Functional Neurological Disorder: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 158: | Line 158: | ||

== Case Reports/ Case Studies<br> == | == Case Reports/ Case Studies<br> == | ||

Conversion Disorder Case Study | [[Conversion Disorder Case Study|Conversion Disorder Case Study]] | ||

{{pdf|Conversion motor paralysis overview and rehabilitation.pdf|Conversion Motor Paralysis Disorder: Overview and Rehabilitation Model}} | {{pdf|Conversion motor paralysis overview and rehabilitation.pdf|Conversion Motor Paralysis Disorder: Overview and Rehabilitation Model}} | ||

Revision as of 17:36, 20 January 2015

Original Editors - Abby Naville and Alex Piedmonte from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Alexandria Piedmonte, Jessica Hetzer, Abby Naville, Melissa Borst, Elaine Lonnemann, Naomi O'Reilly, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Kim Jackson, Wendy Walker, Adam Vallely Farrell, Mason Trauger, Evan Thomas, WikiSysop, Vidya Acharya and 127.0.0.1

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Conversion disorder is a rare psychodynamic occurrence that consists if the physical expression of an unconscious conflict or stress in a person’s life. [1] This physical expression is characterized by the presentation of signs and symptoms that are inconsistent or cannot be explained by known anatomy or physiology.[2]

Patients that fall under this presentation, however, should not be confused with malingerers or categorized as someone feigning an illness. This population is not intentionally simulating symptoms but is genuinely experiencing them. Symptom presentation consists of the patient’s conception of a particular disease process therefore their presentation will not follow typical or expected patterns, such as dermatome or myotome changes. The physical therapist should carefully document these changes in order to recognize indescrepencies. [1][2]

Conversion disorder is also known as “hysterical neurosis” , “conversion type”, or “functional neurological symptom disorder”. It falls under the classification of 'somatic symptom disorder' according to the DSM V, a change from the DSM IV which included a large cluster of disorders known as somatoform disorders that are also recognized under this new heading. [3][2][4]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

The prevalence of conversion disorder varies depending on the population being studied and whether or not conversion symptoms are reported. It is estimated that the prevalence ranges from 0.01% to 0.5% of the general population.[2] Additionally, 20-25% of patients in a general hospital setting experience symptoms of conversion while only 5% of patients are diagnosed with conversion disorder. In a neurological setting the prevalence increases. A study found that 14% of 100 consecutive patients admitted to a neurological ward did not have objective evidence of neurological disease. Conversion disorder is more commonly seen in women with the age of onset that spread across the lifespan.[5] The ratio of females to males ranges from 2:1 up to 10:1.[2]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation [6][7][8][2][edit | edit source]

The onset of conversion symptoms usually occurs abruptly during adolescence or early adulthood, often following a stressful life event. Symptoms often appear neurologic encompassing sensory and/or motor presentations. Generally, patients present with one symptom at any given time and the severity of symptoms may vary under certain circumstances. Often symptoms will be present within an exam but are absent during functional movement or reflex reactions. The most common symptoms include:

• Anesthesia

• Paralysis

• Ataxia

• Tremor

• Tonic-clonic pseudoseizures

• Deafness

• Blindness

• Aphonia

• Globus hystericus

• Parkinsonism

• Syncope

• Coma

• Anosmia

• Nystagmus

• Convergence spasm

• Facial weakness

• Ageusia

Prognosis is best for patients that have acute onset of symptoms or have symptoms immediately following an acute stressor. These patients stand the best chance of recovery and will do so in a matter of a few weeks. Symptoms of tremor or seizure are more persistent while aphoina, blindness, and paralysis tend to improve. A minority of patients experience symptoms chronically, but is usually correlated with an associated personality disorder.

Associated Co-morbidities[5][9][edit | edit source]

Co-morbidities can be key in determining whether or not a patient is experiencing conversion symptoms or conversion disorder. Conversion disorder is commonly associated with psychiatric conditions or emotional distress. A study found that 47.7% of the subjects with conversion disorder experienced some type of dissociative disorder.[9] The most common psychiatric conditions seen in those with conversion disorder include:

• Undifferentiated Somatoform Disorder

• Generalized Anxiety Disorder

• Dysthymia

• Simple Phobia

• Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

• Major Depression

• Borderline Personality Disorder

• Childhood emotional/sexual abuse

• Physical Neglect

• Self-mutilated behavior

• Suicide attempts

Medications[edit | edit source]

Conversion disorder can be improved by the use of drugs to treat underlying issues such as stress, anxiety, or other psychological conditions. This may include any antidepressant, anti-anxiety medications or other medications depending on a patient’s profile. [10]

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

Conversion Disorder is diagnosed based on clinical presentation of signs and symptoms. It should be considered when signs and symptoms are atypical for a specific condition. The following criteria from the DSM-IV can be used to diagnose conversion disorder[2]:

| Table 1. DSM-IV Diagnostic Criteria for Conversion Disorder (300.11) |

| A. One or more symptoms or deficits affecting voluntary motor or sensory function suggestion neurological or other general medical condition. |

| B. Psychological factors are judged to be associated to the symptom or deficit because conflicts or other stressors precede initiation or exacerbation of the symptom or deficit. |

| C. The patient is not feigning or intentionally producing his or her symptoms or deficits. |

| D. The symptom or deficit cannot, after appropriate investigation, be fully explained by a general medical condition, by the direct effects of a substance, or as a culterally sanctioned behavior or experience. |

| E. The symptom is not limited to pain or to a disturbance in sexual functioning and is not better explained by another mental disorder. |

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, Text Revision. American Psychiatric Association, 2000. |

There is emerging literature on structural imaging and functional MRI’s of the brain in people with conversion disorder. Studies have shown that those with conversion disorder tend to have reduced volumes of right and left basal ganglia and right thalamus compared to others without conversion disorder. When looking at a functional MRI of a person with unilateral sensory loss in the hand, thought to be from conversion disorder, activation in the contralateral somatosensory region appeared when the uninvolved hand was stimulated. When the involved hand was stimulated, there was no such activation. This is important for future diagnostic criteria; however, functional MRI technology is still highly experimental when looking at conversion disorder.[5]

Etiology/Causes[edit | edit source]

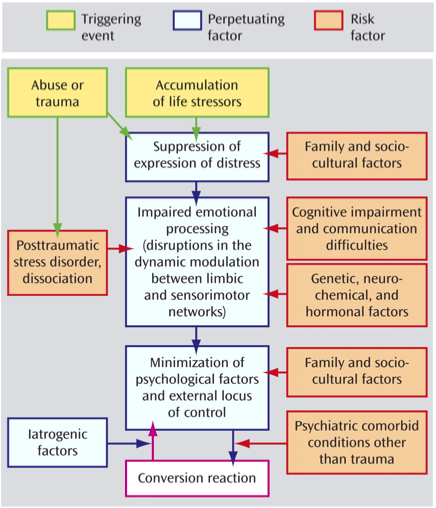

Conversion disorder is largely attributed to psychological conflicts or stressors. A patient displaying conversion symptoms is channeling their distress into physical expression, which is usually followed by a reduction in a patient’s anxiety. Thus, most theories about why conversion disorder manifests are based on Freundian concepts of suppression and avoidance as an unconscious defense mechanism against traumatic events.[11] [12] Often, symptoms are a reflection of a medical condition that a patient has witnessed in another or that they have experienced previously. However, this disorder is not premeditated and it is thought that the symptoms may be a sign or symbolic representation of emotions that the patient is unable to express in words.[2]

The translation of emotional stress into conversion symptoms is recognized as the primary gain of the disorder, where the conflict is limited to the unconscious thus leading to reduction in the patient’s anxiety. Whereas external benefits, such as avoiding obligations or receiving attention from loved ones, are defined as secondary gain. If not addressed these can become perpetuating triggers that create a barrier to remission of conversion symptoms. [11][12][2]

The pathophysiology of conversion disorder is not well understood and is not the current basis for treatment. However, functional imaging of the brain suggests that neural circuits connecting will power, movement, and perception are disrupted in conversion disorder. These studies are limited by small numbers of participants and varying study designs thus there have been no substantial conclusions.[13]

Systemic Involvement [4][edit | edit source]

Since individuals with Conversion disorder display signs and symptoms of diseases or impairments that they have seen or experienced then numerous systems may be involved dependin on the illness their presenting with. Possible systems affected are listed below.

Cardiac:

•Shortness of breath

•Palpitations

•Chest pain

Gastrointestinal:

•Vomiting

•Abdominal pain

•Difficulty swallowing

•Nausea

•Bloating

•Diarrhoea

Musculoskeletal:

•Pain in the legs or arms

•Back pain

•Joint pain

Neurological:

•Headaches

•Dizziness

•Amnesia

•Vision changes

•Paralysis or muscle weakness

Urogenital:

•Pain during urination

•Low libido

•Dyspareunia

•Impotence

•Dysmenorrhoea, irregular menstruation and menorrhagia

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

After diagnois is made, a phyciatrist will proceed to inform the patient that neither examination or diagnostic tests have shown any damage to their neurologic system. The patient is then educated that even though the direct cause of their symptoms is not known it is common for similar patient's to recover in a matter of a few weeks.[2] Some treatment options depending on how the patient presents and their past medical history are listed below.

- Seeing a counselor or a psychologist can help treat conversion symptoms and prevent them from coming back

- Especially helpful with patients that have comorbid psychological conditions such as anxiety and depression

- Family therapy may be indicated if there are triggering factors

- Graded exposure to avoided situations

- Problem solving techniques

- Reframing of beliefs about their illness

Pharmacotherapy[13]

- Usually used for treatment of underlying conditions

- Lack of controlled trials

- Some small studies reportreduction in conversion symptoms with use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, beta-blockers, analgesics, benzodiazepines, and antidepressants

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation[10][13]

- Uses weak electrical currents to alter the brain's biochemistry

- Success reducing conversion symptoms related to Posttraumatic distress disorder

Physical Therapy[2]

- Help prevent secondary complications from conversion disorder

- Certain cases show that physical therapy sessions expedite the process of remission

- See section on Physical Therapy Management

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence) [5][14][15][edit | edit source]

Conversion disorder can present in many different ways. It typically presents mimicking a neurological disorder with parasthesia and anesthesia. Research has shown that physical therapy has shown to be an effective method of treatment for patients with conversion disorder.

During an initial evaluation of a patient, a thorough history should be taken to rule out any organic neurological, orthopedic, or cardiovascular condition. Any new stressors in ones life should be noted along with any psychological distress and history of abuse. Objective measures should be taken to validate the patient’s beliefs that they have a condition that is causing their impairments. However, after the initial evaluation these conversion symptoms should be ignored to prevent reinforcement of behaviors.

Once conversion disorder is confirmed, the therapist should develop good rapport with this patient as they are currently experiencing psychological stress. Depending on how the patient presents, physical therapists should treat the impairments as they would if the patient had a neurological condition with an organic cause. It has been shown that progressing exercises from simple tasks to more challenging ones has been effective in those with neurological disorders and is no different in those with conversion disorder. The therapist should progress the motor skill and provide less verbal and tactile cueing along with less assistance.

Due to the psychological component of conversion disorder, behavioral modification should be incorporated into the treatment sessions in physical therapy. A patient with conversion often assumes the role of a “sick person.” When people recognize their “illness” this reinforces their behavior. In a physical therapy session, when these unwanted behaviors (ataxia, loss of balance, and paralysis) occur, the therapist should ignore these behaviors by not commenting on the impairments and only giving positive feedback when the patient performs well (normal movements, strength, and gait). The therapist should educate the family members and other interdisciplinary team members on the behavioral component to lead to a better recovery for the patient.

Alternative/Holistic Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

- Neuroimaging supports that conversion symptoms and hypnosis use common neurologic pathways

- Some studies show hynosis as a useful adjuct treatment, but is not essential for improving symptoms

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Organic background: Thorough examination must be done to rule out any condition of organic nature that may present in the same way as the conversion. General diagnosis that could potentially present this way include: myasthenia gravis, idiopathic dystonias, and multiple sclerosis.[14]

Psychological Background: There are two types of psychological conditions that may present with signs and symptoms of conversion disorder; voluntary and involuntary.

Voluntary

• Factitious disorder: Physical and mental symptoms voluntarily produced by a patient for the motive to take on the role of a patient. They typically present with exaggerated symptoms, great knowledge of medical terminology, and numerous previous hospitalizations.[14][5]

• Malingering: Physical and mental symptoms voluntarily produced by a patient for the motive of a secondary gain (vacation, released from jail, compensation, etc). This differs from factitious disorder because the patient does not have any psychological need to take on the patient role; this is simply for a personal gain. [14][5]

Involuntary

• Involuntary psychological conditions can present like conversion disorder and are often co-morbidities to conversion disorder include: anxiety, depression, borderline personality disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and dissociative disorder.[14]

Case Reports/ Case Studies

[edit | edit source]

Conversion Disorder Case Study

Conversion Motor Paralysis Disorder: Overview and Rehabilitation Model

Conversion Disorder Presenting With Neurologic and Respiratory Symptoms

Physical Therapy Management for Conversion Disorder: Case Series

Resources

[edit | edit source]

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1HuCGFZSJIJ9pX2PVInlYeLL38JnLSjV86nPfiSzi5FJmcqY_c|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Goodman C, Fuller K. Chapter 3: Pain Types and Viscerogenic Pain Patterns. In:Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral. 5th Edition. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier; 2013:144-145

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

- ↑ Conversion Disorder: Definition. Mayo Clinic Website. http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/conversion-disorder/basics/definition/con-20029533. Accessed on March 14,2014

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Patient.co.uk Somatic Symptom Disorder. Patient.co.uk website.http://www.patient.co.uk/doctor/somatic-symptom-disorder. Accessed on March 20,2014.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Feinstein A. Conversion disorder: advances in our understanding. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal [serial online]. May 17, 2011;183(8):915-920. Available from: Academic Search Premier, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 14, 2014.

- ↑ Conversion Disorder: Symptoms. Mayo Clinic Website. http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/conversion-disorder/basics/symptoms/con-20029533. Accessed on March 14, 2014

- ↑ Roffman J, Stern T. Conversion disorder presenting with neurologic and respiratory symptoms. Primary Care Companion To The Journal Of Clinical Psychiatry [serial online]. 2005;7(6):304-306. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 14, 2014.

- ↑ Mace C, Trimble M. Ten-year prognosis of conversion disorder. The British Journal Of Psychiatry: The Journal Of Mental Science [serial online]. September 1996;169(3):282-288. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 14, 2014.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Sar V, Akyüz G, Kundakçi T, Kiziltan E, Dogan O. Childhood trauma, dissociation, and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with conversion disorder. The American Journal Of Psychiatry [serial online]. December 2004;161(12):2271-2276. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 14, 2014.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Conversion Disorder: Treatments and Drugs. Mayo Clinic Website. http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/conversion-disorder/basics/treatment/con-20029533. Accessed on March 14, 2014

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Heruti R, Levy A, Adunski A, Ohry A. Conversion motor paralysis disorder: overview and rehabilitation model. Spinal Cord. July 2002;40(7):327-334. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 14, 2014.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Feinstein A. Conversion disorder: advances in our understanding. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal De L'association Medicale Canadienne. May 17, 2011;183(8):915-920. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 14, 2014

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Cynthia M. Stonnington, M.D.; John J. Barry, M.D.; Robert S. Fisher, M.D., Ph.D. Conversion disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry. September 01, 2006; 163(9):1510-1517. http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/article.aspx?articleID=96982&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;resultClick=1. Accessed March 14, 2014.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Heruti R, Levy A, Adunski A, Ohry A. Conversion motor paralysis disorder: overview and rehabilitation model. Spinal Cord. July 2002;40(7):327-334. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 20, 2014.

- ↑ Ness D. Physical therapy management for conversion disorder: case series. Journal Of Neurologic Physical Therapy: JNPT. March 2007;31(1):30-39. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 19, 2014.