Bronchiectasis

Original Editors - Students from Glasgow Caledonian University's Cardiorespiratory Therapeutics Project.

Top Contributors - Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Jordan Tremblay, Remy Valiaveettil, Admin, Kate Wright, WikiSysop, Michelle Lee, Karen Wilson, Vidya Acharya, Manisha Shrestha, 127.0.0.1, Laura Ritchie and Evan Thomas

Definition[edit | edit source]

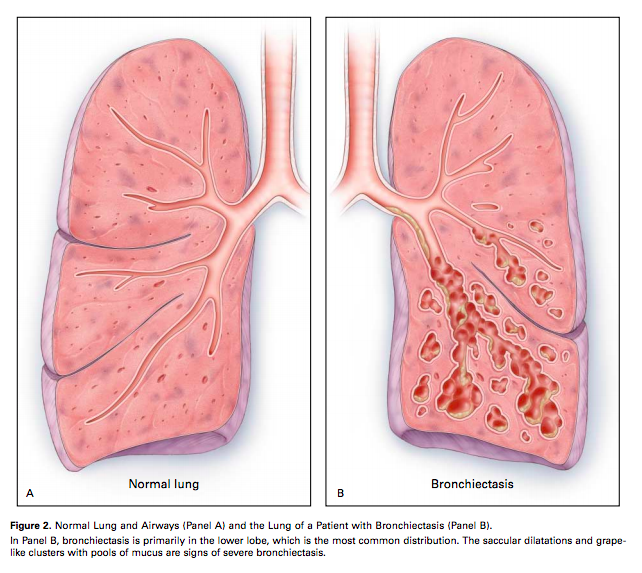

Bronchiectasis is an obstructive lung disease that results from the presence of chronic inflammatory secretions and microbes leading to the permanent dilation and distortion of airway walls, as well as recurrent infection [1].

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

Bronchiectasis is chronic irreversible dilation of the bronchi on the lungs. It follows a severe lung infection or aspiration. It is more common in conditions such as Cystic Fibrosis, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Immunodeficiency, Young's syndrome and Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis, and after chilhoos diseases such as whooping cough, TB and measles.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

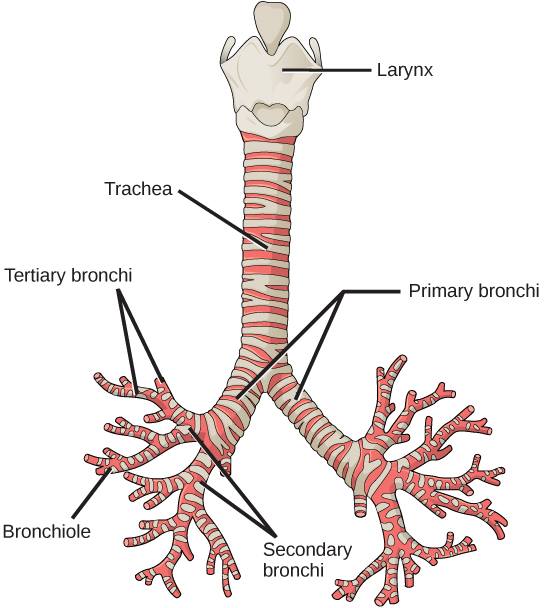

Bronchiectasis involves inflammation of the airway walls, specifically the bronchial walls [3]. The airway walls are the ‘tubes’ that run from the mouth and nose and travel to the lung. The main area that is affected in bronchiectasis is the bronchi [3]. The trachea bifurcates into the right and left main bronchi, which then further divide into secondary bronchi; one for each lobe of the lung [4]. They then divide into tertiary bronchi; one for each bronchopulmonary segment [4].

The cilia are also damaged in bronchiectasis. Cilia line the airway and are attached to the epithelium. They are hair-like with tiny hooks on the tip to grab the mucous and help move the mucous up to the throat [3].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

It is underestimated in prevalence, incidence, and morbidity because symptoms are often ascribed to smoking. A study by Hill [5]found that one in 1000 Britans have bronchiectasis, with associated deaths increasing at a rate of approximately 3% per year in England and Wales [6]. Though the overall mortality rate is increasing in these countries, rates in older groups are rising whereas rates in younger groups are falling [6]. A disproportionate amount of cases found in developing countries and in Aboriginal populations in affluent communities [7]. In some populations, an improvement in socio-economic status, housing, and education can improve overall health and reduce the incidence of respiratory infection and development of bronchiectasis [7].

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

The cause is unknown for 50% of cases, but it has been linked to inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and in 29-50% of patients, COPD [8]. There are several associated conditions with bronchiectasis including; cystic fibrosis, primary ciliary dyskinesia, lung tuberculosis, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergilosis, rheumatoid diseases, symptomatic lupus erythematosus, immune deficiency, severe childhood respiratory infection and exposure to foreign body or corrosive substance [3]. It has also been linked to an x1-antitrypsin deficiency [3]. Bronchiectasis tends to predispose patients to acquired and congenital lung infections [3].

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

The process begins with inflammatory damage to the bronchial walls, which then stimulates the formation of excess thick mucus [3]. The warm and moist environment of the lungs combines with the mucus to cause further inflammation and obstruction, creating an excellent environment for infection [3]. The thick mucus crushes the cilia and causes further damage. The immune response releases toxic inflammatory chemicals (i.e. neutrophils), as well as leads to fibrosis and bronchospasm if persistent[3].

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Currently, a high-resolution CT scan is the gold standard for diagnosis of bronchiectasis [3]. Parallel tramlines and ring shadows may be present on the scan, indicating thickened airway walls and dilated airways, respectively[3]. There may also be ‘glove finger shadows’, which are finger –like projections that represent the dilated bronchi filled with solidified secretions[3].

Spirometry will simply identify if there is an airway obstruction, but this can be indicative of many other diseases[3].

Microbiology can also be used to identify the bacteria present during an exacerbation [3]. A sputum sample is sent off and the results are returned with the incidence of bacterial colonization measured [3].

Clinical Manifestations[edit | edit source]

As delicate cilia are often damaged due to the presence of thick mucus, the voluminous quantities of sputum formed cannot be efficiently cleared[3]. These secretions will lead to the production of wheezes, coarse crackles and squeaks on auscultation. Often times, patients will also present with muscular dysfunction due to inflammation, gas exchange abnormalities, inactivity, malnutrition, hypoxia and medications [9]. Dyspnoea on exertion seems to be a major clinical manifestation as it is experienced by three out of four patients. Other physical manifestations include chest pain, snoring, finger clubbing, fatigue, persistent cough, recurrent infection, and loss of appetite[3]. Stress incontinence can also be a result of excess coughing. Bronchiectasis tends to also have psychological manifestations, such as anxiety, depression, reduced confidence, altered relationships and time off work[3].

Exacerbations can occur several times a year and are identified by four or more of the following signs and/or symptoms: change in sputum, increased dyspnoea, increased cough, fever of greater than 38°, increased wheeze, decreased exercise tolerance, fatigue, lethargy, and radiographic signs of a new infection[3].

Physiotherapy and Other Management[edit | edit source]

The key to management of bronchiectasis is through education and systemic management. Currently, antibiotics are used at the first sign of change in sputum colour[3]. Since antibiotics do not help with the persistent inflammation in the airways, inhaled steroids are taken as an anti-inflammatory and to decrease sputum production[3]. Brochodilators tend to help, as well as increased levels of vitamin D, which most patients are deficient in[3].

Physiotherapy has a very valuable role in aiding with symptoms of bronchiectasis. Since mucociliary clearance is reduced to about 15% of normal, patients tend to cough more[3]. With treatment, patients are discouraged from coughing unless they are ready to expectorate. This is accompanied by a daily chest clearance program in order to eliminate coughing between sessions. Hydration, exercise and AD/ACBT treatments have been shown to be quite effective as well[3]. Pelvic floor exercises may also be required in order to control the stress incontinence experienced with bronchiectasis[3].

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

In order to assess the effectiveness of treatment and changes in quality of life, patients can complete a St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) [3]. The SGRQ is a commonly used questionnaire to measures health related quality of life in patients with respiratory conditions [10].

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Barker AF. Bronchiectasis. New England Journal of Medicine 2002; 346: 1383-93.

- ↑ salamhossein. Bronchiectasis Animation - What is Bronchiectasis? Video.mp4. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uNeprw1rsgE [last accessed 18/5/15]

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 3.24 3.25 Hough A. Physiotherapy in Respiratory and Cardiac Care: an evidence-based approach. 4th ed. Hampshire: Cengage Learning EMEA, 2014.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Palastanga N, Soames R. Anatomy and human movement: structure and function. 6th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2012.

- ↑ Hill AT, Welham S, Reid K, Bucknall CE. British Thoracic Society national bronchiectasis audit 2010 and 2011. Thorax 2012; 1:1-3.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Roberts HJ, Hubbard R. Trends in bronchiectasis mortality in England and Wales. Respiratory Medicine 2010; 104: 981-5.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Chang AB, Marsh RL, Vaughan-Smith HC, Hoffman LR. Emerging drugs for bronchiectasis. Informa healthcare 2012; 17: 361-378.

- ↑ Goeminne P, Dupont L. Non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: Diagnosis and management in the 21st century. Postgrad Med J 2010; 86: 493-501.

- ↑ Ozalp O, Inal-Ince D, Calik E, Vardar-Yagli N, Saglam M, Savci S, et al. Extrapulmonary features of bronchiectasis: muscle function, exercise capacity, fatigue, and health status. Multidisciplinary Respiratory Medicine 2012; 7: 1-6.

- ↑ Ferrer M, Miravitlles M, Villasante C, Alonso J, Sobradillo V, Gabriel R, et al. Interpretation of quality of life scores from the St George's Respiratory Questionnaire. Eur Respir J 2002;19(3):405-13.