Developing a Qualitative Research Proposal

Original Editor - Mariam Hashem

Top Contributors - Mariam Hashem, Kim Jackson, Ewa Jaraczewska and Tarina van der Stockt

Introduction[edit | edit source]

A research proposal is a document that describes the idea, importance, and method of the research. The format can vary widely among different higher education settings, different funders, and different organizations[1].

How to Write a Qualitative Research Proposal?[edit | edit source]

Background and context[edit | edit source]

The title of your research proposal can be different from the publishing title. It can be considered a working title that you can revisit later after finishing the research proposal and amend it if needed.

The title should have some keywords of what your research encompasses such as[2]:

- The patient population e.g. women who had breast cancer

- Methods e.g. quantitative research, feasibility study or a pilot randomized control trial, a systematic review

- An intervention

Example: experiences of pregnant women using in-depth focus groups

Word count is similar to writing an abstract and can vary from a proposal to another.

Tips:

- Pin down your key points

- Use the filter approach by starting off broadly then refine it down to our research question.

For example, a qualitative study in Ireland by Naomi Algeo looking at the facilitators and barriers for women with Breast Cancer in returning to work. The author started by looking at Breast Cancer in terms of the statistics nationally and worldwide. Then moved to issues that women with breast cancer experience, highlighting policies and guidelines. To narrow it down, she made it more specific to work and its importance and returning to work after Breast Cancer. The proposal looked at national and cultural differences in return to work in Breast Cancer and highlighted a gap in an Irish context[1].

When thinking of the research proposal, it's your tool to sell the research to probably an ethics committee or a research funder so you want to show them why your research is important to be done. Here are some prompting questions to help with writing the background[1]:

- How much do we know about the problem?

- What are the gaps in our knowledge?

- How would new insights contribute to society? Or to clinical practice?

- Why is this research worth doing?

- And who might have an interest in this topic?

Defining the research question: SPIDER tool[edit | edit source]

Research question(s) give your research a clear focus and guide on the design, research methodology, and data collection. It should be focused and researchable whether through primary or secondary sources. It should be feasible to answer within a given timeframe and it should be specific enough for you to be able to answer thoroughly.

The SPIDER tool is a question format tool and helpful method to structure the research questions. It's similar to the PICO tool which is used for experimental studies:

- P: population

- I: intervention

- C: comparison

- O: outcome.

For qualitative research and mixed methods, we can use the SPIDER Tool[3]:

- S: sample. who is your population? Who do you want to study?

- P and I: the phenomenon of interest. what exactly are we trying to explore? it could be anything like an event, an occurrence, or an object.

- D: the design

- E: the evaluation.

- R: research type.

An example of a research question: what are women with Breast Cancers' experiences of attending a lymphedema clinic?

S = sample is women with Breast Cancer

PI=Phenomenon of interest is the lymphedema clinic. What are their experiences of this phenomenon ( lymphedema clinic)?

D= design which could be a questionnaire, interviews, focus groups, a case study, an observation

E = evaluation, evaluating the experience.

R =research type using a qualitative approach or mixed methods. This something that you need to decide further down the line but will be based on your research question.

After formulating the question(s) you need to look at the way you're going to answer it. Answering the question(s) will depend on the question, the design and research type.

Data collection technique[edit | edit source]

Each design method has its pros and cons and the selection depends on the question, the participants, and the time-scale. For example, looking at the experiences of somebody who's had severe trauma or exploring a sensitive topic, a one to one interview is probably the most appropriate method to respect privacy.

Interviews:

Interviews are typically one to one between the participant and the researcher. They can be structured, semi-structured, or unstructured. The most common approach is probably semi-structured[4].

A structured interview is led by the researcher using a pre-determined set list of questions that all must be answered and there's not a huge amount of flexibility to deviate elsewhere. Every participant is asked the same set of questions, in the same order. This makes it easier to compare answers and is often seen, outside of research, in a job interview format. A disadvantage in qualitative research is that this format doesn’t allow the researcher to prompt and ask other questions which can often build rapport with the participant.[4]

An unstructured interview is a complete opposite in which the researcher can start off by saying something like ''tell me about your experiences at this clinic'' so it's completely by the participant who can deviate to different ways and the researcher can prompt by ''tell me more, tell me more''. Conversations are generally free-flowing and can feel more comfortable however it can make a comparison of data difficult for the researcher. In addition, it may not allow the researcher to cover all aspects that they want to address their research questions.[4]

Whereas the semi-structured interview is somewhere in between. There is a list of some questions to give a structure to the interview with flexibility for the participant to deviate or go in-depth into their answers[5]. This type of interview combines aspects of structured and unstructured interviews.[4]

Pros & Cons[1]:

- Privacy as it calls for trust between the participant and the researcher with a level of transparency but you do need to be able to build rapport which needs some practice.

- More appropriate for discussing sensitive topics

- Interviews can be more in-depth than focus groups and you can get a real sense by digging in deep when you're interviewing someone one to one, as opposed to snippets here and there from a focus group.

- Interviews are time-consuming. However, there is less potential for bias, unlike a focus group in which some participants might dominate the dynamics of the group and people can be led by what others are saying and might not speak about something that comes naturally to them so a one-to-one interview cuts out that bias.

- Interviews can be expensive to run than focus groups due to the time required to run them. Focus groups, on the other hand, can vary between five to fifteen participants. Ideally, eight participants is a good number to be able to manage the conversation while obtaining a number of detailed views. Fifteen or more participants can limit the depth of details and the insight provided on the chosen topic but it can also be a handy way to offer a number of different perspectives in a time-efficient manner.

Focus groups can be more appropriate for identifying group norms, patterns, and opinions. There are lower average speaking times, therefore it's not as in-depth as the interviews. The group dynamics need to be managed which needs some experience from the reseacher[1][7].

The trustworthiness of the findings can be reduced compared to interviews due to the bias when participants tend to provide a desired answer or to be led by others.

Participant observation: where the researcher gets close enough to participants that they observe with or without participation. Participants can be communities or groups where the research aims to gain familiarity with this specific cohort of people.

For example, observing at a religious group, an occupational group, or a community through intensive involvement in their own environment over an extended period of time that could be with participation, direct or indirect observations.

This method can be time-consuming and requires a conscious effort to be objective and gain trust to build a rapport with the group you're observing. The trust is needed to be built to encourage the participants to feel comfortable and natural to eliminate bias[1][9].

Participant recruitment and sampling[edit | edit source]

There is no magic number as to how many people you should recruit in qualitative research. The sample sizes are usually smaller than quantitative research and will depend on a number of variables and some considerations.

When writing a research proposal, it's not good enough to give a vague number instead you need to provide justification and rationale on how you came about to choose the number of participants that you aim to recruit[1].

Considerations:

Study design: there are various methods and approaches to collect your data but not all methods will be relevant to the study question(s). For example, interpretive phenomenological approach or analysis (IPA) calls for smaller sample sizes (3-5 participants)

However, there are cases where some participants in IPA creep up to the double (up to 10-12 people). The reason for the smaller sample size with IPA is to allow for the in-depth collection of data and this is different from observing themes or patterns, by looking at for example, underlying meanings, words, how many things are repeated, and the tone of the language. On the other hand, if we look at thematic analysis it's been suggested to consider between 10-50 participants for participant-generated data by Braun and Clark[10]. For grounded theory, Moore [11]suggested between thirty and fifty participants, whereas Creswell[12] suggested twenty to thirty.

The principles of data saturation. While our sample should be sufficient enough to describe the phenomenon of interest in detail, having a very large sample is a risk of repeating obtained data to the point of limiting the emerging themes, information, and ideas. This is referred to as data saturation. There is a need to balance the sample size to the amount of information we aim to get from the study[13].

Quality over quantity. Recruiting the right participants by setting up clear criteria who meet the right criteria. On some occasions, researchers might not be able to recruit enough participants or reach the planned sample size. However, this is better than recruiting people who don't necessarily match those criteria as this might compromise the results[1].

Recruitment can be online via social media or advertising posters in outpatient clinics

Researchers shouldn't go directly to potential participants to recruit them as they might feel obliged to take part and this is not ethically sound. However, they might use a gatekeeper. A gatekeeper is somebody who's not involved directly in the research but acts as a go-between to advertise the study to participants who would meet the criteria or potential participants.

When thinking about the recruitment methods, you want to choose the most convenient method that will link you the most suitable people[1][14]. for example, if a social media advert might be the most suitable when recruiting participants at a study around e-health. Hence the topic of the study, you want your cohort to be comfortable using computers.

Check out this example for an online recruitment advert.

Sampling approach[1]:

Purposive sampling: is the most common form of sampling. It looks into a very specific cohort of people with very defined characteristics. The inclusion criteria should be very clear for example, if we're looking into women who had Breast Cancer then we get a male participant who shows interest we decline his participation due to the clear inclusion criteria. However, this male participant shouldn't be excluded if the research advert calls for patients who have had Breast cancer so it needs to be as specific as possible.

Snowball sampling: where participants refer other participants who they might know to have similar characteristics for a study.

Convenience sampling: is the different extreme where the inclusion characteristics are accessible, flexible, and not very specific. It's mostly used when the topic is very broad.

Theoretical sampling is when researchers generate theories from emerging data and as these potential theories expand and evolve the selection criteria for our participants can change to align with them.

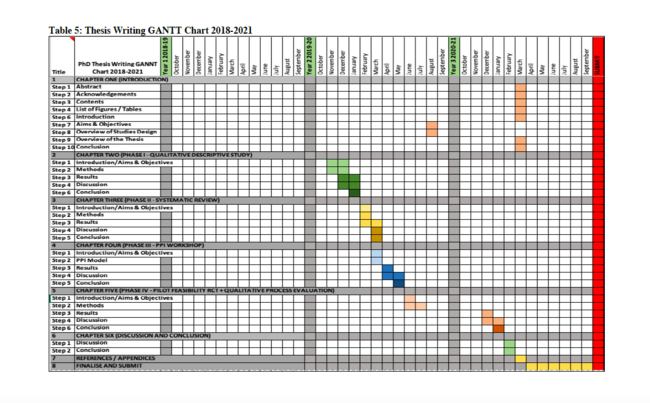

Setting a research timeline: Gantt chart[edit | edit source]

Funders and organizations typically require a pre-set timeline. A Gantt Chart is a visually appealing type of bar chart, that helps to set the research timeline. This chart is often colour-coded and could be divided into timelines such as weeks, months, or quarters.

It's often helpful once you are going with your research to have it pinned on your wall as a reminder of the deadlines or milestones to reach.

The Gantt chart is developed using an Excel spreadsheet and you can find plenty of online tutorials that show you how to do it step by step. Some research proposals might seek the level of detail offered by the Gantt Chart but it may not be necessary to go to those lengths. You could simply bullet point some key milestones or target dates if you're short on time[1].

The landscape Gantt Chart can be very useful to set and to show a realistic timeline of the key milestones that you need to achieve[15].

This Gantt chart was developed by Algeo. It's very colourful, eye-catching but quite detailed to give evidence of the thinking behind the process and giving feasible, realistic time, and key milestones for each stage of the research:

This step might not be essential but definitely desirable supplementary piece that you can add to make your application go the extra mile.

Other considerations[edit | edit source]

Lay abstract: funders are increasingly looking for patient and public involvement (PPI). Some research proposals will call for a lay abstract, in other words, an abstract that is not institutionalized to a specific professional jargon so to make it accessible reading for the public. In order to do make sure that language is accessible you don't want to give it to a colleague who's also institutionalized in that lay language, but maybe to give it to a family member or to a friend who doesn't have a medical or health sciences background to see if they understand it[17].

Referencing: While most funders or research proposals don't call for a specific type of referencing system, it might be worth checking to see but at the to make sure your referencing is consistent throughout[1].

Contingency plans: this is where you need to show the funder or the ethics committee that you are realistic about your timeframes. A useful tip is to put in a buffer for any potential delays which could happen. Think about a contingency plan within your Gantt Chart or your timeline[1]

Budgets and costs: It's advisable to propose all costs, justify these costs and the source you used to calculate this cost. The followings are examples of costs included in the research[1]:

- Travel costs of researchers and participants if applicable

- Materials such as data management software, a dictaphone to record your interviews, refreshments for a focus group participant

- Any training needed

- Any assistance needed such as transcription services, research assistance, time out of your professional duties and any employer compensations needed

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 Algeo N. Developing a Qualitative Research proposal. Physioplus Course 2020.

- ↑ Balch, Tucker. How to Compose a Title for Your Research Paper. Augmented Trader blog. School of Interactive Computing, Georgia Tech University; Choosing the Proper Research Paper Titles. AplusReports.com, 2007-2012; General Format. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

- ↑ Doody O, Bailey ME. Setting a research question, aim and objective. Nurse researcher. 2016 Mar 21;23(4).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Kallio H, Pietilä A-M, Johnson M, et al (2016). Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J Adv Nurs 2016;72: pp: 2954–65.doi:10.1111/jan.13031

- ↑ Batmanabane V. 2017. qualitative data collection interviews. Available from:https://trp.utoronto.ca/students2016/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2016/09/Interviews-JK_VB-V7-March-1.pdf

- ↑ Qualitative interviews #3 How to conduct interviews . Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0QLmii0wiwU[last accessed 14/08/2020]

- ↑ O. Nyumba T, Wilson K, Derrick CJ, Mukherjee N. The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods in Ecology and evolution. 2018 Jan;9(1):20-32.

- ↑ Moderating focus groups. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xjHZsEcSqwo[last accessed 14/08/2020]

- ↑ Smit B, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Observations in qualitative inquiry: When what you see is not what you see. 2018

- ↑ Braun V, Clarke V. Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. sage; 2013 Mar 22.

- ↑ Moore J. Classic grounded theory: a framework for contemporary application. Nurse Researcher. 2010 Jul 1;17(4).

- ↑ Forman J, Creswell JW, Damschroder L, Kowalski CP, Krein SL. Qualitative research methods: key features and insights gained from use in infection prevention research. American journal of infection control. 2008 Dec 1;36(10):764-71.

- ↑ Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, Burroughs H, Jinks C. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & quantity. 2018 Jul 1;52(4):1893-907.

- ↑ Archibald M, Munce S. Challenges and strategies in the recruitment of participants for qualitative research. University of Alberta Health Sciences Journal. 2015;11(1):34-7.

- ↑ The Research Whisperer. 2011. How to make a simple Gantt chart. Available from : https://researchwhisperer.org/2011/09/13/gantt-chart/

- ↑ Qualitative interviews #3 How to Make a Gantt Chart in Excel. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=un8j6QqpYa0[last accessed 14/08/2020]

- ↑ Elsevier.2018.In a nutshell: how to write a lay summary. Available from: https://www.elsevier.com/connect/authors-update/in-a-nutshell-how-to-write-a-lay-summary