Fecal Incontinence

- Specifically, Fecal Incontinence associated with pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum

Definition[edit | edit source]

The International Continence Society provides the following definitions of bowel incontinence:[1]

- Fecal incontinence (FI) is defined as the involuntary loss of feces (liquid or solid). FI is also referred to as accidental bowel leakage.

- Anal incontinence (AI) is defined as the involuntary loss of feces and/or flatus.

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Fecal incontinence (FI) and anal incontinence (AI) affect all age groups of both men and women, including pregnant and postpartum women, and have a significant impact on quality of life.

During Pregnancy:

During the late stages of pregnancy, physiological changes such as, increased transit time leading to altered stool consistency and increased intra-abdominal pressure, may contribute changes in incontinence for women with preexisting pelvic floor or anal sphincter dysfunction.

Childbirth:

During childbirth, pelvic floor muscle and/or nerve injury may lead to incontinence. Injury of the neural innervation to the pelvic floor muscles can lead to the inability to use these muscles adequately. Damage to the pudendal nerve can occur through can become stretched and compressed, with demyelination and subsequent denervation, due to the by the passage of the fetal head through the pelvis.[2][3] Anal sphincter laceration can lead to FI, however, not all anal sphincter injuries result in FI.[4] Additionally, the use of instruments (ie. forceps or vacuum) during vaginal delivery can increase the risk or FI or AI, particularly if an obstetric anal sphincter injury occurred.[5][6][7] When comparing the use of forceps versus vacuum during vaginal delivery, one study found the use of forceps significantly increased the risk of FI.[8] There remains controversy in the literature with regards to the effect of vaginal delivery versus cesarean birth and its affect on FI or AI.[9][10]

Post-Partum:

Incontinence symptoms are more common during the postpartum period than during pregnancy.[11] Additionally, women who experienced symptoms of incontinence during pregnancy were more likely to experience these symptoms in postpartum.[12]

Other Risk Factors for developing FI:[13][14][15]

- Older age

- Diarrhea

- Fecal urgency

- Urinary incontinence

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hormone therapy

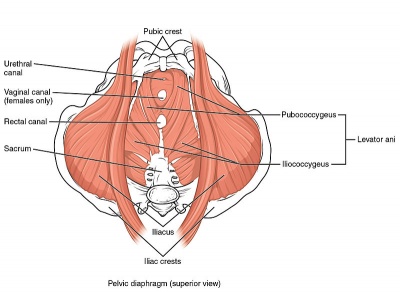

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Please see the page "Pelvic Floor Anatomy," for further details regarding anatomy.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Symptoms:[16]

- unable to stop the urge to defecate, which comes on so suddenly, patient may comment that that they don't make it to the toilet in time

- May state that they have additional bowel issues, such as, diarrhea, constipation, gas and bloating

Objective:

Physical examination – The physical examination should include pelvic examination, inspection of the perianal area, and a digital rectal examination (DRE).

- Pelvic Examination: assess the health of the vaginal tissue, pelvic organ prolapse (supine and standing), and the ability to contract and relax the pelvic floor muscles

- Perianal Examination: assess for area for dermatitis, fistula, prolapsing hemorrhoids, or rectal prolapse, as well as the anocutaneous reflex

- DRE: assess the anal resting tone and the ability to contract and relax the pelvic floor muscles

Management/Interventions[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapist

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) is recommended for women during pregnancy and beginning at four to six weeks postpartum. PFMT has been proven to be effective in improving the contractility and strength of the pelvic floor muscles during pregnancy and in postpartum.[17][18] The studies cited here are examining the effects of the PFMT on urinary symptoms, it is reasonable to conclude that it may beneficial for FI/AI because the puborectalis muscle contributes to anal continence and is strengthened during PFMT. In order to gain benefits from PFMT, it is imperative that patients perform a pelvic floor muscle contraction (ie. Kegel) correctly. Physiotherapist can help patients to how to perform a correct pelvic floor muscle contraction through, verbally cueing (ie. think about holding in gas), visually assessing the pelvic floor region to ensure proper contraction, tactile feedback through a DRE while a pelvic floor muscle contraction is being performed by the patient, and biofeedback (ie. electromyography to assess the pelvic floor muscles).

Physician

- Educated patients about PFMT and the points listed in "Education and Diet."

- Fiber-bulking agent may be suggested to improve stool consistency.[19]

Imaging:

- Endoanal ultrasound: to detect functional and structural abnormalities (eg, anal sphincter injury), if a significant sphincter injury is already present it may allow women to make an informed choice regarding mode of delivery.[20]

Education and Diet:

- Keep a food and symptom diary to help identify factors that cause diarrhea and incontinence

- Avoiding foods or activities known to worsen symptoms

- Avoidance of incompletely digested sugars (ie. eg, fructose, lactose, FODMAPs), and caffiene

- Low FODMAPs diet[21]

- Improving perianal skin hygiene

Other:

- Anal inserts: may be an option for patients who have exhausted other treatment options listed

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ The International Continence Society. Glossary. Available from: https://www.ics.org/glossary?q=fecal%20incontinence

- ↑ Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN. Pudendal nerve damage during labour: prospective study before and after childbirth. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 1994 Jan 1;101(1):22-8.

- ↑ Allen RE, Hosker GL, Smith AR, Warrell DW. Pelvic floor damage and childbirth: a neurophysiological study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 1990 Sep;97(9):770-9.

- ↑ Oberwalder M, Connor J, Wexner SD. Meta‐analysis to determine the incidence of obstetric anal sphincter damage. British journal of surgery. 2003 Nov;90(11):1333-7.

- ↑ Larsson C, Hedberg CL, Lundgren E, Söderström L, TunÓn K, Nordin P. Anal incontinence after caesarean and vaginal delivery in Sweden: a national population-based study. The Lancet. 2019 Mar 23;393(10177):1233-9.

- ↑ Pretlove SJ, Thompson PJ, Toozs‐Hobson PM, Radley S, Khan KS. Does the mode of delivery predispose women to anal incontinence in the first year postpartum? A comparative systematic review. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2008 Mar 1;115(4):421-34.

- ↑ Blomquist JL, Muñoz A, Carroll M, Handa VL. Association of Delivery Mode With Pelvic Floor Disorders After Childbirth. Jama. 2018 Dec 18;320(23):2438-47.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick M, Behan M, O'Connell PR, O'Herlihy C. Randomised clinical trial to assess anal sphincter function following forceps or vacuum assisted vaginal delivery. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics & gynaecology. 2003 Apr 1;110(4):424-9.

- ↑ Larsson C, Hedberg CL, Lundgren E, Söderström L, TunÓn K, Nordin P. Anal incontinence after caesarean and vaginal delivery in Sweden: a national population-based study. The Lancet. 2019 Mar 23;393(10177):1233-9.

- ↑ Blomquist JL, Muñoz A, Carroll M, Handa VL. Association of Delivery Mode With Pelvic Floor Disorders After Childbirth. Jama. 2018 Dec 18;320(23):2438-47.

- ↑ Brown SJ, Gartland D, Donath S, MacArthur C. Fecal incontinence during the first 12 months postpartum: complex causal pathways and implications for clinical practice. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2012 Feb 1;119(2):240-9.

- ↑ Gartland D, MacArthur C, Woolhouse H, McDonald E, Brown SJ. Frequency, severity and risk factors for urinary and faecal incontinence at 4 years postpartum: a prospective cohort. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2016 Jun;123(7):1203-11.

- ↑ Ng KS, Sivakumaran Y, Nassar N, Gladman MA. Fecal incontinence: community prevalence and associated factors—a systematic review. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2015 Dec 1;58(12):1194-209.

- ↑ Halland M, Koloski NA, Jones M, Byles J, Chiarelli P, Forder P, Talley NJ. Prevalence correlates and impact of fecal incontinence among older women. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2013 Sep 1;56(9):1080-6.

- ↑ Staller K, Townsend MK, Khalili H, Mehta R, Grodstein F, Whitehead WE, Matthews CA, Kuo B, Chan AT. Menopausal hormone therapy is associated with increased risk of fecal incontinence in women after menopause. Gastroenterology. 2017 Jun 1;152(8):1915-21.

- ↑ Mayo Clinic. Fecal Incontinence. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/fecal-incontinence/symptoms-causes/syc-20351397

- ↑ Mørkved S, Bø K, Schei B, Salvesen KÅ. Pelvic floor muscle training during pregnancy to prevent urinary incontinence: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2003 Feb 1;101(2):313-9.

- ↑ Marques J, Botelho S, Pereira LC, Lanza AH, Amorim CF, Palma P, Riccetto C. Pelvic floor muscle training program increases muscular contractility during first pregnancy and postpartum: electromyographic study. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2013 Sep;32(7):998-1003.

- ↑ Bliss DZ, Savik K, Jung HJ, Whitebird R, Lowry A, Sheng X. Dietary fiber supplementation for fecal incontinence: a randomized clinical trial. Research in nursing & health. 2014 Oct;37(5):367-78.

- ↑ Jordan, P.A., Naidu, M., Sultan, A.H. and Thakar, R., 2015, June. Effect of subsequent vaginal delivery on bowel symptoms and anorectal function in women who sustained a previous obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI). In INTERNATIONAL UROGYNECOLOGY JOURNAL(Vol. 26, pp. S45-S46). 236 GRAYS INN RD, 6TH FLOOR, LONDON WC1X 8HL, ENGLAND: SPRINGER LONDON LTD.

- ↑ Shepherd SJ, Lomer MC, Gibson PR. Short-chain carbohydrates and functional gastrointestinal disorders. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2013 May;108(5):707.