Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

== Diagnostic Procedures == | == Diagnostic Procedures == | ||

Although the DSM-5 criterion describe 4 required characteristics for an accurate diagnosis, a comprehensive medical history, interview, relevant questionnaires, clinical examination and motor tests are all important steps in identifying a child with DCD, and it is recommended that this diagnosis is not provided until the age of 6 years. <ref name=":2" /> In most countries, a physician must diagnose DCD, however, parents, educational professsionals and physical therapists, are often the first to recognize atypical motor behavior and deficient skills at home or in the school setting, where it becomes more obvious.<ref>Biotteau M, Danna J, Baudou É, Puyjarinet F, Velay JL, Albaret JM, Chaix Y. Developmental coordination disorder and dysgraphia: signs and symptoms, diagnosis, and rehabilitation. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment. 2019;15:1873.</ref><ref name=":2" /> | Although the DSM-5 criterion describe 4 required characteristics for an accurate diagnosis, a comprehensive medical history, interview, relevant questionnaires, clinical examination and motor tests are all important steps in identifying a child with DCD, and it is recommended that this diagnosis is not provided until the age of 6 years. <ref name=":2" /> In most countries, a physician must diagnose DCD, however, parents, educational professsionals and physical therapists, are often the first to recognize atypical motor behavior and deficient skills at home or in the school setting, where it becomes more obvious.<ref>Biotteau M, Danna J, Baudou É, Puyjarinet F, Velay JL, Albaret JM, Chaix Y. Developmental coordination disorder and dysgraphia: signs and symptoms, diagnosis, and rehabilitation. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment. 2019;15:1873.</ref><ref name=":2" /> Differential diagnosis is an important component of the medical evaluation, as neurological disorders associated with clumsiness and lack of motor coordination must be ruled out, including Friedreich's ataxia, cerebral palsy, myopathies, and traumatic brain injury. <ref name=":2" />In addition to an interview of the child and caregiver, the DCDQ (Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire) has demonstrated valid and reliable psychometric properties to assist in identifying children with DCD and is available at no cost at [https://www.dcdq.ca www.dcdq.ca]. <ref>Wilson BN, Crawford SG, Green D, Roberts G, Aylott A, Kaplan BJ. Psychometric properties of the revised developmental coordination disorder questionnaire. Physical & occupational therapy in pediatrics. 2009 Jan 1;29(2):182-202.</ref><ref>Wilson BN, Kaplan BJ, Crawford SG, Roberts G. The developmental coordination disorder questionnaire 2007 (DCDQ’07). Administrative manual for the DCDQ107 with psychometric properties. 2007 Oct:267-72.</ref> After administration of this tool, based on the child’s age and total score, a physical therapist can determine whether the child may have DCD or is not likely to be affected.<ref>Harris SR, Mickelson EC, Zwicker JG. Diagnosis and management of developmental coordination disorder. Cmaj. 2015 Jun 16;187(9):659-65.</ref> In order to assess the DCD criteria of a child with a suspected diagnosis, physical therapists use clinical observation, as well as appropriate outcome measures to identify and assess motor skills, such as the Movement Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd edition (MABC-2), which is considered the gold standard for children ages 3-16 years with a suspected diagnosis of DCD. <ref name=":2" /><ref>Henderson SE, Sugden DA, Barnett AL, editors. Movement assessment battery for children - second edition [MABC-2], 2nd ed. London, The Psychological Corporation, 2007.</ref> | ||

== Outcome Measures == | == Outcome Measures == | ||

Revision as of 00:23, 24 April 2022

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Developmental coordination disorder (DCD) is a neuromotor disorder affecting approximately 5-6% of school-aged children. [1] In order to be accurately diagnosed with DCD, a child must demonstrate motor coordination difficulties that significantly interfere with activities of daily living or academic achievement. [1] According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition (DSM-5), [2] the diagnostic criteria for DCD includes:

A. The acquisition and execution of coordinated motor skills is substantially below that expected given the individual’s chronological age and opportunity for skill learning and use. Difficulties are manifested as clumsiness (e.g., dropping or bumping into objects) as well as slowness and inaccuracy of performance of motor skills (e.g., catching an object, using scissors or cutlery, handwriting, riding a bike, or participating in sports).

B. The motor skills deficit in Criterion A significantly and persistently interferes with activities of daily living appropriate to chronological age (e.g., self-care and self-maintenance) and impacts academic/school productivity, prevocational and vocational activities, leisure, and play.

C. Onset of symptoms is in the early developmental period.

D. The motor skills deficits are not better explained by intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder) or visual impairment and are not attributable to a neurological condition affecting movement (e.g., cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, degenerative disorders).relating to clinically relevant anatomy of the condition

The presentation of DCD is often heterogenous in nature and often co-occurs with other conditions, such as attention deficit hyperacticity disorder (ADHD), specific language impairment (SLI), and learning disabilities (LDs). [3] Diganosis of DCD by a physician requires conducting an interview and clinical assessment, taking into consideration family and birth history, as well as inquiry related to the child's attainment of developmental milestones. Physical therapists may play an important role in the diagnosis of DCD; as movement experts, they utilize appropriate developmental screening tools to identify deficits in motor skills in coordination, and can refer to physician for a comprehensive evaluation.

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

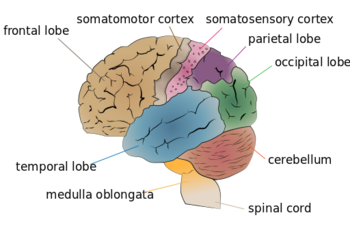

Limited evidence exists related to the etiology of DCD. It is hyptothesized that children born pre-term or very low birth weight are at higher risk of motor impairment, including DCD, and smaller volumes of neuroanatomical structures, such as the cerebellum and basal ganglia have been found in children with DCD, suggesting the possibility of delayed development of these areas in the brain. [4]In addition, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have linked the parietal lobe and parts of the frontal lobe as etiological factors contributing to the diagnosis of DCD.[5]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

DCD may have a heterogenous or variable presentation, and it is often difficult to distinguish between the primary and secondary impairments associated with this condition. Children with DCD may demonstrate delays in achieving gross and fine motor milestones, such as sitting, crawling walking, negotiating stairs, handwriting, and self-dressing (using buttons and zippers), however, many do meet expected milestones in a timely manner. [2] The clinical presentation of DCD is broad, and includes all 4 criterion listed in the DSM-5.[2] Children with DCD can be described as uncoordinated, clumsy or awkward, demonstrating poor postural control; they typically move more slowly, with delayed responses and exert more effort into accomplishing daily living, academic and motor tasks. [6] In general, they have diffculty adjusting movements and adapting to the demands of the environment, and often exhibit deficits in executive function, including motor planning and motor imaging.[6] Consequently, learning new motor skills may be challenging for children with DCD, and they appear to remain in the preliminary stages of learning new tasks, with difficulty transferring and generalizing skills to a novel context. [7] As a result of these challenges, children with DCD tend to be less physically active and may experience excessive weight gain as a result of decreased participation in movement and exercise. [8]As they progress towards adolescence and adulthood, children with DCD often experience decreased self-esteem, and studies have suggested an increased risk of poor mental health outcomes, including depression and anxiety for individuals with a diagnosis of DCD.[9]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Although the DSM-5 criterion describe 4 required characteristics for an accurate diagnosis, a comprehensive medical history, interview, relevant questionnaires, clinical examination and motor tests are all important steps in identifying a child with DCD, and it is recommended that this diagnosis is not provided until the age of 6 years. [6] In most countries, a physician must diagnose DCD, however, parents, educational professsionals and physical therapists, are often the first to recognize atypical motor behavior and deficient skills at home or in the school setting, where it becomes more obvious.[10][6] Differential diagnosis is an important component of the medical evaluation, as neurological disorders associated with clumsiness and lack of motor coordination must be ruled out, including Friedreich's ataxia, cerebral palsy, myopathies, and traumatic brain injury. [6]In addition to an interview of the child and caregiver, the DCDQ (Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire) has demonstrated valid and reliable psychometric properties to assist in identifying children with DCD and is available at no cost at www.dcdq.ca. [11][12] After administration of this tool, based on the child’s age and total score, a physical therapist can determine whether the child may have DCD or is not likely to be affected.[13] In order to assess the DCD criteria of a child with a suspected diagnosis, physical therapists use clinical observation, as well as appropriate outcome measures to identify and assess motor skills, such as the Movement Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd edition (MABC-2), which is considered the gold standard for children ages 3-16 years with a suspected diagnosis of DCD. [6][14]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

add links to outcome measures here (see Outcome Measures Database)

Management / Interventions

[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to management approaches to the condition

Differential Diagnosis

[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to the differential diagnosis of this condition

Resources[edit | edit source]

Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionaire website

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Zwicker JG, Missiuna C, Harris SR, Boyd LA. Developmental coordination disorder: a review and update. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 2012 Nov 1;16(6):573-81.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Edition F. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Am Psychiatric Assoc. 2013;21:591-643.

- ↑ Palisano RJ, Orlin M, Schreiber J. Campbell's Physical Therapy for Children Expert Consult-E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2016 Dec 20.

- ↑ Dewey D, Thompson DK, Kelly CE, Spittle AJ, Cheong JL, Doyle LW, Anderson PJ. Very preterm children at risk for developmental coordination disorder have brain alterations in motor areas. Acta Paediatrica. 2019 Sep;108(9):1649-60.

- ↑ Biotteau M, Chaix Y, Blais M, Tallet J, Péran P, Albaret JM. Neural signature of DCD: a critical review of MRI neuroimaging studies. Frontiers in Neurology. 2016 Dec 16;7:227.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Caçola P, Lage G. Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD): An overview of the condition and research evidence. Motriz: Revista de Educação Física. 2019 Apr 25;25.

- ↑ Smits-Engelsman B, Bonney E, Ferguson G. Motor skill learning in children with and without Developmental Coordination Disorder. Human Movement Science. 2020 Dec 1;74:102687.

- ↑ Joshi D, Missiuna C, Hanna S, Hay J, Faught BE, Cairney J. Relationship between BMI, waist circumference, physical activity and probable developmental coordination disorder over time. Human movement science. 2015 Apr 1;40:237-47.

- ↑ Harrowell I, Hollén L, Lingam R, Emond A. Mental health outcomes of developmental coordination disorder in late adolescence. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2017 Sep;59(9):973-9.

- ↑ Biotteau M, Danna J, Baudou É, Puyjarinet F, Velay JL, Albaret JM, Chaix Y. Developmental coordination disorder and dysgraphia: signs and symptoms, diagnosis, and rehabilitation. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment. 2019;15:1873.

- ↑ Wilson BN, Crawford SG, Green D, Roberts G, Aylott A, Kaplan BJ. Psychometric properties of the revised developmental coordination disorder questionnaire. Physical & occupational therapy in pediatrics. 2009 Jan 1;29(2):182-202.

- ↑ Wilson BN, Kaplan BJ, Crawford SG, Roberts G. The developmental coordination disorder questionnaire 2007 (DCDQ’07). Administrative manual for the DCDQ107 with psychometric properties. 2007 Oct:267-72.

- ↑ Harris SR, Mickelson EC, Zwicker JG. Diagnosis and management of developmental coordination disorder. Cmaj. 2015 Jun 16;187(9):659-65.

- ↑ Henderson SE, Sugden DA, Barnett AL, editors. Movement assessment battery for children - second edition [MABC-2], 2nd ed. London, The Psychological Corporation, 2007.