Psychological Approaches to Pain Management: Difference between revisions

Scott Buxton (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Scott Buxton (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

=== Pain as a reflection on the Current State of a Persons Tissues === | === Pain as a reflection on the Current State of a Persons Tissues === | ||

In the simplest evolutionary description pain is used to tell us that something is wrong or has been damaged and we need to change what we are doing<ref name="Sci">The Science Museum. Why do we feel pain? [ONLINE] Accessed on 20/03/2014 http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/whoami/findoutmore/yourbrain/whatareyoursenses/whereareyou/whydowefeelpain.aspx</ref>. Effectively it is a protective mechanism to extend life and a crude for of learning from our mistakes. However this can go wrong and this 'Simple Mechanism' can develop into a more sinister and incorrect self-perpetuating cycle of chronic pain. There are a number of different ways the pain mechanism can go wrong. | |||

The work of [http://www.bodyinmind.org/who-are-we/ Lorimir Moseley] and others have helped develop our knowledge of chronic pain and developed our understanding of pain from a biopsychosocial perspective. | |||

<br> | |||

In Moseleys' paper [http://www.specialistpainphysio.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/Reconceptualising-Pain-2007.pdf RECONCEPTUALISING PAIN ACCORDING TO MODERN PAIN SCIENCE] he argues several points<ref name="Moseley">RECONCEPTUALISING PAIN ACCORDING TO | |||

MODERN PAIN SCIENCE. Moseley L. Physical Therapy Reviews 2007; 12: 169–178</ref> | |||

#'''That pain does not provide a measure of the state of the tissues''' | |||

This can be argued because of the nature of early experiments attempting to measure pain only measuring simple observational behaviours such as a reflex or a more complex variable such as the amount of time spent in a non-preferred environment. These only show that a noxious stimulation changes behaviour and that neither behaviour or nerve activity explicitly explain or give you the true state of the tissues<ref name="Moseley" />. This is complicated further when the responses of different nerve fibres are measured as the complex nature of each nerve and their interlinking nature means it is very challenging to explain their relationship and influence on tissues. | |||

2. '''That pain is modulated by many factors from across somatic, psychological and social domains''' | |||

Some examples of psychological or social situations overcoming the effects of pain can be seen in the world of cycling. In the 2013 Tour de France British Cyclist Geraint Thomas was involved in a crash on stage one which resulted in a fractured pelvis as well as a large amount of soft tissue injury, 3 weeks later he completed the tour de france<ref name="TdF">Beaven C. Hayles, R. Tour de France 2013: Geraint Thomas pain must be horrendous [ONLINE] Accessed 20/03/2104 available from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/0/cycling/23147621</ref>. Other sporting examples include Tiger Woods who won the 2008 US Open with a torn ligament in his left knee and a double stress fracture in the same leg or MotoGP world champion Jorge Lorenzo who rode a a race and finish fifth despite undergoing surgery on a broken collarbone the day previously<ref name="Tdf" />. This ability to endure extreme pain through psychological determination in conjunction with limited medications available to elite sportsmen (due to fear/risk of a doping ban) has been studied by many researchers and has been summarised by Fields et al<ref name="Fields">Fields H, Basbaum A, Heinricher M. CNS mechanisms of pain modulation. In: McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M. (eds)Textbook of Pain, 5th edn. London: Elsevier, 2006; 125–43</ref>. These findings is yet more evidence to show that pain is not simplistic or simply controlled or experienced by somatic mechanisms alone. | |||

3. '''That the relationship between pain and the state of the tissues becomes less predictable as pain persists''' | |||

4. '''That pain can be conceptualised as a conscious correlate of the implicit perception that tissue is in danger''' | |||

= Assessment Considerations = | = Assessment Considerations = | ||

Revision as of 21:47, 20 March 2014

This article or area is currently under construction and may be partially completed. Please come back soon to see the finished work!. (17 May 2024)

Original Editor - Scott Buxton

Top Contributors - Scott Buxton, Admin, Evan Thomas, Lauren Lopez, Kim Jackson, Vidya Acharya, 127.0.0.1, WikiSysop and Tolulope Adeniji

Pain Management[edit | edit source]

What is Pain Management?[edit | edit source]

Pain management is an area of modern medicine which utilises the multi-disciplinary team to help ease the pain and suffering of patients living with long-term pain to improve their quality of life[1]. Medicine is usually the first port of call to manage pain, however, when pain in not responsive to medication, or resistant to treatment, or persists after healing has occurred and an exact cause of the pain has not been found alternative treatment or a combined approach can be used[2].

The alternative to medicine or combined approaches to pain management are broad and each of which can be based upon different paradigms of understanding pain. The different approaches come from the wide range of healthcare professionals unique treatments towards pain management, not only limited to Mental-Health or Psychiatrists but can include Physiotherapists, Occupational Therapists, Nurse Practitioners, Medics, Nuse Specialists and Massage Therapists.

Different Types of Management/Treatment[edit | edit source]

The techniques these professionals use can be and not limited to: (This list is not exhaustive and please add more!)

- Patient Education

- Operant Conditioning Approaches

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

- Distraction

- Classical Conditioning Approaches

- Social Support Methods

- Relaxation Methods

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- Hypnosis

- Biofeedback

What is the Psychological Approach to Pain Management[edit | edit source]

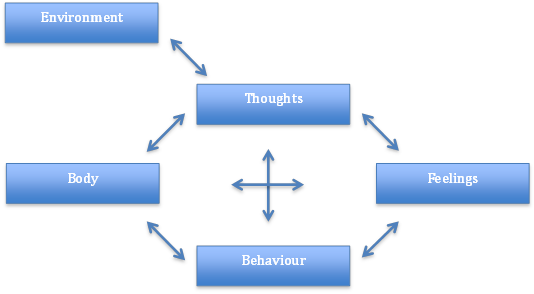

As well as the neural interactions and links the brain goes through when a person is in pain, there are multiple layers of complex abstract thoughts and feelings a person goes through which culminates how much pain a person feels and how they deal with pain. Their cognitive constructs, behavioural constructs and environmental influences are all intertwined in a complex web of individuality which need to be considered and incorporated into any treatments for them to be effective and are found out during an initial assessment[3]. It is these personal, individual and holistic areas which make it a pscyhological approach sitting within the biopsychosocial model of patient treatment.

The Difference Between Acute and Chronic Pain[edit | edit source]

Previously pain used to fit into the biomedical model with a reductionist view (i.e Pain was derived from a specific physical pathology) and catagorically dismissed social, psychological and behavioural mechanisms as irrelevent and of no importance to understanding pain[3]. This is grossly oversimplified and now we understand that pain is more than a simple response to a physical stimulus and in recent years several models of pain models have been created to explain and develop our understanding of pain.

Acute pain can be defined as:

the normal, predicted physiological response to an adverse chemical, thermal or mechanical stimulus… associated with surgery, trauma and acute illness[4].

As the definition states, acute pain is a predicted response to a stimulus. If you have had surgery to repair and fractured hip, there will be a usual pattern of pain and rate of recovery based upon the patients demographics. However to take this definition further one could say that pain is:

a complex perceptual phenomenon that involves a number of dimensions, including, but not limiting to, intensity, quality, time course and personal meaning[5].

This definition incorporates the modern thinking of pain, not just acute pain but pain as a whole. The first definition is still true in the fact that acute pain is predictable and does follow a pattern but the second quote reflects the more complex nature of pain and is a reminder that pain should not be thought of as the same for all patients. It becomes even more complex when pain changes from the predictable pattern of duration and nature to an unpredictable and unexplained phenomenon that exceeds the usual duration of healing and becomes chronic.

Chronic pain can be defined as when:

pain persists for 3 months or longer, it is considered chronic[6] and, while not necessarily maladaptive[7][8], often leads to physical decline, limited functional ability and emotional distress.

Although this quote only gives the time duration there are many others which consider chronic pain to be unexplained, irregular, unique and incredibly dependent upon the individuals personal beliefs and coping strategies and it is this chronic pain which is subject to a large amount of study and psychological management strategies. This is in part due to the impact it has on healthcare systems worldwide, for example common chronic pain problems cost the U.S.A US$60 billion per year[3] and in the UK somewhere in the region of £5 billion per year[9] and there are millions of lost work days throughout the world subsequently it is a crucial area in which treatment and management is continually being developed.

Key Models to Understand Pain[edit | edit source]

Pain Gate Theory[edit | edit source]

The pain gate theory (PGT) was first proposed in 1965 by Melzack and Wall[10], and is a commonly used explanation of pain transmission, it was one of the first models to incorporate biological and psychological mechanisms within the same model[3]. Thinking of pain theory in this way is very simplified and may not be suitable in some contexts, however when discussing pain with patients this description can be very useful.

In order to understand the PGT, the sensory nerves need to be explained. At its most simple explanation there are 3 types of sensory nerves involved of transmission of noxious stimuli[11].

- α-Beta fibres - Large diameter and myelinated - Sharp pain - Faster

- α-Delta fibres - Small diameter and myelinated - Vibration and light touch - Fast

- C fibres - Small diameter and un-myelinated - Throbbing or burning - Slow

The size of the fibres is an important consideration as the bigger a nerve is the quicker the conduction, additionally conduction speed is also increased by the presence of a myelin sheath, subsequently large myelinated nerves are very efficient at conduction. This means that α-Beta fibres are the quickest of the 3 types followed by α-Delta fibres and finally C fibres[12].

The interplay between these nerves is important but it is not the whole story, as you can see only two of these nerves are pain receptors α-Delta fibres are purely sensory in terms of touch. All of these nerves synapse onto projection cells which travel up the spinothalamic tract of the CNS to the brain where they go via the thalamus to the somatosensory cortex, the limbic system and other areas[13]. In the spinal cord there are also inhibitory interneurons which act as the 'gate keeper'. When there is no sensation from the nerves the inhibitory interneurons stop signals travelling up the spinal cord as there is no important information needing to reach the brain so the gate is 'closed'[10]. When the smaller fibres are stimulated the inhibitory interneurons do not act, so the gate is 'open' and pain is sensed. When the larger α-Delta fibres are stimulated they reach the inhibitory interneurons faster and, as larger fibres inhibit the interneuron from working, 'close' the gate. This is why after you have stubbed your toe, or bumped your head, rubbing it helps as you are stimulating the α-Delta fibres which close the gate[10].

In addition to the idea of the different nerve types influencing whether or not the gate is open or not, mood and cognition also influence the status of the gate in a "Top Down" fashion influencing the perception of the pain further[14].

For an alternate explanation: Pain Gate Theory Article Science Daily Physiotherapy Journal Article: Pain Theory & Physiotherapy

This model was the first to challenge the long held assumptions of a biomedical approach to managing pain, and advancements in understanding of anatomy, neurology and cognition have led to models fully incorporating the biopsychosocial model contemplating the reciprocal nature of mood and cognition on pain and vice versa.

Biopsychosocial Models of Pain[edit | edit source]

There are a large number of different models to contemplate and only a few will be discussed here, links and references to others will be provided here.

The biopsychosocial approach holds that the experience of pain is determined by the interaction between biological, psychological (e.g. cognition, behaviour, mood) and social (e.g. cultural) factors[3].

This approach incorporates the view that perception of pain is influenced by the combination and interaction of biological, psychological and social factors (all of which can be broken down into different sub-categories). Not all models incorporate all three aspects, some focus mainly on behaviour such as Fordyce et al. It is important to consider that not one model is correct but that different models have strengths and weaknesses and suit patients on an individual basis.

As with all models there is some difference on opinion with certain respects, such as which aspect has the greatest influence on pain perception, however biopsychosocial models all agree on the central focus; the focus is not on a disease but on the behaviour around the disease, feeding and fueling beliefs and attitude which perpetuates a problem. The central argument, as stated, is illness behaviour which implies that individuals may differ in perception of an response to bodily sensations and changes (e.g. pain, nausea, heart palpitations), and that these differences can be understood in the context of psychological and social processes[3].

Pain as a reflection on the Current State of a Persons Tissues[edit | edit source]

In the simplest evolutionary description pain is used to tell us that something is wrong or has been damaged and we need to change what we are doing[15]. Effectively it is a protective mechanism to extend life and a crude for of learning from our mistakes. However this can go wrong and this 'Simple Mechanism' can develop into a more sinister and incorrect self-perpetuating cycle of chronic pain. There are a number of different ways the pain mechanism can go wrong.

The work of Lorimir Moseley and others have helped develop our knowledge of chronic pain and developed our understanding of pain from a biopsychosocial perspective.

In Moseleys' paper RECONCEPTUALISING PAIN ACCORDING TO MODERN PAIN SCIENCE he argues several points[16]

- That pain does not provide a measure of the state of the tissues

This can be argued because of the nature of early experiments attempting to measure pain only measuring simple observational behaviours such as a reflex or a more complex variable such as the amount of time spent in a non-preferred environment. These only show that a noxious stimulation changes behaviour and that neither behaviour or nerve activity explicitly explain or give you the true state of the tissues[16]. This is complicated further when the responses of different nerve fibres are measured as the complex nature of each nerve and their interlinking nature means it is very challenging to explain their relationship and influence on tissues.

2. That pain is modulated by many factors from across somatic, psychological and social domains

Some examples of psychological or social situations overcoming the effects of pain can be seen in the world of cycling. In the 2013 Tour de France British Cyclist Geraint Thomas was involved in a crash on stage one which resulted in a fractured pelvis as well as a large amount of soft tissue injury, 3 weeks later he completed the tour de france[17]. Other sporting examples include Tiger Woods who won the 2008 US Open with a torn ligament in his left knee and a double stress fracture in the same leg or MotoGP world champion Jorge Lorenzo who rode a a race and finish fifth despite undergoing surgery on a broken collarbone the day previously[18]. This ability to endure extreme pain through psychological determination in conjunction with limited medications available to elite sportsmen (due to fear/risk of a doping ban) has been studied by many researchers and has been summarised by Fields et al[11]. These findings is yet more evidence to show that pain is not simplistic or simply controlled or experienced by somatic mechanisms alone.

3. That the relationship between pain and the state of the tissues becomes less predictable as pain persists

4. That pain can be conceptualised as a conscious correlate of the implicit perception that tissue is in danger

Assessment Considerations[edit | edit source]

According to Asmundson et al[3] an in-depth and thorough assessment is required to discover the root cause of psychological aspects of pain and person specific influence which will be integral to know when it comes to selection and direction of treatment. There are a number of areas which need to be covered in the assessment but arguably the most important is the consideration of the pain intensity, severity and irritability along with location, distribution and duration. This is a useful marker for measuring pain and as a tool for differential diagnosis but asking how the patient is affected functionally is an important consideration but also cruical to confirming the subjective reports of the patient. Tools such as the Visual Analogue Scale, 4-Item Pain Intensity Measure or the Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Another area of consideration are the various "empirically supported and theoretically relevant cognitive, behavioural and environment influences" which are person specific and can aid in assessment and conclusions relevant for treatment[3].

The idea of looking out for cognitive, behavioural and environmental influences ties with the concept of the Flag System which includes Yellow, Blue, Orange, Black and Red flags as universal indicators of how different psychological, and clinical signs can influence treatment outcomes. Head over to the page to find out more about it.

Treatments - Psychological Approach[edit | edit source]

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy[edit | edit source]

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is a method that can help manage problems by changing the way patients would think and behave. It is not designed to remove any problems but help manage them in a positive manner[19] [20].

Here is a brief history of CBT, as written by Rachael Lowe found here Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

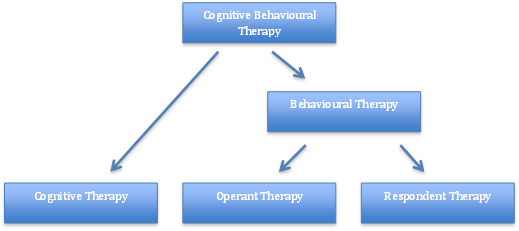

Behaviour therapy (BT) was developed in the 1950’s independently in three countries: South Africa, USA and England [21]. It was further developed to Cognitive Therapy (CT) in the 1970’s by Dr Aaron Beck with its main application on people with depression, anxiety and eating disorders [19] [22]. However, the main evidence today focuses on CBT, after the merging of BT and CT in the late 80’s [23].

Below is a breakdown of the different aspects of CBT as a concept incorporating its namesake; both cognitive and behavioural elements. These elements can be taken further and take into account two of the most important theories to a behaviourist: operant and classical (respondent) conditioning.

Fig.2 - Breakdown of CBT theory

CBT assumes that changing maladaptive thinking leads to change in behavior. Therapists help individuals challenge their patterns and beliefs and replace "errors in thinking such as overgeneralizing, magnifying negatives, minimizing positives and catastrophizing" with more realistic and effective thoughts, decreasing emotional distress and self-defeating behavior. By challenging an individual's way of thinking and the way that he/she reacts to certain habits or behaviors in a constructive manner can create cognitive dissonance and therefore an opportunity to alter someones thinking patterns and behaviour[24]. Put simply CBT helps you think positively, realistically and rationally about a situation, for example here is a scenario fron the Royal College of Pscyhiatrists (Website)[25]:

You've had a bad day, feel fed up, so go out shopping. As you walk down the road, someone you know walks by and, apparently, ignores you. This starts a cascade of:

| Unhelpful | Helpful | |

| Thoughts: | He/She ignored me - they dont like me | He/She looks wrapped up in themselves - I wonder if there is something wrong? |

| Emotional Feelings: | Low, Sad and Rejected | Concerned for the other person, positive |

| Physical: | Stomach cramps, low energy, feel sick | None- feel comfortable |

| Action: | go home and avoid them | Get in touch to make sure they are ok |

According to the Royal College of Psychiatrists this can be a typical CBT session[25]:

- You will usually meet with a therapist for between 5 and 20, weekly, or fortnightly sessions.

- Each session will last between 30 and 60 minutes.

- You and the therapist will usually start by agreeing on what to discuss that day.

- With the therapist, you break a / each problem down into its separate parts. To help this process, your therapist may ask you to keep a diary. This will help you to identify your individual patterns of thoughts, emotions, bodily feelings and actions.

- Together you will look at your thoughts, feelings and behaviours to work out if they are unrealistic or unhelpful and how they affect you.

- The therapist will then help you to work out how to change unhelpful thoughts and behaviours.

- It's easy to talk about doing something, much harder to actually do it. So, after you have identified what you can change, your therapist will recommend 'homework' - you practise these changes in your everyday life.

CBT has six phases[24]:

Assessment or psychological assessment;

Reconceptualization;

Skills acquisition;

Skills consolidation and application training;

Generalization and maintenance;

Post-treatment assessment follow-up.

The reconceptualization phase makes up much of the "cognitive" portion of CBT.

A simplisitc and broad understanding of the CBT model and cycle are shown below.

Fig.3 - Factors involved within the Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Model

In terms of clinical relevance CBT has been the subject of many different studies, the majority of which are not within a physiotherapists scope of practice such a substance abuse, child abuse, schizophrenia and personality disorders however as the theory develops and our profession grows it is becoming more clinically relevant. Areas such as musculoskeletal outpatients can use specially trained therapists to treat fibromyalgia[26], low back pain[24] and chronic pain.

Here is a link to a list of Cochrane Reviews including the phrase "Cognitive Behavioural Therapy"

Reconceptualising Pain[edit | edit source]

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Additional Key Resources

[edit | edit source]

Additional Biopsychosocial Models of Understanding Pain[edit | edit source]

The Behavioural Management of Chronic Pain by Fordyce[27]

A New Clinical Model for the Treatment of Low Back Pain. by Waddell[28].

Pain and Behavioural Medicine: A Cognitive-Behavioural Perspective. By Turk

Other Physio-Pedia Pages[edit | edit source]

Pain Course Pain Assessment Cognitive Behavioural Therapy All Physio-Pedia pages with PAIN as their category.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Hardy, Paul A. J. (1997). Chronic pain management: the essentials. U.K.: Greenwich Medical Media

- ↑ Butler DS, Moseley GL. Explain pain. Adelaide: Noigroup Publications; 2003

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Asmundson,G. Gomez-Perez,L. Richter, A. Carleton, RN. The psychology of pain: models and targets for comprehensive assessment. Chapter 4 in Hubert van Griensven’s Pain: A text book for health care professionals. Elsevier, 2014.

- ↑ Federation of State Medical Boards of the United States .Model guidelines for the use of controlled substances for the treatment of pain. The Federation, Euless, TX (1998)

- ↑ Merskey, H., Bogduk, N., 1994.fckLRClassification of chronic pain:fckLRdescriptions of chronic painfckLRsyndromes and definitions of painfckLRterms, second ed. IASP Press, Seattle

- ↑ International Association for the study of Pain (IASP). Classification of Chronic Pain, Second Edition (Revised). 2011. [ONLINE] Available from http://www.iasp-pain.org/PublicationsNews/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1673;navItemNumber=677

- ↑ Asmundson, G.J.G., Norton, G.R.,Allerdings, M.D., et al., 1998. Posttraumatic stress disorder and work-related injury. J. Anxiety Disord. 12, 57–69

- ↑ Turk, D.C., Rudy, T.E., 1987. IASP taxonomy of chronic pain syndromes: Preliminary assessment of reliability. Pain 30, 177–189

- ↑ The British Pain Society. FAQs. [ONLINE] Accessed 13/03/2014 available from http://www.britishpainsociety.org/media_faq.htm

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain Mechanisms: A New Theory. Science: New Series 150. (1965:971-979)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Fields HL and Basbaum AI. Central Nervous System Mechanisms of Pain Modulation. in Wall PD and Melzack R (eds). Textbook of Pain. 1999: 309-330 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Fields" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Jenkins G. Kemnitz C. Tortora G. Anatomy and Physiology: From Science to Life. New Jersey :John Wiley sons, Inc 2007

- ↑ Martini, FH. Nath, JL. Fundamentals of Anatomy Physiology. (8th edn). San Francisco:Pearson. 2009

- ↑ Melzack, R., Casey, K.L., 1968. Sensory, motivational and central control determinants of pain. In: Kenshalo, D.R. (Ed.), The Skin Senses.fckLRCC Thomas, Springfield, IL, 423–439.

- ↑ The Science Museum. Why do we feel pain? [ONLINE] Accessed on 20/03/2014 http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/whoami/findoutmore/yourbrain/whatareyoursenses/whereareyou/whydowefeelpain.aspx

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 RECONCEPTUALISING PAIN ACCORDING TO MODERN PAIN SCIENCE. Moseley L. Physical Therapy Reviews 2007; 12: 169–178

- ↑ Beaven C. Hayles, R. Tour de France 2013: Geraint Thomas pain must be horrendous [ONLINE] Accessed 20/03/2104 available from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/0/cycling/23147621

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedTdf - ↑ 19.0 19.1 Beck, J., 1995. Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond. Guildford Press: New York

- ↑ NHS Choices, 2012. Cognitive behavioural therapy. [online] Available at:http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/cognitive-behavioural-therapy/Pages/Introduction.aspx[Accessed 8th Jan 2014]

- ↑ Öst, L.G., 2008. Efficacy of the third wave of behavioral therapies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behaviour research and therapy, 46(3): 296–321

- ↑ Hayes, S.C., 2004. Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behavior Therapy, 35: 639–665

- ↑ Roth, A., Fonagy, P. “What works for whom? A critical review of psychotherapy research”. 2nd ed. Guilford Press: New York 2005

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Gatchel, Robert J.; Rollings, Kathryn H. (2008). "Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with cognitive behavioral therapy". The Spine Journal 8 (1): 40–4.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Cognitive Behavioural Therapy. RCPSYCH [ONLINE] Accessed from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mentalhealthinformation/therapies/cognitivebehaviouraltherapy.aspx 19/03/2014.

- ↑ Hassett, Afton L.; Gevirtz, Richard N. (2009). "Nonpharmacologic Treatment for Fibromyalgia: Patient Education, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, Relaxation Techniques, and Complementary and Alternative Medicine". Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America 35 (2): 393–407.

- ↑ Fordyce W. Roberts A. Sternbach R. The behavioural management of chronic pain: A response to critics. Pain 22:2;113-25. 1985.

- ↑ Waddell G. 1987 Volvo award in clinical sciences. A new clinical model for the treatment of low-back pain. Spine. 1987 12;7:632-44