Gastric Cancer: Difference between revisions

Corey Malone (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Kim Jackson (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (101 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | |||

'''Original Editors '''-Nick Goulooze & Corey Malone | '''Original Editors '''-Nick Goulooze & Corey Malone [[Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems|from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.]] | ||

''' | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Introduction == | |||

[[File:Stomach cancer patient.png|right|frameless|380x380px]] | |||

Gastric [[Oncology|cancer]] (also known as stomach cancer) is characterized by rapid or abnormal cell growth within the lining of the stomach, forming a tumor.<ref>The Free Dictionary. Stomach Cancer. http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/stomach+cancer (accessed 2 Feb 2013)</ref> | |||

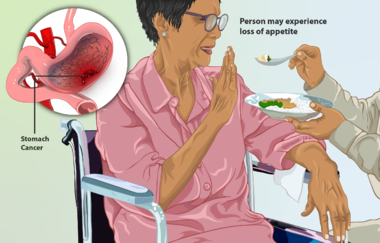

Image R - This is a depiction of a woman suffering from stomach cancer. Typically, a person may not experience any symptoms to begin with. However, as the condition progresses, one may exhibit symptoms, such as loss of appetite. A cross-section of the stomach with a tumour has been shown. | |||

* Gastric cancer is the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer and the third leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide. | |||

* In the United States, the incidence of gastric cancer has decreased during the past few decades although the incidence of gastroesophageal cancer has concomitantly increased. | |||

= | * There are two distinct types of gastric adenocarcinoma, intestinal (well-differentiated) and diffuse (undifferentiated), which have a distinct morphologic appearance, pathogenesis, and genetic profiles. | ||

* The only potentially curative treatment approach for patients with gastric cancer is surgical resection with adequate lymphadenectomy. | |||

* Current evidence supports perioperative therapies to improve a patient’s survival. | |||

* Regrettably, patients with an unresectable, locally advanced, or metastatic disease could solely be offered life-prolonging palliative therapy regimens<ref name=":0">Recio-Boiles A, Waheed A, Babiker HM. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459142/ Cancer, Gastric.] InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 May 18. StatPearls Publishing.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459142/ (last accessed 23.5.2020)</ref>. | |||

=== Types of Gastric Cancer === | |||

[[File:Stomach cancer illustration Wellcome L0014136.jpg|right|frameless]] | |||

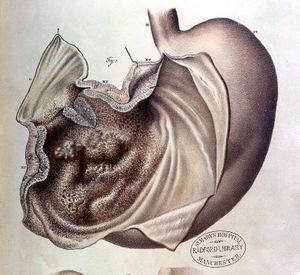

Different types of cells which make up the stomach. Therefore each particular cell has its own type of cancer. | |||

# <u>'''Adenocarcinoma'''</u> This is the most common type of gastric cancer (95% of gastric cancers<ref name="LivestrongCancerTypes">Livestrong. What are different types of gastric cancer. http://www.livestrong.com/article/102412-different-types-gastric-cancer/ (accessed Feb 13 2013)</ref>). This particular type of stomach cancer originates in the lining of the stomach, and effects the glandular cells of the stomach. It is believed that the majority of stomach cancer cases are caused by Heliobacter pylori bacteria.<ref name="LivestrongCancerTypes" /> | |||

# <u>'''Carcinoid'''</u> This type of stomach cancer effects the stomach's hormone producing cells. Carcinoid cells reproduce very slowly, and are incredibly rare. After the cancer has progressed a significant amount, a patient may have symptoms such as flushing of the face and chest, trouble breathing, and diarrhea. This is believed to be caused by hormones from the stomach.<ref name="LivestrongCancerTypes" /> | |||

# <u>'''Gastrointesinal Stromal Tumor'''</u> This type of stomach cancer originates in the nervous tissue surrounding the stomach, and is very rare.<ref name="LivestrongCancerTypes" /> | |||

# <u>'''Lymphoma'''</u> Rarely, cancer will spread from the lymphnodes within and around the stomach, causing gastric cancer.<ref name="LivestrongCancerTypes" /> | |||

As common with any type of cancer, gastric (stomach) cancer (see image R) can present in various stages, ranging from mild to severe. | |||

== Etiology == | |||

Research is still being conducted as to what actually causes stomach cancer. However, its has been shown to correlate with the following demographics and medical histories...<ref>Mayo clinic. Stomach cancer causes. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/stomach-cancer/DS00301/DSECTION=causes (accessed 2/13/13)</ref><ref>WebMD. Stomach cancer. http://www.webmd.com/cancer/stomach-gastric-cancer (Accessed 2/13/13)</ref> | |||

*Diets high in sodium | |||

*Men are two times more as risk than women | |||

*African-Americans and Asians are at greater risk | |||

*Blood group A | |||

*Middle age to elderly | |||

*Family history of stomach cancer | |||

*''Helicobacter pylori'' | |||

*Any other past medical history of gastrointestinal complications or surgery | |||

*Toxin exposure and smoking[[Image:H. Pylori.gif|right|frameless]] | |||

Most gastric cancers are sporadic, but 5% to 10% of cases have a family history of gastric cancer. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC), gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS), and familial intestinal gastric cancer (FIGC) are three major syndromes accounting up to 3% to 5% of hereditary familial gastric cancer. | |||

Stomach conditions can often times serve as precursors to cancer.eg, | |||

* ''atrophic gastritis'' - stomach glands have decreased and are inflamed | |||

* ''intenstinal metaplasia -'' cells within the lining of the intestine invade the stomach and take the place of stomach cells), | |||

* ''Helicobacter pylori'' infection - said to convert food particles into chemicals that cause mutations within the DNA of stomach cells, leading to cancer (consumption of foods high in antioxidants is said decrease the risk of stomach cancer by blocking the action of these chemicals on the stomach). <ref>Cancer. Stomach cancer causes, risk factors, and prevention topics. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/stomachcancer/detailedguide/stomach-cancer-what-causes (Accessed 2/14/14)</ref><ref>http://bioweb.uwlax.edu/bio203/s2008/pluym_evan/pictures/h_pylori%20scott%20smith.gif (accessed Feb 17 2013)</ref> | |||

== Epidemiology == | |||

* Gastric cancer rates are significantly declining worldwide. | |||

* In the United States, an estimated 28,000 new cases will be diagnosed with gastric cancer with an expected 10,960 new deaths during 2017<ref name=":0" /> | |||

== Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | |||

In the United States, most patients have symptoms of an advanced stage at the time of presentation. | |||

[[File:National-cancer-institute-0YBIMOqQzt0-unsplash.jpg|right|frameless]] | |||

Most common presenting symptoms for gastric cancers are: | |||

* Non-specific weight loss | |||

* Persistent abdominal pain | |||

* Dysphagia | |||

* Hematemesis, | |||

* Anorexia, nausea, early satiety, and dyspepsia. | |||

Patients presenting with a locally-advanced or metastatic disease usually present with significant abdominal pain, potential ascites, weight loss, fatigue, and have visceral metastasis on scans and can have a gastric-outlet obstruction. | |||

Common physical examination findings | |||

* Palpable abdominal mass indicating advanced disease | |||

* Signs of metastatic lymphatic spread distribution including Virchow’s node (left supraclavicular adenopathy), Sister Mary Joseph node (peri-umbilical nodule), and Irish node (left axillary node). Direct metastasis to peritoneum can present as Krukenberg’s tumor (ovary mass), Blumer’s shelf (cul-de-sac mass), ascites (peritoneal carcinomatosis), and hepatomegaly (often diffuse disease burden). | |||

Paraneoplastic manifestations may include dermatological (diffuse seborrheic keratosis or acanthosis nigricans), hematological (microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and hypercoagulable state [Trousseau’s syndrome]), renal (membranous nephropathy), and autoimmune (polyarteritis nodosa) are rare clinical findings and none is specific to gastric cancer.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

== Associated Co-morbidities == | |||

*A Study conducted by Heemskerk et al investigated associated co-morbidities upon history intake of 235 patients diagnosed with gastric cancer between 1992-2004. | |||

*138 of the 235 patient had at least one co-morbidity<ref>Vincent H., Fanneke L., Karel H., Anton H. Gastric carcinoma: review of the results of treatment in a community teaching hospital. World Journal of Surgical Oncology 2007; 5:81</ref> | |||

{| style="width: 345px; height: 235px;" cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="1" | |||

|+ | |||

|- | |||

| '''Co-morbidity''' | |||

| '''No. of Patients''' | |||

| '''%''' | |||

|- | |||

| Cardiovascular | |||

| 87 | |||

| 37 | |||

|- | |||

| Pulmonary | |||

| 24 | |||

| 10 | |||

|- | |||

| Diabetes | |||

| 19 | |||

| 8 | |||

|- | |||

| Other carcinoma | |||

| 20 | |||

| 9 | |||

|- | |||

| Previous GI surgery | |||

| 18 | |||

| 8 | |||

|- | |||

| BMI <u>></u> 30 | |||

| 12 | |||

| 5 | |||

|- | |||

| Clotting disorder | |||

| 2 | |||

| 1 | |||

|- | |||

| Other | |||

| 11 | |||

| 5 | |||

|} | |||

== Medications == | == Medications == | ||

There are many medications that are used for gastric cancer, each one prescribed by the patient's physician. Before a specific medication is prescribed to the patient, the physician should go through an extensive overview of the history of the patient, looking for history of allergic reactions to certain drugs. The patient should also be warned of adverse side effects that could effect the patient's everyday activities. | |||

== Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values == | == Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values == | ||

[[Image:Gastroscopy.gif|right|frameless]]All of the following tests are done in order to either to diagnose for gastric cancer or to determine what stage the cancer is in, in order to determine the best treatment approach for that patient. Following are a number of diagnostic and special tests. | |||

Tests and | * <u></u>Endoscopy<u><ref name="MayoClinicDxTests">Mayo Clinic. Stomach Cancer Tests and Diagnosis. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/stomach-cancer/DS00301/DSECTION=tests-and-diagnosis (accessed 2 Feb 2013)</ref></u> - This is a diagnostic procedure involving a thin tube with a camera inside of it that is passed through you esophagus into your stomach. Finds any suspicious tissue within stomach that should be tested for cancer. A biopsy can be done to determine if the suspicious tissue is malignant or benign.<u></u><ref>http://www.newcastlesurgery.com.au.php53-22.ord1-1.websitetestlink.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/gastroscopy.gif</ref> | ||

* Imaging<u><ref name="MayoClinicDxTests" /></u> | |||

** CT scan | |||

** PET | |||

** MRI | |||

* Exploratory Surgery<u><ref name="MayoClinicDxTests" /></u><br>This is performed should the doctor suspect your cancer has spread beyond just the stomach tissue. This procedure is done laparoscopically | |||

* <u></u>Physical Exam<u><ref name="WebMDDxTests">WebMD. How is Stomach Cancer Diagnosed. http://www.webmd.com/cancer/stomach-gastric-cancer?page=2 (accessed 2 Feb 2013)</ref></u><br>For enlarged lymph nodes, an enlarged liver, increased fluid in the abdomen (ascites), or abdominal lumps felt during a rectal exam. | |||

* Upper GI Series<u><ref name="WebMDDxTests" /></u><br>X-rays of the esophagus, stomach, and first part of the intestine taken after drink a barium solution. The barium outlines the stomach on the X-ray, which helps the doctor, using special imaging equipment, to find tumors or other abnormal areas | |||

http://www. | |||

Upper GI | |||

== Systemic Involvement == | == Systemic Involvement == | ||

=== Surgery Side Effects === | |||

The major surgery that patients with gastric cancer recieve is called a gastrectomy, which is where part or all of the patient's stomach is removed. When this happens, many changes will occur in the patient's diet because their body starts to process food differently. For instance, when the entire stomach is removed, the patient will not be able to absorb the vitamin B12<ref name="SideEffects">Cancer Compass. Stomach Cancer. http://www.cancercompass.com/stomach-cancer-information/side-effects.htm (accessed Feb 14 2013)</ref> If this happens, the patient will become anemic<ref name="VitB12">WebMD. Vitamin B12 Deficiency Anemia. http://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/vitamin-b12-deficiency-anemia-topic-overview (accessed Feb 14 2013)</ref>, and therefore must recieve injections of B12. The patient must also slowly resume a normal solid diet, starting with intravenous feeding and progressing to solids. Often times these patients also have cramps, nausea, diarrhea, and dizziness shortly after eating because food and liquid enter the small intestine too quickly<ref name="SideEffects" /> Finally, bile may back up from the small intestine to the esophagus or the part of the stomach that wasn't removed, and can cause stomach pain<ref name="SideEffects" />. | |||

Cancer | |||

The | |||

There | === Chemotherapy Side Effects === | ||

There are many side effects of chemotherapy that can be detrimental to a person's [[Quality of Life|quality of life]]. The reason being is because the role of chemotherapy is to kill any rapidly dividing cell, not just cancer cells. Therefore, patient's undergoing chemotherapy for gastric cancer can expect to lose there hair<ref name="SideEffects" />. They may also have oral problems such as sores and decreased taste buds<ref name="SideEffects" />. Since the digestive tract is also included in rapidly dividing cells, patients may also have digestive problems including stomach aches, nausea, vomiting and loss of appetite<ref name="SideEffects" />. Probably more importantly than all of this, though, the patient's immune system is often compromised due to the chemo's nature to kill off red and white blood cells<ref name="SideEffects" />. | |||

=== Radiation Side Effects === | |||

Radiaton has very similar side effects to chemotherapy. On top of this, it can cause patients to develop skin problems such as rashes and easier cuts<ref name="SideEffects" />. Patients can also expect to be extremely fatigued during their radiation treatment<ref name="SideEffects" />. | |||

== Medical Management == | |||

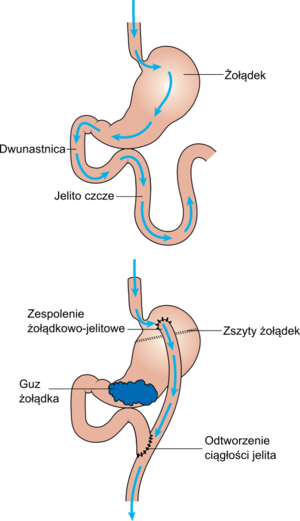

[[File:Stomach bypass surgery CRUK 108 pl.png|right|frameless]] | |||

Medical management of stomach cancer is dependent on its stage. | |||

Image R: Diagram showing before and after stomach bypass surgery | |||

* The most common form of intervention is surgery, mainly emphasizing removal or part or all of the stomach. | |||

* Radiation or chemotherapy may also be indicated should the cancer have metastisized to lymph nodes or other structures. | |||

Three common surgical interventions include endoscopic mucosal resection, subtotal (partial) gastrectomy, and total gastrectomy. | |||

# Endoscopic mucosal resection is indicated when the cancer has not spread beyond the inner lining of the stomach. The surgeon removes the cancerous cells via a long tube which travels down the esophagus and into the stomach. | |||

# A subtotal or partial gastrectomy is when only part of the stomach is removed. In this case, the cancer has spread significantly to the point in which it cannot be treated endoscopically. In addition, this procedure may involve the removal of a portion of the esophagus, small intestine, or nearby lymph nodes. | |||

# A total gastrectomy is when the cancer has invaded the entire stomach and it needs to be removed completely. Patients that have underwent a total gastrectomy must eat more often and in very small amounts. | |||

Palliative treatment is often times indicated for patients in the severe stages of gastric cancer (III and IV). The cancer has invaded the body to the point where a complete cure it is difficult. Palliative treatment aims to subside the effects of cancer as much as possible without actually curing it. For example, a stage III or IV tumor can put pressure against the esophagus, making it difficult to eat. A palliative treatment technique for this may involve the placement of a stent in the esophagus, or lazer beam therapy to vaporize that portion of the tumor.<ref>Cancer. Treatment choices by type and stage of stomach cancer. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/stomachcancer/detailedguide/stomach-cancer-treating-by-stage (Accessed 2/14/13)</ref><ref>Cancer. Surgery for stomach cancer. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/stomachcancer/overviewguide/stomach-cancer-overview-treating-surgery (Accessed 2/14/13)</ref> | |||

NB.Gastro-jejunostomy - a procedure in which an anastamosis is made with the stomach and the second part of the small intestine or jejunum via a small tube. Normal function of the outlet from the stomach into the first part of the small intestine (duodenum) is compromised due to the cancer. A gastro-jejunostomy is a form of palliative treatment to allow for proper transition of foods or medications from the stomach to the intestine.<ref>"Gastric Cancer; Report Summarizes Gastric Cancer Study Findings from Catholic University." Medical Devices & Surgical Technology Week (2013): 454. ProQuest Nursing & Allied Health Source. Web. 14 Feb. 2013.</ref> | |||

== Enhancing Outcomes Team Outcomes == | |||

The incidence of gastric cancer correlates with socioeconomic status and is clearly dependent on environmental/geographical factors. The management of gastric cancer patient requires the medical expertise of an interprofessional team in addition to a supportive team (nutritionist, social worker, nurses, geneticists, and palliative care providers). Members and patients should discuss the controversy surrounding the benefit of perioperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy alone or combined with competing standards of care and before choosing the best operation for gastric cancer and extension lymph node dissection<ref name=":0" />. | |||

== Physical Therapy Management == | |||

[[File:Strengthing exercise for old people .jpg|right|frameless]] | |||

Physical therapy should be utilized during cancer treatment to help a patient maintain function and to prevent the effects of bed rest. However, some people may choose not to go through PT because of fatigue or pain. After cancer treatment, though, patients can go to physical therapy to try and reverse some of the side effects of treatment, and to try and regain function that may have been lost after cancer treatment. | |||

* Lymphatic Therapy - Since [[Lymphoedema|lymphoedema]] can occur in conjunction with gastric cancer treatment, [[Lymphoedema|lymphatic]] drainage may be indicated. Since physical therapists are certified to perform lymphatic drainage, it is their responsibility to try and minimize the effects of lymphoedema<ref>Cancer Support Therapies. Manual Lymphatic Drainage Lymphoedema Cancer Related. http://cancersupporttherapies.com/therapies-available/lymphatic-drainage/ (accessed Feb 15 2013)</ref>. | |||

* Exercise - It is important for patients undergoing cancer treatment to stay active. Exercise during cancer treatment can help to minimize fatigue, improve a patient's immune system, reduce the effects of bed rest (such as contractures and muscle atrophy) and increase general quality of life. | |||

Some facilities may offer [[Cancer Rehabilitation and the Importance of Balance Training|Cancer Rehabilitation]] courses. | |||

http:// | |||

See also [[Physical Activity in Cancer]] and [[Breast Cancer]] | |||

== Case Reports/ Case Studies == | == Case Reports/ Case Studies == | ||

[[Gastric Cancer Case Studies|1) The Management Of Double Neoplasms: A Case Of A Patient With Small Cell Lung And Gastric Cancer Successfully Treated With Chemotherapy. By: Rossi, David, Alessandroni, Paolo, Fedeli, Stefano Luzi, Fedeli, Anna, Giordani, Paolo, Catalano, Vincenzo, Balzelli, Anna Maria, Casadei, V., Catalano, Giuseppina, Internet Journal of Oncology, 15288331, 2005, Vol. 3, Issue 1]]<br> | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | |||

<references /> | |||

[[Category: | [[Category:Oncology]] | ||

[[Category:Medical]] | |||

[[Category:Bellarmine_Student_Project]] | |||

[[Category:Conditions]] | |||

Latest revision as of 11:46, 8 August 2023

Original Editors -Nick Goulooze & Corey Malone from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Corey Malone, Nicholas Goulooze, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Kim Jackson, Elaine Lonnemann, Evan Thomas, WikiSysop, 127.0.0.1, Wendy Walker and Vidya Acharya

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Gastric cancer (also known as stomach cancer) is characterized by rapid or abnormal cell growth within the lining of the stomach, forming a tumor.[1] Image R - This is a depiction of a woman suffering from stomach cancer. Typically, a person may not experience any symptoms to begin with. However, as the condition progresses, one may exhibit symptoms, such as loss of appetite. A cross-section of the stomach with a tumour has been shown.

- Gastric cancer is the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer and the third leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide.

- In the United States, the incidence of gastric cancer has decreased during the past few decades although the incidence of gastroesophageal cancer has concomitantly increased.

- There are two distinct types of gastric adenocarcinoma, intestinal (well-differentiated) and diffuse (undifferentiated), which have a distinct morphologic appearance, pathogenesis, and genetic profiles.

- The only potentially curative treatment approach for patients with gastric cancer is surgical resection with adequate lymphadenectomy.

- Current evidence supports perioperative therapies to improve a patient’s survival.

- Regrettably, patients with an unresectable, locally advanced, or metastatic disease could solely be offered life-prolonging palliative therapy regimens[2].

Types of Gastric Cancer[edit | edit source]

Different types of cells which make up the stomach. Therefore each particular cell has its own type of cancer.

- Adenocarcinoma This is the most common type of gastric cancer (95% of gastric cancers[3]). This particular type of stomach cancer originates in the lining of the stomach, and effects the glandular cells of the stomach. It is believed that the majority of stomach cancer cases are caused by Heliobacter pylori bacteria.[3]

- Carcinoid This type of stomach cancer effects the stomach's hormone producing cells. Carcinoid cells reproduce very slowly, and are incredibly rare. After the cancer has progressed a significant amount, a patient may have symptoms such as flushing of the face and chest, trouble breathing, and diarrhea. This is believed to be caused by hormones from the stomach.[3]

- Gastrointesinal Stromal Tumor This type of stomach cancer originates in the nervous tissue surrounding the stomach, and is very rare.[3]

- Lymphoma Rarely, cancer will spread from the lymphnodes within and around the stomach, causing gastric cancer.[3]

As common with any type of cancer, gastric (stomach) cancer (see image R) can present in various stages, ranging from mild to severe.

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Research is still being conducted as to what actually causes stomach cancer. However, its has been shown to correlate with the following demographics and medical histories...[4][5]

- Diets high in sodium

- Men are two times more as risk than women

- African-Americans and Asians are at greater risk

- Blood group A

- Middle age to elderly

- Family history of stomach cancer

- Helicobacter pylori

- Any other past medical history of gastrointestinal complications or surgery

- Toxin exposure and smoking

Most gastric cancers are sporadic, but 5% to 10% of cases have a family history of gastric cancer. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC), gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS), and familial intestinal gastric cancer (FIGC) are three major syndromes accounting up to 3% to 5% of hereditary familial gastric cancer.

Stomach conditions can often times serve as precursors to cancer.eg,

- atrophic gastritis - stomach glands have decreased and are inflamed

- intenstinal metaplasia - cells within the lining of the intestine invade the stomach and take the place of stomach cells),

- Helicobacter pylori infection - said to convert food particles into chemicals that cause mutations within the DNA of stomach cells, leading to cancer (consumption of foods high in antioxidants is said decrease the risk of stomach cancer by blocking the action of these chemicals on the stomach). [6][7]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

- Gastric cancer rates are significantly declining worldwide.

- In the United States, an estimated 28,000 new cases will be diagnosed with gastric cancer with an expected 10,960 new deaths during 2017[2]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

In the United States, most patients have symptoms of an advanced stage at the time of presentation.

Most common presenting symptoms for gastric cancers are:

- Non-specific weight loss

- Persistent abdominal pain

- Dysphagia

- Hematemesis,

- Anorexia, nausea, early satiety, and dyspepsia.

Patients presenting with a locally-advanced or metastatic disease usually present with significant abdominal pain, potential ascites, weight loss, fatigue, and have visceral metastasis on scans and can have a gastric-outlet obstruction.

Common physical examination findings

- Palpable abdominal mass indicating advanced disease

- Signs of metastatic lymphatic spread distribution including Virchow’s node (left supraclavicular adenopathy), Sister Mary Joseph node (peri-umbilical nodule), and Irish node (left axillary node). Direct metastasis to peritoneum can present as Krukenberg’s tumor (ovary mass), Blumer’s shelf (cul-de-sac mass), ascites (peritoneal carcinomatosis), and hepatomegaly (often diffuse disease burden).

Paraneoplastic manifestations may include dermatological (diffuse seborrheic keratosis or acanthosis nigricans), hematological (microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and hypercoagulable state [Trousseau’s syndrome]), renal (membranous nephropathy), and autoimmune (polyarteritis nodosa) are rare clinical findings and none is specific to gastric cancer.[2]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

- A Study conducted by Heemskerk et al investigated associated co-morbidities upon history intake of 235 patients diagnosed with gastric cancer between 1992-2004.

- 138 of the 235 patient had at least one co-morbidity[8]

| Co-morbidity | No. of Patients | % |

| Cardiovascular | 87 | 37 |

| Pulmonary | 24 | 10 |

| Diabetes | 19 | 8 |

| Other carcinoma | 20 | 9 |

| Previous GI surgery | 18 | 8 |

| BMI > 30 | 12 | 5 |

| Clotting disorder | 2 | 1 |

| Other | 11 | 5 |

Medications[edit | edit source]

There are many medications that are used for gastric cancer, each one prescribed by the patient's physician. Before a specific medication is prescribed to the patient, the physician should go through an extensive overview of the history of the patient, looking for history of allergic reactions to certain drugs. The patient should also be warned of adverse side effects that could effect the patient's everyday activities.

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

All of the following tests are done in order to either to diagnose for gastric cancer or to determine what stage the cancer is in, in order to determine the best treatment approach for that patient. Following are a number of diagnostic and special tests.

- Endoscopy[9] - This is a diagnostic procedure involving a thin tube with a camera inside of it that is passed through you esophagus into your stomach. Finds any suspicious tissue within stomach that should be tested for cancer. A biopsy can be done to determine if the suspicious tissue is malignant or benign.[10]

- Imaging[9]

- CT scan

- PET

- MRI

- Exploratory Surgery[9]

This is performed should the doctor suspect your cancer has spread beyond just the stomach tissue. This procedure is done laparoscopically - Physical Exam[11]

For enlarged lymph nodes, an enlarged liver, increased fluid in the abdomen (ascites), or abdominal lumps felt during a rectal exam. - Upper GI Series[11]

X-rays of the esophagus, stomach, and first part of the intestine taken after drink a barium solution. The barium outlines the stomach on the X-ray, which helps the doctor, using special imaging equipment, to find tumors or other abnormal areas

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

Surgery Side Effects[edit | edit source]

The major surgery that patients with gastric cancer recieve is called a gastrectomy, which is where part or all of the patient's stomach is removed. When this happens, many changes will occur in the patient's diet because their body starts to process food differently. For instance, when the entire stomach is removed, the patient will not be able to absorb the vitamin B12[12] If this happens, the patient will become anemic[13], and therefore must recieve injections of B12. The patient must also slowly resume a normal solid diet, starting with intravenous feeding and progressing to solids. Often times these patients also have cramps, nausea, diarrhea, and dizziness shortly after eating because food and liquid enter the small intestine too quickly[12] Finally, bile may back up from the small intestine to the esophagus or the part of the stomach that wasn't removed, and can cause stomach pain[12].

Chemotherapy Side Effects[edit | edit source]

There are many side effects of chemotherapy that can be detrimental to a person's quality of life. The reason being is because the role of chemotherapy is to kill any rapidly dividing cell, not just cancer cells. Therefore, patient's undergoing chemotherapy for gastric cancer can expect to lose there hair[12]. They may also have oral problems such as sores and decreased taste buds[12]. Since the digestive tract is also included in rapidly dividing cells, patients may also have digestive problems including stomach aches, nausea, vomiting and loss of appetite[12]. Probably more importantly than all of this, though, the patient's immune system is often compromised due to the chemo's nature to kill off red and white blood cells[12].

Radiation Side Effects[edit | edit source]

Radiaton has very similar side effects to chemotherapy. On top of this, it can cause patients to develop skin problems such as rashes and easier cuts[12]. Patients can also expect to be extremely fatigued during their radiation treatment[12].

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Medical management of stomach cancer is dependent on its stage.

Image R: Diagram showing before and after stomach bypass surgery

- The most common form of intervention is surgery, mainly emphasizing removal or part or all of the stomach.

- Radiation or chemotherapy may also be indicated should the cancer have metastisized to lymph nodes or other structures.

Three common surgical interventions include endoscopic mucosal resection, subtotal (partial) gastrectomy, and total gastrectomy.

- Endoscopic mucosal resection is indicated when the cancer has not spread beyond the inner lining of the stomach. The surgeon removes the cancerous cells via a long tube which travels down the esophagus and into the stomach.

- A subtotal or partial gastrectomy is when only part of the stomach is removed. In this case, the cancer has spread significantly to the point in which it cannot be treated endoscopically. In addition, this procedure may involve the removal of a portion of the esophagus, small intestine, or nearby lymph nodes.

- A total gastrectomy is when the cancer has invaded the entire stomach and it needs to be removed completely. Patients that have underwent a total gastrectomy must eat more often and in very small amounts.

Palliative treatment is often times indicated for patients in the severe stages of gastric cancer (III and IV). The cancer has invaded the body to the point where a complete cure it is difficult. Palliative treatment aims to subside the effects of cancer as much as possible without actually curing it. For example, a stage III or IV tumor can put pressure against the esophagus, making it difficult to eat. A palliative treatment technique for this may involve the placement of a stent in the esophagus, or lazer beam therapy to vaporize that portion of the tumor.[14][15]

NB.Gastro-jejunostomy - a procedure in which an anastamosis is made with the stomach and the second part of the small intestine or jejunum via a small tube. Normal function of the outlet from the stomach into the first part of the small intestine (duodenum) is compromised due to the cancer. A gastro-jejunostomy is a form of palliative treatment to allow for proper transition of foods or medications from the stomach to the intestine.[16]

Enhancing Outcomes Team Outcomes[edit | edit source]

The incidence of gastric cancer correlates with socioeconomic status and is clearly dependent on environmental/geographical factors. The management of gastric cancer patient requires the medical expertise of an interprofessional team in addition to a supportive team (nutritionist, social worker, nurses, geneticists, and palliative care providers). Members and patients should discuss the controversy surrounding the benefit of perioperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy alone or combined with competing standards of care and before choosing the best operation for gastric cancer and extension lymph node dissection[2].

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy should be utilized during cancer treatment to help a patient maintain function and to prevent the effects of bed rest. However, some people may choose not to go through PT because of fatigue or pain. After cancer treatment, though, patients can go to physical therapy to try and reverse some of the side effects of treatment, and to try and regain function that may have been lost after cancer treatment.

- Lymphatic Therapy - Since lymphoedema can occur in conjunction with gastric cancer treatment, lymphatic drainage may be indicated. Since physical therapists are certified to perform lymphatic drainage, it is their responsibility to try and minimize the effects of lymphoedema[17].

- Exercise - It is important for patients undergoing cancer treatment to stay active. Exercise during cancer treatment can help to minimize fatigue, improve a patient's immune system, reduce the effects of bed rest (such as contractures and muscle atrophy) and increase general quality of life.

Some facilities may offer Cancer Rehabilitation courses.

See also Physical Activity in Cancer and Breast Cancer

Case Reports/ Case Studies[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ The Free Dictionary. Stomach Cancer. http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/stomach+cancer (accessed 2 Feb 2013)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Recio-Boiles A, Waheed A, Babiker HM. Cancer, Gastric. InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 May 18. StatPearls Publishing.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459142/ (last accessed 23.5.2020)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Livestrong. What are different types of gastric cancer. http://www.livestrong.com/article/102412-different-types-gastric-cancer/ (accessed Feb 13 2013)

- ↑ Mayo clinic. Stomach cancer causes. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/stomach-cancer/DS00301/DSECTION=causes (accessed 2/13/13)

- ↑ WebMD. Stomach cancer. http://www.webmd.com/cancer/stomach-gastric-cancer (Accessed 2/13/13)

- ↑ Cancer. Stomach cancer causes, risk factors, and prevention topics. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/stomachcancer/detailedguide/stomach-cancer-what-causes (Accessed 2/14/14)

- ↑ http://bioweb.uwlax.edu/bio203/s2008/pluym_evan/pictures/h_pylori%20scott%20smith.gif (accessed Feb 17 2013)

- ↑ Vincent H., Fanneke L., Karel H., Anton H. Gastric carcinoma: review of the results of treatment in a community teaching hospital. World Journal of Surgical Oncology 2007; 5:81

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Mayo Clinic. Stomach Cancer Tests and Diagnosis. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/stomach-cancer/DS00301/DSECTION=tests-and-diagnosis (accessed 2 Feb 2013)

- ↑ http://www.newcastlesurgery.com.au.php53-22.ord1-1.websitetestlink.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/gastroscopy.gif

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 WebMD. How is Stomach Cancer Diagnosed. http://www.webmd.com/cancer/stomach-gastric-cancer?page=2 (accessed 2 Feb 2013)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 Cancer Compass. Stomach Cancer. http://www.cancercompass.com/stomach-cancer-information/side-effects.htm (accessed Feb 14 2013)

- ↑ WebMD. Vitamin B12 Deficiency Anemia. http://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/vitamin-b12-deficiency-anemia-topic-overview (accessed Feb 14 2013)

- ↑ Cancer. Treatment choices by type and stage of stomach cancer. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/stomachcancer/detailedguide/stomach-cancer-treating-by-stage (Accessed 2/14/13)

- ↑ Cancer. Surgery for stomach cancer. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/stomachcancer/overviewguide/stomach-cancer-overview-treating-surgery (Accessed 2/14/13)

- ↑ "Gastric Cancer; Report Summarizes Gastric Cancer Study Findings from Catholic University." Medical Devices & Surgical Technology Week (2013): 454. ProQuest Nursing & Allied Health Source. Web. 14 Feb. 2013.

- ↑ Cancer Support Therapies. Manual Lymphatic Drainage Lymphoedema Cancer Related. http://cancersupporttherapies.com/therapies-available/lymphatic-drainage/ (accessed Feb 15 2013)