Gout

Original Editors - Maggie Kraemer from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Maggie Kraemer, Admin, Lucinda hampton, Shaimaa Eldib, Fitim Cami, Kim Jackson, Elaine Lonnemann, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Wendy Walker and WikiSysop

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Gout is a common causes of chronic inflammatory arthritis, characterized by monosodium urate (MSU) monohydrate crystals deposition in the tissues. Most patients with gout have other comorbidities. The prevalence of gout is higher among individuals with chronic diseases such as hypertension, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, obesity, congestive heart failure, and myocardial infarction .

Gout and pseudogout are the 2 most common crystal-induced arthropathies. They are debilitating illnesses in which pain and joint inflammation are caused by the formation of crystals within the joint space.[1] [2][3]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Typically occurs in those above 40 years. There is a strong male bias of 20:1, with this bias more pronounced in younger and middle-aged adults. In the elderly, the gender distribution is more equal. Rarely seen in children (< 10% of all cases)[1] [4]

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

Hyperuricemia is the leading cause of gout. People with higher serum urate levels are not only at an elevated risk for gout flare-ups but will also have more frequent flare-ups over time.

- Other factors implicated for gout and/or hyperuricemia: older age, male sex, obesity, a purine diet, alcohol, medications, comorbid diseases, and genetics. Offending medications include diuretics, low-dose aspirin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and cyclosporine. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have found several genes that are associated with gout.

- Dietary sources that can contribute to hyperuricemia and gout include consumption of animal food such as seafood (e,g., shrimp, lobster), organs (e.g., liver, and kidney), and red meat (pork, beef).

- Some drinks like alcohol, sweetened beverages, sodas, and high-fructose corn syrup may also contribute to this disease[2]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

There are four stages of gout, although diagnosis does not require the presence or occurrence of each stage. The four stages are:

- Asymptomatic hyperuricemia ( serum urate > 7mg/dl): is the phase of gout prior to the first attack, when serum urate levels are elevated but no symptoms are present. [4]

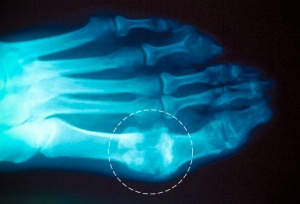

- Acute gouty arthritis: is the most often found (90%) at the first metatarsophalangeal joint. Symptoms generally begin with a sudden onset of localized, intense pain, often occurring at night. The pain may be great enough to awaken the patient. Redness, extreme tenderness, and swelling around the joint will occur within a few hours of the initial pain. Hypersensitivity, chills, tachycardia, malaise, and fever may also be present.[4] [5] [6] The skin may also become red or purplish, shiny, tense, and warm. [5]

Gouty arthritis is the most common clincial presentation:

Occasionally, acute gouty arthritis can also occur at the fingers, wrist, elbow, knee, ankle, and instep. Even more rarely, acute gouty arthritis may present at the cervical spine, sternoclavicular joint, shoulder, hip, and sacroilliac joint.[4] [5] [6] The initial attack may last a few days to 2 weeks, if left untreated [5] [6]. Attacks will recur; however time periods of months or years may elapse between them. As the attacks recur, they will become more intense and may spread to other joints in the body [4] [5] [6]. A patient may eventually experience several attacks per year [4] [5]

3. The intercritical phase: occurs after recovery from each episode. This phase is asymtomatic and may last for months to years at a time.It is important to note that although this is an aysmptomatic stage, serum urate levels are often still elevated and urate crystals may still be present. [4]

As the gout attacks continue, tophi will develop in the joints, tendons, bursae, subchondral bone, cartilage, ligaments, subcutaneous tissue, and synovium.[4] Tophi are hard nodules of sodium urate deposits that may vary in number and location.[4] [6] [5] Although typically a painless structure, the formation of tophi can cause an acute inflammatory response within the tissue. [6] [5] As the tophi become enlarged they may cause deformities, and there is potential for them to protrude through the skin and exude a white chalky substance (urate crystals). [4] [6] [5] Some of the most common sites of enlarged tophi are the forearm, ear, knee and foot. [4]

Note: Prior to the use of urate-lowering drugs for the treatment of acute gouty arthritis, tophi developed in approximately 30 - 50% of patients. [6]

4. Chronic tophaceous gout is characterized by increased pain, deformity (from tophi), decreased ROM, and subsequent functional loss.[4] [5] Due to the treatments used for gout today, chronic tophaceous gout is rare.

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Comorbidities with the patterns of gout treatment, the occurrence and the frequency of acute attacks. Cardiometabolic comorbidities, common in this patients' population, were associated with an increased risk of flares[7]

Management[edit | edit source]

The acute gout attacks are painful and potentially disabling, needing immediate treatment. The optimal therapy is towards controlling pain and inflammation.

Acutely, gout can be managed with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g. naproxen), colchicine, prednisolone, or newer cytokine blocking agents (e.g. IL-1 blockers such as anakinra or canakinumab) if refractory disease. In the long-term, xanthine oxidase inhibitors (e.g. allopurinol or febuxostat), uricosuric drugs (e.g. probenecid), or uricase agents (e.g. pegloticase) may be used to reduce urate levels and prevent further acute flares. Tophaceous gout can also be managed with surgical excision of symptomatic lesions.

Lifestyle modifications are also part of treatment.[7]

Medications

- NSAIDS ((selective/non-selective),Corticosteroids (oral or injections)[4] [5]: for pain and inflammation management during an acute attack[7].

- Allopurinol: to slow the rate of uric acid production and help prevent future attacks

- Cholchicine: occasionally used in the acute phase; however, use is less common due to frequency of side effects and narrow therapeutic range[5] [4]

- Supplementary analgesics

- Probenecid and sulfinpyrazone may be used to lower serum urate levels[5]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Synovial Fluid Analysis: Monosodium urate crystal identification remains the gold standard for gout diagnosis. Gout flare is marked by the presence of MSU crystals in synovial fluid obtained from affected joints of bursas visualized by direct examination of a fluid sample using compensated polarized light microscopy.

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

There are three main goals of the medical management of gout:

- Terminate acute attacks

- Prevent recurrence

- Correct and prevent further damage from hyperuricemia[4][5]

Termination of acute attacks - NSAIDs are the most common and generally effective treatment for acute attacks.[4][5] Cox-2 inhibitors are often the second choice for those who develop GI toxicity; however, they should be used with great caution with any patient with a history of CV complications or co-morbidities.[5] Intraarticular corticosteroid injection may also be effective for the management of an acute attack. Colchicine may also be used either po or by IV and may produce substantial pain relief if started immediately after onset of symptoms. Supplementary analgesics may also be recommended along with rest, elevation, and joint protection strategies. [4][5]

Prevention of recurrence - Daily low doses of NSAIDs or Colchicine are commonly used to prevent recurrent attacks.[5]

Correction and prevention of hyperuricemia - Uricosuric drugs or allopurinol may be used alone or in conjunction. Hypouricemic therapy may also be used for patients with tophi and a higher recurrence rate. Dietary restriction of high-purine foods is a less effective treatment technique but is still recommended. Carbohydrate restrictions may also be helpful. Other treatment possibilities include hydration greater than 3 litres per day. Alkalinization of urine, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, and surgical excision may also be beneficial.[5]

See here for a list of high-purine foods [8]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy management of gout falls under preferred practice pattern 4E: Impaired joint mobility, motor function, muscle performance, and range of motion associated with localized inflammation. [4]

The physical therapist should be aware that any patient with a history of gout, hyperuricemia, and/or a septic joint presentation should be referred for medical evaluation prior to treatment.[4]

During acute exacerbations the physical therapist should focus on reinforcement of management program and splinting, orthotics, or other assistive devices to protect the affected joint(s). [4]

A 2002 study in the Journal of Rheumatology found that the use of cryotherapy to alleviate the pain associated with acute bouts of gout may be effective. [9]

During intercritical phases physical therapists may offer assistance with maintenance of ROM, strength, and function. The physical therapist can also assist the patient in the creation of a suitable exercise routine and keeping their weight under control. [4][8]There is a Randomized Clinical Trial which suggests that Electroacupuncture in combination with blood letting puncture and cupping has relatively good results as a treatment for Gout. The treatment is effective mostly because the blood uric acid decreased significantly after the treatment was given to the patients. [10]

There is another study about Electroacupuncture combined with local blocking therapy on acute gouty arthritis that shows an improvement in health status of the patients. This treatment is positive and it also decreases blood uric acid levels. [11]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Pseudogout: is a form of arthritis that occurs 1/8th as often as gout. Symptoms are very similar to gout; however, the knee joint is primarily affected. Diagnosis is made by aspiration of synovial fluid.[6][12]

The difference between pseudogout and gout :

- Other differential diagnosis include: RA, neoplasm, septic arthritis, infectious arthritis, acute rheumatic fever, juvenile RA, acute fracture, and palindromic rheumatism. [4][5] Gouty arthritis typically presents with rapid development of severe joint pain, swelling, and tenderness that reaches its maximum within just 6-12 h, especially with overlying erythema, most classically in the first metatarsophalangeal joint. Demonstrating the presence of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in the joint fluid or tophus has been the gold standard for the diagnosis of gout. [13]

Case Reports[edit | edit source]

One case report that presents interesting implications for the physical therapist involves an elderly patient with lumbar spondylodiscal pathology secondary to her polyarticular gout. [14]

Interesting case report involving a middle aged man that developed symptoms of gout during a hospitalization. [15]

Case report of a patient whose tophi were limiting the FDS tendon. [16]

Case report involving presentation and differential diagnosis of acute monoarthritis. [17]

A series of case reports that examine some of the negative effects of Colchicine as a form of pharmacological management. [18]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Radiopedia Gout Available: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/gout(accessed 14.5.2022)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Fenando A, Widrich J. Gout (podagra).Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546606/ (accessed 14.5.2022)

- ↑ Joseph Kaplan, MD, MS, FACEP Attending Physician, Department of Emergency Medicine, Martin Army Community Hospital, Fort Benning, Georgia

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd ed. Saint Louis, MO: Saunders; 2009.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 Beers MH, et. al. eds. The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. 18th ed. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Research Laboratories; 2006.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 Goodman C, Snyder T. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier, 2007.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Primatesta P, Plana E, Rothenbacher D. Gout treatment and comorbidities: a retrospective cohort study in a large US managed care population. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2011 Dec;12(1):103.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Gout. National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. December 2006. http://www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Gout/default.asp. Accessed March 2010.

- ↑ Schlesinger N, Detry MA, Holland BK, Baker DG, Beutler AM, Rull M, Hoffman BI, Schumacher HR Jr. Local ice therapy during bouts of acute gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol 2002; 29(2): 331-334

- ↑ Zhao QW, Liu J, Qu XD, Li W, Wang S, Gao Y, Zhu LW.Department of Nutrition, Longnan Hospital, Daqing Oilfield General Hospital Group in Daqing City of Heilongjiang Province, Daqing 163453, China

- ↑ Liu B, Wang HM, Wang FY. The Forth Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin, Heilongjiang 150001, China

- ↑ Wheeless, C R. Pseudogout and Chondrocalcinosis. Wheeless' Textbook of Orthopaedics. November 2008. www.wheelessonline.com/image9/cppd2.jpg. Accessed March 2010.

- ↑ Schlesinger N. Department of Medicine, UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ 08903

- ↑ Lagier R, Gee W M. Spondylodiscal erosions due to gout: anatomicoradiological study of a case. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 1983 June; 42(3): 350-353.

- ↑ Dhoble A, Balakrishnan V, Smith R. Chronic tophaceous gout presenting as acute arthritis during an acute illness: a case report. Cases Journal. 2008; 1: 238.

- ↑ Sano K, et. al. Atypical Triggering at the Wrist due to Intratendinous Infiltration of Tophaceous Gout. Springer Hand. 2009 March; 4(1): 78-80.

- ↑ Ma L, Cranney A, and Holroyd-Leduc J. Acute monoarthritis: What is the cause of my patient's painful swollen joint. CMAJ. 2009 January; 180(1): 59-65.

- ↑ Morris I, Varughese G, and Mattingly P. Colchicine in acute gout. BMJ. 2003 November; 327(7426): 1275-1276.