Recognising Pelvic Girdle Pain: Difference between revisions

(risk factors, added links) |

No edit summary |

||

| (38 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> '''Original Editor '''- [https://members.physio-pedia.com/course_tutor/deborah-riczo/ Deborah Riczo], [[User:Wanda van Niekerk|Wanda van Niekerk]]<br> | |||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}}</div> | |||

<div class="editorbox"> | |||

'''Original Editor '''- [[User: | |||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

[[File:Sacroiliac joint.png|right|frameless]] | |||

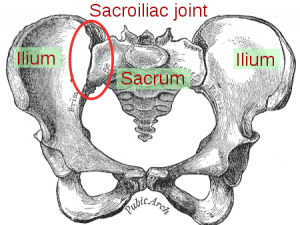

Pelvic girdle pain (PGP) refers to musculoskeletal disorders affecting the [[pelvis]]. | |||

* It primarily involves the [[Sacroiliac Joint|sacroiliac joint]], the [[Pubic Symphysis Dysfunction|symphysis pubis]] and the associated [[ligament]]<nowiki/>s and [[muscle]]<nowiki/>s. | |||

* It is a common condition during pregnancy and postpartum, more common in women in general than in men. | |||

* It is a disabling condition and has an impact on daily function and [[Quality of Life|quality of life]],<ref>Ceprnja D, Chipchase L, Liamputtong P, Gupta A. [https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-022-04426-3 "This is hard to cope with": the lived experience and coping strategies adopted amongst Australian women with pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy]. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022 Feb 2;22(1):96. </ref> contributes to [[depression]], [[Generalized Anxiety Disorder|anxiety]], work absenteeism, and disability. | |||

The vast majority of studies on pelvic girdle pain look at women during pregnancy and postpartum due to the prevalence of PGP in this population. | |||

People struggling with PGP are commonly managed by physiotherapists.<ref>Beales D, Hope JB, Hoff TS, Sandvik H, Wergeland O, Fary R. Current practice in management of pelvic girdle pain amongst physiotherapists in Norway and Australia. Manual therapy. 2015 Feb 1;20(1):109-16.</ref><ref name=":12" /><ref>Vøllestad NK, Stuge B. Prognostic factors for recovery from postpartum pelvic girdle pain. ''Eur Spine J''. 2009;18(5):718-726. doi:10.1007/s00586-009-0911-2</ref>{{#ev:youtube|watch?v=AmDxtQtJV_0}}<ref>Oslo universitetssykehus. Pelvic Girdle Pain - Explained by FORMI. Published on 21 June 2019. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AmDxtQtJV_0. (last accessed 12 August 2020)</ref> | |||

== Definition of Pelvic Girdle Pain == | == Definition of Pelvic Girdle Pain == | ||

There are various definitions of Pelvic Girdle Pain and historically there have been discrepancies around the terminology regarding pelvic pain and/or low back pain, specifically in the pregnant population.<ref>Bergström C, Persson M, Mogren I. Pregnancy-related low back pain and pelvic girdle pain approximately 14 months after pregnancy–pain status, self-rated health and family situation. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2014 Dec 1;14(1):48.</ref> The European guidelines | There are various definitions of Pelvic Girdle Pain and historically there have been discrepancies around the terminology regarding pelvic pain and/or [[Low Back Pain|low back pain]], specifically in the pregnant population.<ref>Bergström C, Persson M, Mogren I. Pregnancy-related low back pain and pelvic girdle pain approximately 14 months after pregnancy–pain status, self-rated health and family situation. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2014 Dec 1;14(1):48.</ref> The European guidelines define pelvic girdle pain as: | ||

"Pelvic pain that arises in relation to pregnancy, trauma, arthritis and osteoarthritis. Pain is experienced between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal folds, particularly in the vicinity of the sacroiliac joint. The pain may radiate in the posterior thigh and can also occur in conjunction with/or separately in the symphysis."<ref>Vleeming A, Albert HB, Östgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. European Spine Journal. 2008 Jun 1;17(6):794-819.</ref> | '''"Pelvic pain that arises in relation to pregnancy, trauma, arthritis and osteoarthritis. Pain is experienced between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal folds, particularly in the vicinity of the sacroiliac joint. The pain may radiate in the posterior thigh and can also occur in conjunction with/or separately in the symphysis."'''<ref name=":8">Vleeming A, Albert HB, Östgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. European Spine Journal. 2008 Jun 1;17(6):794-819.</ref> | ||

Clinton et al | Clinton et al.<ref name=":0">Clinton SC, Newell A, Downey PA, Ferreira K. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Susan_Clinton/publication/318165310_Clinical_Practice_Guidelines/links/59ef810da6fdcce2096dbe06/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines.pdf Pelvic girdle pain in the antepartum population: physical therapy clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health from the section on women's health and the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association]. Journal of Women's Health Physical Therapy. 2017 May 1;41(2):102-25.</ref> agrees with the above definition in their clinical practice guidelines for pelvic girdle pain in the antepartum population. | ||

Another term that is also used is pregnancy-related low back pain (PLBP) and should not be confused with pelvic girdle pain (PGP). Pregnancy-related low back pain is characterised by a dull pain, more pronounced in forward flexion, with associated restriction in lumbar spine movement.<ref name=":5">Vermani E, Mittal R, Weeks A. Pelvic girdle pain and low back pain in pregnancy: a review. Pain Practice. 2010 Jan;10(1):60-71.</ref> Palpation of the erector spinae muscles exacerbates pain.<ref name=":5" /> | Another term that is also used is [[Low Back Pain and Pregnancy|pregnancy-related low back pain (PLBP)]] and should not be confused with pelvic girdle pain (PGP). | ||

* Pregnancy-related low back pain is characterised by a dull pain, more pronounced in forward flexion, with associated restriction in lumbar spine movement.<ref name=":5">Vermani E, Mittal R, Weeks A. Pelvic girdle pain and low back pain in pregnancy: a review. Pain Practice. 2010 Jan;10(1):60-71.</ref> Palpation of the [[Erector Spinae|erector spinae]] muscles exacerbates pain.<ref name=":5" /> | |||

Women who have both PLBP and PGP are more likely to continue to have problems after pregnancy.<ref name=":12" /> | |||

The above definition of pelvic girdle pain is most often used in the physiotherapist literature, but others use “pelvic girdle pain” to include areas of pain in the pelvis from visceral origin<ref name=":13">Palmer E, Redavid L. Pelvic Girdle Pain: an Overview. Richman S, ed. ''CINAHL Rehabilitation Guide''. Published online August 2, 2019</ref>. | |||

Other causes of pelvic pain | == Other Causes of Pelvic Girdle Pain == | ||

In 2019, Palmer et al.<ref name=":13" /> described other causes of pelvic pain:<ref name=":13" /> | |||

* [[Endometriosis]] | * [[Endometriosis]] | ||

* Dysmenorrhea | * Dysmenorrhea | ||

* Vulvodynia | * Vulvodynia | ||

* [[Crohn's Disease|Crohn’s disease]] | * [[Crohn's Disease|Crohn’s disease]] | ||

* [[Irritable Bowel Syndrome|Irritable | * [[Irritable Bowel Syndrome|Irritable bowel syndrome]] (IBS) | ||

* Ulcerative colitis | * Ulcerative colitis | ||

* [[Septic (Infectious) Arthritis|Septic arthritis]] | * [[Septic (Infectious) Arthritis|Septic arthritis]] | ||

* [[Osteomyelitis]] | * [[Osteomyelitis]] | ||

* Sexually | * Sexually transmitted diseases/infections (STDs or STIs) | ||

* [[Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm|Abdominal aneurysms]] | * [[Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm|Abdominal aneurysms]] | ||

* [[ | * [[Oncology|Cancer]] | ||

Physiotherapists | Physiotherapists who specialise in pelvic health are trained to recognise these other causes of pelvic pain.<ref name=":6">Deborah Riczo. Recognising Pelvic Girdle Pain. Course. Plus. 2020</ref> For the purpose of this page, "pelvic girdle pain" (PGP) will be used to refer to the musculoskeletal causes of pelvic girdle pain | ||

== Causes of Pelvic Girdle Pain == | |||

[[File:Pregnant.jpeg|right|frameless]] | |||

Causes of pelvic girdle pain may include the following: | |||

* Changes in [[hormones]], tissue laxity, weight distribution/gain, muscle weakness/tightness associated with pregnancy and postpartum | |||

* Trauma<ref name=":6" /> | |||

* A [[Falls|fall]] | |||

* A motor vehicle accident | |||

* Falling downstairs | |||

* Stepping into a hole | |||

* Sports injuries | |||

* [[Arthritis]] or [[osteoarthritis]] | |||

== Differential Diagnosis == | == Differential Diagnosis == | ||

In the | In the antepartum population, pelvic girdle pain can be associated with signs and symptoms of various inflammatory, infective, traumatic, neoplastic, degenerative or [[Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders|metabolic disorders]].<ref name=":0" /> The physiotherapist should proceed with caution or consider medical referral if there is a history of any of the following:<ref name=":0" /><ref>Koes BW, Van Tulder M, Lin CW, Macedo LG, McAuley J, Maher C. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. European Spine Journal. 2010 Dec 1;19(12):2075-94.</ref> | ||

* History of trauma | * History of trauma | ||

* Unexplained weight loss | * Unexplained weight loss | ||

* History of cancer | * History of cancer | ||

* Steroid use | * [[Corticosteroid Medication|Steroid]] use | ||

* Drug abuse | * Drug abuse | ||

* Human immunodeficiency virus or immunosuppressed state | * [[Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)|Human immunodeficiency virus]] or [[Immunocompromised Client|immunosuppressed]] state | ||

* Neurological symptoms/signs | * Neurological symptoms/signs | ||

* Fever and/or feeling systemically unwell | * [[Fever]] and/or feeling systemically unwell | ||

* Special considerations for Pelvic Girdle Pain should include: | * Special considerations for Pelvic Girdle Pain should include: | ||

** Symptoms due to uterine abruption | ** Symptoms due to uterine abruption | ||

** Referred pain due to urinary tract infection to the lower abdomen/pelvic or sacral region | ** Referred pain due to [[Urinary Tract Infection|urinary tract infection]] to the lower abdomen/pelvic or sacral region | ||

* Other factors that may require medical specialist referral include: | * Other factors that may require medical specialist referral include: | ||

** No functional improvement | ** No functional improvement | ||

** Pain not reducing with rest | ** [[Pain Behaviours|Pain not reducing with rest]] | ||

** Severe, disabling pain | ** [[Pain Assessment|Severe, disabling pain]] | ||

Other differential diagnoses may include: | Other differential diagnoses for pelvic girdle pain, after the above pelvic pain disorders have been ruled out may include: | ||

* [[Diastasis recti abdominis|Diastasis Rectus Abdominis (DRA)]] | * [[Diastasis recti abdominis|Diastasis Rectus Abdominis (DRA)]] | ||

** Pelvic floor weakness associated with weakness of abdominal wall in DRA<ref>Gutke A, Östgaard HC, Öberg B. Predicting persistent pregnancy-related low back pain. Spine. 2008 May 20;33(12):E386-93.</ref> | ** Pelvic floor weakness associated with weakness of abdominal wall in DRA<ref>Gutke A, Östgaard HC, Öberg B. Predicting persistent pregnancy-related low back pain. Spine. 2008 May 20;33(12):E386-93.</ref> | ||

** 66% incidence of DRA in antepartum population in third trimester | ** 66% incidence of DRA in antepartum population in the third trimester | ||

** DRA occurs in 39% of the postpartum population after 7 weeks to several years<ref name=":0" /> | ** DRA occurs in 39% of the postpartum population after 7 weeks to several years<ref name=":0" /> | ||

* Other orthopaedic problems | * Other orthopaedic problems | ||

| Line 76: | Line 83: | ||

** Muscle strains<ref name=":7" /> | ** Muscle strains<ref name=":7" /> | ||

** Referred pain from L2/3 [[radiculopathy]] | ** Referred pain from L2/3 [[radiculopathy]] | ||

** | ** Osteonecrosis of the femoral head<ref name=":7" /> | ||

** [[Paget's Disease|Paget’s disease]]<ref name=":7" /> | ** [[Paget's Disease|Paget’s disease]]<ref name=":7" /> | ||

** [[Arthritis]] – [[Rheumatoid Arthritis|rheumatoid]], [[Psoriatic Arthritis|psoriatic]] and [[Septic (Infectious) Arthritis|septic]]<ref name=":7" /> | ** [[Arthritis]] – [[Rheumatoid Arthritis|rheumatoid]], [[Psoriatic Arthritis|psoriatic]] and [[Septic (Infectious) Arthritis|septic]]<ref name=":7" /> | ||

| Line 82: | Line 89: | ||

** [[Spondylolisthesis]] | ** [[Spondylolisthesis]] | ||

** [[Lumbar Discogenic Pain|Disc injury]] patterns with symptoms that fail to centralise | ** [[Lumbar Discogenic Pain|Disc injury]] patterns with symptoms that fail to centralise | ||

** Neurological screening that | ** Neurological screening that indicates the presence of lower motor neuron or upper motor neuron signs | ||

** Bowel/bladder dysfunction should be considered in combination with multiple sensory, motor and diminished reflexes as this could indicate [[Cauda Equina Syndrome|cauda equina syndrome]], large lumbar disc, etc. | ** Bowel/bladder dysfunction should be considered in combination with multiple sensory, motor and diminished reflexes as this could indicate [[Cauda Equina Syndrome|cauda equina syndrome]], large lumbar disc, etc. | ||

== Prevalence of Pelvic Girdle Pain == | == Prevalence of Sacroiliac Pain, a Type of Pelvic Girdle Pain == | ||

Between 5 – 10% of people develop chronic low back pain worldwide. This leads to<ref>Meucci RD, Fassa AG, Faria NM. Prevalence of chronic low back pain: systematic review. Revista de saude publica. 2015 Oct 20;49:73.</ref>: | |||

* High treatment costs | * High treatment costs | ||

* Extended periods of sick leave | * Extended periods of sick leave | ||

* Individual suffering | * Individual suffering | ||

* Invasive interventions such as surgeries | * Invasive interventions such as [[Surgery and General Anaesthetic|surgeries]] | ||

* Disability | * Disability | ||

Sacroiliac pain, a type of pelvic girdle pain, has been known to be undiagnosed or mistreated in people with low back pain. It is estimated to occur in 10-30% of persons with non-specific low back pain<ref>Booth J, Morris S. The sacroiliac joint–Victim or culprit. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2019 Feb 1;33(1):88-101.</ref>. Some studies have found this incidence even higher. | |||

In a 2013 study by Visser et al.,<ref name=":2">Visser LH, Nijssen PG, Tijssen CC, Van Middendorp JJ, Schieving J. Sciatica-like symptoms and the sacroiliac joint: clinical features and differential diagnosis. European Spine Journal. 2013 Jul 1;22(7):1657-64.</ref> 40 percent of the study population had a sacroiliac joint or sacroiliac joint and [[Intervertebral disc|disc]] component. Visser et al.<ref name=":2" /> noted that lumbar nerve root compression can mimic sacroiliac joint [[radiculopathy]] and thorough evaluations of the spine, hips and sacroiliac joint should be done to get an accurate diagnosis. | |||

[[File:Pregnant walker.jpeg|right|frameless]] | |||

=== Prevalence of Pregnancy-Related Lumbar Back Pain (PLBP) and Pelvic Girdle Pain === | === Prevalence of Pregnancy-Related Lumbar Back Pain (PLBP) and Pelvic Girdle Pain === | ||

* 56% to 72% of the antepartum population<ref name=":3">Wu WH, Meijer OG, Uegaki K, Mens JM, Van Dieen JH, Wuisman PI, Östgaard HC. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (PPP), I: Terminology, clinical presentation, and prevalence. European Spine Journal. 2004 Nov 1;13(7):575-89.</ref><ref name=":4">Mens JM, Huis YH, Pool-Goudzwaard A. Severity of signs and symptoms in lumbopelvic pain during pregnancy. Manual therapy. 2012 Apr 1;17(2):175-9.</ref> | * 56% to 72% of the antepartum population<ref name=":3">Wu WH, Meijer OG, Uegaki K, Mens JM, Van Dieen JH, Wuisman PI, Östgaard HC. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (PPP), I: Terminology, clinical presentation, and prevalence. European Spine Journal. 2004 Nov 1;13(7):575-89.</ref><ref name=":4">Mens JM, Huis YH, Pool-Goudzwaard A. Severity of signs and symptoms in lumbopelvic pain during pregnancy. Manual therapy. 2012 Apr 1;17(2):175-9.</ref> | ||

* 20% of antepartum population report severe symptoms during 20 -30 weeks of gestation<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":4" /> | * 20% of antepartum population report severe symptoms during 20 -30 weeks of gestation<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":4" /> | ||

* 7% of women with pelvic girdle pain will | * 7% of women with pelvic girdle pain will experience lifelong problems<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":4" /> | ||

* 33% | * 33% to 50% of pregnant females report PGP before 20 weeks of gestation and prevalence may reach 60 to 70% in late pregnancy<ref>Robinson HS, Mengshoel AM, Veierød MB, Vøllestad N. Pelvic girdle pain: potential risk factors in pregnancy in relation to disability and pain intensity three months postpartum. Manual therapy. 2010 Dec 1;15(6):522-8.</ref> | ||

Considering this high prevalence, it is evident that pelvic girdle pain remains a significant problem globally. | Considering this high prevalence, it is evident that pelvic girdle pain remains a significant problem globally. There is, however, no gold standard testing protocol<ref>Riczo D. Recognising Pelvic Girdle Pain Course. Plus, 2021.</ref>; currently various combinations of provocation tests and imaging are used in research to diagnose pelvic girdle pain.<ref>Thawrani DP, Agabegi SS, Asghar F. Diagnosing Sacroiliac Joint Pain. ''JAAOS - Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons''. 2019;Publish Ahead of Print.</ref> Physiotherapists are best placed to offer and provide individuals with guidance and help in this area.<ref name=":6" /> Further research is needed to guide physiotherapy interventions.<ref name=":6" /> | ||

== Risk | == Risk Factors for Pelvic Girdle Pain == | ||

Clinton et al. (2017) list the following risk factors based upon strong evidence<ref name=":0" />: | |||

* Prior history of pregnancy | * Prior history of pregnancy | ||

* Orthopaedic dysfunctions | * Orthopaedic dysfunctions | ||

* Joint hypermobility | * [[Obesity|Increased body mass index]] (BMI)<ref>Stendal Robinson H, Lindgren A, Bjelland EK. [https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09593985.2021.1913774 Generalized joint hypermobility and risk of pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy: does body mass index matter?] Physiother Theory Pract. 2022 Dec;38(12):2222-9. </ref> | ||

* History of multiparity | * [[Smoking Cessation and Brief Intervention|Smoking]] | ||

* Hip and/or lower extremity dysfunction including the presence of gluteus medius and pelvic floor muscle dysfunction | * Work dissatisfaction | ||

* Lack of belief in improvement in the prognosis of pelvic girdle pain | |||

They also list these risk factors that might lead to the development of pelvic girdle pain<ref name=":0" />: | |||

* Joint [[Hypermobility Syndrome|hypermobility]] | |||

* History of multiparity (i.e have had more than one child) | |||

* Periods of amenorrhea | |||

* Hip and/or lower extremity dysfunction including the presence of [[Gluteus Medius|gluteus medius]] and [[Pelvic Floor and Other Pelvic Disorders|pelvic floor muscle]] dysfunction | |||

* History of trauma to the pelvis | * History of trauma to the pelvis | ||

* History of low back pain and/or PGP, especially in previous pregnancies | * History of low back pain and/or PGP, especially in previous pregnancies | ||

In pregnancy, Ceprnja et al.<ref>Ceprnja D, Chipchase L, Fahey P, Liamputtong P, Gupta A. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8221721/ Prevalence and factors associated with pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy in Australian women: a cross-sectional study]. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2021 Jul 15;46(14):944-9. </ref> note that a history of low back pain and/or pelvic girdle pain and a family history of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain. is associated with pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain was consistent with previous studies. | |||

=== Risk | === Risk Factors for Persistent Pelvic Girdle Pain Postpartum === | ||

In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis the following risk factors for persistent pelvic girdle pain postpartum have been identified<ref>Wiezer M, Hage-Fransen MA, Otto A, Wieffer-Platvoet MS, Slotman MH, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW, Pool-Goudzwaard AL. Risk factors for pelvic girdle pain postpartum and pregnancy related low back pain postpartum; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice. 2020 May 5:102154.</ref>: | In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis the following risk factors for persistent pelvic girdle pain postpartum have been identified<ref>Wiezer M, Hage-Fransen MA, Otto A, Wieffer-Platvoet MS, Slotman MH, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW, Pool-Goudzwaard AL. Risk factors for pelvic girdle pain postpartum and pregnancy related low back pain postpartum; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice. 2020 May 5:102154.</ref>: | ||

* History of low back pain | * History of low back pain | ||

| Line 129: | Line 136: | ||

== Clinical Presentation of Pelvic Girdle Pain == | == Clinical Presentation of Pelvic Girdle Pain == | ||

The clinical presentation varies from patient to patient and can also change over the course of a pregnancy. | |||

* | |||

* Pain resolves by 3rd month postpartum | === Subjective History === | ||

* Pain experienced between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal fold, particularly in the vicinity of the sacroiliac joints (SIJ) and/or the pubic symphysis | |||

==== Symptoms indicative of PGP as described by Clinton et al (2017) based on the European Guidelines:<ref name=":0" /> ==== | |||

* Pain experienced between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal fold, particularly in the area of the sacroiliac joint (SIJ) | |||

* The pain may radiate in the posterior thigh | |||

* Pain can occur in conjunction with/or separately from pain in the pubic symphysis | |||

==== Pain ==== | |||

* The onset of pain may occur around the 18th week of pregnancy and may reach peak intensity between the 24th and 36th week of pregnancy<ref name=":9">Kanakaris NK, Roberts CS, Giannoudis PV. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: an update. BMC medicine. 2011 Dec 1;9(1):15.</ref> | |||

* Pain resolves by the 3rd month postpartum<ref name=":9" /> | |||

* Pain experienced between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal fold, particularly in the vicinity of the sacroiliac joints (SIJ) and/or the pubic symphysis<ref name=":8" /> | |||

* Pain can be local or local with radiculopathy | * Pain can be local or local with radiculopathy | ||

* Fortin’s area – rectangular area that runs from the PSIS | * Fortin’s area – a rectangular area that runs from the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) 3 cm lateral and 10 cm caudal<ref name=":10">Fortin JD, Falco FJ. The Fortin finger test: an indicator of sacroiliac pain. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF ORTHOPEDICS-BELLE MEAD-. 1997 Jul;26:477-80.</ref> | ||

* One finger method - | * One finger method - the person will often use one finger to point to the painful area, usually within this rectangular area<ref name=":10" /> | ||

* Radicular component of sacroiliac pain | * Radicular component of sacroiliac pain – initially it was thought that radicular pain past the knee is not related to SIJ dysfunction but Fortin et al.<ref>Fortin JD, Vilensky JA, Merkel GJ. Can the sacroiliac joint cause sciatica?. Pain physician. 2003 Jul;6(3):269-72.</ref> showed that radicular pain from the SIJ can go past the knee and that it can be a cause of SIJ dysfunction. Visser et al.<ref name=":2" /> also reported a combination of SIJ and disc-related radicular pain | ||

* Pain may be described as stabbing, dull, shooting or burning sensation<ref>Sturesson B, Uden G, Uden A. Pain Pattern in Pregnancy and" Catching" of the Leg in Pregnant Women With Posterior Pelvic Pain. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 1998 Mar 1;53(3):136-7.</ref> | |||

* Pain may be described as stabbing, dull, shooting or burning sensation | * Pain intensity on [[Visual Analogue Scale]] averages around 50 -60mm<ref>Kristiansson P, Svärdsudd K, von Schoultz B. Back pain during pregnancy: a prospective study. Spine. 1996 Mar 15;21(6):702-8.</ref> | ||

* Pain intensity on | * Differentiation between PGP and PLBP – useful to use a patient pain distribution diagram<ref name=":0" /> | ||

* Differentiation between PGP and PLBP – useful to use a patient pain distribution diagram | ** PGP – located under the PSIS in the gluteal area, the posterior thigh and the groin (specifically over the pubic symphysis) | ||

** PLBP – concentrated in the lumbar region, above the [[sacrum]] | |||

=== Functional Complaints === | ==== Functional Complaints ==== | ||

Issues with transitional movements such as: | Issues with transitional movements such as<ref name=":3" /><ref>Nielsen LL. Clinical findings, pain descriptions and physical complaints reported by women with post‐natal pregnancy‐related pelvic girdle pain. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2010 Sep;89(9):1187-91</ref>: | ||

* Difficulty getting out of a car | * Difficulty getting out of a car | ||

* Difficulty getting up or out of chair | * Difficulty getting up or out of the chair | ||

* Difficulty with mobility | * Difficulty with mobility | ||

* May have difficulty with stairs | * May have difficulty with stairs | ||

* May have difficulty with walking | * May have difficulty with walking | ||

* Difficulty with standing on one leg – | * Difficulty standing for 30 minutes or longer | ||

* | * Difficulty with standing on one leg – failed load transfer – going from one leg to another | ||

* Difficulty turning over in bed - often the worst symptom | |||

* Decreased ability to do housework | |||

* Pain/discomfort with weight-bearing activities | |||

{{#ev:youtube|watch?v=TpofUYC3ePs}}<ref>PregActive. Pelvic Girdle Pain – Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment. Published on 5 August 2018. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TpofUYC3ePs. (last accessed 12 August 2020)</ref> | |||

== Prognosis == | |||

Bergström et al.<ref name=":11">Bergström C, Persson M, Mogren I. Pregnancy-related low back pain and pelvic girdle pain approximately 14 months after pregnancy–pain status, self-rated health and family situation. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2014 Dec 1;14(1):48.</ref> investigated pregnancy-related low back pain and pelvic girdle pain 14 months after pregnancy. A cohort of 639 women with pregnancy-related back pain or pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy were included in the study. The participants completed questionnaires on pain status and self-rated health and family situations. Follow-up was done 6 months after the initial assessment and of the 639 participants, 200 participants reported having postpartum low back pain or pelvic girdle pain. Another follow-up was completed 14 months after and of the 200 that reported pain after 6 months, 176 completed the questionnaires. Of these participants, 19.3% were in remission and 75.3% reported experiencing recurrent low back pain. At 40 months after the initial assessment, 15.3% of participants reported continuous low back and pelvic girdle pain.<ref name=":11" /> | |||

== | In a long-term follow-up study, Bergstrom et al.<ref name=":12">Bergström C, Persson M, Nergård KA, Mogren I. Prevalence and predictors of persistent pelvic girdle pain 12 years postpartum. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2017 Dec 1;18(1):399.</ref> reported that 40.3% of the study participants reported pain to various degrees. The following factors were identified as being associated with a statistically significant increase in the odds of reporting pain 12 years postpartum:<ref name=":12" /> | ||

Wuytak et al | * Increased duration of pain and/or persistency of pain | ||

* How participants self-rated their health | |||

* The prevalence of [[sciatica]], neck and/or [[Thoracic Back Pain|thoracic spinal pain]] | |||

* Sick leave within the past 12 months | |||

* Treatment sought | |||

* Use of prescription and/or non-prescription medication | |||

Bergstrom et al.<ref name=":12" /> concluded that for a subgroup of women with pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain, spontaneous recovery with no recurrences is unlikely. The strongest predictors of poor long-term outcome were:<ref name=":12" /> | |||

* Persistency and/or duration of pain syndromes | |||

* Widespread pain - this may also contribute to long-term sick leave and disability pension | |||

The development of a screening tool to identify women at risk of developing pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain is needed in order to enable early intervention.<ref name=":12" /> | |||

Wuytak et al.<ref name=":1">Wuytack F, Daly D, Curtis E, Begley C. Prognostic factors for pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain, a systematic review. Midwifery. 2018 Nov 1;66:70-8.</ref> conducted a systematic review and identified potential prognostic factors for up to one year postpartum. Only three studies were included in the final review and the quality of evidence for all the factors was rated as low or very low. This could be attributed to the lack of replication, with none of the factors being investigated in more than one study. Considering the uncertainty about the results and the inherent susceptibility to bias the following prognostic factors have been identified in women who are less likely to recover 12 weeks postpartum:<ref name=":1" /> | |||

* History of low back pain | * History of low back pain | ||

* Pain in three to four pelvic locations | * Pain in three to four pelvic locations | ||

* Overweight | * Overweight | ||

* Six months postpartum, pelvic girdle pain | * Six months postpartum, pelvic girdle pain is more likely to persist in: | ||

** | ** Use of [[crutches]] during pregnancy by an individual | ||

** | ** Severe pain in all three pelvic locations during pregnancy | ||

** Presence of other pain conditions | ** Presence of other pain conditions | ||

** Obesity | ** Obesity | ||

** Younger age of menarche | ** Younger age of menarche | ||

** History of previous low back pain | ** History of previous low back pain | ||

** High co-morbidity index | ** High [[Multimorbidity|co-morbidity]] index | ||

** Smoking – conflicting evidence | ** Smoking – conflicting evidence | ||

** Mode of birth in subgroup of women who had to use crutches during pregnancy, with women who had instrumental birth or | ** Mode of birth in the subgroup of women who had to use crutches during pregnancy, with women who had instrumental birth or [[Cesarean Section|cesarean]] section more likely to have persistent (severe) PGP | ||

** Emotional distress during pregnancy | ** Emotional distress during pregnancy | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Course Pages]] | |||

[[Category:Plus Content]] | |||

[[Category:Pelvic Health]] | |||

[[Category:Womens Health]] | |||

Revision as of 22:45, 26 December 2022

Top Contributors - Wanda van Niekerk, Kim Jackson, Tarina van der Stockt, Lucinda hampton and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Pelvic girdle pain (PGP) refers to musculoskeletal disorders affecting the pelvis.

- It primarily involves the sacroiliac joint, the symphysis pubis and the associated ligaments and muscles.

- It is a common condition during pregnancy and postpartum, more common in women in general than in men.

- It is a disabling condition and has an impact on daily function and quality of life,[1] contributes to depression, anxiety, work absenteeism, and disability.

The vast majority of studies on pelvic girdle pain look at women during pregnancy and postpartum due to the prevalence of PGP in this population.

People struggling with PGP are commonly managed by physiotherapists.[2][3][4]

Definition of Pelvic Girdle Pain[edit | edit source]

There are various definitions of Pelvic Girdle Pain and historically there have been discrepancies around the terminology regarding pelvic pain and/or low back pain, specifically in the pregnant population.[6] The European guidelines define pelvic girdle pain as:

"Pelvic pain that arises in relation to pregnancy, trauma, arthritis and osteoarthritis. Pain is experienced between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal folds, particularly in the vicinity of the sacroiliac joint. The pain may radiate in the posterior thigh and can also occur in conjunction with/or separately in the symphysis."[7]

Clinton et al.[8] agrees with the above definition in their clinical practice guidelines for pelvic girdle pain in the antepartum population.

Another term that is also used is pregnancy-related low back pain (PLBP) and should not be confused with pelvic girdle pain (PGP).

- Pregnancy-related low back pain is characterised by a dull pain, more pronounced in forward flexion, with associated restriction in lumbar spine movement.[9] Palpation of the erector spinae muscles exacerbates pain.[9]

Women who have both PLBP and PGP are more likely to continue to have problems after pregnancy.[3]

The above definition of pelvic girdle pain is most often used in the physiotherapist literature, but others use “pelvic girdle pain” to include areas of pain in the pelvis from visceral origin[10].

Other Causes of Pelvic Girdle Pain[edit | edit source]

In 2019, Palmer et al.[10] described other causes of pelvic pain:[10]

- Endometriosis

- Dysmenorrhea

- Vulvodynia

- Crohn’s disease

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

- Ulcerative colitis

- Septic arthritis

- Osteomyelitis

- Sexually transmitted diseases/infections (STDs or STIs)

- Abdominal aneurysms

- Cancer

Physiotherapists who specialise in pelvic health are trained to recognise these other causes of pelvic pain.[11] For the purpose of this page, "pelvic girdle pain" (PGP) will be used to refer to the musculoskeletal causes of pelvic girdle pain

Causes of Pelvic Girdle Pain[edit | edit source]

Causes of pelvic girdle pain may include the following:

- Changes in hormones, tissue laxity, weight distribution/gain, muscle weakness/tightness associated with pregnancy and postpartum

- Trauma[11]

- A fall

- A motor vehicle accident

- Falling downstairs

- Stepping into a hole

- Sports injuries

- Arthritis or osteoarthritis

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

In the antepartum population, pelvic girdle pain can be associated with signs and symptoms of various inflammatory, infective, traumatic, neoplastic, degenerative or metabolic disorders.[8] The physiotherapist should proceed with caution or consider medical referral if there is a history of any of the following:[8][12]

- History of trauma

- Unexplained weight loss

- History of cancer

- Steroid use

- Drug abuse

- Human immunodeficiency virus or immunosuppressed state

- Neurological symptoms/signs

- Fever and/or feeling systemically unwell

- Special considerations for Pelvic Girdle Pain should include:

- Symptoms due to uterine abruption

- Referred pain due to urinary tract infection to the lower abdomen/pelvic or sacral region

- Other factors that may require medical specialist referral include:

- No functional improvement

- Pain not reducing with rest

- Severe, disabling pain

Other differential diagnoses for pelvic girdle pain, after the above pelvic pain disorders have been ruled out may include:

- Diastasis Rectus Abdominis (DRA)

- Other orthopaedic problems

- Presence of hip dysfunction

- Possibility of femoral neck stress fracture due to transient osteoporosis[14]

- Hip bursitis/ tendinopathy[15]

- Chondral damage/loose bodies[15]

- Capsular laxity[15]

- Femoroacetabular impingement[15]

- Labral irritations/tears[15]

- Muscle strains[15]

- Referred pain from L2/3 radiculopathy

- Osteonecrosis of the femoral head[15]

- Paget’s disease[15]

- Arthritis – rheumatoid, psoriatic and septic[15]

- Lumbar spine dysfunctions

- Spondylolisthesis

- Disc injury patterns with symptoms that fail to centralise

- Neurological screening that indicates the presence of lower motor neuron or upper motor neuron signs

- Bowel/bladder dysfunction should be considered in combination with multiple sensory, motor and diminished reflexes as this could indicate cauda equina syndrome, large lumbar disc, etc.

Prevalence of Sacroiliac Pain, a Type of Pelvic Girdle Pain[edit | edit source]

Between 5 – 10% of people develop chronic low back pain worldwide. This leads to[16]:

- High treatment costs

- Extended periods of sick leave

- Individual suffering

- Invasive interventions such as surgeries

- Disability

Sacroiliac pain, a type of pelvic girdle pain, has been known to be undiagnosed or mistreated in people with low back pain. It is estimated to occur in 10-30% of persons with non-specific low back pain[17]. Some studies have found this incidence even higher.

In a 2013 study by Visser et al.,[18] 40 percent of the study population had a sacroiliac joint or sacroiliac joint and disc component. Visser et al.[18] noted that lumbar nerve root compression can mimic sacroiliac joint radiculopathy and thorough evaluations of the spine, hips and sacroiliac joint should be done to get an accurate diagnosis.

Prevalence of Pregnancy-Related Lumbar Back Pain (PLBP) and Pelvic Girdle Pain[edit | edit source]

- 56% to 72% of the antepartum population[19][20]

- 20% of antepartum population report severe symptoms during 20 -30 weeks of gestation[19][20]

- 7% of women with pelvic girdle pain will experience lifelong problems[19][20]

- 33% to 50% of pregnant females report PGP before 20 weeks of gestation and prevalence may reach 60 to 70% in late pregnancy[21]

Considering this high prevalence, it is evident that pelvic girdle pain remains a significant problem globally. There is, however, no gold standard testing protocol[22]; currently various combinations of provocation tests and imaging are used in research to diagnose pelvic girdle pain.[23] Physiotherapists are best placed to offer and provide individuals with guidance and help in this area.[11] Further research is needed to guide physiotherapy interventions.[11]

Risk Factors for Pelvic Girdle Pain[edit | edit source]

Clinton et al. (2017) list the following risk factors based upon strong evidence[8]:

- Prior history of pregnancy

- Orthopaedic dysfunctions

- Increased body mass index (BMI)[24]

- Smoking

- Work dissatisfaction

- Lack of belief in improvement in the prognosis of pelvic girdle pain

They also list these risk factors that might lead to the development of pelvic girdle pain[8]:

- Joint hypermobility

- History of multiparity (i.e have had more than one child)

- Periods of amenorrhea

- Hip and/or lower extremity dysfunction including the presence of gluteus medius and pelvic floor muscle dysfunction

- History of trauma to the pelvis

- History of low back pain and/or PGP, especially in previous pregnancies

In pregnancy, Ceprnja et al.[25] note that a history of low back pain and/or pelvic girdle pain and a family history of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain. is associated with pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain was consistent with previous studies.

Risk Factors for Persistent Pelvic Girdle Pain Postpartum[edit | edit source]

In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis the following risk factors for persistent pelvic girdle pain postpartum have been identified[26]:

- History of low back pain

- BMI more than 25 pre-pregnancy

- Pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy

- Depression in pregnancy

- Heavy workload in pregnancy

Clinical Presentation of Pelvic Girdle Pain[edit | edit source]

The clinical presentation varies from patient to patient and can also change over the course of a pregnancy.

Subjective History[edit | edit source]

Symptoms indicative of PGP as described by Clinton et al (2017) based on the European Guidelines:[8][edit | edit source]

- Pain experienced between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal fold, particularly in the area of the sacroiliac joint (SIJ)

- The pain may radiate in the posterior thigh

- Pain can occur in conjunction with/or separately from pain in the pubic symphysis

Pain[edit | edit source]

- The onset of pain may occur around the 18th week of pregnancy and may reach peak intensity between the 24th and 36th week of pregnancy[27]

- Pain resolves by the 3rd month postpartum[27]

- Pain experienced between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal fold, particularly in the vicinity of the sacroiliac joints (SIJ) and/or the pubic symphysis[7]

- Pain can be local or local with radiculopathy

- Fortin’s area – a rectangular area that runs from the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) 3 cm lateral and 10 cm caudal[28]

- One finger method - the person will often use one finger to point to the painful area, usually within this rectangular area[28]

- Radicular component of sacroiliac pain – initially it was thought that radicular pain past the knee is not related to SIJ dysfunction but Fortin et al.[29] showed that radicular pain from the SIJ can go past the knee and that it can be a cause of SIJ dysfunction. Visser et al.[18] also reported a combination of SIJ and disc-related radicular pain

- Pain may be described as stabbing, dull, shooting or burning sensation[30]

- Pain intensity on Visual Analogue Scale averages around 50 -60mm[31]

- Differentiation between PGP and PLBP – useful to use a patient pain distribution diagram[8]

- PGP – located under the PSIS in the gluteal area, the posterior thigh and the groin (specifically over the pubic symphysis)

- PLBP – concentrated in the lumbar region, above the sacrum

Functional Complaints[edit | edit source]

Issues with transitional movements such as[19][32]:

- Difficulty getting out of a car

- Difficulty getting up or out of the chair

- Difficulty with mobility

- May have difficulty with stairs

- May have difficulty with walking

- Difficulty standing for 30 minutes or longer

- Difficulty with standing on one leg – failed load transfer – going from one leg to another

- Difficulty turning over in bed - often the worst symptom

- Decreased ability to do housework

- Pain/discomfort with weight-bearing activities

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Bergström et al.[34] investigated pregnancy-related low back pain and pelvic girdle pain 14 months after pregnancy. A cohort of 639 women with pregnancy-related back pain or pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy were included in the study. The participants completed questionnaires on pain status and self-rated health and family situations. Follow-up was done 6 months after the initial assessment and of the 639 participants, 200 participants reported having postpartum low back pain or pelvic girdle pain. Another follow-up was completed 14 months after and of the 200 that reported pain after 6 months, 176 completed the questionnaires. Of these participants, 19.3% were in remission and 75.3% reported experiencing recurrent low back pain. At 40 months after the initial assessment, 15.3% of participants reported continuous low back and pelvic girdle pain.[34]

In a long-term follow-up study, Bergstrom et al.[3] reported that 40.3% of the study participants reported pain to various degrees. The following factors were identified as being associated with a statistically significant increase in the odds of reporting pain 12 years postpartum:[3]

- Increased duration of pain and/or persistency of pain

- How participants self-rated their health

- The prevalence of sciatica, neck and/or thoracic spinal pain

- Sick leave within the past 12 months

- Treatment sought

- Use of prescription and/or non-prescription medication

Bergstrom et al.[3] concluded that for a subgroup of women with pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain, spontaneous recovery with no recurrences is unlikely. The strongest predictors of poor long-term outcome were:[3]

- Persistency and/or duration of pain syndromes

- Widespread pain - this may also contribute to long-term sick leave and disability pension

The development of a screening tool to identify women at risk of developing pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain is needed in order to enable early intervention.[3]

Wuytak et al.[35] conducted a systematic review and identified potential prognostic factors for up to one year postpartum. Only three studies were included in the final review and the quality of evidence for all the factors was rated as low or very low. This could be attributed to the lack of replication, with none of the factors being investigated in more than one study. Considering the uncertainty about the results and the inherent susceptibility to bias the following prognostic factors have been identified in women who are less likely to recover 12 weeks postpartum:[35]

- History of low back pain

- Pain in three to four pelvic locations

- Overweight

- Six months postpartum, pelvic girdle pain is more likely to persist in:

- Use of crutches during pregnancy by an individual

- Severe pain in all three pelvic locations during pregnancy

- Presence of other pain conditions

- Obesity

- Younger age of menarche

- History of previous low back pain

- High co-morbidity index

- Smoking – conflicting evidence

- Mode of birth in the subgroup of women who had to use crutches during pregnancy, with women who had instrumental birth or cesarean section more likely to have persistent (severe) PGP

- Emotional distress during pregnancy

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Ceprnja D, Chipchase L, Liamputtong P, Gupta A. "This is hard to cope with": the lived experience and coping strategies adopted amongst Australian women with pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022 Feb 2;22(1):96.

- ↑ Beales D, Hope JB, Hoff TS, Sandvik H, Wergeland O, Fary R. Current practice in management of pelvic girdle pain amongst physiotherapists in Norway and Australia. Manual therapy. 2015 Feb 1;20(1):109-16.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Bergström C, Persson M, Nergård KA, Mogren I. Prevalence and predictors of persistent pelvic girdle pain 12 years postpartum. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2017 Dec 1;18(1):399.

- ↑ Vøllestad NK, Stuge B. Prognostic factors for recovery from postpartum pelvic girdle pain. Eur Spine J. 2009;18(5):718-726. doi:10.1007/s00586-009-0911-2

- ↑ Oslo universitetssykehus. Pelvic Girdle Pain - Explained by FORMI. Published on 21 June 2019. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AmDxtQtJV_0. (last accessed 12 August 2020)

- ↑ Bergström C, Persson M, Mogren I. Pregnancy-related low back pain and pelvic girdle pain approximately 14 months after pregnancy–pain status, self-rated health and family situation. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2014 Dec 1;14(1):48.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Vleeming A, Albert HB, Östgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. European Spine Journal. 2008 Jun 1;17(6):794-819.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 Clinton SC, Newell A, Downey PA, Ferreira K. Pelvic girdle pain in the antepartum population: physical therapy clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health from the section on women's health and the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Women's Health Physical Therapy. 2017 May 1;41(2):102-25.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Vermani E, Mittal R, Weeks A. Pelvic girdle pain and low back pain in pregnancy: a review. Pain Practice. 2010 Jan;10(1):60-71.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Palmer E, Redavid L. Pelvic Girdle Pain: an Overview. Richman S, ed. CINAHL Rehabilitation Guide. Published online August 2, 2019

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Deborah Riczo. Recognising Pelvic Girdle Pain. Course. Plus. 2020

- ↑ Koes BW, Van Tulder M, Lin CW, Macedo LG, McAuley J, Maher C. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. European Spine Journal. 2010 Dec 1;19(12):2075-94.

- ↑ Gutke A, Östgaard HC, Öberg B. Predicting persistent pregnancy-related low back pain. Spine. 2008 May 20;33(12):E386-93.

- ↑ Boissonnault WG, Boissonnault JS. Transient osteoporosis of the hip associated with pregnancy. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2001 Jul;31(7):359-67.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 15.8 Tibor LM, Sekiya JK. Differential diagnosis of pain around the hip joint. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2008 Dec 1;24(12):1407-21.

- ↑ Meucci RD, Fassa AG, Faria NM. Prevalence of chronic low back pain: systematic review. Revista de saude publica. 2015 Oct 20;49:73.

- ↑ Booth J, Morris S. The sacroiliac joint–Victim or culprit. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2019 Feb 1;33(1):88-101.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Visser LH, Nijssen PG, Tijssen CC, Van Middendorp JJ, Schieving J. Sciatica-like symptoms and the sacroiliac joint: clinical features and differential diagnosis. European Spine Journal. 2013 Jul 1;22(7):1657-64.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Wu WH, Meijer OG, Uegaki K, Mens JM, Van Dieen JH, Wuisman PI, Östgaard HC. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (PPP), I: Terminology, clinical presentation, and prevalence. European Spine Journal. 2004 Nov 1;13(7):575-89.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Mens JM, Huis YH, Pool-Goudzwaard A. Severity of signs and symptoms in lumbopelvic pain during pregnancy. Manual therapy. 2012 Apr 1;17(2):175-9.

- ↑ Robinson HS, Mengshoel AM, Veierød MB, Vøllestad N. Pelvic girdle pain: potential risk factors in pregnancy in relation to disability and pain intensity three months postpartum. Manual therapy. 2010 Dec 1;15(6):522-8.

- ↑ Riczo D. Recognising Pelvic Girdle Pain Course. Plus, 2021.

- ↑ Thawrani DP, Agabegi SS, Asghar F. Diagnosing Sacroiliac Joint Pain. JAAOS - Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2019;Publish Ahead of Print.

- ↑ Stendal Robinson H, Lindgren A, Bjelland EK. Generalized joint hypermobility and risk of pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy: does body mass index matter? Physiother Theory Pract. 2022 Dec;38(12):2222-9.

- ↑ Ceprnja D, Chipchase L, Fahey P, Liamputtong P, Gupta A. Prevalence and factors associated with pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy in Australian women: a cross-sectional study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2021 Jul 15;46(14):944-9.

- ↑ Wiezer M, Hage-Fransen MA, Otto A, Wieffer-Platvoet MS, Slotman MH, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW, Pool-Goudzwaard AL. Risk factors for pelvic girdle pain postpartum and pregnancy related low back pain postpartum; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice. 2020 May 5:102154.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Kanakaris NK, Roberts CS, Giannoudis PV. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: an update. BMC medicine. 2011 Dec 1;9(1):15.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Fortin JD, Falco FJ. The Fortin finger test: an indicator of sacroiliac pain. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF ORTHOPEDICS-BELLE MEAD-. 1997 Jul;26:477-80.

- ↑ Fortin JD, Vilensky JA, Merkel GJ. Can the sacroiliac joint cause sciatica?. Pain physician. 2003 Jul;6(3):269-72.

- ↑ Sturesson B, Uden G, Uden A. Pain Pattern in Pregnancy and" Catching" of the Leg in Pregnant Women With Posterior Pelvic Pain. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 1998 Mar 1;53(3):136-7.

- ↑ Kristiansson P, Svärdsudd K, von Schoultz B. Back pain during pregnancy: a prospective study. Spine. 1996 Mar 15;21(6):702-8.

- ↑ Nielsen LL. Clinical findings, pain descriptions and physical complaints reported by women with post‐natal pregnancy‐related pelvic girdle pain. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2010 Sep;89(9):1187-91

- ↑ PregActive. Pelvic Girdle Pain – Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment. Published on 5 August 2018. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TpofUYC3ePs. (last accessed 12 August 2020)

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Bergström C, Persson M, Mogren I. Pregnancy-related low back pain and pelvic girdle pain approximately 14 months after pregnancy–pain status, self-rated health and family situation. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2014 Dec 1;14(1):48.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Wuytack F, Daly D, Curtis E, Begley C. Prognostic factors for pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain, a systematic review. Midwifery. 2018 Nov 1;66:70-8.