Ankylosing Spondylitis (Axial Spondyloarthritis): Difference between revisions

Rachael Lowe (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Scott Buxton (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

*Bamboo spine<br> | *Bamboo spine<br> | ||

Common non-movement related symptoms include: | |||

*Night sweats | |||

*Iritis | |||

*Ulcerative colitis | |||

== Differential Diagnosis<br> == | == Differential Diagnosis<br> == | ||

Revision as of 10:53, 13 June 2015

Original Editor - Thomas Rodeghero

Top Contributors - Laura Ritchie, Kalyani Yajnanarayan, Admin, Mathieu Henrotte, Vanwymeersch Celine, Jack Rubotham, Nikhil Benhur Abburi, Jacintha McGahan, Kim Jackson, Ajay Upadhyay, Rich Lee, Thomas Rodeghero, Rachael Lowe, Lucinda hampton, Anthony Willey, Lilian Ashraf, Jarapla Srinivas Nayak, Scott Cornish, Scott Buxton, Candace Goh, 127.0.0.1, Anouk Van den Bossche, Jess Bell, Niels Cloet, Evan Thomas, Shaimaa Eldib, Sai Kripa, Sanne Peeten, Evelien De Wolf, Aminat Abolade, WikiSysop, Neil Arun, Joshua Samuel, Vidya Acharya, Michelle Lee, Manisha Shrestha, Eva Devliegher, Tony Lowe, Venugopal Pawar and Els Bernaers

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

| [1] |

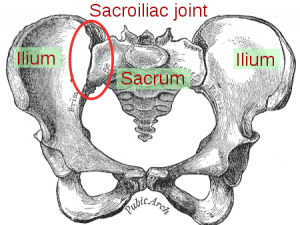

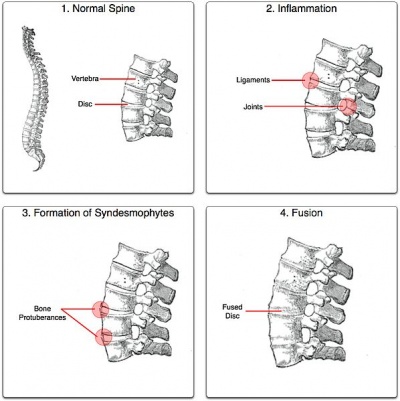

Ankylosing spondylitis (also called Bechterew's disease) is a spondyloarthritis of the spine and pelvis. Affected joints progressively become stiff and sensitive due to a bone formation at the level of the joint capsule and cartilage. Regions most affected by the disease are the axial skeleton and sacroiliac joints. It causes a decreased range of motion and gives the spine an appearance similar to bamboo, hence the alternative name "bamboo spine".

Other joints such as hips, knees, ankles, shoulders and temporomandibular joints may also be affected by the disease but in the majority of cases, the back and neck are the most affected regions. Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is often associated with other chronic inflammatory diseases such as reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, juvenile chronic arthritis, ulcerative colitis, iritis and Crohn’s disease, which can be used as signs for the diagnosis of AS.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

File:Axial skeleton.png Axial Skeleton |

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

The etiology of AS is not fully understood at this time, although a strong genetic link has been determined.[2] In addition, a direct relationship between AS and the major histocompatibility human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27 has also been determined.[3] The exact role of this antigen is unknown but is believed to act as a receptor for an inciting antigen leading to AS.

Ninety percent of patients with AS seem to have a deficit of this antigen but not everyone with this deficit develops the condition. This is why the exact role of the B27 antigen is still to be determined in the cause of AS. [4]

The most supported information known about the pathological process of AS is that it affects the subchondral granulation tissue and creates small lesions, ultimately leading to joint erosion.[5] In the spine this occurs at the junction of the vertebrae and the annular fibres of the intervertebral disc. These lesions in the annulus eventually undergo ossification, leading to a 'fusion' effect of the spinal segments and the similarity in appearance to bamboo.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

AS is predominantly seen in males in a 3:1 ratio and the onset of symptoms generally occurs in late adolescent years to early adulthood. Onset of symptoms past the age of 45 is uncommon.

The clinical presentation is usually an insidious onset of back pain in the sacroiliac (SI) joints and gluteal regions. Morning stiffness lasting greater than 30 minutes is a common subjective complaint, as well as waking up in the second half of the night. Pain is usually exacerbated with rest and relieved with physical activity. Complaints of intermittent breathing difficulties may also be a common complaint because AS may cause a decrease in chest expansion.

Common physical findings include:

- Forward flexed, or stooped, posture

- Decreased spinal segmental mobility

- Tenderness on palpation of the SI regions

- Bamboo spine

Common non-movement related symptoms include:

- Night sweats

- Iritis

- Ulcerative colitis

Differential Diagnosis

[edit | edit source]

Common disorders to consider as differential diagnoses with AS are:

- Fractures and/or dislocation

Differential Diagnosis made easy:

1. Osteoarthritis:

o Presents with mechanical pain typically becoming worse at the end of the day and after activity, with no morning symptoms.

o May occur after lifting or bending.

o The history differentiates mechanical back pain from inflammatory back pain.

2. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH):

o Typically presents with mechanical symptoms.

o Age of onset may help differentiate this condition from AS, as onset tends to be in the 50- to 75-year age group.

3. Psoriatic arthritis:

• Tends to present in the 35- to 45-year age group. No sex bias.

• Sacroiliitis may be unilateral.

• History of psoriasis.

4. Reactive arthritis:

o Patients usually recall a specific infection: for example, a non-gonococcal urethritis or gastroenteritis.

o Dactylitis and skin manifestations occur more frequently than in AS.

o May present with keratoderma blennorrhagica, conjunctivitis, or urethral discharge.

5. Inflammatory bowel-related arthritis:

• History of Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis.

• Peripheral joint involvement common.

• May have evidence of erythema nodosum or pyoderma gangrenosum.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis of AS is commonly made through a combination of thorough subjective and physical examinations, laboratory data and imaging studies. Common laboratory data include the presence of the HLA-B27 antigen, although its presence is not required for a diagnosis of AS. In addition, high C-reactive proteins (CRP) are found in approximately 75% of people with AS.[6] However, this test is discouraged because it is associated with a high rate of false positives due to the fact that high CRP occurs in 10% of the caucasian population.[4]

Standard questionnaires can be used as part of the assessment to sketch the evolution of the disease.[7] Available questionnaires include:

- AMOR criteria

- BASDAI index

- BASFI index

- BAS-G index

The New York criteria for diagnosing AS combines physical findings with radiograph studies. Physical findings include limitations of lumbar spine motion in three planes, pain (or history of pain) at the thoraco-lumbar junction or lumbar spine and a limitation of chest expansion to one inch or less measured at the 4th intercostal space. Radiographic findings are graded on a scale of 0 to 4 where 0 represents normal findings and 4 represents complete ankylosis.[8] A definitive diagnosis is considered with the following combinations.

- Grade 3 or 4 at bilateral SI joints on radiograph with at least one physical finding

- Grade 3 or 4 unilaterally (or Grade 2 bilaterally) with two physical findings

The modified New York (1984) classification criteria

1. Clinical criteria

a) Low back pain and stiffness for at least 3 months, which improves with exercise, but is not relieved by rest

b) Limited lumbar spinal motion in sagittal (sideways) and frontal (forward and backward) planes.

c) Chest expansion decreased relative to normal values corrected for age and sex

2. Radiologic criteria

1. Bilateral sacroiliitis grade 2 to 4

2. Unilateral sacroiliitis grade 3 or 4

3. Definite AS, if one radiologic criterion is associated with at least one clinical criterion

4. Probable AS, if three clinical criteria are present or one radiologic criterion is present without any clinical criterion [9]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Certain quality of life or global rating of change outcome measures may be most appropriate in the physical therapy setting because AS often affects the patient on a more general level. However, since AS affects the spine, outcome measures such as the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) and Neck Disability Index (NDI) may also be appropriate. Laboratory values, such as the CRP, are used to monitor the effectiveness of medication treatments.

Examination[edit | edit source]

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and intra-articular coriticosteroids are accepted, often-used treatments for ankylosing spondylitis.[13] Indomethacin, naproxen and diclofenac are among those most frequently used in AS. [14] However, as in other rheumatic diseases, NSAIDs are valuable only to improve the symptoms of spinal inflammation. There is no evidence that long-term treatment affects the radiologic outcome or function. It is widely believed that relief from pain is associated with an improved ability to exercise daily which, over time, supports the maintenance of function and helps to prevent the joints from stiffening.

There are no established disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) for AS as there are for rheumatoid arthritis. The best investigated DMARD for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis is sulfasalazine. In two placebo-controlled studies, efficacy for peripheral arthritis but no clear effects on axial symptoms was reported. [15][16] Sulfasalazine is thereby effective for peripheral arthritis in spondyloarthritis but there is no clear option for the axial manifestations. Less information is available about the efficacy of other DMARDs in AS.

Very limited data on steroid treatment for ankylosing spondylitis are available. The overall efficacy is not enormous but there are individual patients who seem to benefit in terms of reduced pain and disease activity. A positive effect on reduced bone mineral density can also be expected.

The efficacy of bisphosphonates in metastatic bone disease is well established. There have been two positive reports from small, open studies in the treatment of AS with pamidronate. Both spinal and peripheral disease were successfully treated by this intravenously applied bisphosphonate, [17][18] which is active against osteoclasts and is occasionally used for the treatment of osteoporosis. [19]

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy is an essential part in the treatment of AS.[20] It aims to alleviate pain, increase spinal mobility and functional capacity, reduce morning stiffness, correct postural deformities, increase mobility and improve the psychosocial status of the patients.

The Global Postural Reeducation method has shown promising short- and long-term results.[21] It includes specific strengthening and flexibility exercises in which the shortened muscle chains are stretched. A global and functional approach is more efficient than analytic exercises in AS patients.[22] Muscle chains are constituted by gravitational muscles (erector spine muscles, piriformis muscle, scalene muscles, suboccipital muscles) which work synergistically with each other. The analytic stretching of any individual gravitational muscle would be inefficient if not associated with a stretching of the whole muscle chain.

The GPR method results in greater improvement with a group physical therapy program than with home exercises. This can be explained by the mutual encouragement, reciprocal motivation, and exchange of experience in group therapy.

Since a decrease in chest expansion is secondary to ankylosis in AS, there is also pulmonary involvement. This may even further decrease the low psychological status and quality of life in patients with AS.[23] By performing the following exercises, the chest expansion can increase, leading to better functional capacity.[24]

- twice the normal rate of inspiration through the nose and expiration through the mouth

- normal expiration through nose and normal expiration through mouth

- respiration through the chest and abdomen

- deep breathing and then expiration through the mouth slowly

- resistance exercises for inspiratory pulmonary muscles

Manual mobilization improves chest expansion, posture and spinal mobility.[25] Both active angular and passive mobility exercises can be used in the physiological directions of the joints in the spinal column and the chest wall in flexion, extension, lateral flexion and rotation and in different starting positions (lying face down, sideways, on the back and in a sitting position). Passive mobility exercises consist of general, angular movements and specific translatory movements.

In addition to conventional exercises (flexibility exercises for cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine and major muscle groups) and respiratory exercises (pursed-lip breathing, expiratory abdomen augmentation, and synchronization of thoracic and abdominal movement), aerobic exercises such as swimming and walking are recommended. Research has shown a significant increase in chest expansion following swimming programs and a significant increase in PvO2 and Six Minute Walk Test distances in patients practicing swimming and/or walking aerobic exercises. [23] Aerobic exercises lead to a bigger chest expansion and therefore a better functional capacity. It also decreases the chance of respiratory failure.

Spa therapy has shown significant positive short- and long-term effects on pain, stiffness, well-being and functioning of patients with AS.[26] However, this treatment is very expensive and since the optimal length of therapy is four weeks, this is unfeasible for many people, especially those who are in the workforce or have families at home.

Resources [edit | edit source]

Presentations[edit | edit source]

|

Ankylosing Spondylitis

This presentation, created by Kyle Martin, Robby Martin, Haley Metzner, and Stacey Potter; Texas State DPT Class. |

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1p9j2Ia0knT9gkJRpfmqWR4Pk3y8v7JBAfSH2f31CW8M6bzsAK|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Dr. G. Vilke.SPONDYLITISdotORG. Areas of Inflammation in AS. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2s8eueQ4-eM[last accessed 24/08/12]

- ↑ van der Linden S, van der Heijde D. Clinical aspects, outcome assessment, and management of ankylosing spondylitis and postenteric reactive arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000;12(4):263-268.

- ↑ Alvarez I, López de Castro JA. HLA-B27 and immunogenetics of spondyloarthropathies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000;12(4):248-253

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Maksymowych W. Ankylosing spondylitis. Not just another pain in the back. Can Fam Physician. 2004;50:257-262.

- ↑ McGonagle D, Emery P. Enthesitis, osteitis, microbes, biomechanics, and immune reactivity in ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(10):2302-2304.

- ↑ Dougados M, Gueguen A, Nakache JP, Velicitat P, Zeidler H, Veys E, et al. Clinical relevance of C-reactive protein in axial involvement of ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(4):971-974.

- ↑ Karatepe AG, Akkoc Y, Akar S, Kirazli Y, Akkoc N. The Turkish versions of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis and Dougados Functional Indices: reliability and validity. Rheumatol Int. 2005;25(8):612–618.

- ↑ van der Heijde D, Spoorenberg A. Plain radiographs as an outcome measure in ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(4):985-987.

- ↑ Sjef Van Der Linden, Hans A. Valkenburg Evaluation of Diagnostic Criteria for Ankylosing Spondylitis. Arthritis &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; RheumatismfckLRVolume 27, Issue 4, pages 361–368, April 1984

- ↑ bjchealthAU. Modified Schober's Test. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B9RaFB5BwrQ [last accessed 01/12/12]

- ↑ bjchealthAU. Lumbar Side Flexion Test. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c-IeFZkPEoE [last accessed 01/12/12]

- ↑ bjchealthAU. Chest Expansion Test. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SumtVr5c1Qg [last accessed 01/12/12]

- ↑ Amor B, Dougados M, Mijiyawa M. Criteria for the classification of spondylarthropathies. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic 1990;57(2):85-89.

- ↑ Calin A, Elswood J. A prospective nationwide cross-sectional study of NSAID usage in 1331 patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 1990;17(6):801-803.

- ↑ Dougados M, van der Linden S, Leirisalo-Repo M, Huitfeldt B, Juhlin R, Veys E, et al. Sulfasalazine in the treatment of spondylarthropathy. A randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(5):618-627.

- ↑ Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Abdellatif M. Comparison of sulfasalazine and placebo for the treatment of axial and peripheral articular manifestations of the seronegative spondylarthropathies: a Department of Veterans Affairs cooperative study. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(11):2325-2329

- ↑ Maksymowych WP, Jhangri GS, Leclercq S, Skeith K, Yan A, Russell AS. An open study of pamidronate in the treatment of refractory ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(4):714-717.

- ↑ Maksymowych WP, Lambert R, Jhangri GS, Leclercq S, Chiu P, Wong B, Aaron S, Russell AS. Clinical and radiological amelioration of refractory peripheral spondyloarthritis by pulse intravenous pamidronate therapy. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(1):144-155.

- ↑ Braun J, Sieper J. Therapy of ankylosing spondylitis and other spondyloarthritides: established medical treatment, anti-TNF-α therapy and other novel approaches. Arthritis Res. 2002;4(5):307-21.

- ↑ Dagfinrud H, Kvien TK, Hagen KB. The Cochrane review of physiotherapy interventions for ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(10):1899-1906.

- ↑ What is Global Postural Re-education?fckLREmiliano Grossi, Centre of Global Postural Re-education Fisio-Clinic – Rome, Italy

- ↑ Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Alonso-Blanco C, Alguacil-Diego IM, Miangolarra-Page JC. One-year follow-up of two exercise interventions for the management of patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006; 85(7):559-567.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Karapolat H, Eyigor S, Zoghi N, Akkoc Y, Kirazli Y, Keser G. Are swimming or aerobic exercise better than conventional exercise in ankylosing spondylitis patients? A randomized controlled study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2009;45(4):449-457.

- ↑ Ince G, Sarpel T, Durgun B, Erdogan S. Effects of a multimodal exercise program for people with ankylosing spondylitis. Phys Ther. 2006;86(7):924-935.

- ↑ Widberg K, Karimi H, Hafström I. Self- and manual mobilization improves spine mobility in men with ankylosing spondylitis--a randomized study. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(7):599-608.

- ↑ Scholten-Peeters GGM, Dijkstra PU, Vaes P, Verhagen AP. Bohn Stafleu Van Longhum. Jaarboek Kinesitherapie. 2004.