Cerebellar Ataxia - A Case Study

Abstract[edit | edit source]

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Cerebellar ataxia is a condition that can have a multitude of different causes and result in a wide variety of symptoms. Ashizara and Xia (2016) defined ataxia as “impaired coordination of voluntary muscle movement” and explain that it is primarily the result of cerebellar damage. As a result of the cerebellum’s divisions and functional segregation, lesions in different areas can have different physical manifestations [1]. Common symptoms of cerebellar ataxia include delays in movement initiation, dysmetria, dyskinesia, dysdiadochokinea, tremor, and disturbances in motor learning[2].

The following case study describes Sam Brown, a 30-year-old man who suffered cerebellar damage following a motor vehicle accident. In the case of Mr. Brown, the damage primarily affected the midline cerebellar structures. This region is needed for balance, posture, and gait, though cerebellar injuries are seldom isolated to only one region, and Mr. Brown also experienced some motor coordination deficits more typical of lateral cerebellar lesions[2]. A case study by Chester & Reznick (1987) discusses cerebellar ataxia symptoms following severe head trauma. In their research they note that the patient had both midline and lateral cerebellar symptoms. They also discuss an ambiguity behind the anatomical cause of the patient’s cerebellar ataxia – suggesting that it could be the result of diffuse axonal injury following his traumatic brain injury, and that it may have affected multiple brain regions, particularly the superior cerebellar peduncle[3].

The goal of this case study is to paint a picture of a patient suffering from cerebellar ataxia. Ataxia is widely regarded as a physical finding and not a disease[1] and research and case studies of patients suffering from cerebellar ataxia are not abundant, for this reason it is important and interesting to explore a patient case for the specific condition.

Client Characteristics[edit | edit source]

The patient is Sam Brown, a 30-year-old retail manager, working at Staples in Kingston, Ontario. At work he has a variety of tasks including manual labour, customer relations and paperwork. Sam lives with his wife and 6-year-old son in a 3rd floor apartment (20 stairs, has an elevator). Prior to his accident Sam was able to do all activities of daily living and ambulate completely independently. Sam’s hobbies include playing in a hockey league on Saturdays and hiking with his family. Overall, Sam is healthy and active, with no co-morbidities. He is a non-smoker and social drinker (1-2 drinks/week)

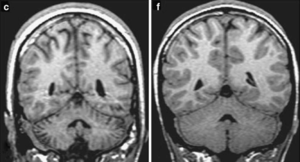

On his drive to work 18 days prior, He suffered a motor vehicle accident. In the crash he suffered from a severe concussion, whiplash and a fractured left radius. He was taken to hospital via ambulance and stayed for 5 days to be monitored and begin his rehabilitation process. While in hospital, Sam was assessed by Dr. Nancy, a neurologist who noticed Sam’s poor balance and postural control and had an MRI scan completed with him that revealed a midline/left cerebellar hemisphere lesion), as well as general cerebellar atrophy (see Figure 1)[4]. Though Dr. Nancy suspected cerebellar involvement based on Sam's symptoms, she needed to order labs (eg. thyroid function, serum B12) and run tests (initial SARA assessment - see Objective Assessment section for the physiotherapist completed SARA) to confirm her diagnosis and rule out other potential causes of Sam's symptoms[4]. This is an essential portion of Sam's early care because an accurate diagnosis is crucial to development of an effective treatment plan. Ultimately, Dr. Nancy diagnosed Sam with Truncal Cerebellar Ataxia and referred him to physiotherapy to help with his motor control symptoms.

After 5 days in hospital, Sam was discharged and referred to outpatient physiotherapy. He is not arriving at physiotherapy day 18 post-accident (day 13 post discharge) to be assessed and have a treatment plan developed.

Examination Findings[edit | edit source]

Subjective Assessment

Patient chief Concerns:

- Patient reports having some balance issues post accident; such as feeling unstable when standing unsupported, feeling unsteady and swaying while seated (but able to stay upright in sitting)

- Patient has noticed he is walking much slower than usual and he is finding it very frustrating

- Patient reported not having any falls but has had some close calls when getting out of bed

- Patient is having trouble participating in typical family activities that he use to do prior to injury such as playing with his son and going on family hikes

History of present Illness: Patient was admitted to the hospital presenting with concussion and whiplash injury due to an MVA. Upon examination by the neurologist and neuroimaging, patient was diagnosed with Truncal Cerebellar Ataxia

Past Medical History: Sam had a minor concussion 5 years ago from playing hockey. Other than that he has no history of any medical conditions. Patients reports no family history of ataxia or any cognitive conditions

Current Functional History:Patient is more dependent on his wife for daily tasks such as cooking and cleaning. He is able to shower and dress independently but has some trouble with fine motor tasks such as buttoning up his shirt or zipping up his pants (these tasks are slow and take a while for sam to complete). Sam is currently not working at his job due to the impacts of his condition. Currently he is using a quad cane at home and he reports that he is uncomfortableunstable moving around without his cane

Objective Assessment

Observation

- Posture: No visible deformities in standing and seated posture, some titubation visible when patient is seated.

- Gait Analysis: Patient has a wide base of support and presents with reduced gait speed and short stride length. Also, the patient has increased upper body/trunk movement during gait.

- Eye movement Exam:

- For the saccadic eye movement test the patient presents with slow eye movements and with some compensatory head turning movement.

- During the smooth pursuit test, the patient struggled to follow the examiners finger.

- Lastly both horizontal and vertical vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) tests were done and the patient struggled to keep his eyes on the examiner's finger.

- For all visual tests, the patient did not present with any headaches, dizziness, nausea or fogging of vision

Neurological Exam:

- Myotomes: Normal

- Dermatomes: Normal

- Deep Tendon Reflexes: Bicep, tricep, patella tendon and achilles tendons were asses and all presented with normal reflexes

- Upper and Lower Motor neuron testing: Babinski and clonus were both negative

Sensation testing

- Superficial: Sharp/dull mechanoreceptor test was performed and results were negative

- Cortical: 2 point discrimination was performed on patients on right and left forearm and palm, and patient patients sensation was normal

Range of motion and Manual Muscle Testing

| Joint Movement | ROM | MMT Grade |

|---|---|---|

| Shoulder Flexion | WNL B/L | 5 B/L |

| Shoulder Extension | WNL B/L | 5 B/L |

| Shoulder Abduction | WNL B/L | 5 B/L |

| Elbow Flexion | WNL B/L | 5 B/L |

| Elbow Extension | WNL B/L | 5 B/L |

| Wrist ROM | Not tested due to radial fracture | Not tested due to radial fracture |

| Hip flexion | WNL B/L | R:4+ L:4- |

| Hip extension | WNL B/L | R:4+ L:4- |

| Hip abduction | WNL B/L | R:4 L:4 |

| Hip Adduction | WNL B/L | R:4+ L:4- |

| Knee Flexion | WNL B/L | R:4+ L:3+ |

| Knee Extension | WNL B/L | R:4 L:3- |

| Ankle Dorsiflexion | WNL B/L | R:4+ L:3+ |

| Ankle Plantar flexion | WNL B/L | R:4 L:3 |

Outcome measures

- Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA)

- SARA was completed on May 10th and Patient scored 14/40 (see Figure 2 and 2.1)

- During the test patient mainly presented with truncal symptoms such difficulties with gait(5/8), stance (3/6) and posture (2/4)

- Patient also had some issues with the finger chase (task 5) specifically on the left side

- Berg Balance Scale (BBS)

- Patient achieved a score of 18/56 which puts him at high risk for falls.

- Patient struggled with standing unsupported with feet together (0/4), standing with eyes closed (0/4), Tandem standing (0/4) and standing on one foot (0/4)

- Time Up and Go (TUG) test

- Patient performed the TUG with his cane and achieved a time of 18.7 sec, which is associated with an increase risk of fall.

- 36- Item Short From Survey (SF-36)

- Patient scored scored 12/36

- Patient reported increased limitations of daily activities and increased physical health problems post accident. He also reported having some emotional health problems since since he has lost some independence and cannot do his regular activities. He feels like he is accomplishing less than he would like to.

Clinical Impression[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy Diagnosis

Mr.Brown was referred to Physical Therapy post MVA with a diagnosis of Truncal Cerebellar Ataxia. He is presenting with impaired balance, gait and posture as well as some motor coordination symptoms on his left side, affecting his ability to ambulate and complete activities of daily living independently. The patient is also worried abouts falls and reports having some close calls at home. Patient reports relying on his wife more for activities around this house and he is currently unable to return to work. Mr. Brown is a good candidate for Physical Therapy with the goals of improving his balance/coordination, lower limb strength and gait to be able to ambulate safely so that he can return to work and participate in regular activities with his family.

Problem List

The problem list was completed based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health[6]

| Body Structure & Function | Activity | Participation |

|---|---|---|

| Left leg weakness | Inability to complete ADLs independently | Currently unable to return to work |

| Ataxia | Reduced quality of life (SF-36 score of 12/36) | Unable to play sports and participate in regular family activities such as playing with his son and going on family hikes |

| Impaired balance (particularly in standing with reduced BOS & eyes closed) | ||

| Reduced postural control (titubation and postural sway) | ||

| Slow gait speed and reduced stride length | ||

| Dysdiadochokinesia | ||

| Dysmetria | ||

| Impaired visual reflexes and rapid eye movement |

Intervention[edit | edit source]

Short Term Goals

- Patient will improve his BBS score from 18/56 to 30/56 in 3 weeks by completing the balance exercises in the clinic with supervision and home exercise program.

- Patient will improve left leg strength to 4/5 in all joint movements in 3 weeks by completing strength exercises and walking.

Long Term Goals

- Patient will be able to ambulate safely and independently indoors in 2 months.

- Patient will be able to safely walk to the park 150m away from his apartment to play with his son in 6 weeks using a single point cane.

- Patient will be able to return to work with modified duties in 2 months.

- Patient will improve his BBS score to 42/56 in 2 months.

Supervised Exercise Program

The goal of the gait component of the program is to transition Sam from unbalanced ambulation with a quad cane to ambulating independently and safely. The physiotherapist will review education and the step through gait pattern. As Sam’s balance improves when walking, the physiotherapist will transition Sam to a single point cane and then without a mobility aid. Treadmill walking is to practise walking, and practising maintaining balance as he becomes fatigued[7]. Balance component is to improve Sam’s stability in static and dynamic environments, and decrease his fear of falling.[8] Gaze stabilization exercises were implemented to help improve balance and stability. Frenkel Exercises are designed to improve coordination for ataxic patients[9]. The main components to complete these types of exercises are concentration/attention, precision and repetition. Throughout physiotherapy treatment education on cerebellar ataxia is a priority as it is a new diagnosis for Sam.

Home Exercise Program

The home exercise program is to supplement the physiotherapy sessions, and give Sam confidence in his home environment. Exercises will be performed once per day, as tolerated. The program includes safe balance exercises, general walking practise, and trunk and lower extremity strengthening[10]. Increased trunk strength will improve balance through better trunk control.[11] Lower extremity strength included to potentially help correct asymmetrical gait, and to address any atrophy from his time spent in the hospital.

| Exercise | Parameters | Safety/Setup |

|---|---|---|

Balance

|

Reach with each hand forward, to the side, and across body just before it feels like he is unstable

10 reps each direction x 3 sets |

If wife is available she can spot him, or have another chair in front that he can grab onto |

| Walking | 10 min walking | Use single point cane until physiotherapist determines safe |

Trunk/Lower Extremity Strengthening

|

10 reps x 2 sets of each exercise | |

| Frenkel Exercises | Refer to in clinic exercise program | Only complete on days not in the clinic |

Lower Extremity

- Heel of one limb to opposite knee, sliding down crest of tibia to ankle in supine

- Sitting hip abduction and adduction both unilaterally and bilaterally

- Walk along a winding strip

Upper Extremity (in standing once mastered in sitting)

- flex/ext one elbow at a time (shoulder flexed to 90 degrees)

- flex/ext opposite elbows at the same time

- Reach and touch specific targets on the wall at arms reach

(5min upper, 5 min lower extremity)

- Walking in clinic

- Walking with head turning

- Walking with cognitive task

- Visual fixation with stationary and moving (slow and fast speed

- active eye and head movement between two targets (slow and fast)

- eyes open fixated on a moving target with head movement

Quiet standing on foam

- Progress to weight shifting

External perturbations

- In anterior posterior and lateral directions

Internal perturbations

- Reaching to move different coloured cones in all planes around the body

External perturbations 5 reps in each direction

Internal perturbations 10 reps of moving different directions

Outcome[edit | edit source]

Sam has made great improvements over the last 8 weeks in physiotherapy, and has been able to achieve most of his goals. Sam improved his SARA score by 6 points, with a recorded score of 8/14 (see figure 3 and 3.1). As the primary outcome measure for cerebellar ataxia this is a positive result. Sam made significant improvements in the gait and stance sections of the measure which were previously his biggest impairments. His gait now has increased stability, speed, cadence and step length. Sam's TUG score improved from 18.7s to 12.1s using his cane. Sam’s balance has also improved significantly as his BBS score increased by 17 points and currently scores 35/56. His improved confidence and balance has allowed him to increase his participation and confidence in IADL’s, chores, and playing with his son without the fear of falling. He now improved his left lower extremity strength, and now has 4+ strength bilaterally in hip, knee, ankle manual muscle tests. Sam can ambulate with confidence in the community with a single point cane, and without a gait aid in his apartment. It is noted Sam’s attitude has drastically changed over the last two months. Seeing continuous progress, increased in functional activities, and ability to play with his son while in physiotherapy has given him more optimism for the future. He reports not feeling like a burden at home, and now has a more positive outlook for the future. This is reflected in an increased SF-36 score of 24. Sam is ready to begin the process of returning to work on modified duties with the consultation of an occupational therapist. Sam and the physiotherapy team both agree Sam is ready to be discharged based on his progress, but would benefit with monthly appointments to progress his home exercise program if he chooses.

Mr. Reid is the occupational therapist who will be working with Sam to return him to work. Mr. Reid assessed Sam 2 weeks ago and got into contact with his employer. It was determined Sam was able to continue most of his manager duties, but will not be able to do lifting above 10lbs as it is a safety concern. Mr. Reid has assessed Sam’s workplace and helped make modifications to the work environment. Sam wants to go back to work but has concerns about managing his new diagnosis, rehab, family and work. Mr. Reid and Sam will work together to develop a stress reduction plan and implement prevention strategies and various tools. [12]

Discussion[edit | edit source]

Sam Brown, a healthy 30 year old male, was diagnosed with cerebellar ataxia after being involved in a motor vehicle accident. Following the accident Mr. Brown was taken to the hospital in stable condition where he underwent an assessment by a neurologist. Symptoms of cerebellar ataxia were identified and MRI imaging was ordered, confirming a midline/left cerebellar hemisphere lesion. Following the accident Mr. Brown spent seven days in the hospital during which he was monitored for changes to his condition, received treatment for his other injuries , and began rehabilitation. By the eighth day Mr. Brown’s healthcare team felt confident that his condition was stable and he could safely return home with his wife and son. Prior to discharge Mr. Brown worked with an occupational therapist to prepare him for his transition back home and he was referred to outpatient physiotherapy to continue his rehabilitation.

Two weeks following the accident Mr. Brown had his first appointment with the outpatient physiotherapy team. During the assessment, the SARA and SF-36 were administered, both of which have been found to be valid and reliable tools for use with ataxic patients[13][14]. The SARA is particularly helpful in quantifying the degree of impairment from cerebellar ataxia, guiding the development of a treatment plan that accurately reflects the patient's current level of impairment[15]. In the assessment, Mr. Brown presented with impaired balance, gait and posture, as well as some motor coordination symptoms of his left side. These impairments resulted in Mr. Brown having difficulty ambulating, an inability to complete ADL independently, and an overall decreased quality of life. Together with Mr. Brown, the physiotherapy team worked to develop treatment goals, all of which had a focus of returning to functional independence, increasing confidence, and allowing Mr. Brown to return to full engagement in social and work activities.

Treatment for cerebellar ataxia is focused on preventing further decline, stabilizing current symptoms, and improving functional ability[16]. Due to the wide range of impacts cerebellar ataxia can have, treatment is best delivered from a multidisciplinary team, which could include, but is not limited to, a neurologist, speech language pathologist, occupational therapist, and/or physiotherapist[17]. As treatment should be focused on maximizing safety and achieving patient goals[18], Mr. Brown’s physical therapy incorporated activities that support achievement of independent functioning such as balance training, trunk strengthening and gait training[15][18][19]. Frenkel exercises were also incorporated as they have been found to be beneficial for improving balance and gait in patients by focusing on coordination and utilizing visual feedback[20]. In addition to exercises performed in the clinic, Mr. Brown was provided a home exercise plan (HEP) to be completed independently outside of his physiotherapy appointments. HEPs, specifically balance training exercises, have been found to be beneficial in patients experiencing ataxia from cerebellar injuries[21]. In designing HEP for patients with cerebellar ataxia, the degree of challenge to balance is a important factor to consider as it, over duration or exercise frequency, has been found to be the most important factor for positive outcomes[21]. This finding highlights the importance of individualizing and continuously updating Mr. Brown’s HEP to reflect his progress.

The progress and recovery of cerebellar ataxia resulting from a traumatic brain injury (TBI) can be variable and have unique impairments that may affect the course of treatment[22]. It has been found that patients with TBI resulting in cerebellar ataxia achieve the greatest improvement six months post-injury, however improvements can continue to be achieved for years after[22]. In the case of Mr. Brown, following 8 weeks of physiotherapy treatment, he improved in all measures and had achieved a number of his rehabilitation goals. These progressions allowed him to complete an increased number of independent functional activities as well as participate in activities with his son. Although Mr. Brown still requires the use of a single point cane for ambulation in the community, he was able to progress to safe, independent walking within his home. Findings from Katz et al.[23] indicate that the achievement of independent ambulation is more favourable in patients who are younger, have lower initial TBI injury severity, and lower initial gait impairment. Based on these findings and Mr. Brown’s characteristics, with continued rehabilitation it is likely that he will be able to achieve recovery of independent ambulation within 5 months[23]. With consideration of Mr. Brown's current progress and consultation with him, the physiotherapy team assessed that he was fit for discharge, however would benefit from continued completion of his HEP. It was also agreed that Mr. Brown would have monthly appointments to update his HEP, ensuring that it continued to provide an adequate level of challenge based on his improvement.

Cerebellar ataxia resulting from a traumatic event, such as a motor vehicle accident, can be quite variable in its presentation[22] and impact many aspects of a patient's health[17]. To achieve an optimal prognosis and outcome it is therefore vital that a multidisciplinary team be utilized in order to address all areas of concern from physical to mental health[17]. For Mr. Brown’s care, the role of an occupational therapist, neurologist and physiotherapist were highlighted, however there would be many other healthcare professionals involved in his care such as a social worker or speech language pathologist. Overall the prognosis for traumatic cerebellar ataxia is very dependent on patient variables as well as the severity and location of the lesion[1]. Due to the large impact that cerebellar ataxia has on physical functioning, physiotherapy can contribute largely to more positive outcomes by both teaching compensatory strategies and restoring previous abilities[24]. Mr. Brown's personal characteristics, as well as his initial injury severity indicate that with continued engagement in rehabilitation he can expect continued improvement, facilitating his return to previous activities and level of functioning.

Self-Study Questions[edit | edit source]

Question 1 - Which of the following outcomes measures would not be appropriate for use with patients with acute cerebellar ataxia?

- Community Balance and Mobility Scale (CBMS)

- Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA)

- Function in Sitting (FIS)

- Manual Muscle Testing (MMT)

Question 2 - Which of the following are not common presentations of truncal ataxia?

- Dysmetria

- Titubation

- Reduced gait speed

- Impaired balance

Question 3 - In physical rehabilitation of cerebellar ataxia, which of the following is not typically a major focus?

- Gait retraining

- Postural control

- Motor coordination training

- Power and strength training

Answers - 1) 1; 2) 1. 3) 4.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Ashizawa T, Xia G. Ataxia. Continuum: Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 2016 Aug;22(4 Movement Disorders):1208.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Diener HC, Dichgans J. Pathophysiology of cerebellar ataxia. Movement disorders: official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 1992;7(2):95-109.

- ↑ Susan Chester C, Reznick BR. Ataxia after severe head injury: the pathological substrate. Annals of neurology. 1987 Jul;22(1):77-9.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 de Silva RN, Vallortigara J, Greenfield J, Hunt B, Giunti P, Hadjivassiliou M. Diagnosis and management of progressive ataxia in adults. Practical neurology. 2019 Jun 1;19(3):196-207.

- ↑ Potts MB, Adwanikar H, Noble-Haeusslein LJ. Models of traumatic cerebellar injury. The Cerebellum. 2009 Sep 1;8(3):211-21.

- ↑ Stucki G, Cieza A, Ewert T, Kostanjsek N, Chatterji S, Ustun TB. Application of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in clinical practice. Disability and rehabilitation. 2002 Mar 20;24(5):281-2.

- ↑ Marquer A, Barbieri G, Pérennou D. The assessment and treatment of postural disorders in cerebellar ataxia: a systematic review. Annals of physical and rehabilitation medicine. 2014 Mar 1;57(2):67-78.

- ↑ Marquer A, Barbieri G, Pérennou D. The assessment and treatment of postural disorders in cerebellar ataxia: a systematic review. Annals of physical and rehabilitation medicine. 2014 Mar 1;57(2):67-78.

- ↑ Armutlu K, Karabudak R, Nurlu G. Physiotherapy approaches in the treatment of ataxic multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair. 2001 Sep;15(3):203-11.

- ↑ Keller JL, Bastian AJ. A home balance exercise program improves walking in people with cerebellar ataxia. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair. 2014 Oct;28(8):770-8.

- ↑ Freund JE, Stetts DM. Use of trunk stabilization and locomotor training in an adult with cerebellar ataxia: a single system design. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2010 Oct 1;26(7):447-58.

- ↑ Phillips J, Drummond A, Radford K, Tyerman A. Return to work after traumatic brain injury: recording, measuring and describing occupational therapy intervention. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2010 Sep;73(9):422-30.

- ↑ Schmitz-Hubsch T, Montcel S.T. du, Baliko L, Berciano J, Boesch S, Depondt C, et al. Scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia: development of a new clinical scale. Neurology. 2006;66(11):1717–20. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000219042.60538.92

- ↑ Sanchez-Lopez C.R, Perestelo-Perez L, Escobar A, Lopez-Bastida J, Serrano-Aguilar P. Health-related quality of life in patients with spinocerebellar ataxia. Neurología (Barcelona, Spain). 2017;32(3):143–51. doi:10.1016/j.nrl.2015.09.002

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Marquer A, Barbieri G, Pérennou D. The assessment and treatment of postural disorders in cerebellar ataxia: A systematic review. Annals of physical and rehabilitation medicine. 2014;57(2):67–78. doi:10.1016/j.rehab.2014.01.002

- ↑ Pilotto F, Saxena S. Epidemiology of inherited cerebellar ataxias and challenges in clinical research. Clinical and Translational Neuroscience. 2018;2(2):2514183. doi:10.1177/2514183X18785258

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Fonteyn E.M, Keus S.H, Verstappen C.C, Schols L, Groot I.J.M. de, Warrenburg B.P.C. van de. The effectiveness of allied health care in patients with ataxia: a systematic review. Journal of neurology. 2014;261(2):251–8. doi:10.1007/s00415-013-6910-6

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Sartor-Glittenberg C, Brickner L. A multidimensional physical therapy program for individuals with cerebellar ataxia secondary to traumatic brain injury: a case series. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2014;30(2):138–48. doi:10.3109/09593985.2013.819952

- ↑ Freund J.E, Stetts D.M. Use of trunk stabilization and locomotor training in an adult with cerebellar ataxia: A single system design. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2010;26(7):447–58. doi:10.3109/09593980903532234

- ↑ Afrasiabifar A, Karami F, Najafi Doulatabad S. Comparing the effect of Cawthorne–Cooksey and Frenkel exercises on balance in patients with multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical rehabilitation. 2018;32(1):57–65. doi:10.1177/0269215517714592

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Keller J.L, Bastian A.J. A Home Balance Exercise Program Improves Walking in People With Cerebellar Ataxia. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair. 2014;28(8):770–8. doi:10.1177/1545968314522350

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Freund J.E, Stetts D.M. Continued recovery in an adult with cerebellar ataxia. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2013;29(2):150–8. doi:10.3109/09593985.2012.699605

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Katz D.I, White D.K, Alexander M.P, Klein R.B. Recovery of ambulation after traumatic brain injury. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2004;85(6):865–9. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2003.11.020

- ↑ Peri E, Panzeri D, Beretta E, Reni G, Strazzer S, Biffi E. Motor Improvement in Adolescents Affected by Ataxia Secondary to Acquired Brain Injury: A Pilot Study. BioMed research international. 2019;2019:8967138–8. doi:10.1155/2019/8967138