Mirror Therapy

Original Editor - Rachael Lowe.

Top Contributors - Admin, Joshua Samuel, Sheik Abdul Khadir, Kim Jackson, Garima Gedamkar, Vanessa Rhule, Scott Buxton, Robin Tacchetti, Jess Bell, Alex Benham, Wendy Walker, WikiSysop, Rishika Babburu, Evan Thomas, Aicha Benyaich and George Prudden

The Mirror Box[edit | edit source]

A mirror box is a box with one mirror in the center where on each side of it, the hands are placed in a manner that the affected limb is kept covered always and the unaffected limb is kept on the other side whose reflection can be seen on the mirror. Mirror therapy was invented by Vilayanur S. Ramachandran to help alleviate the Phantom limb Pain, in which patients feel they still have a pain in the limb even after having it amputated.

Based on the observation that phantom limb patients were much more likely to report paralyzed and painful phantoms if the actual limb had been paralyzed prior to Amputation (for example, due to a brachial plexus avulsion), Ramachandran and Rogers-Ramachandran proposed the "learned paralysis" hypothesis of painful phantom limbs[1][2][3]. Their hypothesis was that every time the patient attempted to move the paralyzed limb, they received sensory feedback (through vision and Proprioception) that the limb did not move. This feedback stamped itself into the brain circuitry through a process of Hebbian learning, so that, even when the limb was no longer present, the brain had learned that the limb (and subsequent phantom) was paralyzed.

To retrain the brain, and thereby eliminate the learned paralysis, Ramachandran and Rogers-Ramachandran[4] created the mirror box. The patient places the good limb into one side, and the stump into the other. The patient then looks into the mirror on the side with good limb and makes "mirror symmetric" movements, as a symphony conductor might, or as we do when we clap our hands. Because the subject is seeing the reflected image of the good hand moving, it appears as if the phantom limb is also moving. Through the use of this artificial visual feedback it becomes possible for the patient to "move" the phantom limb, and to unclench it from potentially painful positions.

In 1999 V.S. Ramachandran and Eric Altschuler published the results of pilot studies on the use of mirrors in the treatment of hemispatial neglect (the inability to see or pay attention to one side of observed space)[5] and hemiparesis after stoke (muscular weakness on one side of the body)[6]. Ramachandran and Altschuler concluded that mirror therapy may be useful in the treatment of these conditions.

Principle of Mirror Therapy[edit | edit source]

Mirror therapy works on the principle of "Mirror Neurons".

Mirror Neurons accounts for about 20% of all the neurons present in a human brain. These mirror neurons are responsible for laterality reconstruction i.e., ability to differentiate between the left and the right side.

When using the Mirror box, these mirror neurons gets activated and helps in the recovery of affected parts.

NOTE: The major difference in the neuronal reorganisation while using a mirror box is that the ipsilateral hemisphere's neurons gives connection to the same side affected limbs rather than the conventional therapies which targets the neuronal reorganization of the contra-lateral hemisphere. [7] [8]

Effectiveness[edit | edit source]

Although the use of mirror therapy has been shown to be effective in some cases there is still no widely accepted theory of how it works. In a 2010 study of phantom limb pain, Martin Diers and his colleagues found that "In a randomized, controlled trial that used graded motor imagery...and mirror training, patients with complex regional pain syndrome or phantom limb pain showed a decrease in pain as well as an improvement in function post-treatment and at the 6-month follow-up. And it was shown that the order of treatment mattered." However, this study found that mirrored imagery produced no significant cortical activity in patients with phantom limb pain and concluded that "The optimal method to alter pain and brain representation, and the brain mechanisms underlying the effects [of] mirror training or motor imagery, are still unclear." [9]

A number of small scale research studies have shown encouraging results, however there is no current consensus as to the effectiveness of mirror therapy. Recent reviews of the published research literature by Moseley [10] and Ezendam [11]concluded that much of the evidence supporting mirror therapy is anecdotal or comes from studies that had weak methodological quality. In 2011 a large scale review of the literature on mirror therapy by Rothgangel[12] summarized the current research as follows:

For stroke there is a moderate quality of evidence that MT [Mirror Therapy] as an additional intervention improves recovery of arm function, and a low quality of evidence regarding lower limb function and pain after stroke. The quality of evidence in patients with complex regional pain syndrome and phantom limb pain is also low. Firm conclusions could not be drawn. Little is known about which patients are likely to benefit most from MT, and how MT should preferably be applied. Future studies with clear descriptions of intervention protocols should focus on standardised outcome measures and systematically register adverse effects[12]

In 2011 Melita Giummarra and Lorimer Moseley published an article on phantom limb pain that summarized current approaches to treating this problem. They concluded that the benefits of mirror therapy appear to be limited to patients who suffer from cramping and muscular-type phantom pain. They stated:

"One randomized controlled trial showed significant treatment effects of mirror therapy; however, there is limited systematic evidence, and the paradigm appears to be counterproductive during early rehabilitation. Pre-existing body representations or maladaptive cortical reorganization may impede the efficacy of this therapy considering, in a once-off treatment, congenital amputees, and those with chronic phantom pain do not activate contralateral sensory and motor cortices during mirror visual therapy[13]."

Stroke[edit | edit source]

Mirror therapy (MT) has been employed with some success in treating stroke patients. Clinical studies that have combined mirror therapy with conventional rehabilitation have achieved the most positive outcomes[14]. However there is no clear consensus as to its effectiveness. In a recent survey of the published research Rothgangel concluded that "In stroke patients, we found a moderate quality of evidence that MT as an additional therapy improves recovery of arm function after stroke. The quality of evidence regarding the effects of MT on the recovery of lower limb functions is still low, with only one study reporting effects. In patients with CRPS and PLP, the quality of evidence is also low." [15] A recent Cochrane Review summarised the effectiveness of mirror therapy for improving motor function, activities of daily living, pain and visuospatial neglect in patients after stroke. 14 studies with a total of 567 participants that compared mirror therapy with other interventions were compared. At the end of treatment, mirror therapy improved movement of the affected limb and the ability to carry out daily activities, it reduced pain after stroke, but only in patients with a complex regional pain syndrome and the beneficial effects on movement were maintained for six months, but not in all study groups[16].

Phantom Limb Pain[edit | edit source]

Mirror therapy, a non-pharmacological and alternative treatment strategy that has been proven successful in managing phantom limb pain (PLP), is a neurorehabilitation technique designed to remodulate cortical mechanisms of pain. With this technique, patients perform movements using the unaffected limb while watching its mirror reflection superimposed over the (unseen) affected limb, thus creating a visual illusion (and therefore positive feedback to the motor cortex) of movement of the affected limb. The visual illusion of movement of the affected limb generates positive feedback to the motor cortex, which might in turn interrupt the pain cycle[17].

Considering the importance of PLP and its management, as well as the potential effectiveness of mirror therapy as an easy-to-use and low-cost adjuvant therapeutic technique, it seems that this modality can be widely used to treat PLP, Although future research including randomized controlled trials to evaluate the efficacy of mirror therapy in PLP is warranted. [18]

CRPS

[edit | edit source]

Working with patients with different complex regional pain syndromes can be challenging. Pharmacological therapies are often associated with variety of side effects. Mind-body modalities are thought to play a role; however, the lack of clear consensus and large body of clinical experience makes it hard to provide good evidence-based recommendation to most of our chronic pain patients.

Current evidence supports the use of Mirror Box Therapy. [19]

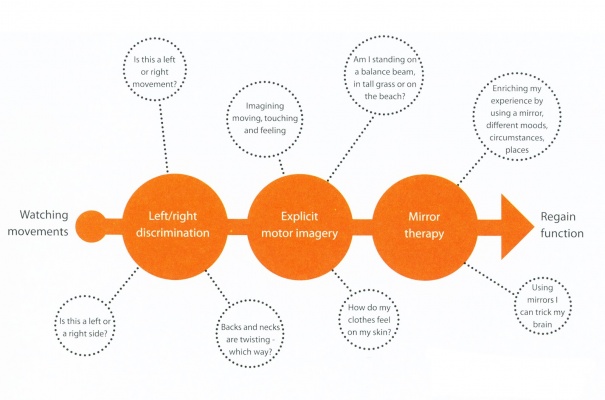

Graded Motor Imagery[edit | edit source]

Graded Motor Imagery (GMI) is a rehabilitation process used to treat pain and movement problems related to altered nervous systems by exercising the brain in measured and monitored steps which increase in difficulty as progress is made.

GMI involves 3 steps as follows:

- Left/right discrimination training

- Motor imagery exercises

- Mirror therapy

These techniques are delivered sequentially but require a flexible approach from the patient and clinician to move forwards, backwards and sideways in the treatment process to suit the individual. [20]

Read 4 Credit[edit | edit source]

|

Would you like to earn certification to prove your knowledge on this topic? All you need to do is pass the quiz relating to this page in the Physiopedia member area. |

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed) [edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1lkZ0SIS2BVBgrFPxtGqkeJvHnfp2QoBXo9jjxd1TNjvx3tgmo|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ Ramachandran, V. S.; Hirstein, W. (1998), "The perception of phantom limbs: The D.O. Hebb lecture", Brain 9 (121): 1603–1630

- ↑ Ramachandran, V. S.; Blakeslee, S. (1998), Phantoms in the brain: Probing the mysteries of the human mind, William Morrow Company, ISBN 0-688-15247-3

- ↑ Ramachandran, V. S.; Rogers-Ramachandran, D. C. (1996), "Synaesthesia in phantom limbs induced with mirrors", Proceedings of the Royal Society of London (263(1369)): 377–386, doi:10.1098/rspb.1996.0058, PMID 8637922

- ↑ Ramachandran, V. S.; Rogers-Ramachandran, D. C.; Cobb, S. (1995), "Touching the phantom", Nature (377): 489–490

- ↑ Ramachandran, VS; Altschuler, EL; Stone, L; Al-Aboudi, M; Schwartz, E; Siva, N (1999), "Can mirrors alleviate visual hemineglect?", Medical Hypotheses 52 (4): 303–305, doi:10.1054/mehy.1997.0651, PMID 10465667

- ↑ Altschuler, E. L.; Wisdom, S. B.; Stone, L.; Foster, C.; Galasko, D.; Llewellyn, D. M.; Ramachandran, V.S. (1999), "Rehabilitation of hemiparesis after stroke with a mirror.", Lancet (353(9169)): 2035–2036

- ↑ Vittorio Gallese and Alvin Goldman, Mirror neurons and the simulation theory of mind-reading, Trends in Cognitive Sciences – Vol. 2, No. 12, December 1998, 1364-6613/98/$

- ↑ Ashu Bhasin, MV Padma Srivastava, Senthil S Kumaran, Rohit Bhatia, Sujata Mohanty, Neural interface of mirror therapy in chronic stroke patients: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study, 2012, Neurology India, 60, 6, 570-576.

- ↑ Diers, M; Christmann, C; Koeppe, C; Ruf, M; Flor, H (2010), "Mirrored, imagined, and executed movements differentially activate sensorimotor cortex in amputees with and without phantom limb pain", PAIN 149 (2): 296–304, doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.02.020, PMID 20359825

- ↑ Moseley, GL; Gallace, A; Spence, C (2008), "Is mirror therapy all it is cracked up to be? Current evidence and future directions", PAIN 138 (1): 7–10, doi:10.1016/j.pain.2008.06.026, PMID 18621484

- ↑ Ezendam, D.; Bongers, RM.; Jannink, MJ. (2009), "Systematic review of the effectiveness of mirror therapy in upper extremity function", Disability Rehabilitation 20 (May): 1–15

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Rothgangel, AS; Braun, SM; Beurskens, AJ; Seitz, RJ; Wade, DT (2011), "The clinical aspects of mirror therapy in rehabilitation: a systematic review of the literature", International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 34 (March): 1–13, doi:10.1097/MRR.0b013e3283441e98, PMID 21326041

- ↑ Giummarra, Melita; Moseley, Lorimer (2011), "Phantom limb pain and bodily awareness:current concepts and future directions", Current Opinions in Anesthesiology 24: 524–531

- ↑ /Subeyaz,S, Yavuzer,G, Sezer,N, Koseoglu,F, Mirror Therapy Enhances Lower-Extemity Motor Recovery and Motor Functioning After Stroke: A Randomized Controlled Trial, Archives Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Vol 88, May 2007[1]

- ↑ Rothgangel,S, Braun,S, Beurskens,A, Seitz,R, Wade,D, The clinical aspects of mirror therapy in rehabilitation: a systematic review of the literature, Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 34:1-13,2011[2]

- ↑ Thieme H, Mehrholz J, Pohl M, Behrens J, Dohle C. Mirror therapy for improving motor function after stroke. The Cochrane Library, 14 March 2012.

- ↑ Cacchio A, De Blasis E, De Blasis V, Santilli V, Spacca G. Mirror therapy in complex regional pain syndrome type 1 of the upper limb in stroke patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009;23:792–799.

- ↑ Farshad Hasanzadeh Kiabi, MD, Mohammad Reza Habibi, MD,* Aria Soleimani, MD,corresponding author and Amir Emami Zeydi,Mirror Therapy as an Alternative Treatment for Phantom Limb Pain: A Short Literature Review, Korean J Pain. 2013 July; 26(3): 309–311.

- ↑ Lamont K, Chin M, Kogan M., Mirror box therapy: seeing is believing. Explore (NY). 2011 Nov-Dec;7(6):369-72.

- ↑ Bowering KJ, O'Connell NE, Tabor A, Catley MJ, Leake HB, Moseley GL, Stanton TR., The effects of graded motor imagery and its components on chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2013 Jan;14(1):3-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.09.007. Epub 2012 Nov 15.

[[Category:]]