Antiretrovirals and HIV

Original Editor - Vidya Acharya

Top Contributors - Vidya Acharya, Melissa Coetsee, Kim Jackson and Carina Therese Magtibay

Introduction[edit | edit source]

HIV is a major global public health issue, claiming 36.3 million [27.2–47.8 million] lives so far, but has become a manageable chronic health condition, enabling people living with HIV to lead long and healthy lives[1], which is possible due to an increase in access to effective HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and care. According to UNAIDS, 37.7 million [30.2 million–45.1 million] people were globally living with HIV in 2020. As of 30 June 2021, 28.2 million people had access to antiretroviral therapy; the number has increased from 7.8 million [6.9 million–7.9 million] in 2010.[2]

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is the treatment recommended by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the World Health Organization (WHO) for treating all patients with HIV.[3] The treatment does not offer a cure for the disease but provides longer lives and reduces transmission. The drop in the spread of the disease has resulted in wide acceptance of the therapy by HIV-positive individuals. FDA approved the first medicine nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor zidovudine in 1987. And research in the next decade showed that combining HIV medicines to be effective in treating patients[3].

An HIV regime is this daily treatment of multiple HIV medications, including three HIV medications from a minimum of two drug classes. Studies show that 3-drug therapy reduces the rate of AIDS, hospitalization, and death by 60% to 80%. The success of ART therapy has reduced HIV to a chronic condition in many parts of the world. CDC plans to implement a 90-90-90 plan by 2030. (90% HIV diagnosed, 90% on therapy, and 90% suppressed)[3].

Goals of Antiretroviral Therapy[edit | edit source]

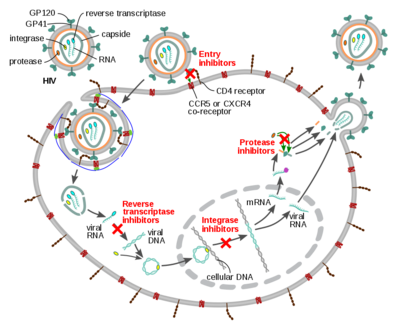

HIV produces new copies of itself inside an infected cell, which can then infect other healthy cells within the body. The more cells HIV infects, the greater its impact on the immune system (immunodeficiency). Antiretroviral medicines slow down replication by interfering with its replication process in different ways and, thus, the spread of the virus within the body.[2]

The key goals of antiretroviral therapy are to[4]:

- to prevent HIV from multiplying

- achieve and maintain suppression of plasma viremia to below the current assays’ level of detection;

- improve overall immune function as demonstrated by increases in CD4+ T cell count;

- prolong survival;

- reduce HIV associated morbidity;

- improve overall quality of life; and

- reduce risk of transmission of HIV to others

It is important to remember that current antiretroviral regimens do not eradicate HIV; viral rebound occurs rapidly after treatment discontinuation, followed by CD4 decline, with potential for disease progression. It is essential to strictly follow the prescribed regimen to avoid viral rebound and the potential for selection of drug resistance mutation. A combination regimen should consist of preferably 3 (but at least 2) active agents based on genotype resistance test results.[4]

Antiretroviral Drugs[edit | edit source]

There are classes of drugs used in antiretroviral therapy[3]:

- Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI): HIV needs an enzyme called reverse transcriptase to generate new copies of itself. This group of medicines inhibits reverse transcriptase by preventing the process that replicates the virus’s genetic material. Names of FDA approved drugs: Abacavir, emtricitabine, lamivudine; Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, zidovudine

- Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI): this group of medicines also interferes with the replication of HIV by binding to the reverse transcriptase enzyme itself. Though NNRTIs do not get incorporated into the viral DNA, they inhibit the movement of protein domains of reverse transcriptase that are essential to carry out the DNA synthesis and stops the production of new virus particles in the infected cells. Name of FDA approved drugs-Efavirenz, etravirine, nevirapine, rilpivirine

- Protease inhibitors (PI): protease is a digestive enzyme that is needed in the replication of HIV to generate new virus particles. It breaks down proteins and enzymes in the infected cells, which can then go on to infect other cells. The protease inhibitors prevent this breakdown of proteins and therefore slows down the production of new virus particles. Name of FDA approved drugs: Atazanavir, darunavir, fosamprenavir, ritonavir, saquinavir, tipranavir

- Integrase inhibitor (II): Block the action of integrase, preventing the viral genome from inserting itself into the DNA of a host cell. Name of FDA approved drugs

- Chemokine Receptor Antagonist (CCR5 antagonists): block CCR5 coreceptors on the surface of certain immune cells that HIV needs to enter the cells.[5]Name: Maraviroc.[6]

- Fusion Inhibitor: Fusion inhibitors block HIV from entering the CD4 T lymphocyte (CD4 cells) of the immune system. Enfuvirtide.[5]

- Integrase Inhibitors: Block the action of integrase, preventing the viral genome from inserting itself into the DNA of a host cell.[3]

- Post-Attachment Inhibitors: This class is a monoclonal antibody that binds CD4 inhibiting viral entry into the cell.[3]

- Pharmacokinetic Enhancers: Inhibition of human CYP3A protein, increasing plasma concentration of other anti-HIV drugs.[3]

Indication[edit | edit source]

Antiretroviral therapy should be started as soon as possible for:[3]

- People who are at a risk of transmission after being exposed to HIV-positive infectious bodily fluids through skin puncture, damaged skin, or direct mucous membrane contact. The United States Public Health Service guidelines recommend starting prophylactics up to 72 hours post-exposure. The recommended regimen is emtricitabine plus tenofovir plus raltegravir for four weeks. A follow-up HIV testing at 6, 12, and 24 weeks should be done and if the test results are negative at 24 weeks, then they are considered not infectious.

- A recent HIV infection is one that occurs up to 6 months after infection.

- Pregnant women should begin treatment immediately to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV and protect the woman's health.

Before initiating the therapy, physician and patient must balance the virological and immunological benefits of early treatment need to be balanced with the costs of drug therapy, the risk of drug side effects, and the risk of drug resistance if adherence is suboptimal, and potential drug interactions with the patient's current medications[7].

Adverse Effects[edit | edit source]

Adverse Events associated with Antiretroviral therapy are[8]:

- Bone mineral density

- Bone Marrow Suppression

- Dyslipidemia

- Nausea and diarrhea

- Jaundice

- Swelling, erythema, hematoma

- Myopathy/Elevated Creatine Phosphokinase

- Some long-term adverse effects of HIV medicines are hepatotoxicity, kidney failure, heart disease, diabetes/insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, osteoporosis, suicidal ideation/depression, and nervous system deficits.[3]

These adverse effects may require supportive treatment, monitoring, and adjustment of the HIV regimen.

Implications for Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Mortality and morbidity have significantly declined with the availability of ART. It has reduced health service utilization and improved the quality of life among persons living with HIV. [9]However, the impact of living with HIV infection over many years, coupled with antiretroviral toxicities, has created a complex pattern of healthcare needs and recorded a high incidence of comorbidities in people living with HIV (PLWH). This high rate of metabolic abnormalities seen from toxic side effects of antiretroviral therapy includes low bone mineral density (BMD), sarcopenia[10], frailty, falls, consequent increased risk of fracture, cardiovascular diseases, and instability of fat metabolism, which can be addressed by physical rehabilitation.[11] According to the study done in sub-Saharan Africa countries, physiotherapists should be more aware of the potential risk of falls and bone demineralization among PLWH and routine assessments should be carried out to detect fall risk in the older and younger PLWH.[12]

Research studies show that physical exercise (aerobic and resistance exercises) improves lean body mass, cardiovascular fitness[13], strength, changes mood state, increases BMD, reduces fracture risk, and invariably enhances the quality of life (QoL) in PLWHA supporting the role of physical exercise as a complementary alternative therapy in the management of chronic illnesses in PLWHA. [11]

See the the following pages for physiotherapy management:

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ World Health Organisation.HIV/AIDS Factsheet Accessed on 12/2/22

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 UNAIDS. Global HIV & AIDS statistics — Fact sheet. Accessed on 12/02/22

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Kemnic TR, Gulick PG. HIV antiretroviral therapy. StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Jun 23.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Pau AK, George JM. Antiretroviral therapy: current drugs. Infectious Disease Clinics. 2014 Sep 1;28(3):371-402.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 HIVinfo.NIH. HIV Overview. FDA-Approved HIV Medicineshttps://hivinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv/fact-sheets/fda-approved-hiv-medicines Accessed on 12/2/22

- ↑ Eggleton JS, Nagalli S. Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART). 2021 Apr 7. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2021.

- ↑ Shafer RW, Vuitton DA. Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) for the treatment of infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy. 1999 Mar 1;53(2):73-86.

- ↑ Clinical Info HIV.org. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents Living with HIV Accessed on 14/02/22

- ↑ Banda GT. Common impairments and functional limitations of HIV sequelae that require physiotherapy rehabilitation in the medical wards at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Malawi: A cross sectional study. Malawi Medical Journal. 2019 Sep 3;31(3):171-6.

- ↑ Bonato M, Turrini F, Galli L, Banfi G, Cinque P. The role of physical activity for the management of sarcopenia in people living with HIV. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020 Jan;17(4):1283.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Ibeneme SC, Irem FO, Iloanusi NI, Ezuma AD, Ezenwankwo FE, Okere PC, Nnamani AO, Ezeofor SN, Dim NR, Fortwengel G. Impact of physical exercises on immune function, bone mineral density, and quality of life in people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC infectious diseases. 2019 Dec;19(1):1-8.

- ↑ Charumbira MY, Berner K, Louw Q. Physiotherapists’ awareness of risk of bone demineralisation and falls in people living with HIV: a qualitative study. BMC health services research. 2021 Dec;21(1):1-9.

- ↑ O'Brien K, Nixon S, Tynan AM, Glazier R. Aerobic exercise interventions for adults living with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010(8).