Pes Planus: Difference between revisions

m (Vidya Acharya moved page Pes valgus to Pes Planus: merging pages) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | == Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | ||

[[File: | [[File:Medial arch of the foot.gif|thumb]] | ||

The classification of the pes valgus is based on '''three aspects''': | The classification of the pes valgus is based on '''three aspects''': | ||

Revision as of 07:50, 15 July 2022

Original Editors - Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka

Top Contributors - Yoni Baetens, Derycker Andries, Andeela Hafeez, Lauren Heydenrych, Kim Jackson, Vidya Acharya, Lucinda hampton, Admin, WikiSysop, Rachael Lowe, Oyemi Sillo, Daniele Barilla, 127.0.0.1, Kai A. Sigel, Aminat Abolade, Evan Thomas and Scott Buxton

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Pes planus (or flat foot) is the loss of the medial longitudinal arch of the foot, heel valgus deformity, and medial talar prominence.[1] The arch of the foot comes closer to the ground or makes contact with the ground. The foot arch is a tough, elastic connection of ligaments, tendons, and fascia between the forefoot and the hind foot. The deformity is usually asymptomatic and resolves spontaneously in the first decade of life, or occasionally progresses into a painful rigid form which causes significant disability. At birth everybody has a flat feet and a noticeable foot arch is seen at around the age of three years[2][3]

Pes planus is fairly common in infants, as they are prone to absent arches secondary to ligamentous laxity and lack of neuromuscular control. Additionally infants have a fat pad under the medial longitudinal arch (MLA), protecting the arch in early childhood, making the arch appear flatter. Most children by age 5 o6 have developed normal arches. The majority cases of pes planus in children are flexible i.e. a normal arch without bearing weight, which disappears with weight-bearing. Only a few children fail to develop a normal arch by adulthood. Obesity in children is a risk factor for MLA to collapse in early childhood, and the other risk factors are gender(female), cerebral palsy and syndrome of Down.[4][5][6][7][8][9]

Forms[edit | edit source]

Two forms of pes planus exist:

- Flexible flat foot: When the arch of the foot is intact on heel elevation and non-bearing but disappears on full standing on the foot

- Ridgid flat foot is when the arch is not present in both heel elevation and weight bearing.[10]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Roughly 20% to 37% of the population has some degree of pes planus, With most cases being the flexible variety, majority of these cases are flexible pes planus. It is more common in children (about 20-30% of children with some form of flat feet) with most children going on to develop a normal arch by 10 years old. Genetics play a strong role with it typically running in families.[3][2] Also, older individuals and high BMI are found to have a significant influence on having flat feet.

Etiology/Causes[edit | edit source]

The medial longitudinal arch of the foot normally develops by the age of 5 or 6 as the fat pad in babies is gradually absorbed and balance improves and skilled movements are acquired. In some children, however, the arch fails to develop which may be a result of tightness in the calf muscles, laxity in the Achilles tendon or poor core stability in other areas such as around the hips.[6][11]Over time it may lead to an altered walking pattern, clumsiness, limping after long walks, and pain in the foot, knees or hips. Beside the aforementioned causes for pes valgus, tarsal coalitions, peroneal spasm and vertical talus are common aetiologies during the childhood. It is therefore important that appropriate treatment starts at an early age.[12]

The etiology of flatfoot has several factors implicated. depending on etiology pes planus can be divided into types, namely congenital and acquired[13]. These factors are:

- Talipes equinovarus deformity, ligamentous laxity, foot equinus deformity, tibial torsional deformity, presence of the accessory navicular bone,[14] congenital vertical talus, and tarsal coalition.

- Diabetes[15] and obesity[16] are also probable factors related to pes planus.[17][18][3]

- Foot and ankle injury such as rupture or dysfunction of the posterior tibial tendon

- Genetic malformation such as Down syndrome and Marfan syndrome[10]

- Familial factors[19]

- Arches weakness due to overuse and certain forms of foot condition or injuries

- Some medical conditions such as arthritis, spina bifida, cerebral palsy, Arthrogyroposis, and muscular dystrophy.[20]

- Flat feet can also occur as a result of pregnancy.[21][22]

- Iatrogenic factors such as posterior tibialis tendon (PTT) transfer.[20][23]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

The bony arch of the foot is potentially unstable and is bound together by ligaments. They withstand short-term stresses. Their primary function is to act as sensory end organs, so when stretched, appropriate muscles are reflexively brought into action. Even the most anatomically perfect foot will become rapidly and grossly flat unless it has muscles of good bulk and tone to support it. The physiological fault may lie in the muscle itself or its nervous control:

- Inadequate nervous control: In normal development, a baby has to learn to balance first its head, then its trunk and eventually to balance the whole body on the feet. The difficult art is not required during the early months of life; but sometimes the balancing reflexes fail to develop even after the child has begun to walk. In that event, the arch inevitably collapses with body weight. Myelination of the pyramidal fibers to the foot is incomplete at birth and the plantar responses in babies is extensor. If the infantile flat foot persists into early childhood, the extensor responses may persist too, and it is tempting to assume that balancing cannot be easily learned until myelination is complete.

- Inadequate muscles:

- After illness or enforced recumbency, the muscles may temporarily be weak and the arch consequently falls when walking is resumed.

- A more lasting form of muscle weakness accompanies a generally poor posture.

- The child (often a pre-adolescent girl) presents a familiar flabby contour with head stuck forward, mouth open, chest flat, back rounded and abdomen protuberant.

- The gluteal muscles are concerned largely with posture (Wiles 1949). They help to straighten the hip and knee, and to twist the limb outwards. This twist can not be imparted to the foot which is anchored to the ground, and so the rest of the limb turns outwards relative to the foot. As a result, the arch is lifted and the line of weight corrected only when the glutei work properly.

- Relative inadequacy of muscle is well illustrated by when extra strain is put upon the arch, for example in overweight individuals.

- Prolonged standing is more harmful to the feet than walking because, during walking, the muscles supporting the arch alternately contract and relax which is the best training for a muscle.[5][11]

The calcaneus, navicular, talus, first three cuneiforms, and the first three metatarsals make up the medial longitudinal arch. This arch is supported by posterior tibial tendon, plantar calcanea navicular ligament, deltoid ligament, plantar aponeurosis, and flexor hallucis longus and brevis muscles. Dysfunction or injury to any of these structures may cause acquired pes planus. Also, excessive tension in the triceps surae, obesity, Achilles tendon or calf muscle tightness, ligamentous laxity in the spring ligament, plantar fascia, or other supporting plantar ligaments may result in acquired flat foot.

Rigid pes planus is rare but usually starts from childhood; tarsal coalition, accessory navicular bone, congenital vertical talus, or other forms of congenital hindfoot pathology. are usually the underlying factors.[13]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The classification of the pes valgus is based on three aspects:

- Arch height: The best parameter to characterize medial longitudinal arch structure was found to be a ratio of navicular height to foot length. It is accepted that the flatness of normal children’s feet and their age are inversely proportioned.[4][26]

- Heel eversion angle: Heel eversion or hindfoot valgus is generally accepted as a normal finding in young, newly walking children and is expected to reduce with age. The eversion of the heel has been repeatedly used for determining the posture of the child’s foot. Resting calcaneal stance position is a more recent method. It has guided clinicians in assessment of the child’s foot posture and calcaneal eversion has been suggested to reduce by a degree every 12 months to a vertical position by age 7 years. A vertical heel is optimal for foot function. The average rear foot angle for children from 6 to16 years is 4° (raging from 0 to 9° valgus).[12][4]

- Whether the flat foot structure is rigid or flexible (cf. Jack’s test[11])

Rigid pes valgus, also called congenital pes planovalgus (convex)[6], is often a result of tarsal coalition, which is typically characterized as a painful unilateral or bilateral deformity.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Evaluation should be based on the presentation at clinic.

Pes planus is very common in young children and asymptomatic. In some cases, flat feet can become painful or rigid, which may be a sign of underlying foot pathology, eg tarsal coalition. In adults, pes planus may be an incidental finding. In symptomatic patients, there may be complaints of pain due to strained muscles and connecting tissues in the midfoot, heel, lower leg, knee, hip, and or back. In more advanced changes client may complain of an altered gait pattern. Clients who typically overpronate will be at high risk for ankle sprains from chronic “rolling of the ankle.” Ask the client about the onset of deformity, timing of symptoms, severity of past and current symptoms, history of trauma, family history, surgical history, and past medical history (including hypertension, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, sensory neuropathies, seronegative spondyloarthropathies, and obesity).[2]

Other signs may include:

- Oedema at the medial side of the foot

- Stiffness of one or both arches of the feet

- Contractures of feet and ankle muscles att the lateral compartment

- Uneven distribution of body weight with resultant one-sided wear of shoes leading to further injuries.

- Difficulty in walking[20]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Co-morbidities include but not limited to neurological conditions such as cerebral palsy; genetics e.g downs syndrome, Marfan syndrome or Ehlers Danos; charcot joint; tibialis posterior dysfunction; Obesity; arthropathies;[27] Shprintzen-Goldberg syndrome.[28]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

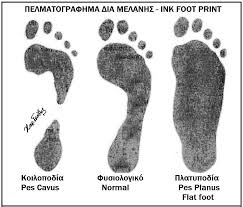

- Footprints: It is still controversial if footprints reflect the real morphology of the medial longitudinal arch. Recent development found an initial correlation between dynamic pressure patterns and static foot-prints.[12]

- X-rays are used to categorise the feet as having normal, slightly flat and moderate arches.

- Foot-posture index (FPI-6)[11]

- Supination resistance test [11][12]: This test is used to estimate the magnitude of pronatory moments. The foot is manually supinated. The higher the force required, the greater the supination resistance and the stronger the pronatory forces. This test is subjective.

- Jack’s test and Feiss angle (are related) [11]: Performing the Jack’s test. The hallux is manually dorsiflexed while the child is standing. If the medial longitudinal arch rises due to dorsiflexion of the hallux, the foot is considered a flexible flat foot. If the medial longitudinal arch remains unchanged, the test designates a rigid flat foot. The purpose of this test is to check the foot flexibility and the onset of the windlass mechanism by tensioning the plantar fascia trough the extension of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. The Feiss line is the line interconnecting malleolus medialis, navicular and first metatarsal head. The inclination of this line with the ground increases when the first metatarsophalangeal joint is dorsiflexed (Jack’s test). This dorsiflexion activates forefoot supination and raises the arch height (140°± 6°).[11]

- Ankle range [11][12]: Children’s ankle range assessment is generally an unreliable measure, as typically assessed when the child is non-weight-bearing. So it is suggested that therapists look at a child’s ability to squat, heel walk and increase stride length.[11]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

The merit of treatment for all flexible flat feet remains ambiguous, with evidence showing that foot orthoses produces improvements in children with pes planus. It remains difficult to conclude if spontaneous physiological arch improvement occurred or the effect of intervention caused the arch improvement.

- There is little evidence for treatment of asymptomatic, flexible, pediatric flat feet in a child who have no underlying medical issues.

- Treatment of symptomatic, flexible flat feet is generally accepted for children with contributory background factors or secondary complications, or if pes planus persists past childhood.

- Evidence supports the use of non surgical interventions for painful pes planus.

- The child should be fitted with a flat, lace-up shoe with a firm heel and MLA support, a broad and deep toe box and the ‘toe break’ at the junction between the anterior third and posterior two-thirds of the shoe.[29]

Treatment is based on etiology and NSAIDS are sufficient for pain.

Surgery is required in rigid pes planus and in cases resistant to therapy to reduce symptoms.[30] Most surgical methods aim at realigning foot shape and mechanics. These surgeries could be tendon transfers, realignment osteotomies, arthrodesis and where other surgeries fail, triple arthrodesis is performed[31]

For the congenital pes valgus treatment, researchers have defined the best possible treatments depending on the age of the person/child.

- In a child younger than 2 years, an extensive release with lengthening of the Achilles tendon and fixation procedure is recommended. It is less invasive than other techniques, because there is no tendon transfer or bony procedures needed. The explanation could be because of the greater adaptability of the cartilaginous structures.

- In a child with neural tube defect, younger than 2 years of age, an extensive release with tendon transfer procedure is recommended. A neuromuscular imbalance between a weak Tibialis Posterior tendon and a strong evertor of the foot could be responsible for this condition. Good results are found for this operation which aims to correct this imbalance.

- In a child older than 2 years of age, an extensive release with tendon transfer procedure is proposed. Surgical correction becomes increasingly difficult in older children because of secondary changes of the bone. This procedure resulted as the best for children whose walking and standing potential has been established.

In case of failure of precedent procedures, a bony procedure may be considered. There are good results for children of 4 years and older with these procedures. Every surgery is usually followed by a plaster cast for two to three months. The recovery after surgery takes about 6 months to 1 year to heal completely and to recover completely on a functional level.[4][5][7]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

The aim of Physical therapy is to minimize pain, increase foot flexibility, strengthen weak muscles, train proprioception, and patient education and reassurance. As part of the assessment process, the physiotherapist can assist in evaluating the gait, gross motor skills and the impact the foot deformity has on functional activities. Assess endurance, speed, fatigability, pain and ability to walk on different terrains, with a focus on assessing function, not just structural abnormalities.

Pain management includes rest, activity modification, cryotherapy, massage, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication. Ultrasound and pulsed electrical stimulation can also be used for pain relief. Electric stimulation will aid blood circulation, promoting healing processes and diminishing discomfort and oedema.

- Flexibility exercises are passive ROM exercise of the ankle and all foot joints; Stretching of gastrocnemius soleus complex and peroneus brevis muscles to facilitate varus and foot adduction; Heel-cord stretch for the Achilles tendon and calf muscles to relief tight heel cord.[32]

- Strengthening Exercises:

- Strengthening exercises are given to anterior and posterior tibialis muscles and the flexor hallucis longus, Intrinsic, interosseus plantaris muscles, and the abductor hallucis to prevent valgus and flattening of the anterior arch. Arch muscle strengthening exercise with theraband

- Global activation of the muscles known to support the medial longitudinal arch and the varus with and without resistance.

- Single leg weight bearing

- Toe walking

- For Proprioception, Toe and heel walking, Single leg weight bearing, and Descending an inclined surface are exercises that could be prescribed. Also, Toe clawing of towel and pebbles, forefoot standing on a stair, toe extension and toe fanning/spreading, and heel walking are all good exercises to maintain viable foot arches.

- Counselling on proper footwear, recommendation on motion control shoes, orthotics and braces are also needed. Foot orthotics such as shoe inserts are used to support the arch for foot pain secondary to pes planus alone or combination with leg, knee, and back pain.

- Obese and overweight individuals should be counseled on weight loss through exercise and dieting; Possibly refer to a dietician for appropriate insight.

- Other co-morbidities amenable to physiotherapy can also be treated following a proper examination and treatment plan[33][34][13].[31]

- For children with pes planus treatment includes: [6][7]

- Advice on appropriate footwear. [4][11]

- Advice on appropriate insoles to improve foot position and referral to an podiatrist and an orthotist: in-shoe wedging, foot splints, night stretch splints and cast orthoses. The primary action splint therapy is aimed at stabilising the rear foot and midfoot but not blocking the forefoot. Age-expected foot position, stance and gait are dynamic considerations and need to be well understood. [11]

- Reducing pain and risk of secondary joint problems. [4][6][12].

- Providing an exercise program to increase strength in the muscles that stabilise the arches. Examples being: walking up on tip-toes; walking on the heels; activities to improve the dynamic arch such as walking barefoot on soft sand, flexing the toes (eg picking up a tissue with the toes), rolling a ball under the arch of the foot when seared; encouraging climbing and other gross motor activities. Try to engage the family in the exercise therapy eg incorporating games and activities that can be part of child’s day[29]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Troiano G, Nante N, Citarelli GL. Pes planus and pes cavus in Southern. Annali dell'Istituto superiore di sanita. 2017 Jun 7;53(2):142-5.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Raj MA, Tafti D, Kiel J Pes Planus Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430802/ (accessed 2.7.2022)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Suciati T, Adnindya MR, Septadina IS, Pratiwi PP. Correlation between flat feet and body mass index in primary school students. InJournal of Physics: Conference Series 2019 Jul 1 (Vol. 1246, No. 1, p. 012063). IOP Publishing.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 K.C. Chen, C.J. Yeh, Li-Chen Tung, J.F. Yang, S.F. Yang, C.H. Wang – Relevant factors influencing flatfoot in preschool-aged children - Springer – 2010 A2

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 C.A. Turriago, M. F. Arbela´ez, L.C. Becerra - Talonavicular joint arthrodesis for the treatment of pes planus valgus in older children and adolescents with cerebral palsy – Epos – 2009 A2

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 D.J. Oeffinger, R. W. Pectol Jr., C. M. Tylkowski - Foot pressure and radiographic outcome measures of lateral column lengthening for pes planovalgus deformity – Springer – 2009 A2

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 A.M. Evans – The paediatric flat foot and general anthoropometry in 140 Australian school children aged 7 – 10 years – 2011 A1

- ↑ J.V. Vanore et al – Diagnosis and treatment of adult flat foot A2

- ↑ Raj MA et al. Pes planus Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430802/ (accessed 3.7.2022)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Wilson DJ. Flexible vs Rigid Flat Foot, 2019. Available from: https://www.news-medical.net/health/Flexible-vs-Rigid-Flat-Foot.aspx (Accessed 29 June 2020)

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 Pediatrics – Angela Evans and Ian Mathieson – Elsevier – 2010 A1

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 A. D. Cass, C.A. Camasta - Review of Tarsal Coalition and Pes Planovalgus: Clinical Examination, Diagnostic Imaging, and Surgical Planning – The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery – 2010 A1

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Raj MA, Tafti D, Kiel J. Pes Planus (Flat Feet). StatPearl-NCBI Bookshelf, 2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430802/ (Accessed 29 June 2020)

- ↑ Cheong IY, Kang HJ, Ko H, Sung J, Song YM, Hwang JH. Genetic influence on accessory navicular bone in the foot: a Korean twin and family study. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2017 Jun;20(3):236-41.

- ↑ Cleveland Clinic. 2019. Available from:https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/15961-adult-acquired-flatfoot#:~:text=In%20people%20with%20diabetes%2C%20a,notice%20as%20their%20foot%20collapses. (Accessed 29 June 2020)

- ↑ Harrison W. Pes planus and paediatric obesity. Physiospot, 2015. Available from: https://www.physiospot.com/research/pes-planus-and-paediatric-obesity/ (Accessed 30 June 2020)

- ↑ Buerk AA, Albert MC. Advances in pediatric foot and ankle treatment. Curr Opin Orthop. 2001;12:437-42.

- ↑ Wearing SC, Hennig EM, Byrne NM, Steele JR, Hills AP. Musculoskeletal disorders associated with obesity: a biomechanical perspective. Obesity reviews: an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2006;7(3):239-50.

- ↑ Mosca VS. Flexible flatfoot in children and adolescents. J Child Orthop. 2010;4(2):107–121

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Berlet GC. Pes Planus (Flatfoot). Medscape, 2019. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1236652-overview#a8 (accessed 29 June 2020)

- ↑ Indy Podiatry. Common foot and ankle problems during pregnancy, 2019. Available from: https://indypodiatry.com/your-feet-during-pregnancy/#:~:text=Over%2Dpronation%2C%20or%20flat%20feet,feet)%20leading%20to%20significant%20pain. (accessed 29 June 2020)

- ↑ Conder R, Zamani R, Akrami M. The Biomechanics of Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2019; 4(72):1-17 doi:10.3390/jfmk4040072

- ↑ Pecheva M, Devany A, Nourallah B, Cutts S, Pasapula C. Long-term follow-up of patients undergoing tibialis posterior transfer: Is acquired pes planus a complication? Foot (Edinb). 2018; 34:83-89.

- ↑ Mount Sinai Health Systems. What causes flat foot? Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GPS10HfgYDY [last accessed 29/6/2020]

- ↑ East Coast Podiatry. Flat Feet (Pes Planus) - Georgina Tay, Singapore Podiatrist . Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9tlzxA8o0w0 [last accessed 29/6/2020]

- ↑ H. Wetzenstein – The significance of congenital pes calcaneo-valgus in the origin of pes planovolgus in childhood – Orthopaedic department in Jönköping B

- ↑ Lowth M. Pes Planus (Flat feet). Patient, 2016. Available from: https://patient.info/doctor/pes-planus-flat-feet (Accessed 30 June 2020)

- ↑ Yadav S, Rawal G. Shprintzen-Goldberg syndrome: A rare disorder. Pan African Medical Journal. 2016; 23:227 doi:10.11604/pamj.2016.23.227.7482

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 AJGP A guide to pes plants in childhood Available: https://www1.racgp.org.au/ajgp/2020/may/paediatric-pes-planus (3.7.2022)

- ↑ Henry JK, Shakked R, Ellis SJ. Adult-Acquired Flatfoot Deformity. Foot & Ankle Orthopaedics. 2019; 4(1):1-17 DOI: 10.1177/2473011418820847

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Carr JB, Yang S, Lather LA. Pediatric Pes Planus: A State-of-the-Art Review. Pediatrics. 2016; 137 (3): e20151230. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-1230

- ↑ Blitz NM, Stabile RJ, Giorgini RJ, DiDomenico LA. Flexible pediatric and adolescent pes planovalgus: conservative and surgical treatment options. Clinics in podiatric medicine and surgery. 2010 Jan 1;27(1):59-77.

- ↑ Halimah bt. Hashim. Physiotherapy Management For Flat Foot (Pes Planus). Health Online Unit, Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2019.Available from: http://www.myhealth.gov.my/en/physiotherapy-management-for-flat-foot-pes-planus/ [Accessed 30 June 2020]

- ↑ Allen J, Solan S. Physiotherapy management of paediatric flat feet. Available from: https://www.peacocks.net/_filecache/316/436/892-physiotherapy-management-of-paediatric-flat-feet.pdf (Accessed 30 June 2020)

- ↑ AskDoctorJo. 7 Best Flat Feet Treatments - Ask Doctor Jo. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y6b4GeYY9sg [last accessed 30/6/2020]