Introduction to Gunshot Injury Rehabilitation: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

# The projectile may exit the body, creating a bigger exit point, remain in the body or change direction, causing further damage<ref name=":2" /> | # The projectile may exit the body, creating a bigger exit point, remain in the body or change direction, causing further damage<ref name=":2" /> | ||

== Physical Impairments and Complications == | == Physical Impairments and Complications of Gunshot Injuries == | ||

[[File:Gunshot Injury Cross-Section.001.jpeg|thumb|<small>Gunshot Injury Cross-Section</small>]] | [[File:Gunshot Injury Cross-Section.001.jpeg|thumb|<small>Gunshot Injury Cross-Section</small>]]Gunshot wounds can cause various injuries, including diffuse soft tissue damage, muscle damage, nerve injury, vascular injury / haemorrhage, bone injury and severe pain.<ref name=":0">Moriscot A, Miyabara EH, Langeani B, Belli A, Egginton S, Bowen TS. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7997931/pdf/41536_2021_Article_127.pdf Firearms-related skeletal muscle trauma: pathophysiology and novel approaches for regeneration.] NPJ Regen Med. 2021 Mar 26;6(1):17.</ref> This injuries are discussed in detail below. | ||

Gunshot wounds can cause various injuries, including diffuse soft tissue damage, muscle damage, nerve injury, vascular injury / haemorrhage, bone injury and severe pain.<ref name=":0">Moriscot A, Miyabara EH, Langeani B, Belli A, Egginton S, Bowen TS. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7997931/pdf/41536_2021_Article_127.pdf Firearms-related skeletal muscle trauma: pathophysiology and novel approaches for regeneration.] NPJ Regen Med. 2021 Mar 26;6(1):17.</ref> This injuries are discussed in detail below. | |||

==== Diffuse soft-tissue damage ==== | ==== Diffuse soft-tissue damage ==== | ||

| Line 151: | Line 148: | ||

* Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) can be induced after traumatic events including a gunshot wound (GSW).<ref>Tieppo Francio V, Barndt B, Towery C, Allen T, Davani S. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6202970/pdf/bcr-2018-224702.pdf Complex regional pain syndrome type II arising from a gunshot wound (GSW) associated with infective endocarditis and aortic valve replacement.] BMJ Case Rep. 2018 Oct 16;2018:bcr2018224702.</ref> | * Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) can be induced after traumatic events including a gunshot wound (GSW).<ref>Tieppo Francio V, Barndt B, Towery C, Allen T, Davani S. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6202970/pdf/bcr-2018-224702.pdf Complex regional pain syndrome type II arising from a gunshot wound (GSW) associated with infective endocarditis and aortic valve replacement.] BMJ Case Rep. 2018 Oct 16;2018:bcr2018224702.</ref> | ||

=== Secondary Complications of | === Secondary Complications of Gunshot Injuries === | ||

The management of the secondary complications related to the gunshot injury is very complex. Early intervention and in-depth knowledge are required to maximise patients’ benefit from rehabilitation. | The management of the secondary complications related to the gunshot injury is very complex. Early intervention and in-depth knowledge are required to maximise patients’ benefit from rehabilitation. | ||

Revision as of 11:56, 23 April 2024

Original Editor - Zafer Altunbezel

Top Contributors - Ewa Jaraczewska, Jess Bell and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Gunshot injuries are high-energy injuries, which can cause significant tissue damage, paralysis or death. The severity of a gunshot injury depends on a number of factors. An in-depth understanding of the proper management of gunshot injury may help prevent secondary complications. Soft tissue injury, bone fracture, neural and vascular injury, or pain issues can be successfully managed at all levels of rehabilitation. This article offers information on the types of firearms, the injuries they can cause, and the impact gunshots can have on different body systems.

Definition of the Gunshot Injury[edit | edit source]

A gunshot injury is "the penetrating injury and its related consequences caused by a projectile from a firearm."[1]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The epidemiology of gunshot injuries is difficult to assess, and it varies based on the population, conflict set, country, characteristics of the conflict, and time it occurred:[1]

- in the USA in 2020, over 45,000 deaths were attributed to gun-related injuries[2] (i.e. 13.6 per 100,000 people[3])

- of the estimated 251,000 deaths caused by firearms in 2016, 50.5% of these deaths were in Guatemala, Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, Mexico and the USA[2][4]

- Wild et al. aimed to describe "conflict-related injuries sustained by civilians and local combatants in twenty-first century conflict".[5] They found that:[5]

- gunshot injuries caused 22% of injuries

- 42.2% of injuries occurred in urban settings

- 26.7% of injuries occurred in semi-urban settings

- 7.5% of injuries occurred in rural settings

- gunshot wounds are the second most common mechanism of injury among US military personnel during armed conflict[5]

Firearms and Gunshot Injuries[edit | edit source]

The wounding potential of a firearm depends on various factors, including:

- the type of the firearm (muzzle velocity)

- the type of bullet

- the larger the bullet, the slower its speed

- the distance to the target

- the size of the pellets

Based on the muzzle velocity, firearms can be divided into the low-velocity, medium-velocity, or high-velocity firearms.[1]

Low-Velocity Firearms[edit | edit source]

Low-velocity firearms, including small handguns and pistols, have a muzzle velocity of less than 1200 feet.[1] They tend to cause injuries that are similar to Gustilo-Anderson Type I and Type II injuries[6]

- Type I

- low energy

- wound size is less than one centimetre

- minimal soft tissue damage and fracture comminution

- wound is clean

- no neuromuscular injury

- Type II

- moderate energy

- wound size is between 1 and 10 centimetres

- moderate soft tissue damage and fracture comminution

- moderate wound contamination

- no neuromuscular injury

Medium-Velocity Firearms[edit | edit source]

Medium-velocity firearms, including high-calibre handguns and shotguns, have a muzzle velocity between 1200-2000 feet per second.[1] However, wound severity depends on various factors, including the distance and projectile:[1][7]

- shotguns are medium-velocity firearms, but because of the "large total mass of their lead pellets can increase their kinetic energy dramatically. [...] Depending on the distance to the target and the size of pellets, shotguns can reflect the wounding potential of high-velocity firearms or multiple low-velocity weapons. [...] Very close proximity of shotgun to the target (< 2 m) results in not only the pellet projection, but also shell fragments and wadding."[8]

High-Velocity Firearms[edit | edit source]

High-velocity firearms have a muzzle velocity greater than 2000 feet per second,[1] and they are associated with more substantial tissue damage.[7] They tend to cause Gustilo-Anderson Type III wounds. [6]

- Type III (A, B, or C)

- high energy

- wound size is usually greater than 10 centimetres

- extensive soft tissue damage

- severe fracture comminution

- extensive wound contamination

- periosteal stripping present

- may require flap coverage (III B and III C)

- exposed fracture with arterial damage that requires repair may be present (III C)

Mechanism of Gunshot Injury[edit | edit source]

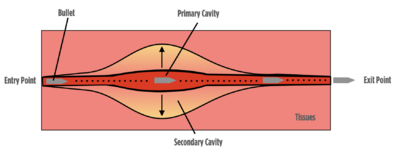

- The projectile hits the body and transfers its kinetic energy and heat to the tissues. This creates a permanent cavity, approximately the size of the projectile's cross-sectional area:[1]

- The projectile may exit the body, creating a bigger exit point, remain in the body or change direction, causing further damage[1]

Physical Impairments and Complications of Gunshot Injuries[edit | edit source]

Gunshot wounds can cause various injuries, including diffuse soft tissue damage, muscle damage, nerve injury, vascular injury / haemorrhage, bone injury and severe pain.[9] This injuries are discussed in detail below.

Diffuse soft-tissue damage[edit | edit source]

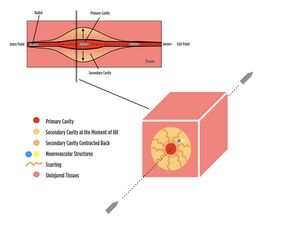

Soft tissue damage is caused by the permanent cavity or temporary cavitation.[9]

- tissues in the primary (permanent) cavity are injured by the projectile and extreme kinetic energy transfer[1]

- tissues in the temporary cavity are "destroyed by projectile compression and shearing that leaves a projectile trail"[9]

There may be partial or complete damage to the soft tissues, including ruptures, lacerations, internal burns and scarring in the later stages.[1] The following factors determine the extent of the wound depth and damaged area:

- projectile impact: velocity, mass, shape, calibre, material, yawing and impact distance:[9][1]

- Mass/shape: as projectile diameter / length increase, more damage is likely

- velocity: as the velocity increases, the amount of kinetic energy dramatically increases, causing more harm

- impact distance: as projectiles travel longer distances, they lose more of their kinetic energy and cause less harm, whereas even smaller projectiles from close distances can cause extensive damage

- Yaw is "the angle between the long axis of the bullet and its direction of flight."[10] As the distance increases, the projectile loses its stability and starts to yaw off. While this decreases the amount of kinetic energy transfer, it can increase the cross-sectional area, causing more damage[1]

- tissue impact: density, elasticity, and thickness[9]

- high elasticity and low density equal less damage[10]

- skin has a large amount of elasticity and relatively low density

- lungs have a much lower density and absorb less energy

- bones are dense and absorb more energy

- the entry and exit points and trajectory within the body[1]

- if they are close to the nervous plexus, more severe damage can occur

- if they are close to main arteries or veins, there may be more complicated clinical presentations

- projectile fragmentation

- more fragments = more than one trajectory within the body, causing more severe internal issues to manage in the following days and months[1]

Muscle Damage[edit | edit source]

"Skeletal muscle is suggested to be more sensitive to permanent cavitation, with temporary cavitation thought to induce less damage (unless the vasculature is disrupted) due to skeletal muscle’s inherent elasticity."[9]

Skeletal muscles can be affected by laceration, contusion or crush injury, denervation, haemorrhage, ischaemia, burns, and volumetric muscle loss. Primary trauma can be complicated by secondary trauma, including:[9]

- infection and sepsis as a result of contamination from the bullet or debris accumulated on clothing or the skin

- surgical debridement of damaged tissue

- excessive physical movement

Immobilisation and nutrient deficiency are considered common side effects leading to volumetric muscle loss.

Nerve Injury[edit | edit source]

Mechanisms of gunshot-related peripheral nerve injury include:[11]

- direct transection of the nerve

- indirect injury from thermal damage, shock waves, and laceration secondary to fracture fragment displacement

- compression due to swelling or subacute scar formation

The most frequently affected nerves in the upper extremities are the ulnar nerve and the brachial plexus.[11]

As a result of soft tissue cavitation, gunshot-related injuries can induce axonotmesis and neuropraxia.[12] Axonotmesis "describes the range of peripheral nerve injuries that are more severe than a minor insult, such as those resulting in neurapraxia, yet less severe than the transection of the nerve, as observed in neurotmesis."[13] Neuropraxia is the "focal segmental demyelination at the site of injury without disruption of axon continuity and its surrounding connective tissues."[14]

Vascular Injury / Haemorrhage[edit | edit source]

Vascular injury can lead to blood loss or haemorrhage. Haemorrhage can be internal or external. The most common sign of vascular injury is haematoma.

A haemorrhagic area can form around irreversibly damaged tissue following gunshot injury. This extra vacation zone "is characterized by interstitial bleeding but the absence of macroscopically evident tissue destruction."[15]

Bone Injury[edit | edit source]

- Drill-hole

- low-energy ballistic penetration

- affects metaphyseal region of long bones

- incomplete fracture, including remote spiral fractures, which may sometimes be caused by a fall on the femur after injury[16]

- limited extension of fracture lines

- Comminuted fractures

- high-energy ballistic penetration

- a secondary effect of cavitation associated with the fluid properties of bone marrow

- associated with a high incidence of secondary complications, including infection and nonunion[17]

- the rate of infection is higher in patients with a skin flap[17]

- the rate of nonunion is higher in patients who have vascular injuries[17]

Pain[edit | edit source]

- Peripheral nerve injury can cause neuropathic pain resulting from thermal injury, cavitation, and compression of the neural elements by fibrosis[18]

- Patients with gunshot wounds in a combat setting are at a 45% higher risk of developing chronic pain than injured civilians in the general population. [19]

- 70% of individuals with gunshot injuries develop chronic pain.[20]

- The rate of developing chronic pain increases with gunshot injuries sustained to a larger number of anatomical parts of the body.[19]

- Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) can be induced after traumatic events including a gunshot wound (GSW).[21]

Secondary Complications of Gunshot Injuries[edit | edit source]

The management of the secondary complications related to the gunshot injury is very complex. Early intervention and in-depth knowledge are required to maximise patients’ benefit from rehabilitation.

The following are the common secondary complications of gunshot injuries:[1]

- Joint contractures as a result of immobilisation after comminuted and complex open fractures requiring external fixation.

- Myofascial, chronic, or neuropathic pain due to internal scarring, internal burns, wound or bone infection.

- Peripheral nerve injuries due to heterogeneity and the conditions on the field, and presenting with sensory or motor dysfunctions that may require referral to a specialist.

- Deep vein thrombosis or different types of embolism

- Complex regional pain syndrome (Causalgia) known as military pain syndrome. It "tends to affect combat soldiers after they sustain wartime injuries from blasts and gunshots."[22]

- Central sensitisation

- Mental health disorders including post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety or depression tends to worsen overtime with long-term decline in mental health status.[23]

Skills and Knowledge Required to Treat Gunshot Injuries[edit | edit source]

It is recommended that rehabilitation professionals treating gunshot injuries have a solid understanding of the following topics:[1]

- Neuroanatomy

- To perform a neurological examination

- To plan the treatment

- To recognise signs and symptoms that warrant referral to speciality services

- Pain neuroscience

- To provide pain education to prevent the development of chronic pain

- Clinical reasoning

- To manage complex cases

- To participate in/lead a multidisciplinary team

- Manual skills

- To treat joint contractures, internal scarring, and neurogenic compromise

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 Altunbezel Z. Introduction to Gunshot Injury Rehabilitation Course. Plus, 2024.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Stewart S, Tunstall C, Stevenson T. Gunshot wounds in civilian practice: a review of epidemiology, pathophysiology and management. Orthopaedics and Trauma 2023; 37(4):216-221.

- ↑ Menezes JM, Batra K, Zhitny VP. A nationwide analysis of gunshot wounds of the head and neck: morbidity, mortality, and cost. J Craniofac Surg. 2023 Sep 1;34(6):1655-60.

- ↑ Global Burden of Disease 2016 Injury Collaborators; Naghavi M, Marczak LB, Kutz M, Shackelford KA, Arora M, et al. Global mortality from firearms, 1990-2016. JAMA. 2018 Aug 28;320(8):792-814.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Wild H, Stewart BT, LeBoa C, Stave CD, Wren SM. Epidemiology of Injuries Sustained by Civilians and Local Combatants in Contemporary Armed Conflict: An Appeal for a Shared Trauma Registry Among Humanitarian Actors. World J Surg. 2020 Jun;44(6):1863-1873.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Gustilo Classification. Available from https://www.orthobullets.com/trauma/1003/gustilo-classification [last access 14.04.2024]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Baum GR, Baum JT, Hayward D, MacKay BJ. Gunshot Wounds: Ballistics, Pathology, and Treatment Recommendations, with a Focus on Retained Bullets. Orthop Res Rev. 2022 Sep 5;14:293-317.

- ↑ Gugala Z, Lindsey RW. Classification of Gunshot Injuries in Civilians. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 2003;408():p 65-81.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Moriscot A, Miyabara EH, Langeani B, Belli A, Egginton S, Bowen TS. Firearms-related skeletal muscle trauma: pathophysiology and novel approaches for regeneration. NPJ Regen Med. 2021 Mar 26;6(1):17.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Gunshot Wounds: Management and Myths (2012). Available from https://www.reliasmedia.com/articles/76797-gunshot-wounds-management-and-myths [last access 16.04.2024]

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Shields LBE, Iyer VG, Zhang YP, Shields CB. Gunshot-related nerve injuries of the upper extremities: clinical, electromyographic, and ultrasound features in 22 patients. Front Neurol. 2024 Jan 11;14:1333763.

- ↑ Straszewski AJ, Schultz K, Dickherber JL, Dahm JS, Wolf JM, Strelzow JA. Gunshot-Related Upper Extremity Nerve Injuries at a Level 1 Trauma Center. J Hand Surg Am. 2022 Jan;47(1):88.e1-88.e6.

- ↑ Chaney B, Nadi M. Axonotmesis. 2023 Sep 4. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–.

- ↑ Biso GMNR, Munakomi S. Neuroanatomy, Neurapraxia. [Updated 2022 Oct 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557746/ [last access 16.04.2024]

- ↑ Stefanopoulos PK, Hadjigeorgiou GF, Filippakis K, Gyftokostas D. Gunshot wounds: A review of ballistics related to penetrating trauma. Journal of Acute Disease 2014;3(3):178-185.

- ↑ Smith HW, Wheatley KK Jr. Biomechanics of femur fractures secondary to gunshot wounds. J Trauma. 1984 Nov;24(11):970-7.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Yeganeh A, Amiri S, Otoukesh B, Moghtadaei M, Sarreshtedari S, Daneshmand S, Mohseni P. Characteristic Features and Outcomes of Open Gunshot Fractures of Long-bones with Gustilo Grade 3: A Retrospective Study. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2022 May;10(5):453-458.

- ↑ Henriques VM, Torrão FJL, Rosa LAN, Sanches GE, Guedes F. Surgery as an Effective Therapy for Ulnar Nerve Neuropathic Pain Caused by Gunshot Wounds: A Retrospective Case Series. World Neurosurg. 2023 May;173:e207-e217.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Kuchyn I, Horoshko V. Chronic pain in patients with gunshot wounds. BMC Anesthesiol. 2023 Feb 7;23(1):47.

- ↑ Horoshko V. Value of the number of injured anatomical parts of the body and surgeries for pain chronicity in patients with gunshot wounds and blast injuries. Emergency Medicine 2023;19(3):141–143.

- ↑ Tieppo Francio V, Barndt B, Towery C, Allen T, Davani S. Complex regional pain syndrome type II arising from a gunshot wound (GSW) associated with infective endocarditis and aortic valve replacement. BMJ Case Rep. 2018 Oct 16;2018:bcr2018224702.

- ↑ Nelson CN, Glauser G, Kessler RA, Jack MM. Causalgia: a military pain syndrome. Neurosurgical Focus 2022;53(3): E9.

- ↑ Greenspan AI, Kellermann AL. Physical and psychological outcomes 8 months after serious gunshot injury. J Trauma. 2002 Oct;53(4):709-16.