Fahr's Syndrome

Original Editor - Sarah Dorsey, Maria Tyumkin, Megan Willerth, Jennifer Withers, Logan Wood.

Lead Editors

This is an in-progress page created by and for the students in the School of Rehabilitation Therapy at Queen's University in Ontario, Canada. Please do not edit unless you are involved in this project, but please come back in the near future to check out new information!![edit | edit source]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

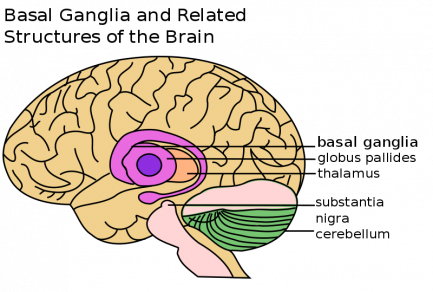

Definition: Fahr’s syndrome is also known as Fahr’s disease, familial idiopathic basal ganglia calcification and primary familial brain calcification. It is a rare neurological disorder characterized by bilateral (and often symmetrical) calcifications of the areas in the brain including:

- basal ganglia (most commonly the globus pallidus)

- cerebellum (most commonly the dentate nucleus)

- thalamus

- hippocampus

- cerebral cortex

Calcifications are hypothesized to be due to lipid deposition and demyelination. The presentation of an individual with Fahr’s disease can vary greatly with some remaining asymptomatic despite receiving imaging confirmation of calcification. In more severe cases individuals will present first and most prominently with extrapyramidal symptoms.

Further symptoms may include: progressive psychosis, cognitive impairment, dementia, gait disturbance, and sensory changes. Fahr’s syndrome can present at age, but is typically first diagnosed in individuals between 40-60 years old.

Pathological Process/Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Etiology: Fahr's syndrome is familial and inherited, with autosomal dominant cases making up 60% of diagnoses. Some research has shown that fewer cases may be inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion. There are also several other factors that could lead to brain calcification which include: endocrinopathies, vasculitis, mitochondrial disorders, infections, other inherited disorders, radiation, chemotherapy and carbon monoxide poisoning.

Prognosis: The prognosis of Fahr’s syndrome differs from person to person and thus is hard to predict. Fahr’s syndrome is a progressive disease with no known cure and no specific treatments at this time. Due to Fahr’s progressive and degenerative features individuals will often lose previously acquired skills and motor control, which can lead to death. There is no direct correlation between the amount of calcium deposits that are seen in the brain and the degree of neurological impairments displayed by an individual with the disease.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Lesions in the basal ganglia can cause patients to present with different motor deficits. These include slowness of movement, involuntary extra movement and alterations in posture and muscle tone. Therefore patients with basal ganglia involvement can present on a continuum of motor behaviour from severely limited as seen in the final stages of Parkinson’s disease to excessive movements apparent in Huntington’s disease. In “Fahr’s Disease Registry”, the most common symptoms were movement disorders, in particular parkinsonism, which affects more than half of patients[1].

Neuropsychiatric Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Associated Movement Disorders[edit | edit source]

| Associated Movement Disorders | |

|---|---|

| Dystonia | a movement disorder that causes sustained muscle contractions, abnormal postures and repetitive twisting movements that can vary in speed[2]. Dystonia can affect one or several regions of the body[3]. There is presently no cure for dystonia, but the goal is to help decrease the severity of muscle spasms, pain and awkward postures to improve overall quality of life[4]. |

| Athetosis | an involuntary movement disorder characterised by slow, smooth, sinuous, writhing movements, also described as “wormlike movements”. More common in the distal upper extremities, also prevalent in other areas of the body such as face, trunk, neck and tongue[5]. Pure Athetosis is uncommon, usually presents with a combination of spasticity, tonic spasms, or chorea. |

| Chorea | described as abnormal movement involving involuntary, irregular, purposeless, non-rhythmic, abrupt, rapid and unsustained, that can flow from one area of the body to another. These movements can vary in amplitude, small movements of the fingers to flailing of limb movements, referred to as ballism[6]. Patients are at an increased falls risk due to impairments in balance, strength and increased fatigue. Musculoskeletal and respiratory changes can result in physical deconditioning and contribute to decreased participation in daily activities and social participation[7]. |

| Spasticity | motor disorder characterized by a velocity dependent increase in muscle tone with increased resistance to stretch, the larger and quicker the stretch, the stronger the resistance of the spastic muscle. During the rapid movement, a sudden inhibition or letting go of the limb termed the “clasp knife” response may follow initial high resistance. Chronic spasticity is associated with contracture, abnormal posturing and deformity, muscle weakness, functional limitations and disability[8]. |

| Tremor | is an involuntary shaking movement. It can be seen in the extremities, usually as a resting tremor seen when a patient is at rest, or in the head and trunk when the patient is trying to hold an upright posture. A resting tremor can eventually progress to an action tremor, which is tremor with movement. Although the pathophysiology is slightly different, Parkinson’s patients tend to exhibit a mild tremor first on only one side of the body; there is not enough data to decisively say if this it true for Fahr’s patients. Tremors tend to worsen with stress, anxiety or an excited emotional state. Particularly in later stages, tremors interfere with the ability to perform fine motor tasks such as picking up or holding objects. |

| Rigidity | is an increased resistance to passive movement that is not affected by speed or amplitude of motion. There are two types: lead pipe - which is constant throughout range - and cogwheel - which is jerky with tension felt intermittently throughout a movement. Rigidity affects a patient’s ability to move and therefore independently carry out activities of daily living (ADLs). In many patients, rigidity can be increased by stress or active movements. |

| Hypomimia | is the reduced ability to portray facial expressions, both automatic and voluntary, that is often seen in Parksinon’s and Fahr’s patients. This frozen, masked expression is often incorrectly interpreted by others as depression, coldness, apathy and reduced cognition[9]. This can cause difficulty in communication and relationships, including patient-therapist relationships; studies have shown that practitioners - including physiotherapists - tend to view patients with facial masking as more depressed, less sociable and less cognitively competent[9]. Therefore it is an important component of the treatment of Fahr’s disease to not allow oneself to form negative preconceptions about a client based on a symptom they cannot control. |

| Gait | is affected by Fare’s disease similar to Parkinson’s disease. Fare’s patients can exhibit unsteadiness, clumsiness, a shuffling gait, or freezing of gait[10]. Gait abnormalities can be exacerbated by other symptoms such as tremor or rigidity. |

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

| Diagnostic criteria |

|---|

| 1. Genetic abnormality and family history inheritance of autosomal dominant trait or autosomal recessive trait |

| 2. Bilateral calcification in Basal Ganglia visible on neuroimaging |

| 3. Exclude secondary causes of Fahr syndrome and biochemical abnormalities (infection, traumatic injury, metabolic, toxic) |

| 4. Progressive neurological dysfunction involving movement and psychiatric disorders |

Neuroimaging

- CT scan used to assess the location and severity of cerebral calcification

- Common areas for calcification deposits include the basal ganglia, caudate, lentiform nuclei, thalamus, globus pallidus, pontine vascular white matter, and periventricular matter

- MRI - can be used to locate calcification in the brain, but appearance varies depending on stage of disease and the amount of calcification

- Skull radiography may be used to locate symmetrical calcium clusters lateral to midline. Subcortical and cerebellar calcifications will appear wavy.

Tests

- Proband can be used as a diagnostic tool of PFBC. Prior to performing genetic testing. Secondary causes of basal ganglia calcification must be ruled out. As well as, a hereditary autosomal dominant trait must be present. A SLC20A2 genetic sequence is analyzed for deletion.duplication first. If no mutation is found PDGFRB genetic sequence is analyzed. If no mutation is found, other genetic diseases may be associated with calcium deposits.

- Urine and blood analysis are performed to assess calcium metabolism and presence of heavy metals in the body.

- Cerebrospinal fluid analysis are used to analyze an infectious or autoimmune cause of PFBC

Neurological exam

- Jerky ocular pursuit also known as saccadic intrusion. As the patient follows a target such as a pen the eyes jerk as they move.

- The patient may present with generalized chorea of the limbs and or face. This may be due to the calcification deposits in basal ganglia.

- Patient may present with ataxic gait. As the disease progresses the patient may develop dystonic posture of BL feet due to repetitive contractions while walking. Also, the patient may develop twitching of their eyes and face.

Other assessments

Screen for Psychosis and depression - PHQ 9 depression scale

Family history - neurological issues

Gait assessment - ongoing/ progressive unsteady/disturbed gait, and falls

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

add links to outcome measures here (see Outcome Measures Database)

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Treatment is symptomatic. Parkinson-like symptoms are non-responsive to Levodopa. Risperidone can be helpful for psychiatric symptoms and antidepressants are used for mood disorder symptoms. No known studies on whether dementia medications are helpful.

If the calcifications are idiopathic treatment is focused on symptoms, if the cause of the calcifications is known treatment aimed at underlying illness or condition (https://radiopaedia.org/articles/fahr-syndrome-1).

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to the differential diagnosis of this condition

Physiotherapy Intervention[edit | edit source]

When creating an effective treatment plan it is important to consider: (insert image)

Treatment Note

There is no cure or standard treatment plan for Fahr’s syndrome. Symptoms and disease presentation are treated on an individual basis. (NINDS fahr's syndrome information page). In addition, due to the lack of literature on Fahr’s disease and the similarity of symptoms with Parkinson’s, Huntington’s and other neurological conditions, therapists should use their clinical judgement in combination with evidence about the treatment of the overlapping symptoms in similar populations. Recommendations for treatment include a focus on function, participation and exercise capacity, as well as preventing or slowing the progression of secondary impairments such as muscle weakness(O’sullivan rehabilitation text).

| Treatment Goals May Include |

|---|

| 1. Increase and/or maintain range of motion, prevent contractures |

| 2. Strengthen weakened muscles that may be underutilized |

| 3. Improvement and maintenance of postural stability in static postures and during mobility |

| 4. Gait retraining and/or falls prevention |

| 5. Symptom management |

- Maintaining Range of Motion and Flexibility

- Range of motion exercises, passive stretching and facilitated stretching can help maintain tissue extensibility and physical functioning. Stretching can be combined with joint mobilization

- Note for patients with spasticity, therapist should use constant pressure over bony prominences and avoid direct pressure on spastic muscles. Limb movement out of spastic position should be slow, repeated motions

- Serial casts may be used for patients at risk of contractures and deformity

- Note for patients with dystonia, braces may be helpful in preventing contractures. However, they tend to be poorly tolerated and are only really used for writer’s cramp to enable the hand to be used more effectively and comfortably

- Strengthening Underutilized Muscles

- A general conditioning program is beneficial for most patients with neurological disorders to maintain strength and function.

- Include the principles of overload, specificity, cross training and reversibility in designing a program. Note with specificity, it is best to attempt to create exercises that will carry over into the client’s daily life, for example following an isometric protocol will not guarantee effects carry over to improved dynamic performance which is more applicable to ADLs.

- Muscles that commonly become weak in neurological populations include antigravity extensor muscles.

- In older patients, it is generally recommended to start at a lower intensity, aiming for sets of 10-12 repetitions.

- Exercise machines, in contrast to free weights, may be safer for patients with more progressed motor symptoms since movements are more controlled.

- Improving Postural Instability

- Instruct patient in correct sitting posture, using appropriate vertical cuing such as lines on the wall, and the clinician exhibiting appropriate upright posture

- Patients with basal ganglia dysfunction are recommended to practice maintenance of postural control in a variety of tasks and environments and incorporate activities that require anticipatory responses

- Progress activities from wide to narrow base of support, static to dynamic, low to higher levels of cognition – single vs. dual task, also increasing degrees of freedom available

- Patients with basal ganglia dysfunction are encouraged to incorporate task specific balance training, specifically during functional activities such as transfers, reaching, and using stairs

- Gait retraining/Falls Prevention

- For patients with basal ganglia dysfunction, auditory cueing may assist with step timing, for example counting, stepping to a metronome or music. In particular, common strategies to improve Parkinsonian symptoms such as the regularity of gait and gait freezing, include visual cues like lasers attached to a walker or cane. Individual studies have also shown that participation in other activities, such as dance and high-speed cycling, can potentially improve gait.

- Provision of assistive devices when appropriate to improve function

- Educate patient on safety awareness, including how to get up after a fall and decreasing clutter in their living space

- Assessment for orthotic device may be required (for example ankle dystonia)

- For hyperkinetic disorders, protective gear such as helmets, pads may be required if at high risk for falls

- Symptom Management

- Relaxation techniques, such as deep breathing, are beneficial because patients with neurological conditions such as Fahr’s disease tend to experience a lot of stress and anxiety. Relaxation has documented benefits including elevated energy levels and a greater perception of control.

- For hyperkinetic disorders, deep brain stimulation. Which involves a surgically implanted device that sends electrical impulses to the brain to help control movement

- Soft tissue release is beneficial for patients experiencing dystonia and spasticity. Case studies have also shown benefits of massage for Parkinson’s symptoms, including gait, range of motion, pain and upper limb function.

- Sensory stimulation for patients with basal ganglia dysfunction.

- Note that for patients living with dystonia, many will develop sensory tricks on their own that help to improve dystonic posture, for example touching specific parts of the face. The benefits of these tricks are transient in nature and may have less effect during the later stages of the disease

- There is some evidence that whole body vibration (WBV) may improve gait, tremor, rigidity, proprioception and balance in patients with neurological diseases, including Parkinson’s. However, systematic reviews have concluded that more high-quality research is needed

Resources for Patients[edit | edit source]

add appropriate resources here

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Calabro R, Spadaro L, Marra A, Bramanti P. Fahr's disease presenting with dementia at onset: a case report and literature review. Behav Neurol 2014;2014,750975. doi:10.1155/2014/750975

- ↑ Velickovic M, Benabou R, Brin MF. Cervical dystonia: pathophysiology and treatment options. Drugs 2001;61(13),1921-1943. doi:10.2165/00003495-200161130-00004

- ↑ Bressman SB. Dystonia genotypes, phenotypes, and classification. Adv in Neurol. 2004;94,101-107. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14509661 (accessed 1 May 2018).

- ↑ The Dystonia Society. Generalized dystonia. https://www.dystonia.org.uk/generalised-dystonia (accessed 1 May 2018).

- ↑ Haines DE, Ard MD. Fundamental neuroscience: for basic and clinical applications. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2006. p413.

- ↑ Micheli FE, LeWitt PA, SpringerLink (Online service). Chorea: causes and management. London: Springer London; 2014. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-1-4471-6455-5.pdf (accessed 1 May, 2018)

- ↑ European Huntington’s Disease Network. 2013. Physiotherapy clinical guidelines for Huntington’s disease. https://www.huntingtonsociety.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/EHDN-Physio-Guide1.pdf (accessed 3 May 2018).

- ↑ O’Dwyer NJ, Ada L, Neilson PD. Spasticity and muscle contracture following stroke. Brain 1996;119:1737-1749. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/df70/aa84ee19dc6daed946a1de2d8ff26ed744fd.pdf (accessed 1 May 2018).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Tickle-Degnen L, Zebrowitz LA, Ma H. Culture, gender and health care stigma: practitioners' response to facial masking experienced by people with Parkinson's disease. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:95-102. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.008

- ↑ Stamelou M, Kojovic M, Edwards MJ, Bhatia KP. Ability to cycle despite severe freezing of gait in atypical parkinsonism in Fahr's syndrome. Movement Disorders. 2011;26:2141-2142. doi:10.1002/mds.23794