Sensory Integration

Original Editor - Nino Chumburidze

Top Contributors - Ewa Jaraczewska, Jess Bell, Lauren Heydenrych and Tarina van der Stockt

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Sensory integration is also known as sensory processing. It refers to the ability of our brain to recognise and respond to signals sent by our sensory system. Our senses include hearing, vision, smell, taste, touch, proprioception, vestibular, and interoception. Sensory integration is important for a child's development and maintenance of social-emotional, motor, cognitive, adaptive, and other skills.[1] When a child has difficulty processing various sensory stimuli, they may be diagnosed with sensory integration dysfunction (SID) / sensory processing disorder (SPD).[2] [3] SPD is a "failure to modulate the effects of incoming sensory inputs."[4] Children can be hypo- or hyper-sensitive to sensory inputs, and their difficulty processing and responding to sensory information can lead to activity limitations, and affect a child's participation in daily activities, school activities, and more. This article discusses sensory integration and SID / SPD and offers recommendations for sensory integration therapy for children with cerebral palsy.

Senses[edit | edit source]

Touch or Tactile Sensation[edit | edit source]

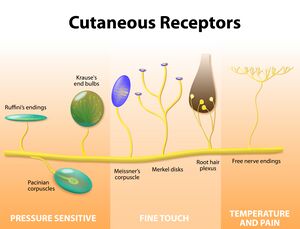

- Information is received from receptor cells in the skin

- Skin (cutaneous) receptors provide information about light touch, pressure, vibration, temperature, and pain. The touch receptors are mechanoreceptors, chemoreceptors and thermoreceptors.

- Mechanoreceptors include the following:

- Hair follicles which affect touch perception

- Pacinian corpuscles allow to discriminate between smooth and rough surfaces

- Meissner corpuscles are sensitive to light touches and allow one to feel a light tickle

- Merkel complexes are activated by the applied pressure and location of objects we interact with

- Ruffini corpuscles are activated by stretching the skin

- C-fiber low threshold mechanoreceptors (LTM) respond to “pleasant” and “effective” mechanical stimuli like gentle stroking and brushing and small changes in skin temperature[5]

- Chemoreceptors respond to chemicals in taste, smell and internal changes. They regulate cardiovascular and respiratory functions.

- Thermoreceptors detect changes in the skin temperature.

- Mechanoreceptors include the following:

Proprioception[edit | edit source]

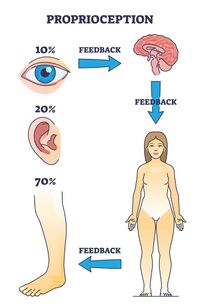

Proprioception (kinaesthesia) helps us to move because of the information arising from skin, muscles, joints, ligaments, and bones.[1] It allows us to perceive the location, movement, and action of the body.[6]

- With the change in position, the tissue surrounding the moving joint becomes deformed[6]

- Muscle spindles are considered to have the major role in kinaesthesia[6]

- The skin receptors provide additional information[6]

- The Golgi tendon organs contribute to proprioception[6]

Vestibular Sense[edit | edit source]

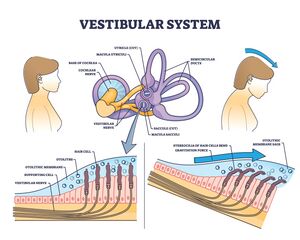

The vestibular system provides information about movement, gravity, and changing head position:[1]

- It informs us that we are moving or stationary.

- It provides information about the direction and speed of our movements.

- It helps to stabilise our eyes when we are moving.

- It informs us if objects around us are moving or stationary.

Hearing[edit | edit source]

- Auditory system processes the sounds of the environment.[1]

- Auditory receptors in the inner ear identify various sound stimuli: intensity, frequency and spectrum.[1]

- Posture control can be influenced by sound frequency.[7]

- It allows us to respond to sound stimuli accordingly, like when the alarm sound acknowledges a safety concern.[1]

Visual[edit | edit source]

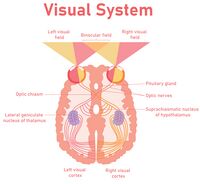

- Helps us see and perceive the environment around us[1]

- Visual system identifies sights and understands what the eyes see[1]

- Visual inspection is important in maintaining body balance as it helps position the body in space[8]

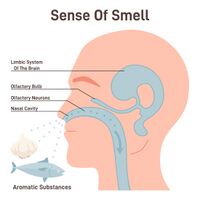

Smell[edit | edit source]

- It allows us to distinguish various odours in the environment.[1]

- It helps us to identify safe or potentially dangerous situations.[1]

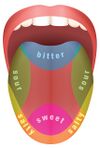

Taste[edit | edit source]

- It distinguishes four tastes: sweet, sour, salty, and bitter.[1]

- It allows us to identify desirable foods that are pleasant to us as well as those that are potentially undesirable, such as a bitter dish.[1]

Interoception[edit | edit source]

Interoception is understanding the body's internal sensations like hunger, thirst, hot, cold, or any other feelings that start with our body. [9]

Sensory Integration[edit | edit source]

Sensory integration "is the potential to develop adequate motor and behavioural reactions to stimulus"--Ayres

The input from the senses is received, organised and interpreted to create a reaction appropriate to the type of stimulation received. This is called sensory processing.

Sensory Integration Dysfunction[edit | edit source]

Sensory Integration Disorder is "difficulty detecting, modulating, interpreting, and/or responding to sensory inputs, which is severe enough to disrupt participation in everyday living activities and routines, as well as learning."[3]

Sensory integration dysfunction is a problem in the ability to ‘‘organise sensory information for use.’’[10]--Ayres

Sensory function is a foundation to motor ability, social skill, and various behaviours. When there is a disruption in modulation, discrimination or integration of sensory input, the cascade effects occur on all levels of sensory processing (motor, social, behavioural). Such a disruption can translate to problems with participation at home, at school, and in the community.[3]

Sensory integration dysfunction may lead to the following deficits:[3]

- initiating or sustaining peer interactions

- developing engaged relationships

- participating in activities of daily living

- regulating arousal behaviours

- language development

In general, the manifestations of sensory integration processing deficits may include the following:[3]

- responses to stimulation more quickly

- responses to stimulation more intensely

- responses to stimulation a longer duration than do typically developing individuals

Examples:[3]

- Extreme responses to stimuli, including noise in a classroom, odours in a restaurant, the touch of clothing, or the movement of playground equipment.

- "Fight, flight or freeze" behavioural responses include aggression, withdrawal, or preoccupation with the expectation of sensory input.

- Severe difficulty forming and maintaining peer relationships

- Extreme efforts to control events in the environment by over-reliance on routines

- Behaviour regulation problems like temper tantrums, outbursts, hitting, kicking, biting, or spitting

- Profound withdrawal from group

- Slow to respond to sensation requiring "more intense stimuli to respond to the demands of the situation"[3]

Sensory Deficits and Cerebral Palsy[edit | edit source]

Children with cerebral palsy often have deficits in one or more sensory systems, including proprioception, tactile sensation, and visual perception.[1] It can affect their functional activities, especially daily activities requiring bilateral upper-extremity use, such as eating, playing, dressing, and showering.[11] Children with cerebral palsy may react to sensory stimuli by:

- Hyper-responsiveness to tactile input:[1]

- Do not like to be touched

- Avoidance of activities that involve getting messy,

- Resistance to light touches

- Avoidance of certain types of clothing

- Hypo-responsiveness to tactile input:[1]

- Lacking the ability to localise touch or response when touched

- Placing items in the mouth

- Preference for activities or situations involving brushing hair, touching or hugging

- Failure to recognise when hands or face are messy

- Enjoyment of activities involving vibration

- Hypo-responsiveness to proprioceptive input:[1]

- Biting or chewing on non-food objects

- Engaging in pinching or hitting others or oneself

- Difficulty in changing body posture to match activity demands

- Expressing low, high, or variable muscle tone impacting the processing of proprioceptive information

- Hyper-responsiveness to proprioceptive input:[1]

- Crying in weight-bearing positions or when joints are moved

- Choosing not to move or engage in activities

- Hyper-responsiveness to vestibular input:[1]

- Overreacting when moved into space

- Becoming fearful of bouncing or swinging

- Disliking sudden or quick movements

- Hypo-responsiveness to vestibular input:[1]

- Enjoying being moved and rocked passively

- Seeking opportunities to fall without regard to safety

- Liking excessive spinning, swinging, and active movements

Sensory Integration Therapy[edit | edit source]

Before incorporating SIT, it is important to understand that there is limited evidence based on SIT, "with few positive outcomes and some null or negative outcomes".[3] SIT includes targeting seven sensations: auditory, visual, gustatory (taste), olfactory (smell), somatosensory (proprioception and touch), vestibular, and interoceptive (the sense involved in the detection of internal regulation, such as heart rate, respiration, hunger, and digestion). [3] It is postulated that sensory integration therapy (SIT) directly improves attentional, emotional, motoric, communication, and/or social difficulties. [12]

Goals:[1]

- To facilitate the child's daily functioning

- To elicit the child's adaptive response in the form of an appropriate reaction to environmental or situational requirements

General Recommendations:[1]

- Establish clear goals.

- Ensure physical safety for the child.

- Prepare the child before starting the activity (safety, posture, muscle tone).

- Promote sensory-enriched activities.

- Collaborate with the child on activity choice and maximise the child's success.

- Guide self-organisation and support optimal arousal.

- Build a therapeutic alliance through positive and supportive relationships.

- Provide the "just-right" challenge.

- Determine the activity's intensity and duration.

- Promote positive experiences and respect children's preferences.

- Integrate into daily routine.

- Incorporate every movement into play.

Environment and Equipment[edit | edit source]

Every environment where the child resides is appropriate for SIT, including schools, homes, yards, and playgrounds. However, the sensory room tends to be utilised for the treatment the most frequently. Ensuring physical safety for the child is very important. One must carefully observe the child's reactions and pay attention to the signs of the child becoming overwhelmed. When it occurs, proactive change of the situation and prompt action in response is necessary. [1]

Equipment for the multi-sensory room should include materials to address the seven senses. Examples include the following:

- Tactile: sand, foam, and various textures.[1]

- Proprioceptive: ball pool, therapy ball, heavy blanket.[1]

- Vestibular: platform swing, bolster swing, net swing, tilt board, trampoline, ramp. [13]

- Hearing: water (fountains, faucets, waves, and waterfalls), music(radio, instruments, chimes), instruments (drums, piano, guitar, keyboards and tambourines). [14]

- Visual: neon, patterned and florescent papers, coloured, strung, flashing, holiday and strobe lights, wind socks, wind-up toys, activity boxes and age-appropriate mobiles. [14]

- Smell: air fresheners(lavender, pot pouri and sachets), candles, lotions, powders, perfumes, flowers, plants, breads, cookies, stews, bacon, onions.[14]

- Taste: fruits, milk-based items, hot and cold items, candies, cheese. [14]

Activities[edit | edit source]

The following activities offer examples of using sensory integration elements to treat sensory deficits.

Tactile Activities[edit | edit source]

- Playing with different brushes, drawing with soap crayons or chalk on the body, and erasing with various textures. [1]

- Engage in different play activities with Play-Doh, like hiding small objects in it or creating a tactile bin for finger exploration. [1]

- Exploring kitchen time activities, such as mixing, tasting, smelling, and washing vegetables. [1]

- Preparing a tactile bag using a zipper bag filled with conditioner cream and food colours and hidden inside small beans or toys[1]

- Creating sensory balloons with materials like balloons filled up with cereals, flowers, and sand. [1]

- Making a tactile board using a piece of wood, tissue, and different materials.[1]

Proprioceptive Activities[edit | edit source]

- Engaging in playground activities. [1]

- Participating in gross motor activities. [1]

- Encouraging imitations of various movements. [1]

- Weight-bearing activities, such as crawling and push-ups.[1]

- Resistance activities like pushing and pulling.[1]

Vestibular Stimulation Activities[edit | edit source]

- Spinning, rocking, climbing, sliding, riding toys, walking, running. [1]

- Standing on one foot and standing on one foot with eyes closed. [14]

- Throwing a ball. [14]

- Shaking the head. [14]

- Bouncing on bed, ball or parent’s knees. [14]

- Swinging in a blanket, in swings, or on a rope. [14]

- Turning head left and right at a rapid pace. [14]

Resources[edit | edit source]

- What is Sensory Integration?

- Warutkar VB, Krishna Kovela R. Review of Sensory Integration Therapy for Children With Cerebral Palsy. Cureus. 2022 Oct 26;14(10):e30714.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 1.31 1.32 1.33 1.34 1.35 Chumburidze N. Sensory Integration. Plus Course 2024

- ↑ Miller LJ, Nielsen DM, Schoen SA, Brett-Green BA. Perspectives on sensory processing disorder: a call for translational research. Front Integr Neurosci. 2009 Sep 30;3:22.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Camarata S, Miller LJ, Wallace MT. Evaluating Sensory Integration/Sensory Processing Treatment: Issues and Analysis. Front Integr Neurosci. 2020 Nov 26;14:556660.

- ↑ Barakat MKA, Elmeniawy GH, Abdelazeim FH. Sensory systems processing in children with spastic cerebral palsy: a pilot study. Bull Fac Phys Ther. 2021; 26 (27).

- ↑ Huzard D, Martin M, Maingret F, Chemin J, Jeanneteau F, Mery PF, Fossat P, Bourinet E, François A. The impact of C-tactile low-threshold mechanoreceptors on affective touch and social interactions in mice. Sci Adv. 2022 Jul;8(26):eabo7566.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Proske U, Gandevia SC. The proprioceptive senses: their roles in signalling body shape, body position and movement, and muscle force. Physiol Rev. 2012 Oct;92(4):1651-97.

- ↑ Siedlecka B, Sobera M, Sikora A, Drzewowska I. The influence of sounds on posture control. Acta of Bioengineering and Biomechanics 2015;17(3):95-102.

- ↑ Pankanin E. Visual control is important in maintaining the body's balance. Journal of Education, Health and Sport. 2018;8(8):381-387.

- ↑ Sensory. Available from https://pathways.org/topics-of-development/sensory/ [last access 13.02.2024]

- ↑ AYRES AJ. THE DEVELOPMENT OF PERCEPTUAL-MOTOR ABILITIES: A THEORETICAL BASIS FOR TREATMENT OF DYSFUNCTION. Am J Occup Ther. 1963 Nov-Dec;17:221-5.

- ↑ Erkek S, Çekmece Ç. Investigation of the Relationship between Sensory-Processing Skills and Motor Functions in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Children. 2023; 10(11):1723.

- ↑ Miller LJ, Fuller DA, Roetenberg J. (2014). Sensational Kids: Hope and Help for Children With Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD). New York, NY: Penguin.

- ↑ Rassafiani M, Akbarfaimi N, Hosseini SA, Shahshahani S, Karimlou M, Tabatabai Ghomsheh F. The Effect of the combination of active vestibular interventions and occupational therapy on Balance in Children with Bilateral Spastic Cerebral Palsy: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Iran J Child Neurol. 2020 Fall;14(4):29-42.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 14.8 14.9 Sensory Integration. Available from https://www.cerebralpalsy.org/about-cerebral-palsy/treatment/therapy/sensory-integration-therapy [last access 13.02.2024]