Lumbar Instability: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

</div> <div class="editorbox"> | </div> <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editors ''' - [[User:Anke Jughters|Anke Jughters]] | '''Original Editors ''' - [[User:Anke Jughters|Anke Jughters]], <topcontributors>Liese Bosmans</topcontributors> | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} <br><br><br> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Search strategy == | == Search strategy == | ||

• Databases searched: Physiopedia , Pedro , Pubmed<br>• Keywords searched : ‘Lumbar Instability’, ‘spine instability’, ‘exercises lumbar instability’ ,<br>‘Lumbar spine instability‘ , ‘‘Lumbar instability treatment’, ‘medical management lumbar<br>instability’, ‘low back school’ , ‘Lumbar instability physical examination’, ‘segmental instability’, ‘<br>physical mangement lumbar instability’<br> | • Databases searched: Physiopedia , Pedro , Pubmed<br>• Keywords searched : ‘Lumbar Instability’, ‘spine instability’, ‘exercises lumbar instability’ ,<br>‘Lumbar spine instability‘ , ‘‘Lumbar instability treatment’, ‘medical management lumbar<br>instability’, ‘low back school’ , ‘Lumbar instability physical examination’, ‘segmental instability’, ‘<br>physical mangement lumbar instability’<br> | ||

== Definition/Description == | == Definition/Description == | ||

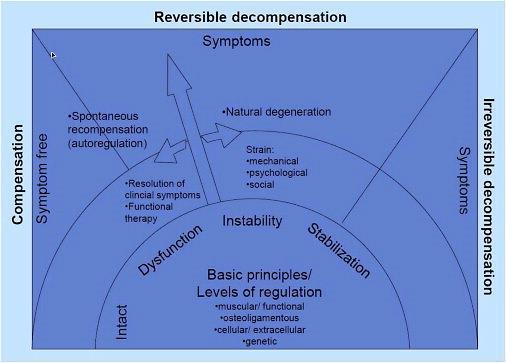

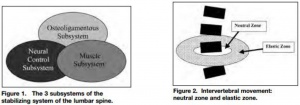

<u></u>Lumbar instability is an important cause of low back pain and can be associated with substantial disability.<ref name="82">T. Barza, M. Melloh etal. A conceptual model of compensation/decompensation in lumbar segmental instability. Medical Hypotheses. Volume 83, Issue 3, September 2014, Pages 312–316 Level of evidence: 4</ref> The word ‘instability’ is still poorly defined. But it is most widely believed that the loss of a normal pattern of spinal motion causes pain and/or neurologic dysfunction. The American Academy of Orthopaedics Surgeons <ref name="4">American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeon : A glossary on spinal terminology. Chicage 1985</ref> state: ‘Segmental instability is an abnormal response to applied loads, characterized by motion in motion segments beyond normal constraints.’ Panjabi published a spinal stabilization system represented by 3 subsystems:<br> the passive, the active and the neural control subsystem.<ref name="2">Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part I. Function, dysfunction, adaptation, and enhancement. J Spinal Dis. 1992;5:383-389. Level of evidence: 4</ref><br> Segmental instability is defined by Panjabi <ref name="3">Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part II. Neutral zone and instability hypothesis. J Spinal Dis. 1992;5:390-397. Level of evidence: 4</ref> “as a significant decrease in the capacity of the stabilizing system of the spine to maintain the intervertebral neutral zones within the physiological limits so that there is no neurological dysfunction, no major<br>deformity, and no incapacitating pain.”<br>The ability to maintain an efficient coordination between these systems would allow of the patient to function without undue stress on the tissues in the body. Panjabi suggests that a loss of integrity within the passive subsystem may make segments unstable unless the neuromuscular subsystem compensates for that loss.<ref name="1">Biely SA, Smith SS, Silfies SP. Clinical instability of the lumbar spine: diagnosis and intervention. Orthpaedic Physical Therapy Practice. 2006;18:11-19. Level of evidence: 4</ref>,<ref name="47">Lumbar instability. Elsevier et al. Chapter 37, p523 – 529, 2013. Level of evidence: 5</ref>, <ref name="81">Beazell JR, Mullins M, Grindstaff TL. Lumbar instability: an evolving and challenging concept. The Journal of Manual &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Manipulative Therapy. 2010;18(1):9-14.doi:10.1179/106698110X12595770849443. Level of evidence: 3A</ref><br><br>Within lumbar instability we distinguish functional (clinical) instability and structural (radiografic) instability. <ref name="18">18.Beazell J. R. (2010). Lumbar instability: an evolving and challenging concept. J Man Manip Ther., 18(1), p. 9–14 Level of evidence: 2A</ref> Functional instability, which can cause pain despite the absence of any radiological anomaly, can be defined as the loss of neuromotor capability to control segmental movement during mid-range. Whereas structural or mechanical instability can be defined as the disruption of passive stabilisers, which limit the excessive segmental end range of motion (ROM). There is also a possibility to have a combined instability.<ref name="81">Beazell JR, Mullins M, Grindstaff TL. Lumbar instability: an evolving and challenging concept. The Journal of Manual &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Manipulative Therapy. 2010;18(1):9-14. doi:10.1179/106698110X12595770849443. Level of evidence: 3A</ref><br><br>T. Barz etal. <ref name="82">T. Barza, M. Melloh etal. A conceptual model of compensation/decompensation in lumbar segmental instability. Medical Hypotheses. Volume 83, Issue 3, SeptemberfckLR fckLRfckLR2014, Pages 312–316 Level of evidence: 4</ref> proposed a new conceptual model of compensation/decompensation in lumbar segmental instability (LSI). In LSI, structural deterioration of the lumbar disc initiates a degenerative cascade of segmental instability (see figure 1). Over time, radiographic signs become<br>visible (see etiology). Influenced by non-functional factors (psychosocial factors), functional elements of the spine (ligaments, muscles) allow a compensation of degeneration.This may lead to an alleviation of clinical symptoms. In return, the target condition of decompensation of LSI may cause the new occurrence of symptoms and pain. Individual differences of identical structural disorders could be explained by compensated or decompensated LSI leading to changes in clinical symptoms and pain. | <u></u>Lumbar instability is an important cause of low back pain and can be associated with substantial disability.<ref name="82">T. Barza, M. Melloh etal. A conceptual model of compensation/decompensation in lumbar segmental instability. Medical Hypotheses. Volume 83, Issue 3, September 2014, Pages 312–316 Level of evidence: 4</ref> The word ‘instability’ is still poorly defined. But it is most widely believed that the loss of a normal pattern of spinal motion causes pain and/or neurologic dysfunction. The American Academy of Orthopaedics Surgeons <ref name="4">American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeon : A glossary on spinal terminology. Chicage 1985</ref> state: ‘Segmental instability is an abnormal response to applied loads, characterized by motion in motion segments beyond normal constraints.’ Panjabi published a spinal stabilization system represented by 3 subsystems:<br> the passive, the active and the neural control subsystem.<ref name="2">Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part I. Function, dysfunction, adaptation, and enhancement. J Spinal Dis. 1992;5:383-389. Level of evidence: 4</ref><br> Segmental instability is defined by Panjabi <ref name="3">Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part II. Neutral zone and instability hypothesis. J Spinal Dis. 1992;5:390-397. Level of evidence: 4</ref> “as a significant decrease in the capacity of the stabilizing system of the spine to maintain the intervertebral neutral zones within the physiological limits so that there is no neurological dysfunction, no major<br>deformity, and no incapacitating pain.”<br>The ability to maintain an efficient coordination between these systems would allow of the patient to function without undue stress on the tissues in the body. Panjabi suggests that a loss of integrity within the passive subsystem may make segments unstable unless the neuromuscular subsystem compensates for that loss.<ref name="1">Biely SA, Smith SS, Silfies SP. Clinical instability of the lumbar spine: diagnosis and intervention. Orthpaedic Physical Therapy Practice. 2006;18:11-19. Level of evidence: 4</ref>,<ref name="47">Lumbar instability. Elsevier et al. Chapter 37, p523 – 529, 2013. Level of evidence: 5</ref>, <ref name="81">Beazell JR, Mullins M, Grindstaff TL. Lumbar instability: an evolving and challenging concept. The Journal of Manual &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Manipulative Therapy. 2010;18(1):9-14.doi:10.1179/106698110X12595770849443. Level of evidence: 3A</ref><br><br>Within lumbar instability we distinguish functional (clinical) instability and structural (radiografic) instability. <ref name="18">18.Beazell J. R. (2010). Lumbar instability: an evolving and challenging concept. J Man Manip Ther., 18(1), p. 9–14 Level of evidence: 2A</ref> Functional instability, which can cause pain despite the absence of any radiological anomaly, can be defined as the loss of neuromotor capability to control segmental movement during mid-range. Whereas structural or mechanical instability can be defined as the disruption of passive stabilisers, which limit the excessive segmental end range of motion (ROM). There is also a possibility to have a combined instability.<ref name="81">Beazell JR, Mullins M, Grindstaff TL. Lumbar instability: an evolving and challenging concept. The Journal of Manual &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Manipulative Therapy. 2010;18(1):9-14. doi:10.1179/106698110X12595770849443. Level of evidence: 3A</ref><br><br>T. Barz etal. <ref name="82">T. Barza, M. Melloh etal. A conceptual model of compensation/decompensation in lumbar segmental instability. Medical Hypotheses. Volume 83, Issue 3, SeptemberfckLR fckLRfckLR2014, Pages 312–316 Level of evidence: 4</ref> proposed a new conceptual model of compensation/decompensation in lumbar segmental instability (LSI). In LSI, structural deterioration of the lumbar disc initiates a degenerative cascade of segmental instability (see figure 1). Over time, radiographic signs become<br>visible (see etiology). Influenced by non-functional factors (psychosocial factors), functional elements of the spine (ligaments, muscles) allow a compensation of degeneration.This may lead to an alleviation of clinical symptoms. In return, the target condition of decompensation of LSI may cause the new occurrence of symptoms and pain. Individual differences of identical structural disorders could be explained by compensated or decompensated LSI leading to changes in clinical symptoms and pain. | ||

[[Image:Figure A.jpg]]<br> Figure 1 | [[Image:Figure A.jpg]]<br> Figure 1 | ||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy<br> == | == Clinically Relevant Anatomy<br> == | ||

The lumbar spine is intended to be very strong, so it can protect the sensitive spinal cord and spinal nerve roots and it has to cary<br> the most weight. Having regard to the form of the joints in the lumbar region, flexion and extension are the main motion directions. <ref name="5">Kisher, S. Lumbar Spine Anatomy (overview), 2015. Level of evidence: 5</ref><br><br>Panjabi’s spinal stabilization system<ref name="2">Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part I. Function, dysfunction, adaptation, and enhancement. J Spinal Dis. 1992;5:383-389. Level of evidence: 4</ref>,<ref>Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part II. Neutral zone and instability hypothesis. J Spinal Dis. 1992;5:390-397. Level of evidence: 4</ref>:<br>- Passive subsystem: intervertebral disc, ligaments, facet joints and capsules, vertebrae and passive muscle support<br>- active subsystem: spinal muscles and tendons, thoracolumbar fascia<br>- neural control system: nerves and central nervous system<br><br>The passive subsystem plays its most important stabilizing role in the elastic zone (near endrange) of spinal ROM.<br>Flexion of the spine is mostly stabilized by the posterior ligaments (interspinous and supraspinous ligaments), the facet joints, <br>the joint capsules and the intervertebral discs.<br>End-range extension is stabilized primarily by the anterior longitudinal ligament, the anterior aspect of the annulus fibrosus and<br> the facet joints. <ref name="47">Lumbar instability. Elsevier et al. Chapter 37, p523 – 529, 2013. Level of evidence: 5</ref><br><br>The neuromotor control subsystem controls segmental motion during the mid-range, while the osseoligamentous (passive)<br> subsystem limits segmental motion at the extremes of lumbar motion.<ref name="80">80. Alyazedi FM, Lohman EB, Wesley Swen R, Bahjri K. The inter-rater reliability of clinical tests that best predict the subclassification of lumbar segmental instability: structural, functional and combined instability. The Journal of Manual &amp;amp;amp;amp; Manipulative Therapy. 2015;23(4):197-204. Level of evidence: 3B</ref><br><br>The neutral zone is defined as a portion of the total physiologic range of intervertebral motion. The total physiologic range involves a <br>neutral zone and an elastic zone. The neutral zone, is the zone of movement close to the neutral position of the segment, a zone in<br> which movement occurs with little resistance. The elastic zone starts at the end of the neutral zone and stops at the end of physiologic <br>range of motion. <ref name="1">Biely SA, Smith SS, Silfies SP. Clinical instability of the lumbar spine: diagnosis and intervention. Orthpaedic Physical Therapy Practice. 2006;18:11-19. Level of evidence: 4</ref>,<ref name="3">Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part II. Neutral zone and instability hypothesis. J Spinal Dis. 1992;5:390-397. Level of evidence: 4</ref><br><br>[[Image:Figuur panjabi.jpg|thumb]]<br> | The lumbar spine is intended to be very strong, so it can protect the sensitive spinal cord and spinal nerve roots and it has to cary<br> the most weight. Having regard to the form of the joints in the lumbar region, flexion and extension are the main motion directions. <ref name="5">Kisher, S. Lumbar Spine Anatomy (overview), 2015. Level of evidence: 5</ref><br><br>Panjabi’s spinal stabilization system<ref name="2">Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part I. Function, dysfunction, adaptation, and enhancement. J Spinal Dis. 1992;5:383-389. Level of evidence: 4</ref>,<ref>Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part II. Neutral zone and instability hypothesis. J Spinal Dis. 1992;5:390-397. Level of evidence: 4</ref>:<br>- Passive subsystem: intervertebral disc, ligaments, facet joints and capsules, vertebrae and passive muscle support<br>- active subsystem: spinal muscles and tendons, thoracolumbar fascia<br>- neural control system: nerves and central nervous system<br><br>The passive subsystem plays its most important stabilizing role in the elastic zone (near endrange) of spinal ROM.<br>Flexion of the spine is mostly stabilized by the posterior ligaments (interspinous and supraspinous ligaments), the facet joints, <br>the joint capsules and the intervertebral discs.<br>End-range extension is stabilized primarily by the anterior longitudinal ligament, the anterior aspect of the annulus fibrosus and<br> the facet joints. <ref name="47">Lumbar instability. Elsevier et al. Chapter 37, p523 – 529, 2013. Level of evidence: 5</ref><br><br>The neuromotor control subsystem controls segmental motion during the mid-range, while the osseoligamentous (passive)<br> subsystem limits segmental motion at the extremes of lumbar motion.<ref name="80">80. Alyazedi FM, Lohman EB, Wesley Swen R, Bahjri K. The inter-rater reliability of clinical tests that best predict the subclassification of lumbar segmental instability: structural, functional and combined instability. The Journal of Manual &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Manipulative Therapy. 2015;23(4):197-204. Level of evidence: 3B</ref><br><br>The neutral zone is defined as a portion of the total physiologic range of intervertebral motion. The total physiologic range involves a <br>neutral zone and an elastic zone. The neutral zone, is the zone of movement close to the neutral position of the segment, a zone in<br> which movement occurs with little resistance. The elastic zone starts at the end of the neutral zone and stops at the end of physiologic <br>range of motion. <ref name="1">Biely SA, Smith SS, Silfies SP. Clinical instability of the lumbar spine: diagnosis and intervention. Orthpaedic Physical Therapy Practice. 2006;18:11-19. Level of evidence: 4</ref>,<ref name="3">Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part II. Neutral zone and instability hypothesis. J Spinal Dis. 1992;5:390-397. Level of evidence: 4</ref><br><br>[[Image:Figuur panjabi.jpg|thumb]]<br> | ||

For more detailed anatomy:<br>http://www.physio-pedia.com/Lumbosacral_Biomechanics<br> | For more detailed anatomy:<br>http://www.physio-pedia.com/Lumbosacral_Biomechanics<br> | ||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

A constant morphological modification of the spine alters the biomechanical loading from back muscles, ligaments, and joints, and can harvest back injuries.<ref name="30">Puntumetakul, R. et all., Prevalence and individual risk factors associated with clinical lumbar instability in rice farmers with low back pain, Dovepress, 2014. Level of evicence: 2B</ref>Granata et all., described that body mass, task asymmetry, and level of experience affected the scale and variability of spinal load during repeated lifting efforts.<ref name="31">Granata, K. et all., Cost–Benefit of Muscle Cocontraction in Protecting Against Spinal Instability, occupational Health/Ergonomics, 2000. Level of evidence: 2B</ref> In older people, bending and lifting activities produce loads on the spine that exceed the failure of vertebrae with low bone mineral density, which is linked with spinal degeneration. The degenerative transformation has influence on the intervertebral discs, ligament and bone.<ref name="30" /> | A constant morphological modification of the spine alters the biomechanical loading from back muscles, ligaments, and joints, and can harvest back injuries.<ref name="30">Puntumetakul, R. et all., Prevalence and individual risk factors associated with clinical lumbar instability in rice farmers with low back pain, Dovepress, 2014. Level of evicence: 2B</ref>Granata et all., described that body mass, task asymmetry, and level of experience affected the scale and variability of spinal load during repeated lifting efforts.<ref name="31">Granata, K. et all., Cost–Benefit of Muscle Cocontraction in Protecting Against Spinal Instability, occupational Health/Ergonomics, 2000. Level of evidence: 2B</ref> In older people, bending and lifting activities produce loads on the spine that exceed the failure of vertebrae with low bone mineral density, which is linked with spinal degeneration. The degenerative transformation has influence on the intervertebral discs, ligament and bone.<ref name="30" /> | ||

The estimated prevalence of low back pain due to lumbar segmental instability is about 33% for patients with functional instability, compared to 57% for patients with evidence of structural instability, as indicated by positive flexion–extension radiograph. <ref name="35">Abdullah M .Alqarni et al. Clinical tests to diagnose lumbar segmental instability : a systematic review. Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. March 2011. Level of evidence : 2A</ref>, <ref name="80">Alyazedi FM, Lohman EB, Wesley Swen R, Bahjri K. The inter-rater reliability of clinical tests that best predict the subclassification of lumbar segmental instability: structural, functional and combined instability. The Journal of Manual &amp;amp; Manipulative Therapy. 2015;23(4):197-204. Level of evidence: 3B</ref><br> | The estimated prevalence of low back pain due to lumbar segmental instability is about 33% for patients with functional instability, compared to 57% for patients with evidence of structural instability, as indicated by positive flexion–extension radiograph. <ref name="35">Abdullah M .Alqarni et al. Clinical tests to diagnose lumbar segmental instability : a systematic review. Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. March 2011. Level of evidence : 2A</ref>, <ref name="80">Alyazedi FM, Lohman EB, Wesley Swen R, Bahjri K. The inter-rater reliability of clinical tests that best predict the subclassification of lumbar segmental instability: structural, functional and combined instability. The Journal of Manual &amp;amp;amp; Manipulative Therapy. 2015;23(4):197-204. Level of evidence: 3B</ref><br> | ||

== Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | == Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | ||

| Line 136: | Line 136: | ||

If a CT scan shows a gap in the facet joints during rotation of the trunk, this could be an indirect sign of spinal instability. | If a CT scan shows a gap in the facet joints during rotation of the trunk, this could be an indirect sign of spinal instability. | ||

→ <u></u><u>Quantitative Stability Index (QSI)</u><span style="font-size: 13.28px;"><ref name="40">Ferrari et al. A literature review of clinical tests for lumbar instability in low back pain&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: validity and applicability in clinical practice. Chiropractic &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Manual Therapies. 2015 level of evidence: 2A</ref> <sup>LOE 2A</sup></span> | → <u></u><u>Quantitative Stability Index (QSI)</u><span style="font-size: 13.28px;"><ref name="40">Ferrari et al. A literature review of clinical tests for lumbar instability in low back pain&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: validity and applicability in clinical practice. Chiropractic &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Manual Therapies. 2015 level of evidence: 2A</ref> <sup>LOE 2A</sup></span> | ||

QSI is a novel objective test for sagittal plane lumbar instability. | QSI is a novel objective test for sagittal plane lumbar instability. | ||

| Line 203: | Line 203: | ||

- sensitivity: 37 <br>- specificity: 73 LR+: 1,4<br>- LR-: 0,9 <br> {{#ev:youtube|FCmYMfv7Sm8|300}}<br>https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yb0hBo-51gY <br><br> •<u>Apprehension sign</u> : <br>The examiner asks the patient if he or she has a sensation of lumbar collapse because of the low back pain while performing ordinary acts like bending back and forward , bending from side to side , sitting down or standig up. The test was positive if the patient had a sensation of lumbar collapse. <ref name="47" />The condition has a unique clinical presentation that displays its symptoms and movement dysfunction within the neutral zone of the motion segment. The loosening of the motion segment secondary to injury and associated dysfunction of the local muscle system renders it biomechanically vulnerable in the neutral zone. The clinical diagnosis of this chronic low back pain condition is based on the report of pain and the observation of movement dysfunction within the neutral zone and the associated finding of excessive intervertebral motion at the symptomatic level. Four different clinical patterns are described based on the directional nature of the injury and the manifestation of the patient's symptoms and motor dysfunction. A specific stabilizing exercise intervention based on a motor learning model is proposed and evidence for the efficacy of the approach provided.<ref>P.B. O'Sullivan. Masterclass. Lumbar segmental ‘instability’: clinical presentation and specific stabilizing exercise management. Manual therapy Volume 5, Issue 1, Pages 2–12, February 2000. Level of evidence: 2B</ref><sup>,</sup><ref>James R Beazell, Melise Mullins and Terry L Grindstaff .Lumbar instability: an evolving and challenging concept. J Man Manip Ther. 2010 Mar; 18(1): 9–14. Level of evidence: 2A</ref> <ref name="26">Kasai, Yuichi, et al. "A new evaluation method for lumbar spinal instability: passive lumbar extension test." Physical therapy 86.12 (2006): 1661-1667.fckLRLevel of evidence: 3b</ref> | - sensitivity: 37 <br>- specificity: 73 LR+: 1,4<br>- LR-: 0,9 <br> {{#ev:youtube|FCmYMfv7Sm8|300}}<br>https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yb0hBo-51gY <br><br> •<u>Apprehension sign</u> : <br>The examiner asks the patient if he or she has a sensation of lumbar collapse because of the low back pain while performing ordinary acts like bending back and forward , bending from side to side , sitting down or standig up. The test was positive if the patient had a sensation of lumbar collapse. <ref name="47" />The condition has a unique clinical presentation that displays its symptoms and movement dysfunction within the neutral zone of the motion segment. The loosening of the motion segment secondary to injury and associated dysfunction of the local muscle system renders it biomechanically vulnerable in the neutral zone. The clinical diagnosis of this chronic low back pain condition is based on the report of pain and the observation of movement dysfunction within the neutral zone and the associated finding of excessive intervertebral motion at the symptomatic level. Four different clinical patterns are described based on the directional nature of the injury and the manifestation of the patient's symptoms and motor dysfunction. A specific stabilizing exercise intervention based on a motor learning model is proposed and evidence for the efficacy of the approach provided.<ref>P.B. O'Sullivan. Masterclass. Lumbar segmental ‘instability’: clinical presentation and specific stabilizing exercise management. Manual therapy Volume 5, Issue 1, Pages 2–12, February 2000. Level of evidence: 2B</ref><sup>,</sup><ref>James R Beazell, Melise Mullins and Terry L Grindstaff .Lumbar instability: an evolving and challenging concept. J Man Manip Ther. 2010 Mar; 18(1): 9–14. Level of evidence: 2A</ref> <ref name="26">Kasai, Yuichi, et al. "A new evaluation method for lumbar spinal instability: passive lumbar extension test." Physical therapy 86.12 (2006): 1661-1667.fckLRLevel of evidence: 3b</ref> | ||

- sensitivity: 18<br>- specificity: 88 LR+: 1,6<br>- LR-: 0,9 <br><br>In acute overt instability, stabilization of the spine is required in all cases. In this context, medical treatment refers to the use of external bracing for spine stabilization. If instability is due to an osseous fracture, if the fracture fragments can be reduced to near-anatomic alignment, and if there is no significant neural compression after reduction, the patient may be treated nonsurgically with a brace until the fracture heals.<br><br>In anticipated instability (eg, extensive discitis and osteomyeli)<br>The majorty of the tests has high specificity but low sensitivity. Data suggest that PLE is the most appropriate tests to detect lumbar instability in specific LBP. The PLE test ( = Passive Lumbar Extension test) has a sensitivity of 84% , a specificity of 90% , a LR+ rate of 8,8 and an LR- rate of 0,2.<ref>Abdullah M .Alqarni et al. Clinical tests to diagnose lumbar segmental instability&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: a systematic review. Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. March 2011. Level of evidence&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: 2A</ref><sup>,</sup><ref>Ferrari et al. A literature review of clinical tests for lumbar instability in low back pain&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: validity and applicability in clinical practice. Chiropractic &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Manual Therapies. 2015. Level of evidence&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: 2A</ref><sup>,</sup><ref name="57">Silvano Ferarri et al., A literature review of clinical tests for lumbar instability in low back pain: validity and applicability in clinical practice. Chiropr Man Therap., April 2015; 23:14. Level of evidene: 2A</ref><sup></sup><br> | - sensitivity: 18<br>- specificity: 88 LR+: 1,6<br>- LR-: 0,9 <br><br>In acute overt instability, stabilization of the spine is required in all cases. In this context, medical treatment refers to the use of external bracing for spine stabilization. If instability is due to an osseous fracture, if the fracture fragments can be reduced to near-anatomic alignment, and if there is no significant neural compression after reduction, the patient may be treated nonsurgically with a brace until the fracture heals.<br><br>In anticipated instability (eg, extensive discitis and osteomyeli)<br>The majorty of the tests has high specificity but low sensitivity. Data suggest that PLE is the most appropriate tests to detect lumbar instability in specific LBP. The PLE test ( = Passive Lumbar Extension test) has a sensitivity of 84% , a specificity of 90% , a LR+ rate of 8,8 and an LR- rate of 0,2.<ref>Abdullah M .Alqarni et al. Clinical tests to diagnose lumbar segmental instability&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: a systematic review. Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. March 2011. Level of evidence&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: 2A</ref><sup>,</sup><ref>Ferrari et al. A literature review of clinical tests for lumbar instability in low back pain&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: validity and applicability in clinical practice. Chiropractic &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Manual Therapies. 2015. Level of evidence&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: 2A</ref><sup>,</sup><ref name="57">Silvano Ferarri et al., A literature review of clinical tests for lumbar instability in low back pain: validity and applicability in clinical practice. Chiropr Man Therap., April 2015; 23:14. Level of evidene: 2A</ref><sup></sup><br> | ||

== Medical Management <br> == | == Medical Management <br> == | ||

A Significant subgroup within chronic low back pain patients, are the ones with lumbar segmental instability.<ref name="64">Sedat Dalbayrak. “Differences between the over tand chronic instability and the reflection of these differences in the treatment” http://www.turknorosirurji.org.tr/TNDData/Books/253/diffrences-between-the-overt-and-chronic-instability-and-the-reflection-of-these.pdf Level of evidence: 2a</ref> <sup>level of evidence 2A</sup> Medical treatment and surgery is more often recommended in chronic overt instability and covert instability, than in the other cases. When there’s no direct risk for neurological damage or side effect, the first medical treatment for patients with acute overt instability should be external bracing before surgery. This might even solve the patients complains when the cause for instability is a fracture of the spine.<ref name="63">Peyman Pakzaban, MD “Spinal instability and spinal fusion surgery treatment &amp;amp; management” WebMed LLC Jan 2016 http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1343720-treatment. Level of evidence: 4</ref> <sup>level of evidence 4</sup><br>But when conservative treatment fails, this may be reconsidered. | A Significant subgroup within chronic low back pain patients, are the ones with lumbar segmental instability.<ref name="64">Sedat Dalbayrak. “Differences between the over tand chronic instability and the reflection of these differences in the treatment” http://www.turknorosirurji.org.tr/TNDData/Books/253/diffrences-between-the-overt-and-chronic-instability-and-the-reflection-of-these.pdf Level of evidence: 2a</ref> <sup>level of evidence 2A</sup> Medical treatment and surgery is more often recommended in chronic overt instability and covert instability, than in the other cases. When there’s no direct risk for neurological damage or side effect, the first medical treatment for patients with acute overt instability should be external bracing before surgery. This might even solve the patients complains when the cause for instability is a fracture of the spine.<ref name="63">Peyman Pakzaban, MD “Spinal instability and spinal fusion surgery treatment &amp;amp;amp; management” WebMed LLC Jan 2016 http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1343720-treatment. Level of evidence: 4</ref> <sup>level of evidence 4</sup><br>But when conservative treatment fails, this may be reconsidered. | ||

Another part of the medical treatment is medication. Depending on the complains of the patient and de physiological indication, analgesics, anti-inflammatories, muscle relaxants can be prescript.<br><br> | Another part of the medical treatment is medication. Depending on the complains of the patient and de physiological indication, analgesics, anti-inflammatories, muscle relaxants can be prescript.<br><br> | ||

| Line 231: | Line 231: | ||

However, despite the fact that indications for the procedure are uncertain, that costs and complication rates are higher than for other surgical procedures performed on the spine, and that long-term outcomes are uncertain, the rate of lumbar spinal fusion is increasing rapidly in the United States.<ref name="43">Deyo RA, Ciol MA, Cherkin DC, et al. Lumbar spinal fusion: a cohort study of complications, reoperations, and resource used in the Medicare population. Spine 1993;18:1463–70. Level of evidence: 2B</ref> <sup>Level evidence: 2B</sup>,<ref name="44">Davis H. Increasing rates of cervical and lumbar spine surgery in the United States, 1979–1990. Spine 1994;19:1117–1124.Level of evidence: 2A</ref> <sup>Level evidence: 2A</sup> The rate of back surgery and especially of spinal fusion operations is at least 40% higher in the US than in any other country and is five times higher than in the UK.<ref name="45">Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Loeser JD, et al. An international comparison of back surgery rates. Spine 1994;19:1201–6. Level of evidence: 2B</ref> <sup>Level evidence: 2B</sup> Although there have been no randomized trials evaluating the effectiveness of lumbar fusion for spinal instability, the feeling remains that the operation should be reserved for patients with severe symptoms and radiographic evidence of excessive motion (greater than 5 mm translation or 10° of rotation) who fail to respond to a trial of non-surgical treatment.<ref name="46">Sonntag VKH, Marciano FF. Is fusion indicated for lumbar spinal disorders? Spine 1995;20(suppl):138S–42S. Level of evidence: 4</ref> <sup>Level evidence: 4</sup> The latter should consist of a combination of patient education, physical training and sclerosing injections.<ref name="47">Lumbar instability. Elsevier et al. Chapter 37, p523 – 529, 2013. Level of evidence: 5</ref> <sup>Level evidence: 5</sup> | However, despite the fact that indications for the procedure are uncertain, that costs and complication rates are higher than for other surgical procedures performed on the spine, and that long-term outcomes are uncertain, the rate of lumbar spinal fusion is increasing rapidly in the United States.<ref name="43">Deyo RA, Ciol MA, Cherkin DC, et al. Lumbar spinal fusion: a cohort study of complications, reoperations, and resource used in the Medicare population. Spine 1993;18:1463–70. Level of evidence: 2B</ref> <sup>Level evidence: 2B</sup>,<ref name="44">Davis H. Increasing rates of cervical and lumbar spine surgery in the United States, 1979–1990. Spine 1994;19:1117–1124.Level of evidence: 2A</ref> <sup>Level evidence: 2A</sup> The rate of back surgery and especially of spinal fusion operations is at least 40% higher in the US than in any other country and is five times higher than in the UK.<ref name="45">Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Loeser JD, et al. An international comparison of back surgery rates. Spine 1994;19:1201–6. Level of evidence: 2B</ref> <sup>Level evidence: 2B</sup> Although there have been no randomized trials evaluating the effectiveness of lumbar fusion for spinal instability, the feeling remains that the operation should be reserved for patients with severe symptoms and radiographic evidence of excessive motion (greater than 5 mm translation or 10° of rotation) who fail to respond to a trial of non-surgical treatment.<ref name="46">Sonntag VKH, Marciano FF. Is fusion indicated for lumbar spinal disorders? Spine 1995;20(suppl):138S–42S. Level of evidence: 4</ref> <sup>Level evidence: 4</sup> The latter should consist of a combination of patient education, physical training and sclerosing injections.<ref name="47">Lumbar instability. Elsevier et al. Chapter 37, p523 – 529, 2013. Level of evidence: 5</ref> <sup>Level evidence: 5</sup> | ||

A good fusion still doesn’t guarantee pain relief, because the presence of micromotion between the vertebrae. <ref name="71">Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part 1. Function, dysfunction adaption and enhancement. J Spinal Disord 1992;5:383-9.</ref> <sup>Level evidence: 2A</sup> A solid fusion at one segment doesn’t prevent micromotion in the rest of the spinal unit. <ref name="72">Farfan Hf “Mechanical Disorders of the low back” Philadelphia, Lea &amp;amp; Febiger 1973 Level of evidence: 2a</ref><sup>Level evidence: 2A</sup><br><br> <br><br> | A good fusion still doesn’t guarantee pain relief, because the presence of micromotion between the vertebrae. <ref name="71">Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part 1. Function, dysfunction adaption and enhancement. J Spinal Disord 1992;5:383-9.</ref> <sup>Level evidence: 2A</sup> A solid fusion at one segment doesn’t prevent micromotion in the rest of the spinal unit. <ref name="72">Farfan Hf “Mechanical Disorders of the low back” Philadelphia, Lea &amp;amp;amp; Febiger 1973 Level of evidence: 2a</ref><sup>Level evidence: 2A</sup><br><br> <br><br> | ||

== Physical Therapy Management <br> == | == Physical Therapy Management <br> == | ||

Revision as of 21:10, 2 February 2017

Original Editors - Anke Jughters, <topcontributors>Liese Bosmans</topcontributors>

Top Contributors - Sam Van de Mosselaer, Tessa de Jongh, Anke Jughters, Andeela Hafeez, Admin, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Kai A. Sigel, Rachael Lowe, Elien Clerix, WikiSysop, 127.0.0.1, Tony Varela, Liese Bosman, Vandoorne Ben, Shaimaa Eldib, Tony Lowe, Elaine Lonnemann, Robert Pierce and Mats Vandervelde

Search strategy[edit | edit source]

• Databases searched: Physiopedia , Pedro , Pubmed

• Keywords searched : ‘Lumbar Instability’, ‘spine instability’, ‘exercises lumbar instability’ ,

‘Lumbar spine instability‘ , ‘‘Lumbar instability treatment’, ‘medical management lumbar

instability’, ‘low back school’ , ‘Lumbar instability physical examination’, ‘segmental instability’, ‘

physical mangement lumbar instability’

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Lumbar instability is an important cause of low back pain and can be associated with substantial disability.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title The word ‘instability’ is still poorly defined. But it is most widely believed that the loss of a normal pattern of spinal motion causes pain and/or neurologic dysfunction. The American Academy of Orthopaedics Surgeons Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title state: ‘Segmental instability is an abnormal response to applied loads, characterized by motion in motion segments beyond normal constraints.’ Panjabi published a spinal stabilization system represented by 3 subsystems:

the passive, the active and the neural control subsystem.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Segmental instability is defined by Panjabi Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title “as a significant decrease in the capacity of the stabilizing system of the spine to maintain the intervertebral neutral zones within the physiological limits so that there is no neurological dysfunction, no major

deformity, and no incapacitating pain.”

The ability to maintain an efficient coordination between these systems would allow of the patient to function without undue stress on the tissues in the body. Panjabi suggests that a loss of integrity within the passive subsystem may make segments unstable unless the neuromuscular subsystem compensates for that loss.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title,Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title, Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Within lumbar instability we distinguish functional (clinical) instability and structural (radiografic) instability. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Functional instability, which can cause pain despite the absence of any radiological anomaly, can be defined as the loss of neuromotor capability to control segmental movement during mid-range. Whereas structural or mechanical instability can be defined as the disruption of passive stabilisers, which limit the excessive segmental end range of motion (ROM). There is also a possibility to have a combined instability.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

T. Barz etal. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title proposed a new conceptual model of compensation/decompensation in lumbar segmental instability (LSI). In LSI, structural deterioration of the lumbar disc initiates a degenerative cascade of segmental instability (see figure 1). Over time, radiographic signs become

visible (see etiology). Influenced by non-functional factors (psychosocial factors), functional elements of the spine (ligaments, muscles) allow a compensation of degeneration.This may lead to an alleviation of clinical symptoms. In return, the target condition of decompensation of LSI may cause the new occurrence of symptoms and pain. Individual differences of identical structural disorders could be explained by compensated or decompensated LSI leading to changes in clinical symptoms and pain.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

[edit | edit source]

The lumbar spine is intended to be very strong, so it can protect the sensitive spinal cord and spinal nerve roots and it has to cary

the most weight. Having regard to the form of the joints in the lumbar region, flexion and extension are the main motion directions. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Panjabi’s spinal stabilization systemCite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title,[1]:

- Passive subsystem: intervertebral disc, ligaments, facet joints and capsules, vertebrae and passive muscle support

- active subsystem: spinal muscles and tendons, thoracolumbar fascia

- neural control system: nerves and central nervous system

The passive subsystem plays its most important stabilizing role in the elastic zone (near endrange) of spinal ROM.

Flexion of the spine is mostly stabilized by the posterior ligaments (interspinous and supraspinous ligaments), the facet joints,

the joint capsules and the intervertebral discs.

End-range extension is stabilized primarily by the anterior longitudinal ligament, the anterior aspect of the annulus fibrosus and

the facet joints. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

The neuromotor control subsystem controls segmental motion during the mid-range, while the osseoligamentous (passive)

subsystem limits segmental motion at the extremes of lumbar motion.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

The neutral zone is defined as a portion of the total physiologic range of intervertebral motion. The total physiologic range involves a

neutral zone and an elastic zone. The neutral zone, is the zone of movement close to the neutral position of the segment, a zone in

which movement occurs with little resistance. The elastic zone starts at the end of the neutral zone and stops at the end of physiologic

range of motion. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title,Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

For more detailed anatomy:

http://www.physio-pedia.com/Lumbosacral_Biomechanics

Epidemiology /Etiology

[edit | edit source]

Lumbar spinal instability may be caused by Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title :

• degenerative disease

• facet joint hypertrophy

• postoperative status

• postoperative spinal fusion

• trauma to spine or its surrounding structures

• development disorders, like scoliosis and other congenital spine lesions

• infection

• tumors

Abnormal segmental motion noted on kinetic MR images is closely associated with disc degeneration, facet joint osteoarthritis, and the pathological characteristics of interspinous ligaments, ligamentum flavum (hypertrophy) and paraspinal muscles. Other spine pathology such as annular tears or traction spurs has also been associated with segmental instability. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

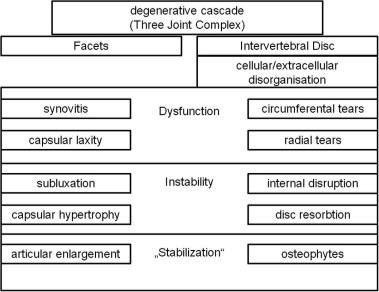

When a disorder or injury occurs, the whole motion segment is affected and the degenerative cascade begins which can lead to the symptoms and signs of LSI (see figure 2).

Firgure 2 Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

A constant morphological modification of the spine alters the biomechanical loading from back muscles, ligaments, and joints, and can harvest back injuries.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive titleGranata et all., described that body mass, task asymmetry, and level of experience affected the scale and variability of spinal load during repeated lifting efforts.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title In older people, bending and lifting activities produce loads on the spine that exceed the failure of vertebrae with low bone mineral density, which is linked with spinal degeneration. The degenerative transformation has influence on the intervertebral discs, ligament and bone.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

The estimated prevalence of low back pain due to lumbar segmental instability is about 33% for patients with functional instability, compared to 57% for patients with evidence of structural instability, as indicated by positive flexion–extension radiograph. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title, Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Patients with lumbar instability are commonly patients with chronical recurrent low back pain, a constant nagging pain which gradually increases. This pain can also be a residue of acute complaints.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title [LOE 2A]

There’s still a controversy about the exact meaning of the term lumbar instability.

Following characteristics can indicate lumbar instability Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title [LOE 2A], Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title [LOE 2A]:

- The feeling of instability, giving way.

- A visually observable or palpable hitch at a moving segment in the lumbar spine, mostly during change of position.

- Segmental shifts or hinging associated with the painful movement.

- Moving or jumping of the vertebra accompanied with pain in active trunk flexion or deflexion.

- An increased mobility at the concerned movement segment, mostly in passive segmental lumbar flexion and extension.

- Excessive intervertebral motion at the symptomatic level or an increased intersegmental motion at the level above the concerned movement segment.

- Local pain.

- Low back pain during long static load and deflexion.

- Pain during change of position and while bending or lifting.

- An abnormal motion sensation in postero-anterior movements of the vertebra.

- Decreased repositioning accuracy.

- Decreased postural control.

- Decreased activation of stabilizing muscles.

- Disruptions in the patterns of recruitment and co-contraction of the large trunk muscles (global muscle system) and small intrinsic muscles (local muscle system). This affects the timing of patterns of co-contraction, balance and reflexes.

- Pain and the observation of movement dysfunction within the neutral zone.

- A painful arc.

- Gowers sign: the inability to return to erect standing from forward bending without the use of the hands to assist this motion.

- Frequently crack or pop the back to reduce the symptoms, selfmanipulation.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

• Intervertebral disc prolapse

http://www.physio-pedia.com/Disc_Herniation

• Spondylosis

www.physio-pedia.com/Lumbar_Spondylosis

• Facet joint syndrome (arthritis of the facet joints)

http://www.physio-pedia.com/Facet_Joint_Syndrome

• Lumbar spine fracture

www.physio-pedia.com/Lumbar_Spine_Fracture

[1]• Spondylolisthesis

www.physio-pedia.com/Spondylolisthesis

• Hypermobility syndrome

www.physio-pedia.com/Hypermobility_Syndrome

• Osteoporosis

www.physio-pedia.com/Osteoporosis

• Sciatica

www.physio-pedia.com/Sciatica

• Degenerative disc disease

www.physio-pedia.com/Degenerative_Disc_Disease

• Rheumatoid arthritis

www.physio-pedia.com/Rheumatoid_Arthritis

• Lumbar compression fracture

www.physio-pedia.com/Lumbar_compression_fracture

Diagnostic Procedure[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis of lumbar instability is commonly based on the imaging finding of abnormal vertebral motion. This only shows anatomical instability and not functional instability. Abnormal translation and/or rotation around the x-, y-, and z-axes of the three-dimensional system by Panjabi and White can be found. Lumbar instability is mostly multidirectional, but the resulting displacement is evaluated in one plane at the time. Sagittal and coronal displacements are evaluated with radiographs, displacements on the axial plane are evaluated with computed tomographic (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR). Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title LOE 2A, Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title LOE 2A, Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title LOE 2A

Functional flexion-extension radiographs taken at the end-range of movement are the most frequently used, but show only the function of the passive stabilizing subsystem and fail to address the active and neural control subsystems.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title LOE 2A

The relationship between imaging instability and its symptoms remains difficult to appoint. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

→ Neutral radiography:Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive titleLOE 2A

Shows many indirect signs that are associated with spinal instability.

→ Functional radiography Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive titleLOE 2A

Functional radiography in the sagittal plane can occur in flexion and extension or with passive axial traction and compression. Intervertebral instability or abnormal motion between two vertebrae can be observed. Dynamic radiographs obtained in both flexion and extension, determine motion segment instability and can also indicate the lesions located in specific areas.

→ Magnetic resonance imagingCite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title LOE 2A, Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title LOE 2A

MR imaging is commonly considered to be the most accurate imaging method for diagnosing degenerative abnormalities of the spine and is often used for the diagnosis of patients with chronic low back pain.

→ Intraoperative measurement systemCite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title LOE 2A:

This technique is recently developed and implies in vivo measurements of vertebral segment displacement during the application of a controlled load to produce motion.

The operator grasps the spinous process to move it caudally.

A device is developed to preserve the supraspinal ligament after clearing the paravertebral muscles and hammering the two pins into the two spinous processes lying on either side of the lumbar vertebrae so the stability can be measured.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive titleLOE 2A

→ Computed tomographyCite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title LOE 2A :

CT can show spinal degenerative changes and facet joint orientation. It can demonstrate predisposing anatomic factors, such as facet joint asymmetry.

If a CT scan shows a gap in the facet joints during rotation of the trunk, this could be an indirect sign of spinal instability.

→ Quantitative Stability Index (QSI)Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title LOE 2A

QSI is a novel objective test for sagittal plane lumbar instability.

A QSI > 2 standard deviations from normal in an asymptomatic and radiographically normal population, would indicate that the amount of translation per degree of rotation is abnormal.

A QSI = 4 would indicate far greater instability.

Outcome Measures

[edit | edit source]

- Oswestry Disability Index: subjective percentage score of level of function (disability) in activities of daily living in those rehabilitating from low back pain.

Minimal detectable chance is 5-6 points and the minimum clinically important difference is 6 points.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Scores from 0% to 20% indicate minimal disability

20% to 40%, moderate disability

40% to 60%, severe disability;

60% to 80%, crippled

80% to 100%, bedbound or exaggerating Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Oswestry_Disability_Index

- Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale:

The Quebec back pain disability scale (QBPDS) is a condition-specific questionnaire developed to measure the level of functional disability for patients with low back pain.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

The end score will be between 0 (no limitation) and 100 (totally limited).

The minimum clinically important difference is 15 points when suffering acute low back pain of chronic low back pain.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Quebec_Back_Pain_Disability_Scale

- Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire:

This questionnaire is designed to assess self-rated physical disability caused by low back pain.

o When the score at intake is < 9 points; Minimal detectable change (MDC) = 6,7 points and the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) is 2-3 points.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

o When the score at intake is between 9-16: MDC = 4-5 points and MCID = 5-9 points.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title,Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

o When the score at intake is > 16 points: MDC = 8,6 points and MCID = 8-13 points.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

MIC absolute cutoff, minimal important change = 5 points for patients with low back pain. MIC (% imporovement from baseline) = 30%Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Roland%E2%80%90Morris_Disability_Questionnaire

- Patient Specific Functional Scale:

This useful questionnaire can be used to quantify activity limitation and measure functional outcome for patients with any orthopaedic condition.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

The Minimal detectable change (MDC) is for chronic pain = 2 points, for low back pain = 1,4 points and the minimum clinically important difference (MCID)= 2,0 points.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Stratford et alCite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title found the average of the MCID scores for 3 activities to be 0.8 (“small change”), 3.2 (“medium change”), and 4.3 (“large change”) PSFS points in patients with chronic low back pain.

Waddell Disability Index:

The WDI evaluates disability because of low back pain. The scale consists of nine items. These questions are answered with yes or no and are about impairments in activities of daily living (not related to a specific period). The final score is calculated by adding up positive items, and ranges from 0 to 9.21. ICCs = 0.79Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title,Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Physical examination[edit | edit source]

The physical examination may consist of multiple tests :

• Low midline sill sign:

First there is an inspection of the midline of the patient’s low back to detect the low midline sill sign. If lumbar lordosis increases and there is a sill like a capital “L” on the midline, the test is considered positive. Next the examiner palpates the interspinous space and evaluates the position of the upper spinous process in relation to the lower spinosus process.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title If the upper spinous process is displaced anterior to the lower spinous process, the test positive.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Figure 3

• Interspinous gap change during lumbar flexion – extension motion:

This test is used for the detection of lumbar instability. First there is an inspection of the low back to detect the interspinous gap change. The patient stands shoulder – width, flex his back and place both hands on an examination table. After inspection of the lower back in flexion, palpates and evaluates the physiotherapist the width of the individual interspinous spaced and the position of the upper spinous process in relation to the lower one.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

After this the physiotherapist will ask the patient to extend (to hollow) the low back while he evaluates the interspinous gap change during this motion. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title, Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Figure 4

• Sit – to – stand test:Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

The test is positive (there is an association with instability) if the person feels pain immediately when sitting down in a chair and if the pain is (partially) relieved by standing up.

The test result might vary (time of the day, type of seat, the patients’ symptom levels before the test).

- sensitivity: 30

- specificity: 100

- LR+: cannot be calculated

- LR-: 0,7

• Passive Accessory Intervertebral Movements ( = PAIVM): Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physiopedia.com/Manual_Therapy_Techniques_For_The_Lumbar_Spine#PPIVMs

- sensitivity: 46

- specificity: 81

- LR+: 2,4

- LR-: 0,7

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gAUFcaEw0I0

• Prone instability test : Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title,Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Prone_Instability_Test

- sensitivity: 61

- specificity: 57

- LR+: 1,4

- LR-: 0,7

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OrgoC3mKhXQ

[2]• Beighton hypermobility scale : Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title,Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

www.physio-pedia.com/Beighton_score

- sensitivity: 36

- specificity: 86

- LR+: 2,5

- LR-: 0,8

[3]• Passive Physiological Intervertebral Motion ( = PPIVM ):Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title,Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

http://www.physiopedia.com/Manual_Therapy_Techniques_For_The_Lumbar_Spine#PPIV Ms

The patient side lies. The test consisted of moving the patient’s spine through sagittal forward – bending ( flexion ) and backward – bending ( extension ) , using the lower extremities. Meanwhile the examiner palpates between the spinous process of the adjacent vertebrae to assess the motion taking place at each motion segment. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

PPIVM (flexion):

- sensitivity: 5 - specificity: 99,5

- LR+: 8,7 - LR-: 1,0

PPIVM (extention)

- sensitivity: 16 - specificity: 98

- LR+: 7,1 - LR-: 0,9

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HP6ZuG3NRNs

• Passive Lumbar Extension Test ( = PLE test ):

The patient is in prone position. The therapist elevates both lower extremities were elevated ( passive ) to a height of about 30cm. The knees maintain extended while gently pulling the legs. The examiner fixates T12 ventrocaudal. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title,Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

This test can also be done in lateral position of the patient with the legs bended. The test is positive if it provokes similar complaints.

- sensitivity: 84

- specificity: 90

- LR+: 8,8

- LR-: 0,2

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eUJw9pxcV-g

• Instability catch sign = active flexion test:

The patient bend his or her body forward as much as possible and then return to the neutral position. The test is positive when the patient isn’t able to return to the neutral position.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title, [2]

This test is a provocation test.

- sensitivity: 26

- specificity: 86 LR+: 1,8

- LR-: 0,9Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=63clj33mkHc

• Painful catch sign :

The patient is in supine position and then the examiner asks the patient to lift both lower extremities. The knees must be extended. Then the examiner asks the patient to return slowly to the start positon. If the lower extremities fell down instantly because of the low back pain , the test was positive. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

- sensitivity: 37

- specificity: 73 LR+: 1,4

- LR-: 0,9

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yb0hBo-51gY

•Apprehension sign :

The examiner asks the patient if he or she has a sensation of lumbar collapse because of the low back pain while performing ordinary acts like bending back and forward , bending from side to side , sitting down or standig up. The test was positive if the patient had a sensation of lumbar collapse. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive titleThe condition has a unique clinical presentation that displays its symptoms and movement dysfunction within the neutral zone of the motion segment. The loosening of the motion segment secondary to injury and associated dysfunction of the local muscle system renders it biomechanically vulnerable in the neutral zone. The clinical diagnosis of this chronic low back pain condition is based on the report of pain and the observation of movement dysfunction within the neutral zone and the associated finding of excessive intervertebral motion at the symptomatic level. Four different clinical patterns are described based on the directional nature of the injury and the manifestation of the patient's symptoms and motor dysfunction. A specific stabilizing exercise intervention based on a motor learning model is proposed and evidence for the efficacy of the approach provided.[3],[4] Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

- sensitivity: 18

- specificity: 88 LR+: 1,6

- LR-: 0,9

In acute overt instability, stabilization of the spine is required in all cases. In this context, medical treatment refers to the use of external bracing for spine stabilization. If instability is due to an osseous fracture, if the fracture fragments can be reduced to near-anatomic alignment, and if there is no significant neural compression after reduction, the patient may be treated nonsurgically with a brace until the fracture heals.

In anticipated instability (eg, extensive discitis and osteomyeli)

The majorty of the tests has high specificity but low sensitivity. Data suggest that PLE is the most appropriate tests to detect lumbar instability in specific LBP. The PLE test ( = Passive Lumbar Extension test) has a sensitivity of 84% , a specificity of 90% , a LR+ rate of 8,8 and an LR- rate of 0,2.[5],[6],Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

A Significant subgroup within chronic low back pain patients, are the ones with lumbar segmental instability.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title level of evidence 2A Medical treatment and surgery is more often recommended in chronic overt instability and covert instability, than in the other cases. When there’s no direct risk for neurological damage or side effect, the first medical treatment for patients with acute overt instability should be external bracing before surgery. This might even solve the patients complains when the cause for instability is a fracture of the spine.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title level of evidence 4

But when conservative treatment fails, this may be reconsidered.

Another part of the medical treatment is medication. Depending on the complains of the patient and de physiological indication, analgesics, anti-inflammatories, muscle relaxants can be prescript.

Surgerical management[edit | edit source]

Surgery should always be the last option, because it’s never without risks. The main problem of fusion is the disruption of the biomechanics of the rest of the spine; leading to adjacent level disease.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive titleLevel evidence: 1A

There are different ways to fuse a spine segment.

Anterior approach: The intervertebral disc is removed from a front approach (trough the abdomen) and replaced with bone graft or instrumentation.

Posterior approach: This surgery is either the same as the anterior approach, but from the back or there’s a fusion of a segment.

Combined approach: In some cases it’s not possible to complete the fusion only from the front or the back. In this scenario the surgeon will reach the spine from both sides.

Instrumented fusion: Utilisation of titanium, titanium-alloy, stainless steel or non-metallic material to replace the intervertebral disc.

Non-instrumented fusion: Also known as arthrodesis. This type of surgery uses bone graft to replace the original intervertebral disc.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Level evidence: 3A

The existing literature does not identify significant differences between unilateral instrumentation or bilateral in the lumbar spine. The most used fusion is single-level.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Level evidence: 1A

There’s also growing evidence for the use of minimally invasive spine surgery (MIS) instead of open surgery.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Level evidence: 2B

Still the indications for surgery are controversial and more research is much needed. The main problem lies in the definition and the diagnosis of lumbar instability. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Level evidence:2B

However, despite the fact that indications for the procedure are uncertain, that costs and complication rates are higher than for other surgical procedures performed on the spine, and that long-term outcomes are uncertain, the rate of lumbar spinal fusion is increasing rapidly in the United States.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Level evidence: 2B,Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Level evidence: 2A The rate of back surgery and especially of spinal fusion operations is at least 40% higher in the US than in any other country and is five times higher than in the UK.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Level evidence: 2B Although there have been no randomized trials evaluating the effectiveness of lumbar fusion for spinal instability, the feeling remains that the operation should be reserved for patients with severe symptoms and radiographic evidence of excessive motion (greater than 5 mm translation or 10° of rotation) who fail to respond to a trial of non-surgical treatment.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Level evidence: 4 The latter should consist of a combination of patient education, physical training and sclerosing injections.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Level evidence: 5

A good fusion still doesn’t guarantee pain relief, because the presence of micromotion between the vertebrae. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Level evidence: 2A A solid fusion at one segment doesn’t prevent micromotion in the rest of the spinal unit. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive titleLevel evidence: 2A

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

It’s important to understand Panjabi's hypothesis, that spinal stability is dependent on an interplay between the passive, active, and neural control systems. This indicates that you need to train different aspects to improve you spinal stability. The size of the neutral zone is also a better indicator of clinical spine instability than the overall rang of motion. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Level of evidence: 2A

Patient education is important in the treatment of patients with segmental instability.This education should not only focus on the moments that the patient should not perform. But it should motivate the patient to stay active, knowing which movements shouldn’t be or with great care performed. These movements are loaded flexion movements, as they may create a posterior shift of the disc. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title level of evidence 1A And any end-range positions of the lumbar spine should also be avoided because these overload the posterior passive stabilizing structures.

Physical therapy for segmental instability focuses on exercises designed to improve stability of the spine. As the lumbar erector spinae muscles are the primary source of extension torque for lifting tasks, strengthening of this muscle group has been supported.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title, level of evidence 1B

Intensive dynamic exercises for the extensors proved to be significantly superior to a regime of standard treatment of thermotherapy, massage and mild exercises in patients with recurrent LBP.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title,Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title,Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 1B

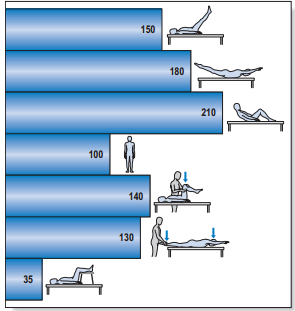

The abdominal muscles, particularly the transversus abdominis and oblique abdominals, have also been proposed as having an important role in stabilizing the spine by co-contracting in anticipation of a tested load. However, exercises proposed to address the abdominal muscles in an isolated manner usually involve some type of sit-up manœuvre that imposes dangerously high compressive and shear forces on the lumbar spine [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 5 ] and may provoke a posterior shift of the (unstable) disc (see figure 5).

Figure 5: Intradiscal pressure in % of that of the standing position

Alternative techniques should therefore be tested when training these muscles. Some authors strongly suggest that the transversus abdominis [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title, level of evidence 2A ] and the multifidus muscles make a specific contribution to the stability of the lower spine [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title, level of evidence 2B ] [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 2A ] and an exercise programme that proposes the retraining of the co-contraction pattern of the transversus abdominis and multifidus muscles has been described. [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 1C ]

The exercise programme is based on training the patient to draw in the abdominal wall while isometrically contracting the multifidus muscle, and consists of three different levels:

• First, specific localized stabilization training is given. Lying prone, sitting and standing upright, the patient performs the isometric abdominal drawing-in manœuvre with co-contraction of the lumbar multifidus muscles. = Segmental control over primary stabilizers (mainly TrA, deep multifidus, pelvic floor and diaphragm) [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title, level of evidence 5 ]

During this phase we also teach the patient about locale segmental control.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title A stabilizer is a very useful to teach this to your patient. The pressure should stay between 38 and 42 mmHg.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Level of evidence:4

• During the phase of general trunk stabilization, the co-contraction of the same muscles is carried out on all fours, and then elevating one arm forwards and/or the contralateral leg backwards, or on standing upright and elevating one arm forwards and/or bringing the contralateral leg backwards. = Exercises in closed chain, with low velocity and low load [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 5 ]

• Third, there is the stabilization training. Once accurate activation of the co-contraction pattern is achieved, training is given in functional movements, such as standing up from a sitting or lying position, bending forwards and backwards and turning. All daily activities are then integrated. A significant result from a randomized trial has recently been reported comparing this exercise programme with one of general exercise (swimming, walking, gymnastic exercises) in a group of patients with chronic LBP.[Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 1B ]= Exercises in open chain, with high velocity and load [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 5 ]

The training of this stabilisation muscles has positive results on pain control. Still it’s not entirely clear how this mechanism works. But we know that when the muscles contract, and especially when they do simultaneously, they compress the entire lumbar spine. This makes it harder for the joints and intervertebral discs to move in inefficient directions.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 2B

The training creates a rigid cylinder around the spine. An exercises program should always be individualised accordingly to the patients (pain) complains. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 2A

For excercises : www.physio-pedia.com/Exercises_for_Lumbar_Instability

The effectivity of back school program for treatment of low back pain and functional disability has been shown and is more effective than any educational intervention in general health status and in decreasing acetaminophen and NSAID intake. It was ineffective in the other quality of life domains, in pain, functional status, anxiety and depression. [Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title , level of evidence 1B ] Back school should be a part of the physical treatment, next to exercise and physical treatment modalities. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title, level of evidence: 1B

On Physiopedia : http://www.physio-pedia.com/Back_School

There moderate evidence suggested that back schools have better short- and intermediate-term effects on the functional status and pain than other treatments for patients with recurrent and chronic low back pain (LBP) Moderate evidence suggests that a back school for chronic LBP in an occupational setting are even more effective than the other treatments.