Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Original Editors - Alli Christian from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project. Top Contributors - Alli Christian, Elaine Lonnemann, Admin, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Rachael Lowe, Lotte Vonck, Khloud Shreif, 127.0.0.1, Laura Ritchie, Wendy Walker and WikiSysop - Elaine Lonnemann

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an inflammatory connective tissue disease with variable manifestations.

- SLE may affect many organ systems with immune complexes and a large array of autoantibodies, particularly antinuclear antibodies (ANAs).

- Although abnormalities in almost every aspect of the immune system have been found, the key defect is thought to result from a loss of self-tolerance to autoantigens.[1]

- It is a disease characterized by relapses, flares, and remissions.

- Common manifestations, in addition to the malar rash, include cutaneous photosensitivity, nephropathy, serositis, and polyarthritis.

- The overall outcome of the disease is highly variable with extremes ranging from permanent remission to death[2].[3] [4]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

- There is a strong female predilection in adults, with women affected 9-13 times more than males. In children, this ratio is reversed, and males are affected two to three times more often.

- Can affect any age group - the peak age at onset around the 2nd to 4th decades, with 65% of patients presenting between the ages of 16 and 65 years (i.e. during childbearing years).

- Disease is more common in childbearing age in women however it has been well reported in the pediatric and elderly population. SLE is more severe in children while in the elderly, it tends to be more insidious onset and has more pulmonary involvement and serositis and less Raynaud's, malar rash, nephritis, and neuropsychiatric complications[5]

- Studies have indicated that although rare, lupus in men tends to be more severe.

- Prevalence varies according to ethnicity with ratios as high as 1:500 to 1:1000 in Afro-Caribbeans and indigenous Australians, down to 1:2000 in Caucasians.[1]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The cause of lupus erythematosus is not known.

- A familial association has been noted that suggests a genetic predisposition, but a genetic link has not been identified. Approximately 8% of patients with SLE have at least one first-degree family member (parent, sibling, child) with the disease.

- Environmental factors - Ultraviolet light (increased keratinocyte apoptosis), infection (via molecular mimicry and bacterial CpG motifs), smoking (odds ratio (OR): 1.56 in current smokers, 1.23 in ex-smokers), environmental pollutants (silica) and intestinal dysbiosis (ie digestive disturbances, frequent gas or bloating, feel bloated on most days of the week, abdominal cramping, diarrhea, and constipation) are all known risk factors for SLE.

- Hormonal abnormality and ultraviolet radiation are considered possible risk factors for the development of SLE[1].

- Some drugs have been implicated as initiating the onset of lupus-like symptoms and aggravating existing disease; they include hydralazine hydrochloride, procainamide hydrochloride, penicillin, isonicotinic acid hydrazide, chlorpromazine, phenytoin, and quinidine.

- Possible childhood risk factors include low birth weight, preterm birth, and exposure to farming pesticides[6].

Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

SLE can affect multiple components of the immune system, including the

- Complement system (ie a part of the immune system that enhances the ability of antibodies and phagocytic cells to clear microbes and damaged cells from an organism, promote inflammation, and attack the pathogen's cell membrane),

- T-suppressor cells

- Cytokine production.

Emerging evidence has demonstrated a key player in the generation of autoantigens in SLE is the increase in generation (i.e. increased apoptosis) and/or decrease in clearance of apoptotic cell materials (i.e., decreased phagocytosis).

Results in generation of autoantibodies, which may circulate for many years prior to the development of overt clinical SLE. The disease tends to have a relapsing and remitting course.[1]

SLE has a myriad of clinical features:

- CNS manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (CNS lupus): neuropsychiatric events can occur in ~45% (range 14-75%) of cases

- gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: there may be GI involvement in ~20% of cases

- musculoskeletal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus

- renal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus

- thoracic manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus.[1][3]

Clinical Presentation [edit | edit source]

SLE can affect many organs of the body, but it rarely affects them all. The following list includes common signs and symptoms of SLE in order of the most to least prevalent. All of the below symptoms might not be present at the initial diagnosis of SLE, but as the disease progresses more of a person’s organ systems become involved.[7] The most common symptoms associated with SLE are:

- Constitutional symptoms (fever, malaise, fatigue, weight loss): most commonly fatigue and a low-grade fever

- Achy joints (arthralgia)

- Arthritis (inflamed joints)

- Skin rashes

- Pulmonary involvement (symptoms include: chest pain, difficulty breathing, and cough)

- Anemia

- Kidney involvement (lupus nephritis)

- Sensitivity to the sun or light (photosensitivity)

- Hair loss

- Raynaud’s phenomenon

- CNS involvement (seizures, headaches, peripheral neuropathy, cranial neuropathy, cerebrovascular accidents, organic brain syndrome, psychosis)

- Mouth, nose, or vaginal ulcers”[3]

- The most common signs and symptoms of SLE in children and adolescents are: "fever, fatigue, weight loss, arthritis, rash, and renal disease."[8]

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

There are many visceral systems can be affected from SLE, but the extent of the body's involvement differs from person to person. Some people diagnosed with SLE have only few visceral systems involved, while others have numerous systems that have been affected by the disease.

Musculoskeletal System:[edit | edit source]

- Arthritis- typically affects hand, wrists, and knees

- Arthralgia

- Tenosynovitis

- Tendon ruptures

- Swan-neck deformity

- Ulnar drift

Cardiopulmonary/Cardiovascular System:[edit | edit source]

- Pleuritis

- Pericarditis

- Dyspnea

- Hypertension

- Myocarditis

- Endocarditis

- Tachycarditis

- Pneumonitis

- Vasculitis

- Small Vessels Purpura

- Large Vessels Papular Lesions

- Arterial Thrombosis

Central Nervous System:[edit | edit source]

- Emotional instability

- Psychosis

- Seizures

- Cerebrovascular accidents

- Cranial neuropathy

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Organic brain syndrome

Renal System:[edit | edit source]

- Glomerulonephritis -inflammatory disease of the kidneys

- Hematuria

- Proteinuria

- Kidney failure[3]

Cutaneous System:[edit | edit source]

- Calcinosis

- Cutaneous vasculitis

- Hair loss

- Raynaud's phenomenon

- Mucosal ulcers

- Petechiae

Blood Disorders:[edit | edit source]

- Anemia

- Thrombocytopenia

- Leukopenia

- Neutropenia

- Thrombosis

Gastrointestinal System:[edit | edit source]

- Ulcers--Throat & Mouth

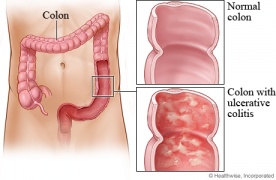

- Ulcerative colitis/Crohn's disease

- Peritonitis

- Ascites

- Pancreatitis

- Peptic ulcers

- Autoimmune Hepatitis [9]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

- About 30% of people diagnosed with SLE are also diagnosed with fibromyalgia.[4]

- Atherosclerosis[10] [11]

- Lupus Nephritis- leads to End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD)

- Anemia[12]

- Some types of cancers (especially non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and lung cancer) [11][13] [14]

- Infections

- Hypertension

- Dyslipidemia

- Diabetes Mellitus

- Osteoporosis

- Avascular Necrosis [11]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Because of the many different symptoms and manifestations of SLE early detection can often be difficult. According to the American Rheumatism Association, a patient must exhibit at least 4 of the following criteria concurrently or successively to be diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus.

- Abnormal titer of antinuclear antibodies (ANAs)

- Butterfly (malar) rash

- Discoid rash

- Hemolytic anemia, leukopenia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia

- Neurologic disorder: seizures or psychosis

- Non-erosive arthritis of two or more peripheral joints characterized by tenderness, swelling, or effusion

- Oral or nasopharyngeal ulcerations

- Photosensitivity

- Pleuritis or pericarditis

- Positive lupus erythematosus cell preparations, anti DNA, or anti-splice sosomal test or chronic false-positive serologic test for syphilis<span id="fck_dom_range_temp_1269546309419_582" />

- Renal disorder: profuse proteinuria (>0.5 grams/day) or excessive cellular casts in urine."[3]

Although laboratory tests along cannot diagnose SLE the following tests may show abnormal results if SLE is suspected:

- Complete Blood Count: This blood test reveals a patient's total number of red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, and hemoglobin. Low white blood cell or platelet counts can be indicative of SLE, whereas low red blood cell counts can be indicate of anemia which commonly occurs in conjunction with SLE.

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate: An elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate can reveal a systemic problem. This test is not specific to SLE, but a postitive test could reveal that the patient could potentially have SLE.

- Kidney and Liver Tests: These tests are completed to determine if a patient's kidneys and liver are functioning properly since SLE can affect these systemic organs.

- Urinalysis: This test is performed to determine if there are proteins or red blood cells present in a patient's urine. If so, this could indicate that the kidneys are damaged, potentially from SLE.

- ANA test: A positive test reveals that a patient could potentially have SLE, but other infections and diseases can cause this test to be positive as well. If positive, further testing is necessary to determine if the positive results occurred due to SLE.

- Chest X-ray: This test is performed to determine if there is inflammation present in the patient's lungs or excessive fluid surrounding his/her heart.

- Syphilis Test: A false-positive syphilis test can reveal that a patient has anti-phospholipids present, and this false-positive test result is indicative that the patient could have SLE.[13]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

The medical management for SLE is primarily drug therapy and is based upon the patients symptoms and systemic involvement. The most widely used medications are:

- Analgesics[1]: These medications are used to control the pain associated with arthralgia, arthritis, and ulcers that are caused by SLE.[15]

- Non-Steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDS): These medications help to decrease tissue inflammation, and therefore decrease the patient’s joint and muscle pain.

- Anti-malarials: These medications are used to treat a patient's arthritic, musculocutaneous, and renal symptoms associated with SLE.

- Chloroquine (Aralen)[3][15]

- Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil)[15] - Corticosteroids[2]: These drugs are only prescribed to patients with severe SLE who experience signs and symptoms that are not improving with any other drug therapy. Corticosteroids can give the patient relief from constitutional symptoms, arthritis, and cutaneous problems caused from SLE.

- Immunosuppressant Agents: These drugs are used to decrease inflammation, treat lupus nephritis, and suppress the patient's immune system.

- Azathioprine (Imuran)

- Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan)[3][15] - Topical medications

In addition to drug therapy, prevention is also very important when dealing with SLE. For patients with photosensitivities, flare-ups can be reduced if patients are cautious about the amount of sunlight or UV light that they are exposed to. Patients with SLE are also encouraged to lead a healthy lifestyle that includes: smoking cessation, controlling alcohol consumption, weight management, and regular exercise.[3][11] Patients with SLE are also encouraged to participate in support groups, ensure they are taking the correct dosages and amounts of medications, and ensure they visit medical professionals regularly.[3] There are also other therapies that claim to have a positive effect on symptoms, such as:

- Hormonal Intervention

- Immunosupressant Therapy

- IV Gamma Globulin

- Apheresis

- Stem-Cell Transplantation

- Biological Therapy[16]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Exercise is beneficial for patients with SLE because it decreases their muscle weakness while simultaneously increases their muscle endurance. Physical therapists can play an important role for patients with SLE during and between exacerbations. The patient's need for physical therapy will vary greatly depending on the systems involved.

- Education: It is essential for patients with skin lesions to have appropriate education on the best way to care for their skin and to ensure they do not experience additional skin breakdown.

- Aerobic Exercise: One of the most common impairments that patients with SLE experience is generalized fatigue that can limit their activities throughout the day.[3] In a study by Tench et al., it was determined that graded aerobic exercise programs are more successful than relaxation techniques in decreasing the fatigue levels of patients with SLE. Aerobic activity caused many of the participants with SLE to feel "much better" or "very much better" at the conclusion of the study. The aerobic exercise program consisted of 30-50 minutes of aerobic activity (walking/swimming/cycling) with a heart rate corresponding to 60% of the patient's peak oxygen consumption.[17] Another study, completed by Ramsey- Goldman et al., concluded that both aerobic exercise and range of motion/muscle strengthening exercises can increase the energy level, cardiovascular fitness, functional status, and muscle strength in patients with SLE. In this study, the patients completed aerobic exercise for 20-30 minutes at 70-80% of their maximum heart rate. The patients who completed range of motion and muscle strengthening activities met 3 times a week for 50 minutes sessions.[18]

- Energy Conservation: Physical therapists can educate patients on appropriate energy conservation techniques and the best ways to protect joints that are susceptible to damage.

- Additionally, physical therapists and patients with SLE should be aware of signs and symptoms that suggest a progression of SLE including those associated with avascular necrosis, kidney involvement, and neurological involvement.[3]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Due to the vast differences in systems and parts of the body involved SLE can often be mistaken for another condition and vice-versa. ANA Profiling is a common procedure to confirm or negate a diagnosis of SLE.

| > 4 Present 96% Sensitive; 96% Specific[19] |

|

ANA Profile[edit | edit source]

Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are a group of autoantibodies produced by a person's immune system when the body is unable to distinguish between "self" and "nonself." The ANA Profile Test detects these autoantibodies in the blood. ANA cause a reaction with the body's own healthy cells causing signs and symptoms associated with SLE and other autoimune conditions. (SLE) are almost always positive for ANA, but the test alone is not enough to confirm diagnosis of SLE, other SLE symptoms must be present. If the ANA profile test is negative a diagnosis of SLE is unlikely[20] [21] The test has a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 57%[22]. Other conditions that have similar symptoms to SLE are:

- Fibromyalgia

- Undifferentiated Connective Tissue Disease

- Auto-immune Rheumatic Disease

- Viral Infections-Epstein-Barr, Cytomegalovirus

- Bacterial Infections

- HIV

- TB

- Malignancies

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Vasculitis [8]

- Multiple Sclerosis [23]

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Radiopedia SLE Available from:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/systemic-lupus-erythematosus (last accessed 5.6.2020)

- ↑ Medscape SLE Available from:https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/305578-overview (last accessed 5.6.2020)

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd edition. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier, 2009. (Level of evidence 5)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Goodman CC and Synder TK. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral. 4th edition. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier, 2007.

- ↑ Julkunen H. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Epidemiology. 2018 Sep 3.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535405/ (last accessed 5.6.2020)

- ↑ Nursing central SLE Available from:https://nursing.unboundmedicine.com/nursingcentral/view/Diseases-and-Disorders/73651/all/Lupus_Erythematosus (last accessed 5.6.2020)

- ↑ "Handout on Health: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus". www.niams.nih.gov. June 2016.(Accessed 28 April 2019).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Tucker LB. Making the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus in children and adolescents. Lupus; 16: 546-549. 2007.

- ↑ Lupus Foundation of America. How lupus affects the body page. Website updated: 2010. Website accessed: February 17, 2010.

- ↑ Becker-Merok A, Nossent JC. Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of vascular damamge in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus; 18: 508-515. 2009.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Bertsias G, Gordon C, Boumpas DT. Clinical trials in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): lessons from the past as we proceed to the future- the EULAR recommendations for the management of SLE and the use of end-points in clinical trials. Lupus; 17: 437-442. 2008.

- ↑ Wingard R. Increased risk of anemia in dialysis patients with comorbid diseases. Nephrology Nursing Journal; 31 (2): 211-214. 2004.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Medical Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Mayo Clinic: Lupus Page. www.mayoclinic.com. Updated October 20, 2009. Accessed February 17, 2010.

- ↑ Bernatsky S, Boivin JF, Joseph L, et al. An international cohort study of cancer in systemic lupus erythematosus.Arthritis & Rheumatism 2005;52(5):1481–90.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Laranzo D. Elderly-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Drugs and Aging; 24 (9):701-715. 2007.

- ↑ Solsky M, Wallace D. New therapies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Best Practice & Res Clin Rheum: 2002; 16; 293-312

- ↑ Tench CM, McCarthy J, McCurdie I, White PD, D'Cruz DP. Fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized control trial of exercise. Rheumatology; 42: 1050-1054. 2003. (Level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ Ramsey-Goldman GR, Schilling EM, Dunlop D, Langman C, Greenland P, Thomas RJ, Chang RW. A pilot study on the effects of exercise in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care and Research; 13(5): 262-269. 2000. (Level of evidence 2B)

- ↑ Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rehumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism 1997; 40: 1725-1734

- ↑ George R, Kurian S, jacob M, Thomas K. Diagnostic evaluation of the lupus band test in discoid and systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Dermatol. 1995 34: 170-173

- ↑ Mehta V, Sarda A, Balachandran C. Lupus band test. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol [serial online] 2010 [cited 2012 Mar 6];76:298-300. Available from: http://www.ijdvl.com/text.asp?2010/76/3/298/62983

- ↑ Solomon DH, Kavanaugh AJ, Schur PH, American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Immunologic Testing Guidelines. Evidence‐based guidelines for the use of immunologic tests: antinuclear antibody testing. Arthritis Care & Research. 2002 Aug 15;47(4):434-44.

- ↑ Bhiglee AI, Bill PL. Case Report: Multiple sclerosis and SLE revisited. Medical Journal of Islamic Academy of Sciences; 12 (3): 79-84. 1999.