececeb3daaa5ab3c83c134d6307a50d560c1cb7d012350d0910838cff67370ddcaec42942ce14e39487306946ec56d00e5dcaadd4f22fabd0a912036ac37741e8811ebc124fd29faa61c6ea5065d5d13a3c3ee33ee5e9a6d606aa3fb3a7338f493b8cb396f3aa2728ccde7324fde77deebb12ecab9b180dbee981829a08382751cf6fd3cd776de3ab08c847e3b606175d8324b7e4017e5f8d358c9c522ff48b4b46a1359e64ee13738b23e1d78af5a5ae6aeba6f4d9307deb891db8ab81b968b01c551e5bfbe56fe2e22de82b60725eb5824805855f5ff09a8a14ca79ec290cc&original=3f Clinical tests to diagnose lumbar spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis:] A systematic review. Physical Therapy in Sport. 2015; 16(3), pp.268-275.</ref> | |||

* Flexion does not often cause pain and range of movement often full | |||

* Neurological assessment should be normal unless an additional pathology is present - sciatica may occur but is rare | |||

* Muscle guarding either unilateral or bilateral erector spinae | |||

* Hyperlordotic posture or flattening of the lumbar spine<ref name=":2" /> | |||

* Tight hamstrings and hip flexors<ref name=":0" /><br> | |||

== Differential Diagnosis == | |||

For a list of differential diagnoses [[Spondylolysis|click here.]] | |||

== Diagnosis Procedures == | |||

Early diagnosis has been found to increase the likelihood of healing.<ref name="Sundell2013">Sundell, CG., Jonsson, H., Adin, L. and Larsen, KH. Clinical Examination, Spondylolysis and Adolescent Athletes International Journal of Sports Medicine. 2013; 34(3): 263-267</ref> Definitive diagnosis can however be a challenge as clinical tests have little value and the he most appropriate form of diagnostic imaging has not yet been clearly established.<ref name=":0" /> A combination of various methods may be the most reliable. | |||

=== Diagnostic Imaging === | |||

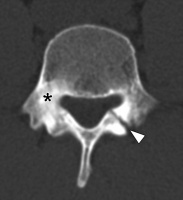

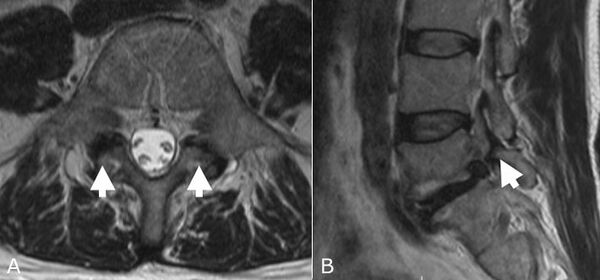

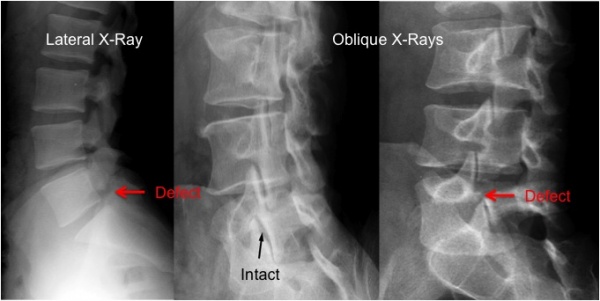

CT scans, SPECT scans and MRI have all been found to be sensitive diagnostic tools for spondylolysis.<ref name="Masci">Masci, L., Pike, J., Malara, F., Phillips, B., Bennell, K. & Brukner, P. Use of one-legged hyperextension test and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of active spondylolysis British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2006; 40(11): 940-946.</ref> It is however important to consider the amount of radiation exposure in adolescents. For more information on diagnostic imaging visit [[Lumbar Spondylolysis in Extension Related Sport]]. | |||

== | * '''X-rays:''' Only 30-38% of spondolytic defects are seen on X-ray (very low sensitivity)<ref name="Watkins">Watkins IV, RG. & Watkins III, RG. Lumbar Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis in Athletes Seminars in Spine Surgery. 2010; 22(4): 210-217</ref>. The oblique view is the most useful, but results in more radiation. Plain radiography may assist in identifying any extreme bony abnormalities including spondylolisthesis.<ref name="McClearyandCongeni">McCleary, M. D. and Congeni, J. A. Current concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of spondylolysis in young athletes. Current sports medicine reports. 2007; 6(1): 62-66.</ref> | ||

* '''Computed Tomography''' (CT): CT scans have been found to be quite sensitive for detecting lesions, but comes with high levels of radiation exposure<ref name=":0" /> | |||

* '''Single Photon Emission Computerised Tomography (SPECT):''' is quite sensitive for detecting spondylolysis, but its use in clinical practice has declined<ref name=":1" /> | |||

* '''Magnetic Resonance Imaging [[MRI Scans|(MRI)]]:''' can be used to identify varying pathologies associated with low back pain (See Differential Diagnosis section). MRI has been advocated as an alternative to CT and SPECT and is often considered more appealing because of its non-ionising properties <span style="line-height: 1.5em;">and found to have no statistical difference with the CT findings.</span><ref name="Masci" /> | |||

<div class="row"> | |||

<div class="col-md-4">[[Image:Spondylolysis CT scan (1).docx.jpg|center|400x200px|thumb|CT-Scan]] </div> | |||

<div class="col-md-4">[[Image:MRI image Spondylolysis.jpg|center|600x400px|thumb|MRI-Scan]]</div> | |||

<div class="col-md-4">[[Image:Spondylolysis x ray .docx.jpg|center|600x400px|thumb|X-ray indicating pars interarticularis defect]]</div> | |||

</div> | |||

It has been argued that imaging may not be necessary as it rarely changes the management of spondylolysis. The following patient characteristics can assist with '''ruling out spondylolysis''' without imaging (if 2/3 are absent, there is 88% sensitivity to help rule out active spondylolysis<ref>Therriault T, Rospert A, Selhorst M, Fischer A. Development of a preliminary multivariable diagnostic prediction model for identifying active spondylolysis in young athletes with low back pain. Physical Therapy in Sport. 2020 Sep 1;45:1-6.</ref>: | |||

< | # Male sex | ||

# Pain with extension | |||

# Difference between active and resting pain | |||

In cases where it can't be ruled out, Tofte et al. suggests using two-view x-rays as an initial stidy, followed by MRI in early diagnosis or CT in cases of more persistent low back pain<ref>Tofte JN, CarlLee TL, Holte AJ, Sitton SE, Weinstein SL. [https://upload.orthobullets.com/journalclub/free_pdf/27669047_8.%20Tofte,%20SPINE%202017%20-%20Imaging%20Pediatric%20Spondylolysis.pdf Imaging pediatric spondylolysis: a systematic review.] Spine. 2017 May 15;42(10):777-82.</ref> | |||

[[Image: | === One Legged Hyperextension Manoeuvre === | ||

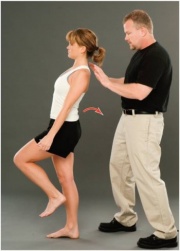

[[Image:One legged hyperextension.jpg|One leg hyperextension test|alt=Demonstration of one leg hyperextension manoeuvre|251x251px|right|frameless]] | |||

= | * Patient stands on one leg and leans backwards | ||

* Unilateral lesions may cause pain when performed on ipsilateral leg | |||

* May cause reproduction of pain either unilaterally or bilaterally | |||

* Masci et al. <ref name="Masci" /> found that the one-legged hyperextension manoeuvre was neither specific nor sensitive in detecting spondylolysis. The manoeuvre may detect an abnormality in the posterior structures but should not be relied upon to make the diagnosis. | |||

== Outcome Measures == | |||

* [[Roland‐Morris Disability Questionnaire|Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire]] | |||

* [[Oswestry Disability Index]] | |||

* Micheli Functional Scale - most appropriate for higher functioning populations | |||

== | == Spondylolysis in Sport == | ||

High incidence rates of spondylolysis have been reported in a number of sports including cricket, gymnastics, tennis and weightlifting. Therefore this section will briefly touch upon some of these sports and why these young athletes are more predisposed to this condition. See also [[Lumbar Spondylolysis in Extension Related Sport]]. | |||

=== Cricket === | |||

[[File:Cricket.jpg|thumb|Fast Bowler]] | |||

A 2002 study observed bowlers over 6 months; they found that 10% of spin bowlers and 12% of fast bowlers developed low back pain over the season.<ref name="Gregory">Gregory, P. L., Batt, M. E., & Wallace, W. A. Comparing injuries of spin bowling with fast bowling in young cricketers. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine.2002; 12(2):107-112.</ref> The action of bowling in cricket involves rotation and side flexion of the spine at high speeds. As the front leg comes forward to deliver the ball, forces travelling through the leg and up into the lumbar spine can be 3-9 times that of our body weight. Studies believe that young cricketers are more at risk due to longer and more intense training sessions, poor preparation and technique, longer spells of bowling and subsequently overuse.<br><br>Treatment for this population can be difficult as it often involves rest in the early stages - this can be as long as 8 months in some cases. However it is then important to address factors such as muscle imbalance, core stability, flexibility and pelvic control. Although they will be unable to bowl during this period of time they can continue to maintain cardiovascular fitness. Most importantly treatment must be sport specific especially in the later stages of rehab<ref name="Becker">Becker, C. Lumbar Spondylolysis: Diagnosis and Rehabilitation. Sport Ex Journal. 2006;30:6-9.</ref>. | |||

< | === Gymnastics === | ||

[[Image:Gymnast .jpg|300x300px|Gymnast performing on the beam|right]]It was reported in a paper published in 2000<ref name="Guillodo">Guillodo, Y., Botton, E., Saraux, A., & Le Goff, P. Contralateral spondylolysis and fracture of the lumbar pedicle in an elite female gymnast: a case report. Spine. 2000;25(19): 2541-2543.</ref> that the incidence rate of spondylolysis in gymnasts was between 15-20% - this is much higher than the general population. It is not hard to understand why this would be due to the high physical demands of the sport, the hours of daily training and repetitive forces.<ref name="Kruse">Kruse, D. and Lemmen, B. Spine injuries in the sport of gymnastics. Current sports medicine reports. 2009;8(1): 20-28.</ref>Along with these forces, athletes are put into positions such as hyperextension which puts a great amount of pressure on the posterior aspects of the lumbar vertebra, e.g. when performing a flip or when trying to maintain a specific pose. Athletes are also forced into hyperextension when vaulting and landing, applying excessive stress on the vertebra . | |||

=== Weightlifting === | |||

This is another high intensity sport, which involves increased forces. The incidence rate of spondylolysis has been reported to be between 30.7-44%. <ref name="Stone">Stone, M. H., Fry, A. C., Ritchie, M., Stoessel-Ross, L., & Marsit, J. L. Injury potential and safety aspects of weightlifting movements. Strength and Conditioning Journal. 1994; 16(3): 15-21.</ref> Studies believe there is a clear relationship between this condition and the stress of lifting. Stone et al.<ref name="Stone" /> described the actions involved in weightlifting and discussed the excessive impact forces seen during the catching phase of the bar. They also noted that these stress and shear forces are greatly increased through the joints when the athlete completes the jump onto one leg. | |||

== Management/Interventions == | |||

Enabling patients to return to sport is at the forefront of any treatment plan for an athlete following injury. Each athlete must be considered individually in terms of his/her symptoms, functional limitations, their sport and level of participation, as well as any other characteristics which may influence their treatment.<ref name="StandaertandHerring2007">Standaert, CJ & Herring SA. Expert Opinion and Controversies in Sports and Musculoskeletal Medicine: A Diagnosis and Treatment of Spondylolysis in Adolescent Athletes Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2007; 88(4): 537-540.</ref> | |||

< | The optimal treatment for athletes with spondylolysis is still widely debated within the literature, with a lack of controlled studies investigating management.<ref name="Syrmou" /> However it is generally accepted that the young athlete with spondylolysis should initially be managed conservatively.<ref name="McNeely">McNeely, M. L., Torrance, G. and Magee, D. J. A systematic review of physiotherapy for spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Manual therapy. 2003; 8(2), 80-91.</ref> Surgical management is generally only considered when all conservative methods have failed, with only an estimated 9-15% of all symptomatic cases undergoing surgery.<ref name="Syrmou" /> | ||

=== <span style="font-size: 20px; line-height: 1.5em; background-color: initial;">Conservative Management</span> === | |||

Conservative treatment is generally the initial management plan for young athletes with spondylolysis<ref name=":0" />. Following conservative management, 92% of individuals are able to return to sport within 6 months.<ref name=":0" /> Physiotherapy with these patients aims to restore range of motion, stabilise and strengthen the spine, and to reduce pain. The goal of management should not be focused on radiographic bony healing. Not all lesions heal and bony healing is not associated with quality of life or ability to return to sport.<ref name=":0" />Repeat imaging is therefore not indicated and clinical decision making should rather be based on functional parameters<ref name=":0" />. | |||

The most common components of a conservative management plan include:<ref name="McNeely" /><ref name=":1" /> | |||

< | * '''Rest from activity -'''cessation of sport activity is recommended for at least 3 months<ref name=":0" /> | ||

* Lumbosacral '''bracing''' | |||

* '''Strengthening''' of: the core, pelvic floor, gluteals, spinal stabilisers and extensors, quadratus lumborum | |||

* '''Stretching''' of the hip flexors and hamstrings | |||

==== Bracing ==== | |||

The use and effectiveness of lumbosacral braces is still debated within the literature. The rationale behind bracing is to allow the healing of the bony defect in the pars interarticularis. Further research is necessary to establish its effectiveness - until then it may be recommended in cases that fail to improve with rest alone<ref name=":0" /> | |||

==== Physiotherapy ==== | |||

The optimal time to start with physiotherapy is still debated, but research suggest that starting earlier may lead to earlier return to sport.<ref name=":0" /> Physiotherapy should focus on: | |||

* '''Lumbar stability exercises:''' exercises targeting the deep abdominals and multifidus has been shown to be superior to general exercise.<ref name=":0" /> Watkins describes how strengthening these muscles will provide biomechanically sound spinal function to allow a return to sport<ref name="Watkins" /> | |||

* '''Sport Specific Exercises:''' It is important that core stability strengthening is progressed into functional, specific exercises for each athlete following the initial period of retraining/activating the core muscles.<ref name="Watkins" /> For example, in cricket, when focusing on core stability the player is standing on one leg balancing on a soft cushion or trampette while performing the bowling action. This is later progressed by attaching the ball to an elastic band, which is tied to a fixed point behind the player<ref name="Becker" />. | |||

* '''Motor control training:''' Trunk coordination exercises and dynamic lumbar strengthening<ref name=":0" /> | |||

< | Manipulation and Electrotherapy is not recommended as treatment modalities for spondylolysis<ref name=":0" />. Any modalities used for pain relief, it should be sued with the goal of promoting exercise and activity. | ||

===== Treatment framework proposed by Selhorst et al (2020) <ref name=":0" />: ===== | |||

For a more detailed description and criteria for advancing to the next phase, you can read the article [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7134351/pdf/ijspt-15-287.pdf here]. For more detail on core strengthening see [[Core Strengthening]] and the [[The PGM Method - Activating the Core, Targeted Strengthening and Stretching for the Pelvic Girdle|PGM Method]] | |||

| | |||

====== '''Phase 1 - Isolated''' ====== | |||

[[File:Static core positions.png|thumb|Static Core Positions]] | |||

Static and neutral lumbar position during exercises - allows muscle activation while avoiding stress on the injured pars interarticularis. | |||

* Patient education to minimise fear of movement and to encourage participation in ADLs | |||

* Target the deep abdominals and multifidus - static spine while performing extremity movements | |||

* Address limitations in flexibility in the upper and lower limb as needed (while maintaining a neutral spine) - especially hip flexors and hamstrings | |||

====== '''Phase 2 - integrated''' ====== | |||

As symptoms improve, start to include extension and rotation movements. Although these movements, when performed repetitively and at end-range, place stress on the pars interarticularis, they are still functional movements and are safe when performed in a controlled manner. Progressive restoration of these movements are essential for return to sport. | |||

* Balance and dynamic activities | |||

* Progress endurance of stabilisers - stabilisation during spinal movement and core control in upright positions | |||

====== '''Phase 3 - return to sport''' ====== | |||

Address impairments in other regions of the body, as these may increase stress throughout the lumbar spine and should be addressed. | |||

* Sport specific strength and endurance | |||

* Muscle control during sport specific activities | |||

* Graded return to sport | |||

=== Surgical Interventions === | |||

The use of surgery for spondylolysis within the young athletic population is seen as a last resort option, after all the methods of conservative treatment fail.<ref name="Syrmou" /> There are vast arrays of surgical techniques which can be performed, but most commonly either a screw or wire fixation are the preferred methods.<ref name="Drazin">Drazin D., Shirzadi A., Jeswani S., Ching H., Rosner J., Rasouli A. et al. Direct surgical repair of spondylolysis in athletes: indications, techniques, and outcomes. Neurosurgical focus. 2011: 31(5); E9.</ref> | The use of surgery for spondylolysis within the young athletic population is seen as a last resort option, after all the methods of conservative treatment fail.<ref name="Syrmou" /> There are vast arrays of surgical techniques which can be performed, but most commonly either a screw or wire fixation are the preferred methods.<ref name="Drazin">Drazin D., Shirzadi A., Jeswani S., Ching H., Rosner J., Rasouli A. et al. Direct surgical repair of spondylolysis in athletes: indications, techniques, and outcomes. Neurosurgical focus. 2011: 31(5); E9.</ref> | ||

Surgery has a high success rate in the young athletic population and has been shown to be very effective in returning athletes to their sport.<ref name="Debnath">Debnath, U. K., Freeman, B. J. C., Gregory, P., de la Harpe, D., Kerslake, R. W. and Webb, J. K. Clinical outcome and return to sport after the surgical treatment of spondylolysis in young athletes. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, British. 2003;Volume, 85(2), 244-249.</ref> However, in comparison to the conservative approach, surgical treatment did require athletes to have an extended period away from their sport. One study showed an average lay off time of 7 months following surgical treatment.<ref name="Debnath" /> Due the nature of surgery, athletes still require a period of rehabilitation postoperatively.<ref name="Drazin" /> This post operative treatment will include many of the exercises used in the conservative approach, targeting the strengthening of core stability muscles.<ref name="Drazin" /> | |||

== Biopsychosocial Factors == | |||

Sports injuries can have major impacts on an athlete’s career. Some injuries can even terminate their future ability to perform. Psychological issues may impact the rehabilitation of an injured athlete. It is therefore important that an athlete’s rehabilitation programme includes a component that addresses psychological factors. This will in turn aid physical recovery, prevent re-injury, promote return to sport and increase adherence to rehabilitation.<ref name="Schwab">Schwab Reese, LM., Pittsinger, R. and Wang, J. Effectiveness of psychological intervention following sport injury Journal of Sport and Health Science. 2012; 1(2): 71-79.</ref> | |||

= | |||

Sports injuries can have major impacts on an athlete’s career. Some injuries can even terminate their future ability to perform. Psychological issues may impact the rehabilitation of an injured athlete. | |||

It is therefore important that an athlete’s rehabilitation programme includes a component that addresses | |||

The [[Biopsychosocial Model|biopsychosocial model]] proposed by Brewer et al. <ref name="Brewer2002">Brewer, BW., Anderson, MB. & Van Raalte, JI. Psychological Aspects of Sport Injury Rehabilitation: Toward a Biopsychosocial Approach Medical and Psychological Aspects of Sport and Exercise 41-54 D. Morgantown: WV Fitness Information Technology. 2002.</ref> shows how psychological and social factors have an impact on injury rehabilitation. The model was designed to widen the focus of rehabilitation. The model shows how characteristics of injury, sociodemographic factors, biological factors, immediate biological outcomes, social factors and psychological factors all affect the sport rehabilitation outcomes. | |||

[[File:Biopsychosocial_Model.png|thumb|444x444px|Schematic diagram of the biopsychosocial model]] | |||

Injured athletes often experience emotional distress - including decreased self-esteem, anxiety, frustration, isolation and depression.<ref name=":0" /> . Therefore, injury can have a great impact on their mental well-being.<br>'''Fear''' can have a huge impact on recovery and return to sport. Many athletes become fearful of re-injury leading to them not training at full intensity. This may also have an impact on adherence to rehabilitation. | |||

Not all athletes suffer from emotional distress post-injury. Self-efficacy, self-esteem, confidence and motivation prior to injury are some factors in particular that can be used to determine an athlete’s reaction post-injury.<ref name="Wagman">Wagman, D. and Khelifa, M. Psychological Issues in Sport Injury Rehabilitation: Current Knowledge and Practice Journal of Athletic Training. 1996; 31(3): 257-26.</ref> | |||

These factors need to be taken into consideration when communicating with athletes, and can be addressed through strategies such as emotional support, active listening, reality confirmation and positive support<ref name=":0" />. Counselling can be used to target psychological barriers that may affect an athlete’s return to sport and focus on this specifically. In severe cases of depression, referral to a psychologist may be necessary. | |||

=== Patient Testimonial === | |||

Kamal is a 21 year old, cricket player, playing at a competitive University level. He was diagnosed with Spondylolysis 5 years ago. and was treated conservatively with physiotherapy. In his testimony, made by ourselves, Kamal talks about his experiences, treatment, and emotional well being, as a young athlete with spondylolsis. {{#ev:youtube|umP11yb7B5E}} | |||

== Role of the MDT == | |||

The MDT team of an injured athlete would often involve a medical practitioner, coach, physiotherapist and psychologist. Prognosis and realistic time frames need to be well communicated and consistent among team members. | |||

Accurate, non-threatening communication is of vital importance by all team members. Using the wrong language can instil fear in athletes as they perceive their back to be 'broken'. This can increase fear of activity and re-injury<ref name=":0" />. Exaggerated perceptions need to be met with improved language ('bone stress injury' instead of 'broken') and reassurance relating to the good prognosis and positive outcomes seen in athletes.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

== Case Study == | |||

'''This account was taken from a physiotherapist working in an outpatients setting. The case study describes a past patient that she assessed and treated'''. | '''This account was taken from a physiotherapist working in an outpatients setting. The case study describes a past patient that she assessed and treated'''. | ||

| Line 302: | Line 182: | ||

The patient was then instructed to completely rest for the next four months, he was referred back for physiotherapy at this point. Now, on examination, his movements were pain-free. On palpation there was some mild stiffness in the low lumbar spine but the hip and straight leg raise showed no symptoms. Treatment at this point included gentle stability and strengthening exercises. <br>For example he was encouraged to stretch his hamstrings, use breathing control and begin lower transverse abdominal exercises: spine curls in lying, bridging exercises and stability exercises whilst moving the legs. | The patient was then instructed to completely rest for the next four months, he was referred back for physiotherapy at this point. Now, on examination, his movements were pain-free. On palpation there was some mild stiffness in the low lumbar spine but the hip and straight leg raise showed no symptoms. Treatment at this point included gentle stability and strengthening exercises. <br>For example he was encouraged to stretch his hamstrings, use breathing control and begin lower transverse abdominal exercises: spine curls in lying, bridging exercises and stability exercises whilst moving the legs. | ||

These were later progressed onto the Swiss Ball combined with more functional exercises in standing aiming towards cricket related exercises. For example using the overhead movement of the arm taking care not to over extend the lumbar spine. Ensuring there wasn't a hinge point into lumber extension and that rotation was used. It was also worth checking he had enough available shoulder movement. <br> | These were later progressed onto the Swiss Ball combined with more functional exercises in standing aiming towards cricket related exercises. For example using the overhead movement of the arm taking care not to over extend the lumbar spine. Ensuring there wasn't a hinge point into lumber extension and that rotation was used. It was also worth checking he had enough available shoulder movement. <br> | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> <br> | ||

[[Category:Nottingham University Spinal Rehabilitation Project]] | |||

[[Category:Lumbar Spine - Conditions]] | |||

[[Category:Lumbar Spine]] | |||

[[Category: | [[Category:Sports_Injuries]] | ||

[[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics]] | |||

[[Category:Sports Medicine]] | |||

[[Category:Younger Athlete]] | |||

[[Category:Occupational Health]] | |||

[[Category:Paediatrics]] | |||

[[Category:Conditions]] | |||

[[Category:Paediatrics - Conditions]] | |||

Latest revision as of 11:08, 30 June 2023

Original Editors - Emma Bewick, James Greenwood and Matthew Bailey as part of the Nottingham University Spinal Rehabilitation Project

Top Contributors - Matthew Bailey, James Greenwood, Laura Ritchie, Emma Bewick, Melissa Coetsee, Kim Jackson, Lucy Baxter, Wanda van Niekerk, 127.0.0.1, Evan Thomas, Naomi O'Reilly, Candace Goh, Amrita Patro and Tolulope Adeniji -

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The young athletic population is at risk of developing low back, particularly spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis.

Spondylolysis[edit | edit source]

Spondylolysis is defined as a bony defect within the pars interarticularis of the vertebral arch.[1] It presents as a weakness or fracture at this point. The vast majority of spondylotic defects are seen at level L5 (85-95%), with level L4 being the second most likely to be affected -the higher levels of the lumbar spine are rarely affected[2].

Spondylolisthesis[edit | edit source]

Spondylolisthesis is the forward shift of one vertebra on another. The slip usually occurs anteriorly at the levels of L5/S1 and causes the vertebra to move out of alignment with the other spinal vertebrae. This often occurs as a result of a bilateral spondylolysis,[3] with it being reported that 50-81% of these cases develop a spondylolisthesis. However, this may also occur as a result of birth defects, trauma or degeneration[4]

The degree of slip can be graded using the Meyerding scale. A first-degree injury involves a slippage of 0-25% of the diameter. A second-degree slip is 25-50% and a third-degree is 50-75%. This can progress to a fourth-degree slippage which would be a 75-100% diameter displacement or the vertebrae can displace by more than 100% producing a grade 5 slip.[4]

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

It is estimated that spondylolysis is present in 6 – 8% of the general population.[2] The incidence and prevalence is much higher in the young athletic population, estimated to be 15-47% and 7-21% respectively. [2][5] In symptomatic young athletes, spondylolysis accounts for 14-30% of cases[5]. There is a particular increased risk in sports which subject athletes to repetitive hyperextension and rotation across the lumbar spine.[5] Baseball, cricket, diving, gymnastics, soccer, wrestling and weightlifting have been identified as sports that pose a higher risk for spondylolysis.[5]

The exact cause of spondylolysis currently remains unclear, with many factors thought to contribute to its development.[6] It has been described as hereditary, or acquired as a result of repetitive stress to the lumbar spine.[7] In the young athlete the spine is still growing, giving rise to numerous ossification centres which leave points of weakness in the spine.[6][2] This leaves young athletes, in particular those exposed to repetitive hyperextension and rotation of the lumbar spine, susceptible to injury and the development of spondylolysis.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Majority of the cases are asymptomatic[8]. Incidental findings of spondylolysis in a asymptomatic individual should not warrant treatment.[5]

Subjective Assessment[edit | edit source]

- Can be acute or gradual onset of pain - often described as a dull ache that becomes sharp with movement[9]

- Pain worsens with activity, especially with lumbar extension movements[5] - May be worse after intensive repetitive athletic activity (hyperextension or rotation) eg. Cricket, gymnastics, weightlifting, track and field athletes, tennis and rowing[8]

- May report recent history of trauma to that area, but often insidious onset[5]

- Radiating pain to the legs is uncommon[5]

- Rest eases symptoms

Objective Assessment[edit | edit source]

- Tenderness on palpation of the spinous process of the affected vertebra[8]

- Reproduction of pain during one legged hyperextension manoeuvre - not very sensitive or specific[10]

- Flexion does not often cause pain and range of movement often full

- Neurological assessment should be normal unless an additional pathology is present - sciatica may occur but is rare

- Muscle guarding either unilateral or bilateral erector spinae

- Hyperlordotic posture or flattening of the lumbar spine[8]

- Tight hamstrings and hip flexors[5]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

For a list of differential diagnoses click here.

Diagnosis Procedures[edit | edit source]

Early diagnosis has been found to increase the likelihood of healing.[11] Definitive diagnosis can however be a challenge as clinical tests have little value and the he most appropriate form of diagnostic imaging has not yet been clearly established.[5] A combination of various methods may be the most reliable.

Diagnostic Imaging[edit | edit source]

CT scans, SPECT scans and MRI have all been found to be sensitive diagnostic tools for spondylolysis.[12] It is however important to consider the amount of radiation exposure in adolescents. For more information on diagnostic imaging visit Lumbar Spondylolysis in Extension Related Sport.

- X-rays: Only 30-38% of spondolytic defects are seen on X-ray (very low sensitivity)[13]. The oblique view is the most useful, but results in more radiation. Plain radiography may assist in identifying any extreme bony abnormalities including spondylolisthesis.[14]

- Computed Tomography (CT): CT scans have been found to be quite sensitive for detecting lesions, but comes with high levels of radiation exposure[5]

- Single Photon Emission Computerised Tomography (SPECT): is quite sensitive for detecting spondylolysis, but its use in clinical practice has declined[2]

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): can be used to identify varying pathologies associated with low back pain (See Differential Diagnosis section). MRI has been advocated as an alternative to CT and SPECT and is often considered more appealing because of its non-ionising properties and found to have no statistical difference with the CT findings.[12]

It has been argued that imaging may not be necessary as it rarely changes the management of spondylolysis. The following patient characteristics can assist with ruling out spondylolysis without imaging (if 2/3 are absent, there is 88% sensitivity to help rule out active spondylolysis[15]:

- Male sex

- Pain with extension

- Difference between active and resting pain

In cases where it can't be ruled out, Tofte et al. suggests using two-view x-rays as an initial stidy, followed by MRI in early diagnosis or CT in cases of more persistent low back pain[16]

One Legged Hyperextension Manoeuvre[edit | edit source]

- Patient stands on one leg and leans backwards

- Unilateral lesions may cause pain when performed on ipsilateral leg

- May cause reproduction of pain either unilaterally or bilaterally

- Masci et al. [12] found that the one-legged hyperextension manoeuvre was neither specific nor sensitive in detecting spondylolysis. The manoeuvre may detect an abnormality in the posterior structures but should not be relied upon to make the diagnosis.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire

- Oswestry Disability Index

- Micheli Functional Scale - most appropriate for higher functioning populations

Spondylolysis in Sport[edit | edit source]

High incidence rates of spondylolysis have been reported in a number of sports including cricket, gymnastics, tennis and weightlifting. Therefore this section will briefly touch upon some of these sports and why these young athletes are more predisposed to this condition. See also Lumbar Spondylolysis in Extension Related Sport.

Cricket[edit | edit source]

A 2002 study observed bowlers over 6 months; they found that 10% of spin bowlers and 12% of fast bowlers developed low back pain over the season.[17] The action of bowling in cricket involves rotation and side flexion of the spine at high speeds. As the front leg comes forward to deliver the ball, forces travelling through the leg and up into the lumbar spine can be 3-9 times that of our body weight. Studies believe that young cricketers are more at risk due to longer and more intense training sessions, poor preparation and technique, longer spells of bowling and subsequently overuse.

Treatment for this population can be difficult as it often involves rest in the early stages - this can be as long as 8 months in some cases. However it is then important to address factors such as muscle imbalance, core stability, flexibility and pelvic control. Although they will be unable to bowl during this period of time they can continue to maintain cardiovascular fitness. Most importantly treatment must be sport specific especially in the later stages of rehab[18].

Gymnastics[edit | edit source]

It was reported in a paper published in 2000[19] that the incidence rate of spondylolysis in gymnasts was between 15-20% - this is much higher than the general population. It is not hard to understand why this would be due to the high physical demands of the sport, the hours of daily training and repetitive forces.[20]Along with these forces, athletes are put into positions such as hyperextension which puts a great amount of pressure on the posterior aspects of the lumbar vertebra, e.g. when performing a flip or when trying to maintain a specific pose. Athletes are also forced into hyperextension when vaulting and landing, applying excessive stress on the vertebra .

Weightlifting[edit | edit source]

This is another high intensity sport, which involves increased forces. The incidence rate of spondylolysis has been reported to be between 30.7-44%. [21] Studies believe there is a clear relationship between this condition and the stress of lifting. Stone et al.[21] described the actions involved in weightlifting and discussed the excessive impact forces seen during the catching phase of the bar. They also noted that these stress and shear forces are greatly increased through the joints when the athlete completes the jump onto one leg.

Management/Interventions[edit | edit source]

Enabling patients to return to sport is at the forefront of any treatment plan for an athlete following injury. Each athlete must be considered individually in terms of his/her symptoms, functional limitations, their sport and level of participation, as well as any other characteristics which may influence their treatment.[22]

The optimal treatment for athletes with spondylolysis is still widely debated within the literature, with a lack of controlled studies investigating management.[1] However it is generally accepted that the young athlete with spondylolysis should initially be managed conservatively.[23] Surgical management is generally only considered when all conservative methods have failed, with only an estimated 9-15% of all symptomatic cases undergoing surgery.[1]

Conservative Management[edit | edit source]

Conservative treatment is generally the initial management plan for young athletes with spondylolysis[5]. Following conservative management, 92% of individuals are able to return to sport within 6 months.[5] Physiotherapy with these patients aims to restore range of motion, stabilise and strengthen the spine, and to reduce pain. The goal of management should not be focused on radiographic bony healing. Not all lesions heal and bony healing is not associated with quality of life or ability to return to sport.[5]Repeat imaging is therefore not indicated and clinical decision making should rather be based on functional parameters[5].

The most common components of a conservative management plan include:[23][2]

- Rest from activity -cessation of sport activity is recommended for at least 3 months[5]

- Lumbosacral bracing

- Strengthening of: the core, pelvic floor, gluteals, spinal stabilisers and extensors, quadratus lumborum

- Stretching of the hip flexors and hamstrings

Bracing[edit | edit source]

The use and effectiveness of lumbosacral braces is still debated within the literature. The rationale behind bracing is to allow the healing of the bony defect in the pars interarticularis. Further research is necessary to establish its effectiveness - until then it may be recommended in cases that fail to improve with rest alone[5]

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

The optimal time to start with physiotherapy is still debated, but research suggest that starting earlier may lead to earlier return to sport.[5] Physiotherapy should focus on:

- Lumbar stability exercises: exercises targeting the deep abdominals and multifidus has been shown to be superior to general exercise.[5] Watkins describes how strengthening these muscles will provide biomechanically sound spinal function to allow a return to sport[13]

- Sport Specific Exercises: It is important that core stability strengthening is progressed into functional, specific exercises for each athlete following the initial period of retraining/activating the core muscles.[13] For example, in cricket, when focusing on core stability the player is standing on one leg balancing on a soft cushion or trampette while performing the bowling action. This is later progressed by attaching the ball to an elastic band, which is tied to a fixed point behind the player[18].

- Motor control training: Trunk coordination exercises and dynamic lumbar strengthening[5]

Manipulation and Electrotherapy is not recommended as treatment modalities for spondylolysis[5]. Any modalities used for pain relief, it should be sued with the goal of promoting exercise and activity.

Treatment framework proposed by Selhorst et al (2020) [5]:[edit | edit source]

For a more detailed description and criteria for advancing to the next phase, you can read the article here. For more detail on core strengthening see Core Strengthening and the PGM Method

Phase 1 - Isolated[edit | edit source]

Static and neutral lumbar position during exercises - allows muscle activation while avoiding stress on the injured pars interarticularis.

- Patient education to minimise fear of movement and to encourage participation in ADLs

- Target the deep abdominals and multifidus - static spine while performing extremity movements

- Address limitations in flexibility in the upper and lower limb as needed (while maintaining a neutral spine) - especially hip flexors and hamstrings

Phase 2 - integrated[edit | edit source]

As symptoms improve, start to include extension and rotation movements. Although these movements, when performed repetitively and at end-range, place stress on the pars interarticularis, they are still functional movements and are safe when performed in a controlled manner. Progressive restoration of these movements are essential for return to sport.

- Balance and dynamic activities

- Progress endurance of stabilisers - stabilisation during spinal movement and core control in upright positions

Phase 3 - return to sport[edit | edit source]

Address impairments in other regions of the body, as these may increase stress throughout the lumbar spine and should be addressed.

- Sport specific strength and endurance

- Muscle control during sport specific activities

- Graded return to sport

Surgical Interventions[edit | edit source]

The use of surgery for spondylolysis within the young athletic population is seen as a last resort option, after all the methods of conservative treatment fail.[1] There are vast arrays of surgical techniques which can be performed, but most commonly either a screw or wire fixation are the preferred methods.[24]

Surgery has a high success rate in the young athletic population and has been shown to be very effective in returning athletes to their sport.[25] However, in comparison to the conservative approach, surgical treatment did require athletes to have an extended period away from their sport. One study showed an average lay off time of 7 months following surgical treatment.[25] Due the nature of surgery, athletes still require a period of rehabilitation postoperatively.[24] This post operative treatment will include many of the exercises used in the conservative approach, targeting the strengthening of core stability muscles.[24]

Biopsychosocial Factors[edit | edit source]

Sports injuries can have major impacts on an athlete’s career. Some injuries can even terminate their future ability to perform. Psychological issues may impact the rehabilitation of an injured athlete. It is therefore important that an athlete’s rehabilitation programme includes a component that addresses psychological factors. This will in turn aid physical recovery, prevent re-injury, promote return to sport and increase adherence to rehabilitation.[26]

The biopsychosocial model proposed by Brewer et al. [27] shows how psychological and social factors have an impact on injury rehabilitation. The model was designed to widen the focus of rehabilitation. The model shows how characteristics of injury, sociodemographic factors, biological factors, immediate biological outcomes, social factors and psychological factors all affect the sport rehabilitation outcomes.

Injured athletes often experience emotional distress - including decreased self-esteem, anxiety, frustration, isolation and depression.[5] . Therefore, injury can have a great impact on their mental well-being.

Fear can have a huge impact on recovery and return to sport. Many athletes become fearful of re-injury leading to them not training at full intensity. This may also have an impact on adherence to rehabilitation.

Not all athletes suffer from emotional distress post-injury. Self-efficacy, self-esteem, confidence and motivation prior to injury are some factors in particular that can be used to determine an athlete’s reaction post-injury.[28]

These factors need to be taken into consideration when communicating with athletes, and can be addressed through strategies such as emotional support, active listening, reality confirmation and positive support[5]. Counselling can be used to target psychological barriers that may affect an athlete’s return to sport and focus on this specifically. In severe cases of depression, referral to a psychologist may be necessary.

Patient Testimonial[edit | edit source]

Kamal is a 21 year old, cricket player, playing at a competitive University level. He was diagnosed with Spondylolysis 5 years ago. and was treated conservatively with physiotherapy. In his testimony, made by ourselves, Kamal talks about his experiences, treatment, and emotional well being, as a young athlete with spondylolsis.

Role of the MDT[edit | edit source]

The MDT team of an injured athlete would often involve a medical practitioner, coach, physiotherapist and psychologist. Prognosis and realistic time frames need to be well communicated and consistent among team members.

Accurate, non-threatening communication is of vital importance by all team members. Using the wrong language can instil fear in athletes as they perceive their back to be 'broken'. This can increase fear of activity and re-injury[5]. Exaggerated perceptions need to be met with improved language ('bone stress injury' instead of 'broken') and reassurance relating to the good prognosis and positive outcomes seen in athletes.[5]

Case Study[edit | edit source]

This account was taken from a physiotherapist working in an outpatients setting. The case study describes a past patient that she assessed and treated.

A 15 year old keen cricketer and golfer presented with acute right-sided low back pain which had come on suddenly after playing cricket at the weekend; at the time he was unable to run and in fact felt considerable pain walking. During the week before this he had been on a golfing holiday playing a round a day and on some days 2 rounds. He had experienced a dull pain three weeks before and it was always related to cricket. In fact, this young boy recalled some twinges of pain in the previous school term while playing in the nets. He was a fast bowler.

This boy was in good health with no previous episodes of back pain. He had recently had a growth spurt.

On examination there was significant right-sided muscle spasm on lumber movements. There was pain during flexion and right side flexion with an excessive amount of movement available. Right hip flexion was painful and a right straight leg raise resulted in low back pain. On palpation there was pain and resistance at L4/5 and L5/S1.

During the initial treatment manual therapy was used to settle the acute pain and spasm. The patient reported that this eased the pain until he then went and picked up cricket balls from off the floor. He was referred on for further investigations at this point.

An x-ray, including oblique views, showed evidence of a spondylolysthesis of L5/S1. Therefore An MRI was arranged. This clearly showed a bilateral pars interarticularis defect. However there was no forward displacement of L5.

The patient was then instructed to completely rest for the next four months, he was referred back for physiotherapy at this point. Now, on examination, his movements were pain-free. On palpation there was some mild stiffness in the low lumbar spine but the hip and straight leg raise showed no symptoms. Treatment at this point included gentle stability and strengthening exercises.

For example he was encouraged to stretch his hamstrings, use breathing control and begin lower transverse abdominal exercises: spine curls in lying, bridging exercises and stability exercises whilst moving the legs.

These were later progressed onto the Swiss Ball combined with more functional exercises in standing aiming towards cricket related exercises. For example using the overhead movement of the arm taking care not to over extend the lumbar spine. Ensuring there wasn't a hinge point into lumber extension and that rotation was used. It was also worth checking he had enough available shoulder movement.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Syrmou, E., Tsitsopoulos, PP., Marinopoulos, D., Tsonidis, C., Anagnostopoulos, I. and Tsitsopoulos, PD. Spondylolysis: A review and a reappraisal. Hippokratia. 2010;14(1):17-2.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Debnath UK. Lumbar spondylolysis-Current concepts review. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma. 2021 Oct 1;21:101535.

- ↑ Luqmani, R., Robb, J., Porter, D. and Keating, J. Textbook of Orthopaedics, Trauma and Rheumatology. China: Elsevier Limited, 2008.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Krabak, BJ., Carter, CT. Sports Medicine: Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics. North America: Clinical Review Articles Elsevier Health Sciences, 2014.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 5.23 5.24 5.25 Selhorst M, Allen M, McHugh R, MacDonald J. Rehabilitation considerations for spondylolysis in the youth athlete. International journal of sports physical therapy. 2020 Apr;15(2):287.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 McCleary, M. D. and Congeni, J. A. Current concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of spondylolysis in young athletes. Current sports medicine reports. 2007; 6(1): 62-66.

- ↑ Haun D.W. and Kettner, N. W. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: a narrative review of etiology, diagnosis, and conservative management. Journal of chiropractic medicine 2006: 4(4); 206-217.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Lawrence KJ, Elser T, Stromberg R. Lumbar spondylolysis in the adolescent athlete. Physical Therapy in Sport. 2016 Jul 1;20:56-60.

- ↑ Litao, A., Munyak, J., Perron, AD., Talavera, F., Goitz, HT., Whitehurst, JB. and Young, C. Lumbrosacral Spondylolysis Clinical Presentation MedScape. 2013. Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/95691-clinical#showall

- ↑ Alqarni, A., Schneiders, A., Cook, C. and Hendrick, P. Clinical tests to diagnose lumbar spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: A systematic review. Physical Therapy in Sport. 2015; 16(3), pp.268-275.

- ↑ Sundell, CG., Jonsson, H., Adin, L. and Larsen, KH. Clinical Examination, Spondylolysis and Adolescent Athletes International Journal of Sports Medicine. 2013; 34(3): 263-267

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Masci, L., Pike, J., Malara, F., Phillips, B., Bennell, K. & Brukner, P. Use of one-legged hyperextension test and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of active spondylolysis British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2006; 40(11): 940-946.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Watkins IV, RG. & Watkins III, RG. Lumbar Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis in Athletes Seminars in Spine Surgery. 2010; 22(4): 210-217

- ↑ McCleary, M. D. and Congeni, J. A. Current concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of spondylolysis in young athletes. Current sports medicine reports. 2007; 6(1): 62-66.

- ↑ Therriault T, Rospert A, Selhorst M, Fischer A. Development of a preliminary multivariable diagnostic prediction model for identifying active spondylolysis in young athletes with low back pain. Physical Therapy in Sport. 2020 Sep 1;45:1-6.

- ↑ Tofte JN, CarlLee TL, Holte AJ, Sitton SE, Weinstein SL. Imaging pediatric spondylolysis: a systematic review. Spine. 2017 May 15;42(10):777-82.

- ↑ Gregory, P. L., Batt, M. E., & Wallace, W. A. Comparing injuries of spin bowling with fast bowling in young cricketers. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine.2002; 12(2):107-112.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Becker, C. Lumbar Spondylolysis: Diagnosis and Rehabilitation. Sport Ex Journal. 2006;30:6-9.

- ↑ Guillodo, Y., Botton, E., Saraux, A., & Le Goff, P. Contralateral spondylolysis and fracture of the lumbar pedicle in an elite female gymnast: a case report. Spine. 2000;25(19): 2541-2543.

- ↑ Kruse, D. and Lemmen, B. Spine injuries in the sport of gymnastics. Current sports medicine reports. 2009;8(1): 20-28.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Stone, M. H., Fry, A. C., Ritchie, M., Stoessel-Ross, L., & Marsit, J. L. Injury potential and safety aspects of weightlifting movements. Strength and Conditioning Journal. 1994; 16(3): 15-21.

- ↑ Standaert, CJ & Herring SA. Expert Opinion and Controversies in Sports and Musculoskeletal Medicine: A Diagnosis and Treatment of Spondylolysis in Adolescent Athletes Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2007; 88(4): 537-540.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 McNeely, M. L., Torrance, G. and Magee, D. J. A systematic review of physiotherapy for spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Manual therapy. 2003; 8(2), 80-91.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Drazin D., Shirzadi A., Jeswani S., Ching H., Rosner J., Rasouli A. et al. Direct surgical repair of spondylolysis in athletes: indications, techniques, and outcomes. Neurosurgical focus. 2011: 31(5); E9.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Debnath, U. K., Freeman, B. J. C., Gregory, P., de la Harpe, D., Kerslake, R. W. and Webb, J. K. Clinical outcome and return to sport after the surgical treatment of spondylolysis in young athletes. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, British. 2003;Volume, 85(2), 244-249.

- ↑ Schwab Reese, LM., Pittsinger, R. and Wang, J. Effectiveness of psychological intervention following sport injury Journal of Sport and Health Science. 2012; 1(2): 71-79.

- ↑ Brewer, BW., Anderson, MB. & Van Raalte, JI. Psychological Aspects of Sport Injury Rehabilitation: Toward a Biopsychosocial Approach Medical and Psychological Aspects of Sport and Exercise 41-54 D. Morgantown: WV Fitness Information Technology. 2002.

- ↑ Wagman, D. and Khelifa, M. Psychological Issues in Sport Injury Rehabilitation: Current Knowledge and Practice Journal of Athletic Training. 1996; 31(3): 257-26.