Sternoclavicular Joint Disorders

Original Editor - Ashley Plawa and Joseph So as part of the Temple University EBP Project

Top Contributors - Mariam Hashem, Joseph So, Admin, Kim Jackson, Ashley Plawa, Rachael Lowe, 127.0.0.1, Tony Lowe, Tarina van der Stockt, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Scott A Burns, Tim Hendrikx, Naomi O'Reilly, WikiSysop, Wanda van Niekerk, Jess Bell and Robin Tacchetti

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

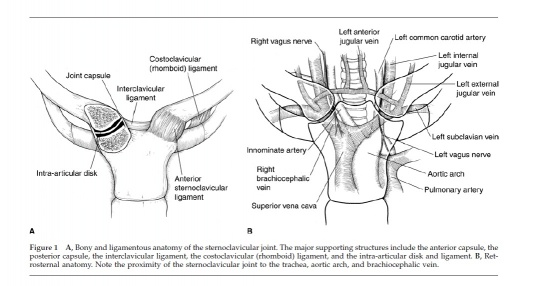

The Sternoclavicular (SC) joint is the only bony joint that connects the axial and appendicular skeletons. The SC joint is a plane synovial joint formed by the articulation of the sternum and the clavicle. Due to the joint’s articulation between the medial clavicle and the manubrium of the sternum and first costal cartilage, the joint has little bony stability. Between the medial clavicle and the manubrium is a dense fibrocartilaginous disc that separates the joints into two distinct synovial compartments.

The intra-articular ligament provides joint stability and prevents medial displacement of the clavicle. This ligament originates from the junction of the first rib and sternum and passes through the SC joint and attaches to the clavicle on the superior and posterior side. The anterior and posterior sternoclavicular ligaments restrain anterior and posterior translation of the medial clavicle. The anterior and posterior sternoclavicular ligaments originate on the anterior and posterior ends of the clavicle, respectively, and insert onto the anterior and posterior surfaces of the manubrium, respectively. The SC joint is supported superiorly by the interclavicular ligament that connects the superomedial portions of each clavicle.

The blood supply to the SC joint is from the articular branches of the internal thoracic and suprascapular arteries.

The SC joint is innervated by the branches of the medial suprascapular nerve. The brachiocephalic trunk, common carotid artery, and the internal jugular vein all lie directly posterior to the SC joint[1].

Figure adapted from: Higginbotham TO, Kuhn JE. Atraumatic disorders of the sternoclavicular joint. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2005;13:138-145.

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

Symptomatic disorders of the SC joint are not very common[3] [4] [5]and are generally due to a high energy traumatic event.[6] Patients with SC joint dysfunction can be classified into two categories based of the mechanism of injury: traumatic or atraumatic.

Traumatic

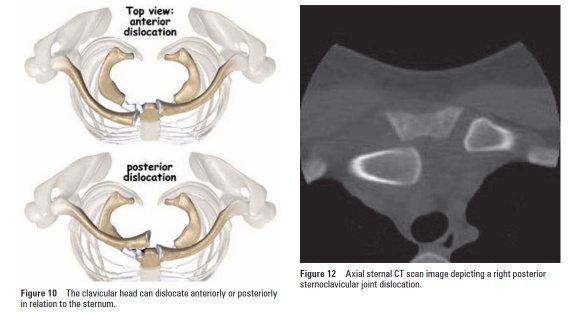

Traumatic injuries to the SC joint range from minor subluxation to complete dislocations. Injuries to the SC joint are rare and infrequently seen in physical therapy. Full dislocation of the SC joint is rare[7] due to a large amount of force and specific vector required to displace the joint. Typically, traumatic injuries to the SC joint occur during falls, sports-related injuries or vehicular accidents. Anterior SC joint dislocations are more common[8][9]. Posterior dislocations have serious clinical implications as the surrounding nerves and vessels may be compromised[10].

A direct trauma by falling laterally to the shoulder, with the force transmitting naturally from the clavicle to the SC joint, can cause either anterior or posterior direct force on the SC joint depending on the arm position[11].

Atraumatic

The SC joint is vulnerable to the same disease processes than occur in joints such as degenerative arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, infections, and spontaneous subluxation of the joint. It is common to have an incidental finding of SC joint osteoarthritis on CT, particularly in older patients.[3] A thorough history is required to determine the presence of non-musculoskeletal disorders[1].

Sternoclavicular joint disorder can result from abnormal motion of the scapulothoracic joint and abnormal scapular motion[11].

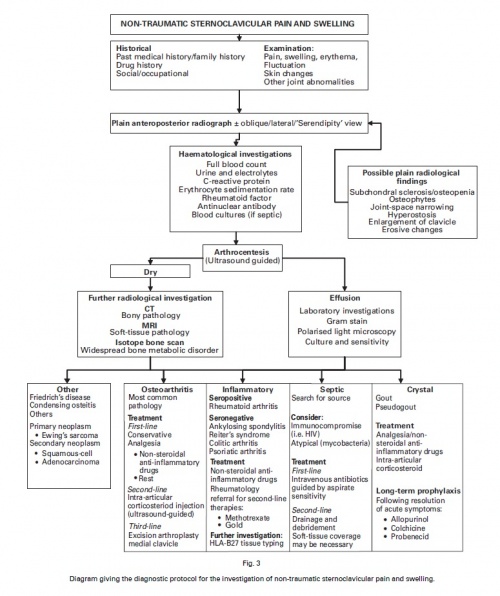

Non-traumatic SC joint pain and swelling might be caused by[11]:

- Osteoarthritis most common pathology

- Inflammatory:

- Seropositive: such as Reactive arthritis (developing response to infections in other parts of the body)

- Seronegative: such as Ankylosing Spondylitis, Reiter's syndrome, Psoriatic Arthritis

- Septic

- Crystal: Gout and Pseudogout

- Other: Friedrich's disease (Spontaneous necrosis that occurs at the medial end of the clavicle), Condensing Osteitis (a benign disorder characterized by sclerosis of the clavicle, but it doesn't affect the SC joint itself), SAPHO (which describes a group of symptoms which are synovitis, acne, pustulosis- an inflammatory skin condition characterized by blisters on the soles of the feet or on the palms of the hands-, hyperostosis which is excess bone growth, and osteitis, which is bone inflammation), Ewing sarcoma, Squamous Cell carcinoma/adenocarcinoma[8]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Traumatic

Patients usually present with complaints of pain and swelling. With mild sprains or subluxations, there may be complaints of instability in the joint. Often with dislocations, a palpable and observable step-off deformity at the SC joint may be present.

Posterior dislocations may be associated with more significant symptoms such as a feeling of compression of the trachea or oesophagus, complaints of dyspnea, choking, difficulty swallowing, or a tight feeling in the throat. In the most severe cases of posterior dislocation, complete shock or pneumothorax may occur and if left untreated and can be associated with complications such as thoracic outlet syndrome and vascular compromise[12].

Classification of Types of Injury[8][9]

- Type I injury is associated with mild to moderate pain associated with the movement of the upper extremity. Instability is usually absent and the SC joint is tender to palpation and may be slightly swollen.

- Type II injury is associated with partial tears in the supporting ligaments. The joint may sublux when manually stressed but will not dislocate. Patients report more swelling and pain than those with Type I injuries.

- Type III injury results in a complete dislocation, either anteriorly or posteriorly, of the SC joint. Patients report severe pain that is aggravated by any movement of the upper extremity. The involved shoulder may be protracted in comparison to the uninvolved side. Patients may also hold the affected arm across the chest in an adducted position and support the involved arm with the contralateral limb.

Atraumatic[1]

- Osteoarthritis (OA) of the SC joint includes: a report of pain and swelling at the SC joint that is aggravated with palpation, ipsilateral shoulder abduction, and/or shoulder flexion about the horizontal. Other findings include osteophyte prominence at the medial end of the clavicle, crepitus, or a fixed subluxation. Degenerative processes of the SC joint become increasingly more common with advanced age. Postmenopausal women are more susceptible than premenopausal women or men.

- Rheumatoid arthritis, RA, of the SC joint includes a report of swelling of the SC joint, tenderness of the SC joint, crepitus, and painful limited movement of the shoulder. Other findings include synovial inflammation, pannus formation, bony erosion, and degeneration of the intra-articular disc. Isolated joint involvement is rare. It is more common to see multiple joints affected with RA and often is present bilaterally.

- Infection of the SC joint includes a report of pain, swelling of the SC joint, tenderness around the SC joint, fever, chills, and/or night sweats. A definitive diagnosis is found with aspiration or open biopsy. Septic arthritis is associated with infection of the SC joint and is seen in patients that have RA, sepsis, infected subclavian central lines, alcoholism, or HIV. It is also seen in immunocompromised patients, renal dialysis patients, and intravenous drug users.

- Spontaneous anterior subluxation includes a patient report of a “pop”, or sudden subluxation of the medial end of the clavicle. It is commonly seen in patients in their teens and twenties who demonstrate ligamentous laxity and may occur with overhead elevation of the arm.

- The clinical presentation of seronegative spondyloarthropathies is similar to that of patients with ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, Reiter’s syndrome, or colitic arthritis. This disorder is characterized by age of onset before 40 years old, inflammation of large peripheral joints, and absence of serum antibodies. Patients present with unilateral involvement, swelling, and tenderness of the SC joint, and pain with full arm abduction.

- Sternocostoclavicular hyperostosis includes soft tissue ossification and hyperostosis, or excessive growth of bone, between the clavicles. A patient with sternocostoclavicular hyperostosis may report localized pain, swelling and warmth over the SC joint. Symptoms are often bilateral and the range of motion of the shoulder can be affected.

- Condensing osteitis includes: patient report of pain and swelling over the affected area. Symptoms are usually unilateral and present in women in their late childbearing years. This condition presents with sclerosis and enlargement of the medial end of the clavicle.

- Friedrich’s disease (aseptic osteonecrosis) includes discomfort, swelling, and crepitus of the SC joint in absence of trauma, infection, or other symptoms. The patient reports loss of ipsilateral shoulder range of motion.

The following table summarizes the main differences between the non-traumatic causes of SC disorders[11][8]:

|

Conditions |

Demographics | Clinical/Lab Findings | Radiological Features |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Systematic Arthritis |

|||

|

Osteoarthritis |

>50 YOA |

Normal |

OA Changes |

|

Rheumatoid Arthritis |

Women any age |

?RH +ve | NOrmal/erosion |

|

Seronegative Spondyloarthropathies |

Men <40 YOA |

+ve HLA-B27 | Normal/erosion |

|

Crystal Arthropathies |

Men >40 YOA |

Joint fluid, elevated ESR (acute) | Secondary OA changes, soft tissue calcifications |

|

Infective Conditions |

|||

|

Septic Arthritis/Osteomyelitis |

Any age |

Systematic Signs +ve Blood tests |

Associated Periosteal Changes |

|

Joint Specific Conditions |

|||

|

SAPHO Syndrome |

Middle-aged adults |

Skin changes ESR/CRP mildly elevated |

Erosive changes

Ossification of ligament insertion |

Signs and symptoms of SC dysfunction:[11][13]

- Tenderness on palpation

- Local Swelling

- Localized pain with elevation above 100°

- Pain with active protraction and retraction

- Referred neck, shoulder, and/or arm pain

Differential Diagnosis[1][10][14][edit | edit source]

- Osteoarthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Septic arthritis

- Atraumatic subluxation

- Seronegative spondyloarthropathies

- Crystal deposition disease

- Sternocostoclavicular hyperostosis

- Condensing osteitis

- Friedrich’s disease (aseptic osteonecrosis)

- SC/AC joint dysfunction

- Sternal Fracture

- Clavicular Fracture

- Anterior dislocation of the SC joint

- Posterior dislocation of the SC joint

The figure below depicts a differential diagnosis flowchart for non-traumatic injuries of the SC joint.

Figure adapted from: Robinson C, Jenkins P, Markham PBI. Disorders of the sternoclavicular joint. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. June 2008;90-B(6):685-696.

Biomechanics[edit | edit source]

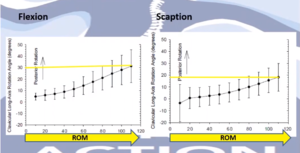

The clavicle shape is convex anteriorly at the medial end and is concave anteriorly at the lateral end. It plays an integral role in maintaining the subacromial space capacity during arm elevation. the clavicle posteriorly rotates and elevates during shoulder flexion, scaption and arm elevation.[15] The posterior rotation of the clavicle results in the elevation of its lateral end where it articulates with the acromion forming the Acromioclavicular joint. This elevation will raise the acromion, maintaining the subacromial space during arm elevation above the head.

With Scaption, at 30 degrees anterior to the coronal plane, there is about 20 degrees of posterior rotation to elevate the lateral end of the clavicle to optimize the space under the acromion, maintaining that subacromial space.

Posterior rotation is an important movement of the joint that needs to be assessed. As the range of elevation increases, the posterior rotation increases[16].

Posterior clavicle tilting is associated with posterior rotation and elevation of the scapula. Therefore, the scapular movement on the thorax might be limited by SCI dysfunction.[15]

These movements will have an effect on the acromion and ultimately the subacromial space, the clavicle, and the SCJ and any small proximal movement limitation around the SCJ will cause a bigger limitation of the distal movement[11].

The graphs show increased clavicle posterior rotation with arm flexion and scaption:

Scapular movement associated with arm elevation

- Upward rotation, inferior angle moving away from the midline

- External rotation, medial border of the scapular moving towards the chest wall

- Posterior tilt where the inferior angle of the scapula moves towards the chest wall.

These motions depend on the freedom of mobility on the thoracic spine

The Serratus Anterior is a massive and important muscle for the scapula. It functions to:

- Upwardly rotates the scapula

- Posteriorly tilts the scapula

- Externally rotates the scapula

- Protracts the scapula

Protraction and retraction around the shoulder are associated with elevation at the SCJ and tightness of the costoclavicular ligament. Depression causes contact through the SC disc and tightness of the interclavicular ligament. Retraction is limited by the anterior part of the sternoclavicular ligament and some compression through the disc.

Protraction and retraction of the clavicle occur with scapula internal and external rotation.

Influence of the thoracic spine on the upper limb movement

- Significant trunk extension occurs with arm movement (12-15° with bilateral arms extension), (6.7-8° with unilateral extension)

- Trunk side flexion and axial rotation occur with unilateral arm movement[17]

- It contributes to 55% of upper limb force generation

- Upper limb injury risk increases three times in cases of reduced thoracic spine rotation flexibility [18]

- When thoracic rotation is included in injury prevention programmes it was found to reduce the injury rate of the shoulder by 28%[19]

- It contributes to 80% of Upper limb rotation

Assessment of the SCJ[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Plain radiographs are indicated at the initial evaluation for SC joint disorders[1]. Computed Tomography (CT) scans are indicated for disease processes in which there is bony destruction or ossification. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) provides information about whether there is inflammation, soft tissue masses, or osteonecrosis are present. While an MRI radiograph is very thorough, CT is a preferred imaging modality in acute settings due to speed, availability, and the ability to discern between soft-tissue and bony injuries, especially in acute scenarios[12]. Laboratory studies may help rule in or rule out a certain diagnosis when inflammatory or infectious disease processes are suspected, such as RA, septic arthritis, or osteomyelitis.

Radiographic evaluation for SC joint dislocations includes standard antero-posterior (AP) radiographs of the chest that may suggest an injury to the SC joint[10]. This may, however, not be the best view for visualization of the joint. The use of the serendipity view radiograph has been shown to be of better diagnostic reliability since it is a bilateral view of the SC joint.

Figures adapted from: Bontempo N, Mazzocca A. Biomechanics and treatment of acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joint injuries. British Journal of Sports Medicine. April 2010;44:361-369.

Physical Examination[edit | edit source]

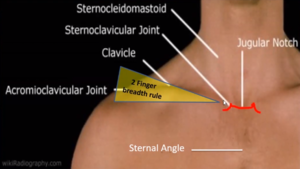

1-Surface marking palpation:

It is easy to palpate the SC joint by finding the jugular notch then move laterally to palpate the joint surface.

The sternal angle, often called the angle of Louis, can be felt at the point where the sternum projects the furthest part forward. This prominent surface mark can be used as a mark of the second rib articulation.

In an optimally positioned shoulder, the scapula is upwardly rotated. The distance between the medial and lateral ends of the clavicle would roughly equal the breadth of two raised fingers. You can use a way of reference is to use the ''rule of finger''. The inclination of the clavicle from medial to lateral ends should roughly equal a two-finger breadth rise. This inclination gives some indication of the scapular upward rotation behind the clavicle [11].

2-Muscular Assessment

The Subclavius, lies just behind the pectoralis major muscle. It originates from the first costochondral junction and inserts in the inferior surface of the lower end of the clavicle tubercle. An active trigger point in this area has a C5/6 referral pattern to the arm [20].

To assess the Subclavius, the patient lies down comfortably on their side and protracts their shoulder while maintaining the Pectoralis Major relaxed. You can palpate the Subclavius by moving your fingers from the medial end of the clavicle to the underside of the bone. The muscle is felt at the area between the middle and lateral third. If you palpate underneath this angle you can feel the insertion of Subclavius. Apply some pressure on the insertion and ask the patient how they feel? This can be tricky because the pressure in this area will be uncomfortable anyway so it might be useful to assess the asymptomatic side first then check the painful side and see how your patient feels.

If the patient reports the C5/6 referral on their arm, this indicates an active trigger point which can be treated by Digital Ischemic Compression. Discuss this treatment with your patient and explain to them that it might take some time to release the muscle[11].

Clinical Tip: to make sure you are palpating the Subclavius and not the Pectoralis Major, ask the patient to contract it first then relax then you can work on finding the Subclavius[11].

Serratus Anterior

We can assess the SA with the following test:

- Patient's arm in about 130° of flexion

- Palpate the inferior angle of the scapula between your thumb and forefinger and produce a downward force while the patient resists you by pushing their arm down

- Then the patient elevates their shoulder then you can push to bring their arm down.

- The aim is to assess what moves first the scapula or the arm. If the scapula downwardly rotates before the arm moves then it indicates insufficiency of scapular upward rotation.

Scalene:

Scalene cramp test

Ask your patient to rotate their head and then side-flex by getting their chin down into the supraclavicular fossa on the side that you want to test. Wait till you see if they start to get local or referred pain and see if they are able to hold this position for 30 seconds. The test is positive if the patient gets a cramp.

3-Assessment of joint play and mobility (compare symptomatic to non-symptomatic side):

Assessment of distraction mobility: patient seated. Stand behind your patient, one hand fixing the Manubruim and the other placed on the axis of the clavicle. Take a skin slack and apply a slight distraction to feel the movement in the joint.

Assessment of posterior glide: with your patient lying down in supine position, palpate the SCJ. Ask your patient to raise both arms to shoulder height level and actively protract their shoulders. Check if the joint rotates posteriorly during this movement by comparing the movement on both sides.

Assessment of inferior glide: with your patient lying down in supine position, palpate the SCJ. Ask your patient to elevate (shrug) their shoulders and check if the joint glides inferiorly.

Assessment of posterior rotation: this might be a difficult movement to assess. With your patient lying down in supine comfortable, sit behind the patient, and glide your fingers underneath the posterosuperior edge. You can assess the movement while the patient fully elevates their arms or moves them into abduction. There should be about 30 ° of rotation in the posterosuperior surface with the shoulder flexion. The ligaments tighten to limit this movement after 45° of posterior rotation, unlike with anterior rotation where the movement is limited after 10% of its ROM[11] increasing the joint compression to protect the joint stability. The costoclavicular ligament is the most important structure in restraining the posterior rotation.

4-First Rib Assessment:

Elevation compression test:

Aim: check if the first rib is elevated

The patient is seated comfortably. Stand behind your patient, your hands over the Upper Trapezius just behind the supraclavicular fossa, then gently feel if there is any rising of the first rib while the patient takes a deep breath and compare both sides.

Rotation Side flexion:

Ask the patient to rotate their head to the shoulder on one side as far as they can then apply passive flexion to the head and compare the ROM on both sides. Rotation to the right shoulder assesses the first rib elevation on the left side. If the first rib is elevated it will block the spinous process of C7 and that will reduce that range.

A possible cause for elevated rib is Anterior Scalene muscle that inserts into the first rib. The muscle comes from the transverse processes of the third to the sixth cervical vertebrae then it passes onto the Scalene tubercle of the first rib behind the Sternocleidomastoid.

5-Assessment of the thoracic spine

The combined elevation test

In this test, the patient lies prone on the bed with their arms outstretched and their fingertips, feet, hips, chest, and chin in contact with the bed. The dominant hand is placed over their non-dominant hand. Ask the patient to keep their head down and lift their arms as high as they can, keeping their head down, then measure the distance between the ulnar styloid process and the bed.

If the patient can't perform this actively then you can check it passively.

If they can get the range passively, then it indicates muscle insufficiency.

If you can't passively change that, then it can be muscle tightness that needs to be addressed.

This can be a limitation to overhead shoulder movement and can cause other structures to compensate.

Seated trunk rotation

The patient in this test sits comfortably with their feet on the floor, place a ball between their knees to keep their pelvic square. We can use a pole for reference. Ask the patient to rotate their trunk to the left and right.

Smartphone applications are available to record the exact angle of rotation around the shoulder.

A study conducted by the English Institute of Sport validated this test for using a digital inclinometer or an iPhone when measuring thoracic spine rotation from a quadruped position, known as the locked lumbar position. The inclinometer is positioned at C7/T1 junction of the patient's spine. The patient rotates while maintaining their head still without rotation. They can put their hand behind their head to keep the alignment and get some range of motion. This has been shown to be a valid way of measuring the thoracic spine rotation.[27]

The physical examination of a patient with a suspected SC joint injury may also include the following:

- Screening of the cervical spine

- Active and passive range of motion of the associated shoulder region, AC, and SC joints

- Observation and palpation of key structures/regions

- Resistive testing of the shoulder region

- Functional testing

Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

Considerations in Dysfunctional SCJ[11]:[edit | edit source]

Articular:

- Hypermobile (lax joint).

- Hypomobile (stiff joint). The SCJ tends to be hypomobile without trauma

- First Rib Position

Myofascial:

- Subclavius (lack of extensibility)

- Sternocleidomastoid (overactivity/lack of extensibility)

- Scalene

Little evidence exists for the optimal management of SC joint dysfunction, but it might be impairment and patient-response driven. The physical therapist may consider exercises, manual therapy techniques, education, or other treatment interventions based on the observed impairments. Often times, SC dysfunction does not require an extensive course of physical therapy.

Initial physical therapy interventions may include:

- Mobility exercises including AROM, AAROM, PROM of the shoulder

- Resistive strengthening

- Motor control training

- Scapular stabilization

- Manual therapy directed at the SC joint, GH joint, and AC joint

Acute and Postoperative Management

In severe, acute traumatic dislocations, reduction of the joint may be required by the appropriate medical provider. Posterior dislocations of the SC joint should be considered a medical emergency due to the proximity of major arteries, nerves, trachea, oesophagus and lungs. Before actual physical therapy is applied, the clavicle should be placed back into the Sternoclavicular joint.[29]

When the patient has an anterior dislocation, most authors recommend at least one closed reduction attempt. This reduction may be performed under local anaesthesia, under sedation, or under general anaesthesia. Place the patient with his arm supine and with a thick pad between his shoulders. The reduction entails abduction of the shoulder to 90 degrees, 10 to 15 degrees of extension, and traction on the arm with posterior pressure over the sternal end of the clavicle.[29]

When the patient has a posterior dislocation, the closed reduction should also be applied under general anaesthesia. There are several techniques described, the standard abduction traction technique is similar to the technique used for anterior dislocations. Place the patient with the shoulder of the injury side supine near the edge of the table with a thick pad between the scapulae. Apply lateral traction with the arm in abduction and extension. The clavicle can be grasped with the fingers to dislodge it from behind the sternum, if the reduction is not succeeded. If the clavicle is still dislocated, use a towel clip to grasp it and it is lifted back into position. This procedure is always done with sterile technique. When the clavicle is reduced after a posterior dislocation it is usually stable.[29]

Surgical stabilization is not recommended by most authors because of the risks for complications such as infections. This type of stabilization should only be used in patients who have failed conservative treatment.[29]

If the Sternoclavicular joint is unstable, let the patient use a sling for a few weeks until symptoms resolve. This is followed by a progressive program to regain normal range of motion and a progressive strengthening program. This strengthening program focusses on the deltoideus and trapezius since they are dynamic stabilizers. [29]

After reduction, physical therapy for anterior and posterior dislocation is similar. Beginning with immobilization of the shoulder in a position of scapular retraction. This depends on the stability of the joint. If the dislocation is stable, the patient is immobilized in a figure-of-8 dressing sling for 6 weeks.[30],[29]

On the second day allow the patient to perform gentle pendulum exercises but caution him against active flexion or abduction of the shoulder above 90°.[31] [32]

On the 4th day after surgery start gentle physical therapy. This therapy should be focused on passive glenohumeral motion, including internal rotation and external rotation.[33]

If the joint is stable at week 3, start elbow exercises and glenohumeral rotation. These exercises include active flexion, extension, abduction and internal/external rotation as well as static strengthening exercises. To prevent the shoulder from dislocating again a good guideline is to keep the hand in view during the first three weeks.[29]

The first 6 weeks abduction or other significant SC joint motion is not allowed. After 6 weeks institute more aggressive range of motion exercises including overhead activities with slow integration of strengthening manoeuvers.[33]

Beginning at 8 to 12 weeks, start a rehabilitation program of stretching and strengthening exercises.[31][32]

Non-operative Management[11]

There is little attention given to the SC joint in the literature in terms of non-operative management

Management of elevated first rib:

Muscle energy techniques can be used also for elevated first rib as well as thoracic outlet syndrome. This useful but often uncomfortable technique is suggested:

- The patient sits relaxed and leaning to the affected side

- Apply contact with your middle phalanx of the index finger over the flat bony part of the first rib. As the patient goes in side-flexion with their trunk apply side-flexion on the cervical spine as well then push down on their first rib and take up the slack.

- Then ask the patient to deep a breath and hold it for about five seconds. As the patient holds their breath, they're going to push their left ear into your hand at about 25% of their maximum force and hold it there and then breathe out.

- As the patient breathes out, we should get a little relaxation of the muscle insertion into the first rib, and feel a little more glide down on their rib.

- Repeat this for two to three times until you stop feeling any movement of the rib.

- You can check if this helped or not by comparing the side flexion and rotation and compare it on both sides (refer to the assessment of the first rib above.

Scalene MET:

- The patient sits with their hand hooked on the side of the bed/chair and looking towards the affected shoulder

- Ask the patient side-flex their head away then take a deep breath in.

- Hold the breath then exhale it out as they get more movement in the side flexion.

- Repeat three or four times and ask the patient to do this regularly at home.

Scalene release test

The patient sits with their hand on their forehead, then ask them to elevate their elbow above their head. This movement should open up a space for the Brachial plexus and the Scaleni and reduce their symptoms.

Another stretching technique in this video:

Sternocleidomastoid

Ask your patient to fix the shoulder girdle by depressing their shoulder and rotating their head away from the symptomatic side then ask them to side flex, rotate with some retraction, and hold that position.

Breathing mechanics is important if there is a problem in scalene or the Sternocleidomastoid. Problems such as suboptimal breathing, apical breathers can be present with these disorders so it's worth checking and correcting the breathing patterns.

Manual Therapy

Improve inferior glide

Palpate the joint lines, on the medial end of the clavicle, and apply a mobilization with movement. Then passively elevate the shoulder achieving inferior glide on the SCJ.

You can pad the SCI when applying this pressure underneath your fingers as it might be uncomfortable for the patient

Also, you can ask the patient to elevate the shoulder actively and assess the angle at which the pain starts at, for example, 110 degrees of elevation, you could ask the patient to stop in this position and apply the inferior glide mobilizations.

You can also use MET technique by palpating the joint line from the medial end of the clavicle then ask the patient to depress their shoulder girdle against resistance by pushing down for a few seconds then they relax. When the patient releases the resistance you can move their shoulder girdle into elevation and feel if the inferior glide was improved or not. This can be repeated a few times.

You can use your body weight to give your patient the resistance needed for this technique, for example, they can push against your thigh instead of your arm. Look for generating about 30% of maximum force.

Improve posterior glide

Patient in the supine position. you can start by feeling the medial end of the clavicle over the joint line there then ask the patient to put their hand over the top of your shoulder and hold the arm then retract their scapula towards the midline and hold this for about four seconds with about 30% of maximum force then ask the patient to relax. Follow that with moving into protraction and repeat for three or four times.

Improve posterior rotation

The Patient is lying on their side. Palpate the posterior superior aspect and align your arms perpendicularly to it. Then ask the patient to move into elevation as you come around and back with your hand facilitating the posterior rotation. You'll need to move your body so that your angle is always creating that posterior rotation.

You can also try to produce the same movement by mobilizing the clavicle at the ACJ using the scapula. The patient lying on the side and you're standing behind the patient. Encourage the patient to posteriorly tilt their scapular, which will then cause posterior rotation. Put your thumb on the anterior inferior edge of the clavicle to facilitate the movement. Be careful as this might cause discomfort to your patient. This can be combined with the patient performing arm elevation but make sure you get your head out in a way when they move up to make it a functional movement.

Thoracic extension manual therapy

There are some techniques that can be used such as lying over a foam roller and apply self-mobilisation or self SNAGs.

Another technique: the patient sits relaxed forward, resting on the bed with their arms externally rotated. Find the level of dysfunction in their thoracic spine. Knowing the average inclination of the facet joints in the thoracic spine is about 60 degrees, you can apply a steadying force with a towel around their trunk with some gentle extension mobilizations.

Overhead squatting is a functional exercise to improve thoracic rotation suggested by Howe and Read 2015 [38]. Designed to help people who are unable to get their arms above their head. You can use the power of a band to do a self SNAGs. the power band is hooked under the thoracic spinous process, attached to a frame, patient squat sand encourages that sternal lift and thoracic extension.

Improving thoracic rotation

Using a PNF pattern. The patient is side-lying on the floor with knees together and rotates and opens up their thoracic spine.

Serratus Anterior exercises

Serratus dynamic hook exercise incorporates the kinetic chain. A band is placed around the back to encourage resistance in protraction.

Dynamic punch also incorporates the kinetic chain with some trunk rotation working the Serratus anterior as a protractor.

Pushup plus. works the Serratus as a protractor

A study by Castelein and Ann Cools[39] looked at the recruitment between Serratus Anterior and Pectoralis Minor, with these exercises: Serratus punch, floor pushup, and wall pushup and studied the EMG output.

The study found:

- Serratus punch resulted in 63% recruitment of Pec minor compared to Serratus.

- Floor pushup generated 93% as much Pec minor activity as Serratus.

- Wall pushup had about 97% as much activity of Pec Minor as Serratus.

Overactive Pec Min causes downward rotation of the scapular, internal rotation of the scapular and anterior tilt of the scapular. These actions are Completely opposite of what we need the scapular to do in elevation.

Scapular Upward Rotation exercises:

Scapular upward rotation: encourage the patient to concentrate on the feeling of their scapular coming round and up above the head.

Modified Cuban press on a Swiss ball: scapula moving into a posterior tilt and down, external rotation, posterior tilt and elevation from there.

Modified upright row: posterior tilt and upward rotation at the scapular.

Scapular Upward rotation on a foam roller with a band: patient prone holding a band and supporting their symptomatic arm on a foam roller to reduce the friction. Scapular should go into an upward rotation as the patient elevates through pushing up through their scapula. Cue the movement and encourage motor control.

The Lower Trap can be responsible for the lack of scapular posterior tilt. To improve this movement, the patient can exercise from prone and lift their arms away from the bed/table/plinth as they concentrate on the posterior tilt. Then you can progress this movement by adding some load by extending the arm against the resistance of a band. Teach your patient to achieve the posterior tilt, not retraction.

If the patient is retracting their shoulder, then we need to address their Rhomboid which are the downward rotator.

Once the patient learns the movement, we can move into functional training by incorporating the kinetic chain.

Kinetic chain exercises

1- patient presses a Swiss ball against the wall, as they recover from squatting they elevate their arms and maintain scapular upward rotation. A power band can be used to add some resistance hooked over the shoulder and around the foot, doing exactly the same movement and making sure the scapular is upwardly rotated and they're not using the elevation of the shoulder.

If the patient still elevates their shoulders, we can assess their levator scapulae.

Bdaiwi et al [41] looked at maintaining the acromial-humeral distance ''subacromial space'' while stimulating lower Trap, Serratus Anterior, and both Serratus and Lower Trap. Stimulating the lower Trap increased the size of the subacromial space. The space has further increased by the stimulated Serratus. The maximum increase was noted when both muscles were stimulated. This can reflect on your assessment strategy and your choice of exercises

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

There are not any specific outcome measures that specifically look at the SC joint but the following could potentially be used as SC joint injury outcome measures since SC joint injuries typically impact upper extremity function:

- DASH

- QuickDASH

- Penn Shoulder Score

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Higginbotham TO, Kuhn JE. Atraumatic disorders of the sternoclavicular joint. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2005;13:138-145.

- ↑ The Sternoclavicular Joint. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tr3bNRb2Iso [last accessed on: 2020/07/20]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Lawrence CR, East B, Rashid A, Tytherleigh-Strong GM. The prevalence of osteoarthritis of the sternoclavicular joint on computed tomography. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(1):e18-e22.

- ↑ Hellwinkel JE, McCarty EC, Khodaee M. Sports-related sternoclavicular joint injuries. The Physician and Sportsmedicine. 2019 Jul 3;47(3):253-61.

- ↑ Sernandez H, Riehl J. Sternoclavicular joint dislocation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 2019 Jul 1;33(7):e251-5.

- ↑ Garcia JA, Arguello AM, Momaya AM, Ponce BA. Sternoclavicular joint instability: symptoms, diagnosis and management. Orthopedic Research and Reviews. 2020;12:75.

- ↑ Obremskey WT, Rodriguez-Baron EB, Tatman LM, Pesantez RF. Acute Dislocations of the Sternoclavicular Joint: A Review Article. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2022 Feb 15;30(4):148-54.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Robinson C, Jenkins P, Markham PBI. Disorders of the sternoclavicular joint. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. June 2008;90-B(6):685-696.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Wirth MA, Rockwood CA. Acute and chronic traumatic injuries of the sternoclavicular joint. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 1996;4:268-278.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Bontempo N, Mazzocca A. Biomechanics and treatment of acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joint injuries. British Journal of Sports Medicine. April 2010;44:361-369.

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 Horsley I. Stenoclavicular Joint Disorder Course. Plus 2020.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Groh GI, Wirth MA. Management of traumatic sternoclavicular joint injuries. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. January 2011;19(1):1-7.

- ↑ Van Tongel A, Karelse A, Berghs B, Van Isacker T, De Wilde L. Diagnostic value of active protraction and retraction for sternoclavicular joint pain. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2014 Dec 1;15(1):421.

- ↑ Gaunt BW, Boers, T. SC, AC, & spinal specific manual techniques can dramatically increase shoulder girdle elevation. Presented at: Combined Sections Meeting; Feb 10, 2011; New Orleans, LA.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ludewig PM, Behrens SA, Meyer SM, Spoden SM, Wilson LA. Three-dimensional clavicular motion during arm elevation: reliability and descriptive data. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2004 Mar;34(3):140-9.

- ↑ Ludewig PM, Reynolds JF. The association of scapular kinematics and glenohumeral joint pathologies. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2009 Feb;39(2):90-104.

- ↑ Heneghan NR, Webb K, Mahoney T, Rushton A. Thoracic spine mobility, an essential link in upper limb kinetic chains in athletes: a systematic review. Translational Sports Medicine. 2019 Nov;2(6):301-15.

- ↑ Aragon VJ, Oyama S, Oliaro SM, Padua DA, Myers JB. Trunk-rotation flexibility in collegiate softball players with or without a history of shoulder or elbow injury. Journal of athletic training. 2012 Sep;47(5):507-15.

- ↑ Andersson SH, Bahr R, Clarsen B, Myklebust G. Preventing overuse shoulder injuries among throwing athletes: a cluster-randomised controlled trial in 660 elite handball players. British journal of sports medicine. 2017 Jul 1;51(14):1073-80.

- ↑ Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial pain and dysfunction: the trigger point manual. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1983.

- ↑ Treatment of the Subclavious Muscle. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-lv5pg3Ubv4 [last accessed 26/07/2020]

- ↑ Muscle Testing - Serratus anterior. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DktiK1UbNNo [last accessed 26/07/2020]

- ↑ Scalene cramp test. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=67ohFsq76RA [last accessed 26/07/2020]

- ↑ How to assess and treat the sternoclavicular joint (SCJ) using METs. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a7YZId29crI[last accessed 26/07/2020]

- ↑ Cervical Rotation/Lateral Flexion Test of First Rib Mobility. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cizcbCrNc98[last accessed 26/07/2020]

- ↑ Combined elevation test for shoulder mobility & strength. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6R1XIODti9E[last accessed 26/07/2020]

- ↑ Bucke J, Spencer S, Fawcett L, Sonvico L, Rushton A, Heneghan NR. Validity of the digital inclinometer and iphone when measuring thoracic spine rotation. Journal of athletic training. 2017 Sep;52(9):820-5.

- ↑ Seated Thoracic Rotation Test. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FILXID53OYA[last accessed 26/07/2020]

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 29.6 MacDonald, e. a. (2008). Acromioclavicular and Sternoclavicular Joint Injuries. Orthopedic clinics of North America, 535-545.

- ↑ Kisner, e. a. (2002). The Shoulder and Shoulder Girdle. In therapautic exercise, Foundations and Therniques , 319-385.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Groh, e. a. (2011). Treatment of traumatic posterior sternoclavicular dislocations. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery, 107-113.fckLRLevel of evidence: 4

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Rockwood, e. a. (2010). Resection Arthoplasty of the Sternoclavicular Joint. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, 387-393.fckLRLevel of evidence: 1b

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Battaglia, e. a. (2005). Interposition Arthroplasty With Bone-Tendon Allograft: A Technique for Treatment of the Unstable Sternoclavicular Joint. J Orthop Trauma, 124-129.fckLRLevel of evidence: 4

- ↑ First Rib Adjustment - Supine A/P. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2J177AYhInc[last accessed 26/07/2020]

- ↑ best scalene muscle stretch - scalene trigger points - neck stretch - scalene neck stretch. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E5AJlLAmWxU[last accessed 26/07/2020]

- ↑ S C M (Sternocleidomastoid muscle) StretchAvailable from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DVebkG8aDG4[last accessed 26/07/2020]

- ↑ SC Joint Posterior Glide Mobilization) Stretch. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cGMhIYOxQWc last accessed 26/07/2020]

- ↑ Howe L, Read P. Thoracic spine function: assessment and self management. Professional Journal of Strength and Conditioning. 2015;39:21-31.

- ↑ Castelein B, Cagnie B, Parlevliet T, Cools A. Serratus anterior or pectoralis minor: which muscle has the upper hand during protraction exercises?. Manual Therapy. 2016 Apr 1;22:158-64.

- ↑ SWISS BALL CUBAN PRESS. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bGY41eCy1BU [last accessed 26/07/2020]

- ↑ Bdaiwi AH, Mackenzie TA, Herrington L, Horsley I, Cools AM. Acromiohumeral distance during neuromuscular electrical stimulation of the lower trapezius and serratus anterior muscles in healthy participants. Journal of athletic training. 2015 Jul;50(7):713-8.