Clavicular Fracture

Original Editor - Sofie Van Cutsem

Top Contributors - Elvira Muhic, Sofie Van Cutsem, Manisha Shrestha, Lucinda hampton, Nupur Smit Shah, Kim Jackson, WikiSysop, Claire Knott, Tony Lowe, Naomi O'Reilly and Karen Wilson

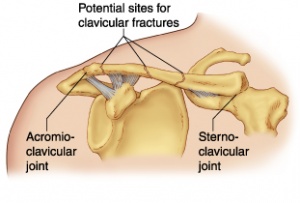

Clinical Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The collarbone (clavicle) is located between the ribcage (sternum) and the shoulder blade (scapula), and it connects the arm to the body.[1] The clavicle is the first bone in the human body to begin intramembranous ossification directly from mesenchyme during the fifth week of fetal life. Similar to all long bones, the clavicle has both a medial and lateral epiphysis. The growth plates of the medial and lateral clavicular epiphyses do not fuse until the age of 25 years.Peculiar among long bones is the clavicle’s S-shaped double curve, which is convex medially and concave laterally. This contouring allows the clavicle to serve as a strut for the upper extremity, while also protecting and allowing the passage of the axillary vessels and brachial plexus medially.[2]

Clavicle Fracture (Broken Collarbone)[edit | edit source]

A clavicle fracture is also known as a broken collarbone.[1] Clavicle fractures are very common injuries in adults (2–5%) and children (10–15%) and represent the 44–66% of all shoulder fractures. Despite the high frequency the choice of proper treatment is still debated. Both conservative and surgical management are possible, and surgeons must choose the most appropriate management modality according to the biologic age, functional demands, and type of lesion.[2]

Mechanism of injury[edit | edit source]

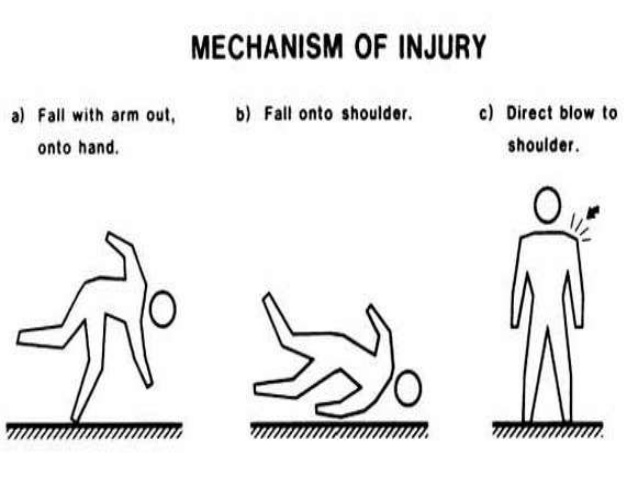

Younger individuals often sustain these injuries by way of moderate to high-energy mechanisms such as motor vehicle accidents or sports injuries, whereas elderly individuals are more likely to sustain injuries because of the sequela of a low-energy fall. Although a fall onto an outstretched hand was traditionally considered the common mechanism, it has been found that the clavicle most often fails in direct compression from force applied directly to the shoulder.[2]

Clavicle fractures are often caused by a direct blow to the shoulder. This can happen during a fall onto the shoulder or a car collision. A fall onto an outstretched arm can also cause a clavicle fracture. In babies, these fractures can occur during the passage through the birth canal.[1]

Clavicle fractures are often caused by a direct blow to the shoulder. This can happen during a fall onto the shoulder or a car collision. A fall onto an outstretched arm can also cause a clavicle fracture. In babies, these fractures can occur during the passage through the birth canal.[1]

Classfication[edit | edit source]

Classification by Allman[edit | edit source]

Multiple attempts have been made to devise a classification scheme for clavicle fractures. The most common system is the following one, created by Allman, in which the clavicle is divided into thirds:

- Type I fractures: Middle third injuries

- Type II fractures: Distal third injuries

- Type III fractures: Medial (proximal) third injuries[3]

Classification by Neer[edit | edit source]

Fractures of the lateral third of the clavicle were further sub classified by Neer, recognizing the importance of the coraco-clavicular (CC) ligaments for the stability of the medial fracture segment.

- Type I lateral clavicle fracture occurs distal to the CC ligaments, resulting in a minimally displaced fracture that is typically stable.

- Type II injuries are characterized by a medial fragment that is discontinuous with the CC ligaments. In these cases, the medial fragment often exhibits vertical instability after loss of the ligamentous stability provided by the CC ligaments.

- Type III injuries are characterized by an intra-articular fracture of the acromio-clavicular joint with intact CC ligaments. Although these fractures are typically stable injuries, they may ultimately result in traumatic arthrosis of the acromio-clavicular joint.[2]

Classification by Robinson (Edinburgh classification)[edit | edit source]

A more detailed classification system (Edinburgh classification) was proposed by Robinson. Similar to earlier descriptions, the primary classification is anatomically divided into medial (type I), middle (type II), and lateral (type III) thirds. Each of these types is then subdivided based on the magnitude of fracture fragment displacement. Fracture displacement of less than 100% characterizes subgroup A, whereas fractures displaced by more than 100% account for subgroup B. Type I (medial) and type III (lateral) fractures are further subdivided based on articular involvement. Subgroup 1 represents no articular involvement, and subgroup 2 is characterized by intra-articular extension. Similarly, type II (middle) fractures are sub-categorized by the degree of fracture comminution. Simple or wedge-type fracture patterns make up subgroup 1, and comminuted or segmental fracture patterns represent subgroup 2.[2]

Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Clinical signs and symptoms of clavicle fracture include the following:

- The patient may cradle the injured extremity with the uninjured arm

- The shoulder may appear shortened relative to the opposite side and may droop

- Swelling, ecchymosis, and tenderness may be noted over the clavicle

- Abrasion over the clavicle may be noted, suggesting that the fracture was from a direct mechanism

- Crepitus from the fracture ends rubbing against each other may be noted with gentle manipulation

- Difficulty breathing or diminished breath sounds on the affected side may indicate a pulmonary injury, such as a pneumothorax

- Palpation of the scapula and ribs may reveal a concomitant injury

- Tenting and blanching of the skin at the fracture site may indicate an impending open fracture, which most often requires surgical stabilization

- Nonuse of the arm on the affected side is a neonatal presentation

- Associated distal nerve dysfunction indicates a brachial plexus injury

- Decreased pulses may indicate a subclavian artery injury

Venous stasis, discoloration, and swelling indicate a subclavian venous injury.[3]

The most common symptoms of a clavicular fracture are: pain in de area of the fracture and crackling of the clavicula. The clavicula has an abnormal contour and the patient is unable to lift his arm due to pain. The patient hold his affected arm adducted and supports with his opposite hand. This position is more comfortable than another because it limits the pull from the weight of the arm on the fractured bone.[4]

Diagnostic procedures[edit | edit source]

Diagnose can often be made by an anamnesis and physical examination.[4] Complications after group III (medial third of the clavicle) fractures resemble those associated with posterior sternoclavicular dislocations, including pneumothorax and compression or laceration of the great vessels, trachea, or esophagus. The medial epiphysis ossifies later than the rest of the clavicle, beginning at age 12-19 years, and may not completely fuse until age 22-25 years. Physial injuries around this area may be mistaken for fractures, and care should be taken in evaluating injuries. Neurovascular injuries, especially those to the ulnar nerve, are also included in the differential diagnosis of clavicle fractures. Other differential diagnoses may be:

- Acromioclavicular Joint Injury

- Hemothorax

- Pneumothorax

- Rib Fracture

- Rotator Cuff Injury

- Scapular Fracture

- Shoulder Dislocation

- Sternoclavicular Joint Injury[3]

Laboratory studies are ordered in clavicle fractures according to the severity of trauma. With suspected vascular injury, obtain a complete blood count (CBC) to check the hemoglobin and hematocrit values. If a pulmonary injury is suspected or identified, perform an arterial blood gas (ABG) test and obtain an expiration posteroanterior (PA) chest film. Other imaging studies that can be used in the assessment of a clavicle fracture include the following:

- Radiography of the clavicle and shoulder

- Computed tomography (CT) scanning with 3-dimensional (3-D) reconstruction

- Arteriography

- Ultrasonography[3]

Conservative Treatment[edit | edit source]

Conservative or non-surgical treatment is the norm for middle-third clavicle fractures, and is recommended for not displaced fractures given the generally low incidence of non-union after conservative treatment of these fractures. There are numerous conservative treatment options available, the most common being the use of a sling or figure-of-eight bandage (also known as figure-of-eight splint, or back-pack bandage), or a combination of these two methods. There appears to be no consensus on the optimal duration of immobilization; some have recommended two to six weeks. Often no subsequent therapy is suggested to the patient. Sometimes, however, a patient will require stretching exercises to regain motion. We prefer to follow the patient with a structured rehabilitation in order to have a satisfactory outcome for most patients. To protect the healing clavicle, it is important to avoid contact sports for a minimum of 4 to 5 months.[2]

Surgical Treatment[edit | edit source]

Surgery is necessary in case of: nerve, blood or pleural injury, a lateral fractures extending to the articular surface, a lateral fracture combined with a rupture of the coracoclavicular ligament, non-ossified fractures which is over de 6 months old and is still symptomatic, a fracture that have high potential for union. [4][5]

Surgical treatment of medial-end clavicle fractures is indicated if mediastinal structures are placed at risk because of fracture displacement, in case of soft-tissue compromise, or when multiple trauma and/or “floating shoulder” injuries are present. [2]

About the middle third clavicle fractures definitive indications for acute surgical intervention include skin tenting, open fractures, the presence of neurovascular compromise, multiple trauma, or floating shoulder. [2]

The indication for surgical treatment of lateral-third clavicle fractures is based on the stability of the fracture segments, displacement, and patient age. The integrity of the CC ligaments plays a key role in providing stability to the medial fracture fragment. Displacement of the medial clavicle is seen when the CC ligaments are disrupted (Edinburgh type 3B).[2]

The treatment of the clavicle fractures is still controversial and debated. The use of plate and screws fixation represents the gold standard in displaced and comminuted fractures. Non-operative treatment is mandatory in not displaced cases.[2]

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=16uwQpOeqFYJ8R36ULpwDiNud: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Clavicle Fracture (Broken Collarbone). www.orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00072

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Paladini, P et al. “Treatment of Clavicle Fractures.” Translational Medicine @ UniSa 2 (2012)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Medscape. Kleinhenz BP, Young CC, Clavicle Fractures. www.emedicine.medscape.com/article/92429-overview#showall

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 M. Pecci, J. Kreher, MD, Boston university, Clavicle fractures, jan. 2008. Level of evidence: 1 Grade of recommendation: B

- ↑ I. Kunnamo, Evidence based medicine guidelines, p. 575, 2005. Level of evidence: 5 Grade of recommendation: E